17

Drug Reactions

• The skin is one of the most common targets for adverse drug reactions.

• Adverse cutaneous drug reactions (ACDR) affect 2–3% of all hospitalized patients.

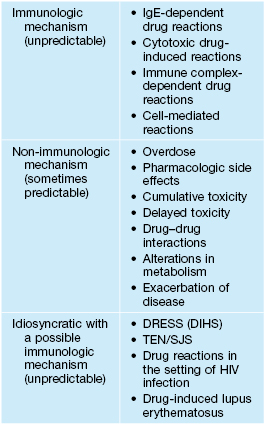

• Pathogenesis of ACDR not totally understood but can involve immunologic, nonimmunologic, and idiosyncratic mechanisms (Table 17.1).

Table 17.1

Mechanisms of cutaneous drug-induced reactions.

DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (also known as DIHS, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome); SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

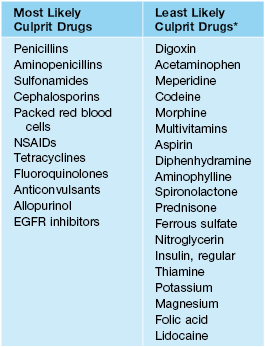

• Some of the most and least likely culprit drugs are listed in Table 17.2.

Table 17.2

Selected most and least likely drugs to cause adverse cutaneous drug reactions.

* With the exception of urticaria with narcotics and aspirin.

NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Adapted from: Arndt KA, Jick H. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1976;235:918–923.

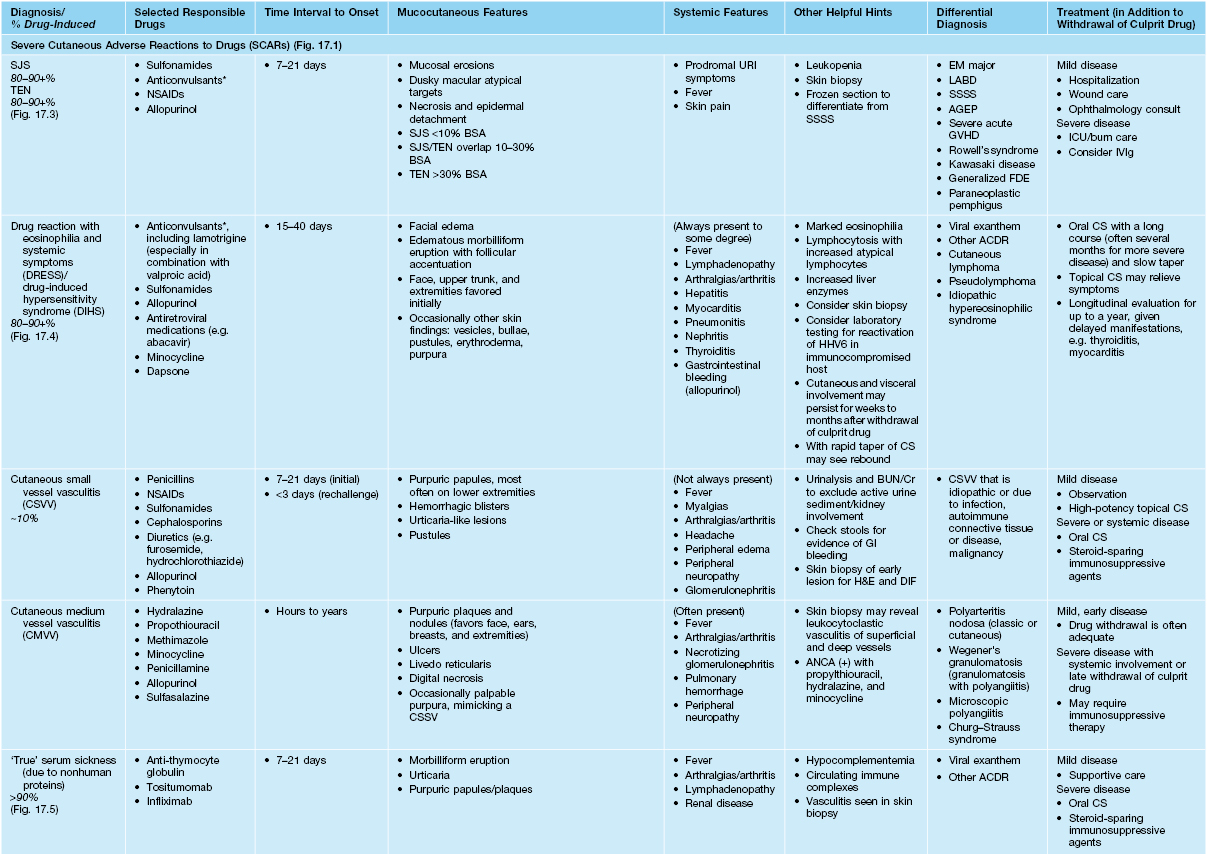

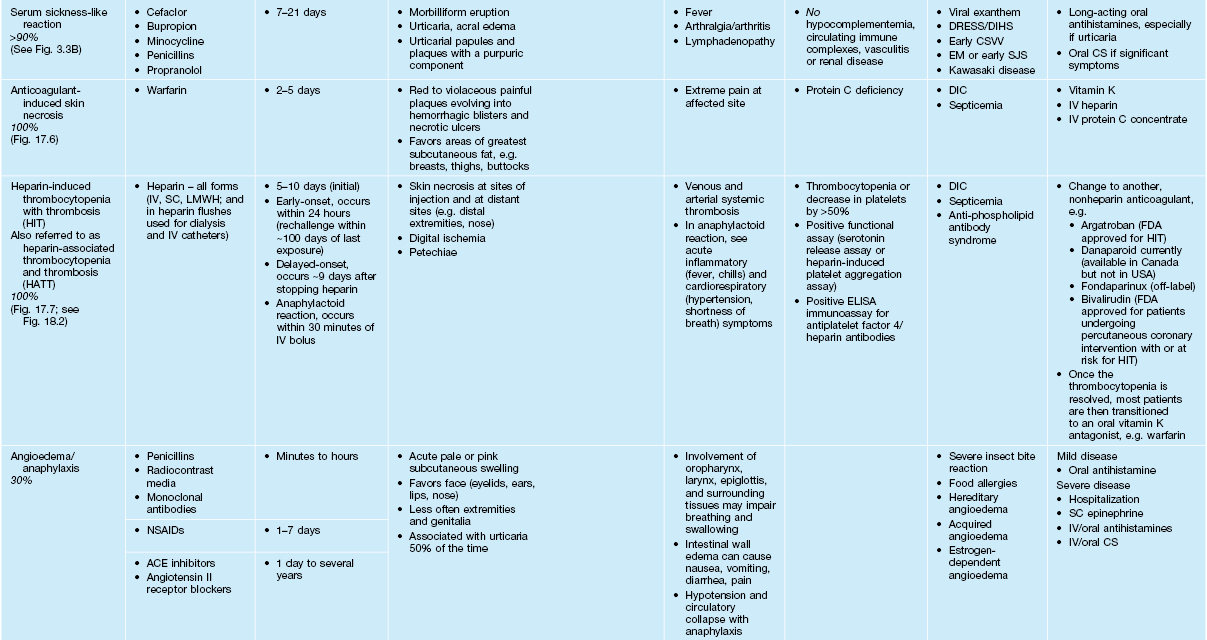

• Most common types of ACDR: morbilliform > urticaria > vasculitis (Table 17.3).

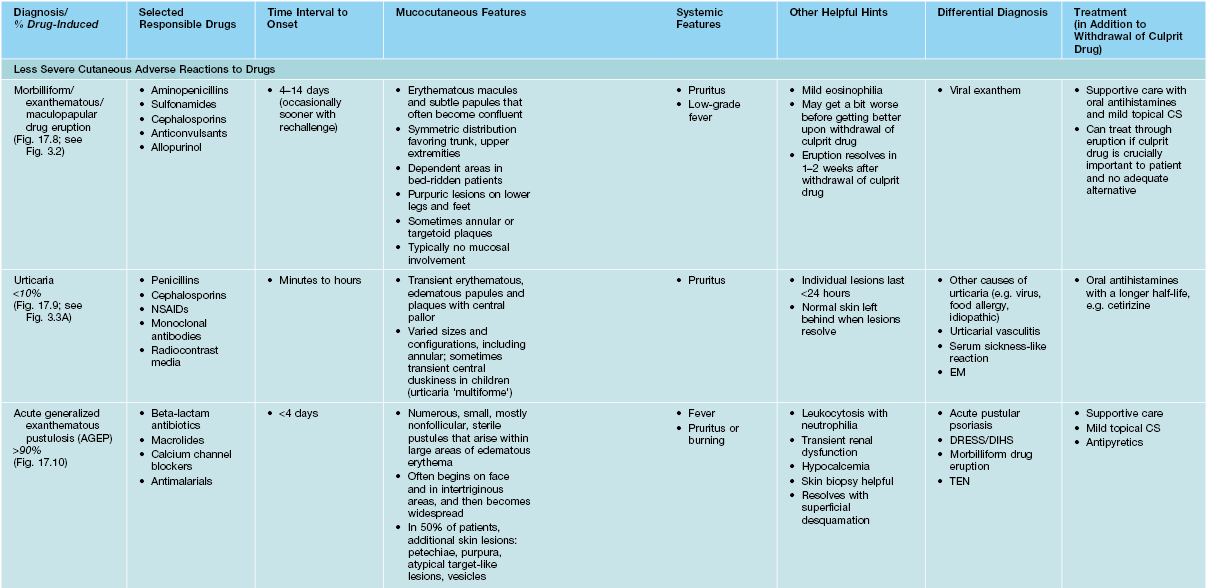

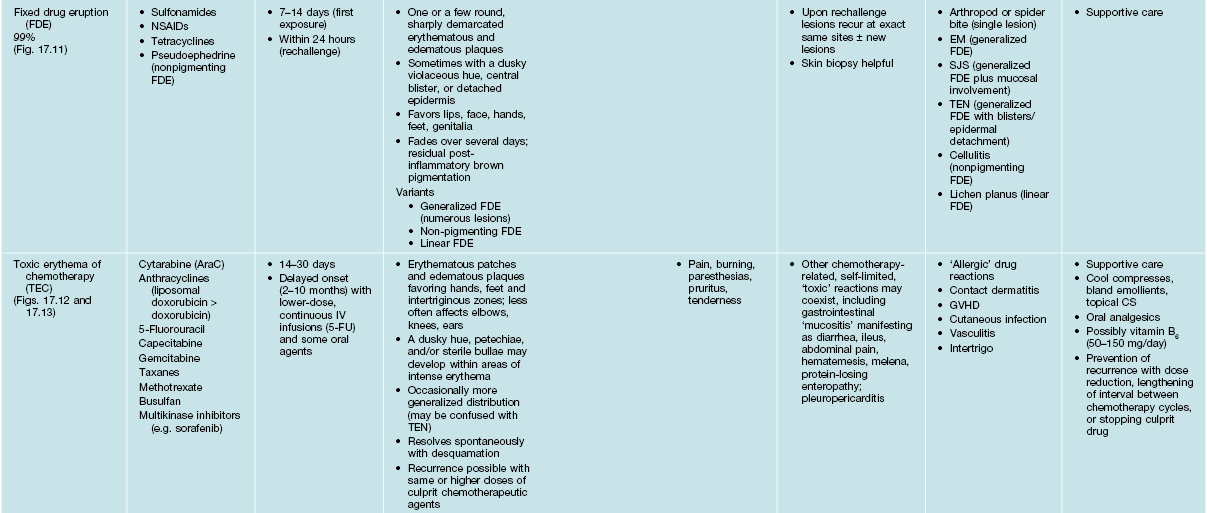

Table 17.3a

Characteristics of selected adverse cutaneous drug reactions (ACDR).

* Aromatic anticonvulsants, e.g. phenytoin, phenobarbital, and carbamazepine, are most often implicated.

SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; BSA, body surface area; URI, upper respiratory tract infection; LABD, linear IgA bullous dermatosis; SSSS, staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome; AGEP, acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; FDE, fixed drug eruption; ICU, intensive care unit; IV, intravenous; SC, subcutaneous; BUN/Cr, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine; ANCA, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; GI, gastrointestinal; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; DIF, direct immunofluorescence; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Table 17.3b

Characteristics of selected adverse cutaneous drug reactions (ACDR).

SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; EM, erythema multiforme; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil.

Fig. 17.3 Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Flaccid bullae leading to epidermal detachment (<10% body surface area) (A) and involvement of the conjunctivae (B) allow distinction from exanthematous drug eruptions.

Fig. 17.4 Drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS). Also known as drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS). Facial edema and multiple edematous papules are present. Courtesy, Kenneth Greer, MD.

Fig. 17.5 Serum sickness due to antithymocyte globulin. The purpuric lesions are due to small vessel vasculitis in this patient with aplastic anemia. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 17.6 Warfarin-induced skin necrosis. Retiform purpuric plaques with large hemorrhagic crusts and underlying ulcers on the abdominal pannus of a woman who recently initiated warfarin treatment. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 17.7 Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia with thrombosis syndrome (HIT). A Ischemia and necrosis of the foot. B Petechiae due to thrombocytopenia and an irregular area of cutaneous necrosis. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD. B, Courtesy Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 17.8 Exanthematous (morbilliform) drug eruptions. Numerous pink papules on the trunk due to a cephalosporin (A). Confluence of lesions on the trunk (B) and annular plaques on the forehead (C) secondary to phenobarbital.

Fig. 17.10 Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). A A positive patch test result 4 days following the application of 0.75% metronidazole in a patient with a previous pustular drug eruption to that medication. Diffuse erythema of the buttock (due to cephalosporin, (B) and face (due to metronidazole, (C) studded with sterile pustules. A and C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

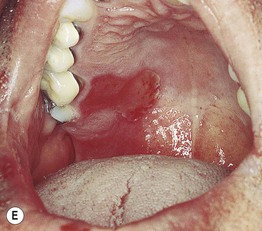

Fig. 17.11 Fixed drug eruptions (FDE). Well-demarcated erythematous (A) to violet-brown plaques that can develop a detached epidermis (B), bulla (C), or erosion (D, E) centrally. As lesions heal, circular or oval areas of hyperpigmentation are commonly seen (F). Responsible drugs were phenolphthalein (A), naproxen (B), ciprofloxacin (D), allopurinol (E), and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (F). C, Courtesy, Jean Revuz, MD; D, E, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; F, Courtesy, Mary Stone, MD.

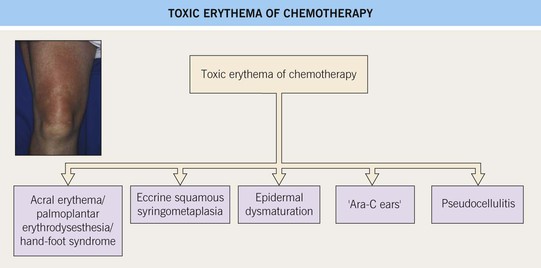

Fig. 17.12 Toxic erythema of chemotherapy (TEC). Use of a number of terms (especially those based on histologic findings), including palmoplantar erythrodysesthesia, eccrine squamous syringometaplasia, and epidermal dysmaturation, has created some confusion for clinicians. There is considerable overlap in the appearance of the symmetric erythematous patches, which can develop edema, erosions, desquamation, or purpura (depending on the patient’s platelet count), whether they favor acral sites, intertriginous zones, or the elbows and knees. ‘Toxic erythema of chemotherapy’ represents an encompassing term that allows simplification. In addition, there is no need to implicate additional diagnoses when lesions are not limited to the hands and feet. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 17.13 Toxic erythema of chemotherapy. A Erythema of the ears due to cytarabine (cytosine arabinoside), sometimes referred to as ‘Ara-C ears’; the petechiae are due to thrombocytopenia. B Toxic erythema of chemotherapy due to cytarabine, with obvious erythema of the plantar surface. C Acral erythema due to sorafenib. Note the erythema and bullae localizing to the palmar skin folds. D Axillary erythema and desquamation in a patient receiving busulfan plus fludarabine. Note that this eruption occurred 1 month after receiving these drugs. A, B, D, Courtesy, Jean Bolognia, MD, C, Courtesy, Peter W. Heald, MD.

• Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions (SCARs) cause significant morbidity and potential mortality, but fortunately only constitute ~2% of all ACDR.

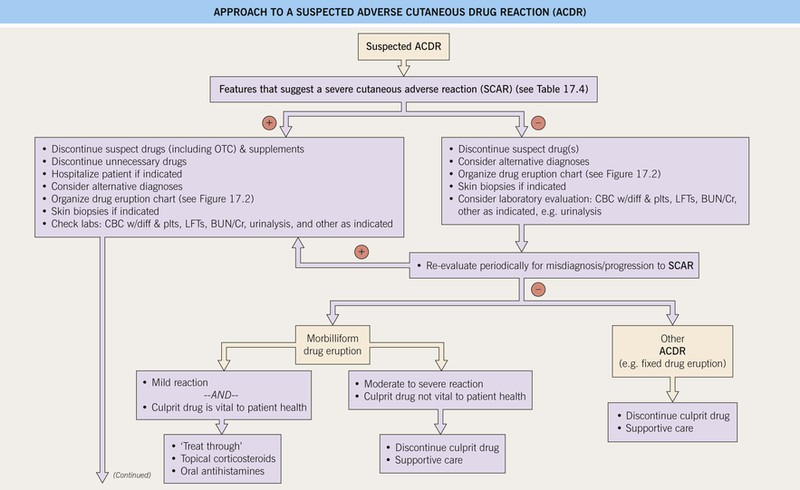

• SCARs that require immediate attention: Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS)/drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome (DIHS), vasculitis, serum sickness, serum sickness-like reaction, warfarin-induced skin necrosis, angioedema/anaphylaxis, and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis syndrome (HIT) (see Table 17.3 and Fig. 17.1).

Fig. 17.1 Approach to a suspected adverse cutaneous drug reaction (ACDR). SCAR, severe cutaneous adverse reaction to a drug; OTC, over-the-counter; CBC, complete blood count; diff, differential; plts, platelets; LFTs, liver function tests; BUN/Cr, blood urea nitrogen/creatinine; URI, upper respiratory illness (including sore throat); SJS, Stevens–Johnson syndrome; TEN, toxic epidermal necrolysis; ICU, intensive care unit; SC, subcutaneous; IV, intravenous; DRESS, drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms; DIHS, drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; HIT, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and thrombosis syndrome. Approach to a suspected adverse cutaneous drug reaction (ACDR).

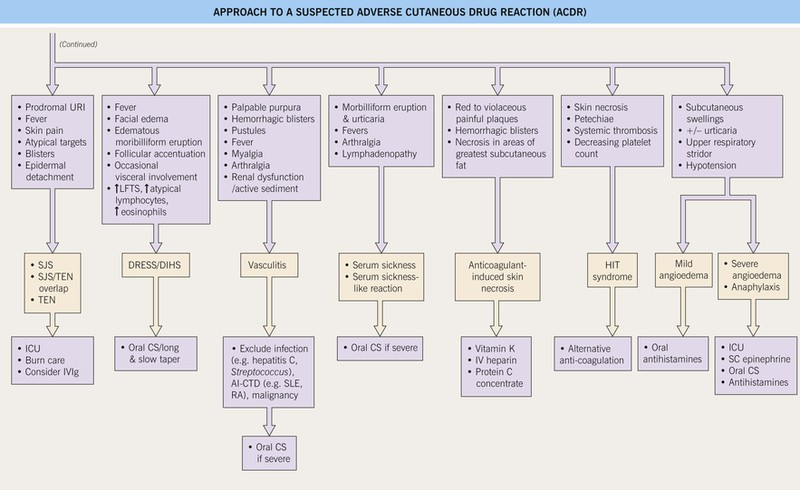

• Features that should alert one to the presence of a SCAR are outlined in Table 17.4.

Table 17.4

Features that suggest a severe cutaneous adverse reaction (SCAR) to a drug.

Adapted from: Roujeau JC, Stern RS. Severe adverse cutaneous reactions to drugs. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;331(19):1272–1285.

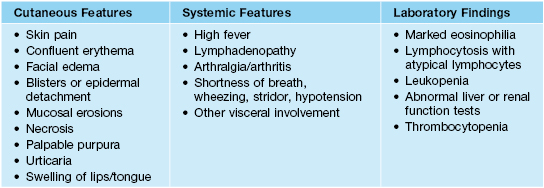

• A practical approach in determining the cause of an ACDR is outlined in Table 17.5.

Table 17.5

Logical approach to determine the cause of a drug eruption.

* Often inadvertent.

OTC, over-the-counter.

Courtesy, Jean Revuz MD and Laurence Valeyrie-Allanore MD.

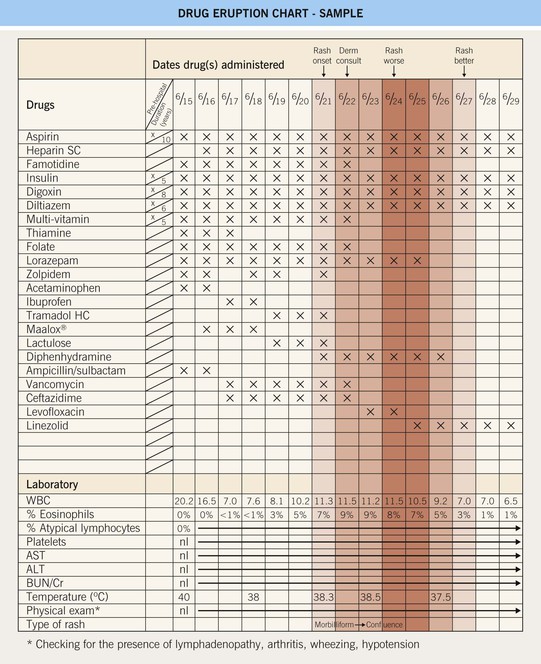

• Organizing pertinent information into a drug chart (see Fig. 17.2 and Appendix) can be helpful in synthesizing the available information.

Fig. 17.2 Drug eruption chart. This is a helpful working template for organizing all of the available patient information into one document for a patient with a suspected adverse cutaneous drug reaction (ACDR). Step 1: Compile all of the recently consumed or administered drugs (including prescription, over-the-counter, and supplements) into the chart. Step 2: Review and list the pertinent laboratory information and physical findings at the bottom of the chart. Step 3: Referring to Fig. 17.1, exclude a SCAR and categorize the type of ACDR. Step 4: Based on time intervals (see Table 17.3) and the most and least likely drugs to cause ACDR (see Table 17.2), begin to formulate the most likely culprit drugs and recommend their discontinuation. In addition, discontinue unnecessary drugs. Step 5: Longitudinal evaluation of the patient is necessary to (1) exclude progression to a SCAR, (2) determine the response upon discontinuation of the culprit drug (noting that it might ‘get worse before it gets better’), and (3) provide supportive care to the patient. In this sample patient, the most likely culprit drugs are ceftazidime > ampicillin/sulbactam > vancomycin; however, the multi-vitamin, folate, famotidine, zolpidem, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, tramadol, Maalox®, and lorazepam (must taper off and not abruptly stop) were also discontinued. Note that the discontinuation of levofloxacin by the primary physicians was not necessary. Refer to www.expertconsult.com for a blank template of the drug eruption chart. SC, subcutaneous; WBC, white blood cell count; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase.

• An approach to the management of a suspected ACDR is presented in Fig. 17.1.

• Additional reviews of specific types of drug reactions can be found in other chapters (Table 17.6).

Table 17.6

Additional specific types of drug-induced eruptions.

| Drug Reaction | Chapter Text |

| Sweet’s syndrome | Chapter 21 |

| Psoriasiform (Fig. 17.14) | Chapter 6 |

| Erythroderma | Chapter 8, Table 8.1 |

| Lichenoid | Chapter 9 |

| Urticaria | Chapter 14 |

| Stevens–Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis | Chapter 16 |

| Warfarin and heparin necrosis | Chapter 18 |

| Vasculitis | Chapter 19 |

| Pemphigus and bullous pemphigoid | Chapters 23 and 24 |

| Linear IgA bullous dermatosis (LABD) | Chapter 25, Table 25.1 |

| Acneiform/folliculitis | Chapters 29 and 31 |

| Hyper- and hypohidrosis | Chapter 32 |

| Lupus erythematosus (drug-induced SLE and drug-induced SCLE) | Chapter 33, Table 33.1 |

| Pseudoporphyria | Chapter 41, Table 41.1 |

| Hypopigmentation (skin and hair) | Chapter 54 |

| Hyperpigmentation and dyschromatosis | Chapter 55 |

| Hypertrichosis and hirsutism | Chapter 57 |

| Phototoxic and photoallergic | Chapter 73, Table 73.4 |

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SCLE, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus.

Fig. 17.14 Psoriasiform eruptions due to TNF-α inhibitors. A Widespread papulosquamous lesions in a patient being treated with infliximab for gastrointestinal GVHD. Histopathologically, there was no evidence of cutaneous GVHD. B Sterile pustulosis of the plantar surface developed in this patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had received infliximab for the previous 5 years. Neither patient had had a reduction in immunosuppression prior to the onset of the psoriasiform eruption. A, Courtesy, Dennis Cooper, MD. B, Courtesy, Chris Bunick, MD.

• Selected drug-induced eruptions due to chemotherapeutic agents are listed in Table 17.7.

Table 17.7

Drug-induced eruptions due to chemotherapeutic agents.

| Mucocutaneous Reactions | Responsible Drugs |

| Alopecia (these alopecias are usually reversible, except for busulfan-induced alopecia, which is often irreversible) | Alkylating agents: cyclophosphamide, ifosfamide, mechlorethamine Anthracyclines: daunorubicin, doxorubicin, idarubicin Taxanes: paclitaxel, docetaxel Topoisomerase 1 inhibitors: topotecan, irinotecan Etoposide, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D, busulfan |

| Mucositis | Daunorubicin, doxorubicin, high-dose MTX, high-dose melphalan, topotecan, cyclophosphamide, taxanes, continuous infusions of 5-FU and prodrugs of 5-FU |

| Extravasation reactions (e.g. chemical cellulitis, ulceration) | Anthracyclines, carmustine, 5-FU, vinblastine, vincristine, mitomycin C |

| Chemotherapy recall (tender sterile inflammatory nodules at sites of previous chemotherapy extravasation or administration) | 5-FU, mitomycin C, paclitaxel, doxorubicin, epirubicin |

| Hyperpigmentation (see Chapter 55) | Alkylating agents: busulfan, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, mechlorethamine Antimetabolites: 5-FU, 5-FU prodrugs (e.g. capecitabine, tegafur), MTX, hydroxyurea Antibiotics: bleomycin, doxorubicin |

| Mucosal hyperpigmentation | Busulfan, 5-FU, hydroxyurea, cyclophosphamide |

| Nail hyperpigmentation | 5-FU, cyclophosphamide, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, MTX, bleomycin |

| Onycholysis | Paclitaxel, docetaxel |

| Radiation recall | MTX, doxorubicin, daunorubicin, taxanes, dacarbazine, melphalan, capecitabine, gemcitabine, cytarabine, pemetrexed |

| Radiation enhancement | Doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, taxanes, 5-FU, etoposide, gemcitabine, MTX |

| Photosensitivity | 5-FU and 5-FU prodrugs, MTX, hydroxyurea, dacarbazine, mitomycin C, docetaxel |

| Inflammation of ‘keratoses’ | Actinic keratosis: 5-FU and 5-FU prodrugs, pentostatin Seborrheic keratosis: cytarabine, taxanes Disseminated superficial actinic porokeratosis: 5-FU and 5-FU prodrugs, taxanes |

| Ulcerations | Hydroxyurea (lower extremities) |

| Acneiform eruptions (including folliculitis) | Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors (EGFRI): e.g. erlotinib, cetuximab, panitumumab, lapatinib Corticosteroids |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | Fludarabine, hydroxyurea, topical BCNU, BRAF inhibitors |

MTX, methotrexate; 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; BCNU, carmustine.

• Localized injection site reactions to selected medications are outlined in Table 17.8.

Table 17.8

Reactions localized to sites of injections of medications (in addition to extravasation of those administered intravenously).

CSF, colony stimulating factor; G, granulocyte; GM, granulocyte–macrophage.

For further information see Ch. 21. From Dermatology, Third Edition.