Chapter 17 Drugs Affecting Uterine Motility

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| COMT | Catechol-O-methyl transferase |

| COX | Cyclooxygenase |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| IV | Intravenous |

| MLC | Myosin light-chain |

| MLCK | Myosin light-chain kinase |

| MLCP | Myosin light-chain phosphatase |

| NO | Nitric oxide |

| NSAID | Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug |

| OT | Oxytocin |

| PG | Prostaglandin |

Therapeutic Overview

There are three clinical uses for uterine stimulants:

during pregnancy can significantly alter uterine responses. This may occur through alterations in receptor density, coupling to effector mechanisms, or other processes.

In general there are four groups of compounds used clinically to stimulate uterine motility. The most potent and specific is oxytocin (OT), which is commonly used to induce or augment labor in late gestation. It is much less useful in early gestation, however, because the uterus responds poorly to OT. The second group consists of the prostaglandins (PGs) of the E or F families. Because the uterus is always responsive to PGs, they can stimulate contractions at any stage of gestation (see Chapter 15). The PGs are used in combination with mifepristone to induce early abortion. They are also commonly used in late gestation and can ripen the cervix and cause myometrial contraction. The third group is the ergot alkaloids (see Chapter 36). These compounds cause intense tonic myometrial contractions, which are undesirable for stimulating labor but are useful for treating postpartum hemorrhage. They are, however, rapidly being replaced by analogs of OT or PGs. The final group is the progesterone receptor antagonists, of which mifepristone is the most widely used (see Chapter 40). These are particularly useful for termination of early pregnancy, when uterine quiescence is dependent principally on progesterone. They have also recently been used to induce labor in late gestation.

There are four clinical uses for uterine relaxants:

Because there is no evidence clearly supporting the superiority of any one tocolytic, their use varies markedly. Magnesium sulfate is used most frequently as a tocolytic agent despite the lack of evidence of effectiveness from well-designed trials. Adrenergic β2 receptor agonists (see Chapter 11), usually ritodrine or terbutaline, have often been prescribed, but their use is declining because of maternal side effects. The nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and PG synthesis inhibitors (see Chapter 36) have also been used, although there are concerns about potential adverse effects on the fetus. Similarly, calcium channel blockers (principally nifedipine) are used increasingly, but their efficacy has not been proven. The more recently developed OT antagonist, atosiban, has demonstrated efficacy but may be associated with fetal adverse effects and has not been approved for use as a tocolytic in the United States. Limited research supports the use of nitroglycerin as a nitric oxide (NO) donor to enhance uterine quiescence, and there has been a resurgence of interest in the use of progesterone supplementation in early pregnancy to prevent preterm labor in women at high risk.

Dysmenorrhea is caused by uterine spasms secondary to the release of PGs at the time of endometrial breakdown associated with menstruation. Several NSAIDs relieve the discomfort associated with uterine cramps around the time of menstruation (see Chapter 36).

Mechanisms of Action

| Therapeutic Overview | |

|---|---|

| Uterine Stimulation | Uterine Relaxation |

| Pregnancy termination | Arrest of preterm labor |

| Cervical ripening | Facilitation of intrauterine manipulation |

| Induction of labor | Reversal of pharmacological uterine hyperstimulation |

| Augmentation of labor | Relief of dysmenorrhea |

| Postpartum uterine atony | |

pharmacological characteristics change constantly in response to changes in estrogen and progesterone throughout the menstrual cycle and more so during pregnancy. Most unique are the massive anatomical and physiological changes that transform it during pregnancy. Not surprisingly, the factors regulating uterine contractility, and the effectiveness of drug therapy, change remarkably during the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and particularly around parturition.

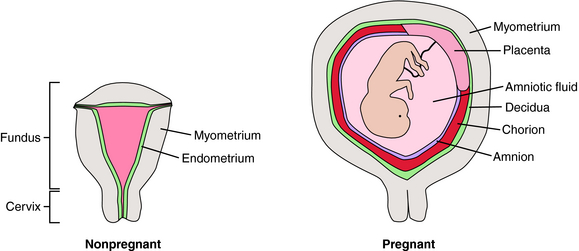

At first glance, the uterus appears anatomically simple (Fig. 17-1). There is a body (fundus) and an outflow tract (cervix) through which the fetus and placenta must pass during parturition. The fundus is composed principally of smooth muscle (myometrium) surrounding the uterine cavity, which is lined with a specialized endometrium containing stromal cells and glandular epithelium. During pregnancy the myometrium undergoes massive hypertrophy and hyperplasia, predominantly under the influence of estrogen. The endometrium is also a target for estrogen and progesterone, changing dramatically throughout the menstrual cycle. In pregnancy, stromal cells enlarge, whereas glandular epithelial cells become less prominent. The pregnant endometrium is termed the decidua. As pregnancy progresses, the fetus grows in a gestational sac composed of two types of fetal tissue—the inner amnion, a single layer of cuboidal epithelial cells with a loose connective tissue matrix, and the outer chorion, which is a continuation of the placental trophoblast that extends from the edge of the placenta and surrounds the entire developing conceptus. As the fetus grows, the amniochorial layer becomes fused with the maternal decidua. Near the time of parturition, the decidua is invaded by cells of the immune system. The timing of parturition is a complex and coordinated event involving fetal tissues as well as the maternal decidua, myometrium, and immune system. It appears that there are several redundant pathways for initiation of labor.

It is important not to view labor simply as the onset of myometrial contractions. For successful parturition, the cervix must also undergo dramatic changes, called ripening. In this process collagen and glycosaminoglycans of the cervix are broken down, and the content of H2O and hyaluronic acid increases, probably as a consequence of the action of matrix metalloproteinases. As a result, the cervix is transformed from a rigid structure that keeps the products of conception confined to the uterus into a soft and pliable structure. During ripening the cervix becomes thin (effacement) and then begins to open (dilation). Active labor contractions ensue to continue the process of dilating the cervix and pushing the fetus through the maternal pelvis. These processes must be well coordinated to ensure normal progressive labor.

Regulation of Myometrial Contractility

Although the processes regulating the myometrium and other smooth muscles are similar in some respects (see Chapters 9, 19 and 24), there are unique aspects in the control of the myometrium that determine its responsiveness to drugs. Much of our understanding of this process is derived from animal models, particularly sheep. In this species the signal for parturition is mediated through the fetus. In the days preceding the onset of labor, the fetal adrenal increases the secretion of cortisol; the resulting increase in fetal serum cortisol induces the synthesis of placental 17-hydroxylase, which catalyzes conversion of placental progesterone to estrogen. The consequential large increase in the maternal serum estrogen/progesterone ratio stimulates increased uterine contractility and labor onset. In most species this “progesterone withdrawal” is thought to be a critical step in transformation of the uterus from its quiescent state during pregnancy into an active state during parturition.

The actions of estrogen and progesterone on the uterus are not well understood. As in other tissues (see Chapter 40), expression of some uterine genes may be increased, whereas others are decreased through interactions with nuclear receptors. The reproductive effects of estrogen appear to use estrogen receptor α, whereas effects of progesterone are mediated primarily through the progesterone receptor B isoform (see Chapter 40). In human pregnancy it has been speculated that a progesterone withdrawal may be caused by increased expression of the progesterone receptor A isoform, which may counteract the effects of progesterone receptor B activation.

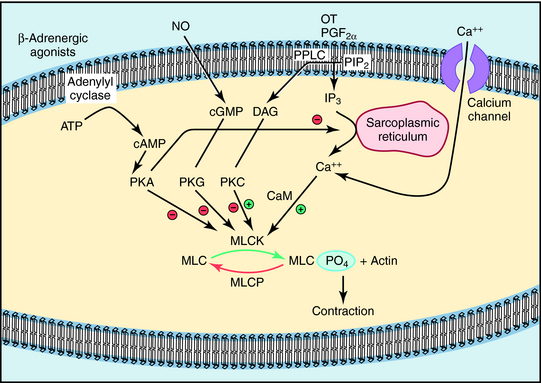

The molecular mechanism that underlies myometrial contraction is similar in most respects to that of other smooth muscle (see Chapter 24). The final focal point of the contractile response is the interaction of phosphorylated myosin light chains (MLCs) with actin. Phosphorylation of MLCs is regulated by the balance of activity between MLC kinase (MLCK) and MLC phosphatase (MLCP), which is regulated by Ca++-calmodulin (Fig. 17-2). The most important uterine stimulants (OT and PGF2α) activate specific G-protein coupled membrane receptors that activate Gq and membrane phospholipase C (see Chapter 1), leading to the release of Ca++ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum and the influx of Ca++ through L-type Ca++ channels. The resultant increase in intracellular Ca++ increases MLCK activity and uterine contraction.

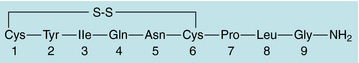

The most potent and specific uterine stimulant is OT (Fig. 17-3). This nonapeptide hormone is synthesized in the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary. It has been used for many decades to stimulate uterine contractions, which are indistinguishable from normal labor. However, its role in the physiological regulation of parturition is not yet completely clear. There is a marked increase in the concentration of OT receptors in the uterus at the time of parturition, suggesting that OT plays an important functional role in mediating this event.

The other major uterine stimulants are the PGs, principally PGE2 and PGF2α (see Chapter 15). The rate of intrauterine synthesis of PGs increases several-fold at parturition; however, the role of this process in normal labor is controversial. Because PGs are known to stimulate uterine activity at any time during gestation, they are effective abortifacients (see Chapter 15). PGE2 also appears to be important in stimulating processes that result in ripening of the cervix.

The mechanism of action of the ergot alkaloids in the uterus is unclear. Most evidence suggests their contractile effects are mediated by interaction with α1 adrenergic receptors (see Chapter 11), but they also bind to serotonin and dopamine receptors. The use of these drugs is rapidly being replaced by OT or PG agonists.

The finding that administration of progesterone receptor antagonists during pregnancy caused cervical ripening and uterine contractions supports a role for progesterone in the maintenance of uterine quiescence. The molecular mechanisms are poorly understood but may involve remodeling of the cervical extracellular matrix. For example, mifepristone decreases cervical tensile strength through a mechanism that involves up regulation of matrix metalloproteinase type 2.

As in many other smooth muscles, β2 receptor stimulation causes relaxation (see Chapters 11, Chapter 16 and Chapter 24), an effect mediated by activation of adenylyl cyclase and inhibition of MLCK activity (see Fig. 17-2). NSAIDs inhibit PG synthesis by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX, see Chapter 15 and Chapter 36). Both COX-1 and COX-2 catalyze PG generation in the pregnant uterus, but the increased PG generation noted at parturition appears to result predominantly from increased COX-2. However, selective inhibition of COX-2 is associated with an increased incidence of unwanted side effects (see Chapter 36). Although magnesium sulfate is a commonly used tocolytic drug in North America, its mechanism of action is unclear but may be related to its actions as a divalent cation to compete with Ca++ in myometrial cells. In addition, recent studies indicate that magnesium sulfate may act as an antiinflammatory agent during preterm labor.

Calcium channel blockers (nifedipine and nicardipine) inhibit uterine contractions because of their ability to suppress intracellular Ca++ levels by limiting Ca++ influx through L-type Ca++ channels in smooth muscle cells, promoting Ca++ efflux from cells and inhibiting the release of Ca++ from sarcoplasmic reticulum (see Chapters 20 and 22). A meta-analysis of nine randomized trials (679 patients) specifically comparing treatment of premature labor with nifedipine versus β2 receptor agonists (terbutaline or ritodrine) demonstrated that nifedipine was more effective than the β2 receptor agonists in delaying delivery for at least 48 hours. Although early animal studies showed that Ca++ channel blockers produce metabolic acidosis in the fetus, they are increasingly used as tocolytic agents.

Pharmacokinetics

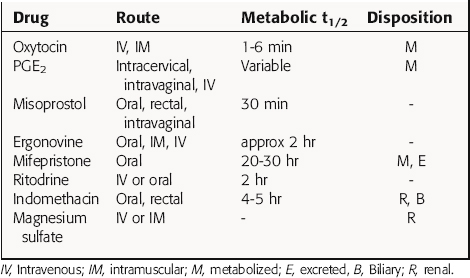

Regardless of whether these compounds are given to stimulate or relax the pregnant uterus, most will cross the placenta and may have adverse effects on the fetus. Many agents affect fetal cardiovascular function, which renders fetal heart rate-based monitoring methods invalid, subsequently requiring special vigilance to avoid detrimental outcomes for either the mother or the fetus. Pharmacokinetic parameters of selected drugs are summarized in Table 17-1.

The antiprogestin mifepristone is increasingly used for early (<8 weeks gestation) termination of pregnancy. It is most effective when used in concert with a PG analog (usually misoprostol). This combination treatment actually increases the efficiency of induction of contractions compared with PG analogs used alone.

Ritodrine was the first β2 receptor agonist approved for use as a tocolytic agent in late pregnancy. To arrest active labor, it is administered by an IV infusion pump, with the dose carefully titrated to uterine activity. The infusion must be increased slowly and maternal and fetal cardiovascular and metabolic parameters monitored carefully to avert the predictable side effects of these agents. Terbutaline and other β2 receptor agonists have also been used as tocolytics (see Chapter 11). These drugs often lose their effectiveness as a result of tachyphylaxis. Although oral forms of these agents have been used for prophylaxis, the best evidence indicates they are not effective when administered by this route.

Results of early studies indicated that birth could be delayed for 48 hours through use of the NSAIDs. However, the prototype drug indomethacin caused constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus (see Chapter 15) because PGE2 is necessary to maintain ductal patency, thus reducing their use. However, there has been a recent resurgence in the use of indomethacin by rectal suppository, often followed by oral maintenance therapy. Recent trials have evaluated intravenous infusions of selective COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib. Celecoxib maintains uterine quiescence without the constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus.

Relationship of Mechanisms of Action to Clinical Response

Painful menstruation is very expensive in terms of productivity and quality of life. The most common form of dysmenorrhea is primary dysmenorrhea, consisting of uterine spasm without underlying pathology. The spasm results from the release of PGs from degenerating endometrial cells. NSAIDs have been extremely effective in preventing or ameliorating this condition (see Chapter 15 and Chapter 36). They are generally administered a few hours before expected menstruation or at the first sign of bleeding and are taken 1 to 2 days thereafter. An alternative approach is to use oral contraceptives to inhibit ovulation, reducing the synthesis of PGs in the endometrium; this results in less uterine spasm during menstruation. Because primary dysmenorrhea is caused by excessive uterine muscle contractions, agents that block uterine contractility (i.e., tocolytics) may be effective in its treatment. NO, nitroglycerin, and Ca++ channel blockers all have tocolytic effects and are under investigation as potential therapies of dysmenorrhea.

Pharmacovigilance: Side Effects, Clinical Problems, and Toxicity

Clinical problems are summarized in the Clinical Problems Box.

The major side effect of uterine stimulants is hyperstimulation. This is usually easy to recognize by the appearance of frequent (<2 minute interval) contractions or of a prolonged tetanic contraction usually accompanied by maternal pain and often fetal bradycardia. Hyperstimulation produced by OT administered IV is easily reversed by reducing the infusion rate or discontinuing the drug. Because OT has a short half-life, normal uterine tone returns within a few minutes. Hyperstimulation resulting from PG gel insertion into the cervix or vagina may be a greater problem, but in severe cases saline can be used to wash out the PG. If there is no reduction in tone or continued fetal bradycardia, it may be necessary to administer β2 receptor agonists IV. In rare instances emergency cesarean section may be necessary. Induction of labor should be performed only when necessary, and always in settings with adequate facilities.

PGE2 preparations for cervical ripening may be associated with an increased incidence of uterine rupture during labor in women who have had a previous cesarean section. Other side effects of PG preparations include gastrointestinal and pulmonary problems (see Chapter 15). However, these result very infrequently from local application of a PG gel.

Concern has been raised about the use of indomethacin to arrest preterm labor because of the adverse effect this may have on constriction of the fetal ductus arteriosus (see Chapter 15). Although this effect may be greater in term fetuses, it can be seen throughout the third trimester. Fetal renal toxicity is also frequent and commonly manifests as a reduction in fetal urine output, resulting in reduced amniotic fluid volume (oligohydramnios). It is not clear whether these disturbances are associated with adverse fetal outcomes, but this is a serious concern in light of increasing evidence regarding the fetal origins of adult disease. Also, findings from retrospective studies have shown that there is an increased incidence of intracranial hemorrhage, patent ductus arteriosus, and necrotizing enterocolitis in neonates receiving indomethacin, although some patients were treated with higher doses for longer periods than currently recommended. Prospective randomized trials are clearly required to evaluate the risk-benefit ratios of NSAIDs for arresting preterm labor.

There is much controversy about tocolytic drugs, particularly concerning their effectiveness and cost/benefit ratio. Many clinical studies have not included a placebo control group, limiting their conclusions without knowledge of potential placebo effects. Although most trials measure prolongation of pregnancy as the primary outcome, the important outcome is the eventual health of the newborn and the mother. In addition, there is no consensus as to the criteria used to exclude treatment in clinical trials. In addition, although there is a consensus that administration of glucocorticoids to the mother for 24 to 48 hours before birth will accelerate fetal pulmonary maturation and reduce the incidence of neonatal respiratory distress syndrome, randomized, placebo-controlled studies have not shown that use of tocolytic drugs increases the chance of completing a course of glucocorticoid therapy. Further, the extensive use of artificial surfactant treatment in preterm neonates may reduce the benefit of glucocorticoids administered in utero. Finally, in most regions of the United States and Canada, tocolytic therapy is the standard of care in preterm labor. Thus the medico-legal climate often dictates that some form of tocolytic therapy be attempted, despite the lack of strong supportive evidence.

| Uterine Stimulants | Maternal | Fetal |

| Oxytocin | Uterine hypertonus, rupture, hypotension, H2O intoxication | Hypoxia |

| Prostaglandins | Uterine hypertonus, rupture, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, bronchospasm | Hypoxia |

| Mifepristone | None | None |

| Uterine Relaxants | Maternal | Fetal |

| Adrenergic β2 receptor agonists | Hypotension, tachycardia, palpitations, dysrhythmias, pulmonary edema, hyperglycemia, hypokalemia | Tachycardia |

| Hyperglycemia | ||

| NSAIDs | Gastrointestinal bleeding, nausea, headaches, myelosuppression | Constriction of ductus arteriosus, oligohydramnios |

| Magnesium sulfate | Skin flushing, palpitations, headaches, depressed reflexes, respiratory depression, impaired cardiac conduction | Muscle relaxation, central nervous system depression (rare) |

| Progesterone | None | None |

New Horizons

The search for novel agents to promote uterine quiescence in the treatment of preterm labor continues to focus on PGs, although relaxation of muscle contractions by agents that act through guanylyl cyclase are also being investigated. New PG receptor antagonists with specificity for the PGF2α receptor are effective in inducing uterine quiescence in animal models, but effects in humans have not yet been examined. The effects of NO in animals include relaxation of the uterus, similar to effects on other smooth muscles (see Chapter 24). Sildenafil has shown promise in reducing uterine contractility in animal models. However, recent studies indicate that contraction of uterine smooth muscle, unlike vascular smooth muscle, may not depend on the guanylyl cyclase system.

Belfort et al. 2003 Belfort MA, Anthony J, Saade GR, Allen JCJr, Nimodipine Study Group. A comparison of magnesium sulfate and nimodipine for the prevention of eclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:304-311.

Cole et al. 2004 Cole S, Smith R, Giles W. Tocolysis: Current controversies, future directions. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2004;5:424-429.

Olson DM, Ammann C. Role of the prostaglandins in labour and prostaglandin receptor inhibitors in the prevention of preterm labour. Front Biosci. 2007;12:1329-1343.

Word et al. 2007 Word RA, Li XH, Hnat M, Carrick K. Dynamics of cervical remodeling during pregnancy and parturition: Mechanisms and current concepts. Semin Reprod Med. 2007;25:69-79.

Wray S. Insights into the uterus. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:621-631.