Chapter 4 Drug Development, Regulation, and Prescription Writing

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| DEA | Drug Enforcement Administration |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| IND | Investigational new drug |

| IRB | Institutional Review Board |

| NDA | New drug application |

| NIH | National Institutes of Health |

| PMS | Postmarketing surveillance |

Therapeutic Overview

The discovery, development, and clinical introduction of new drugs is a process involving close cooperation among researchers, medical practitioners, the pharmaceutical industry, and the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The drug development process begins with the synthesis or isolation of a new compound with biological activity and potential therapeutic use. This entity must then pass through preclinical, clinical, and regulatory review stages before becoming available as a therapeutically safe and effective drug. Similar governmental agencies regulate the development and distribution of drugs in other countries.

CLINICAL TESTING AND INTRODUCTION OF NEW DRUGS

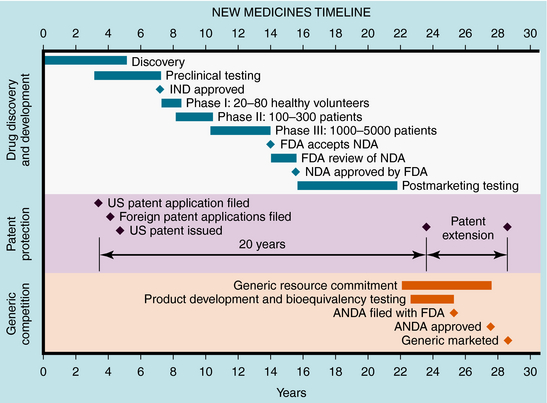

These studies provide the basis for drug labeling. The completion of these clinical studies may take 3 to 10 years and typically costs more than $300 million. Only one out of every five drugs that enter clinical trials receives FDA approval. When that one drug is marketed, it often represents an average $800 million investment, because the pharmaceutical company must pay for the thousands of failed drugs that did not meet approval (Fig. 4-1). The patent protection (17 years) of new drugs may be increased on some drugs, based upon delays in FDA approval (Patent Term Restoration Act, 1984). Extensions in patent life may also occur for products that provide pediatric studies to support pediatric labeling (Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act, 2002).

FIGURE 4–1 Stages of new drug development and the approval process, patent protection, and generic competition.

If suitable preclinical and clinical findings demonstrate efficacy with minimal toxicity, the sponsors can submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the FDA (see Fig. 4-1). In approving an NDA, the FDA ensures the drug’s safety and effectiveness for each use. Usually, the sponsor and the FDA review the data and negotiate on the detailed information to accompany the drug for its use. This includes contraindications, precautions, side effects, dosages, routes of administration, and frequency of administration. The NDA approval process usually takes 1 to 2 years, with drugs having the greatest potential benefit given priority. Drug applications are identified and placed into specific categories under an FDA classification system (Table 4-1). Postapproval research may be requested by the FDA as a condition of new drug approval. Such research may be used to speed drug approval, uncover unexpected adverse drug reactions, and define the incidence of known drug reactions under actual clinical use.

| Designation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| AA | Drugs for AIDS or complications related to AIDS |

| P | Priority |

| S | Standard |

| O | Orphan |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome.

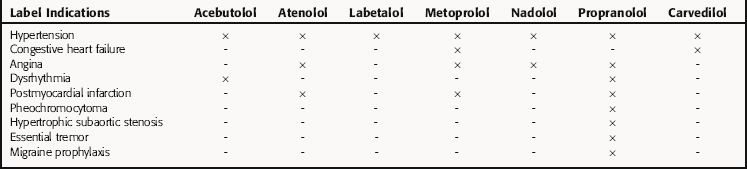

After NDA approval, the manufacturer promotes the new drug for the approved uses described on the label. During the post-NDA approval or marketing period (Phase 4), the safety of the new drug must be monitored during clinical use. The label information does not include all conditions in which a released drug is safe and effective. It should be noted that the FDA does not restrict use of approved drugs to those conditions described on the label; the physician is allowed to determine its most appropriate use. However, from both an ethical and liability standpoint, there should be compelling scientific evidence before a drug is used for an unapproved indication. Examples are β-adrenergic receptor blocking drugs, which often are used interchangeably for various indications, though not all have identical FDA-approved indications (Table 4-2).

Orphan Drugs, Pediatric Drug Testing, and Treatment INDs

Most drugs are studied, approved, and labeled for use in adults. At present, fewer than 25% of all drug labels include pediatric information. Young children often metabolize drugs at different rates than adults (see Chapter 3), and therefore testing is needed to clarify which doses work best in children. These studies would also help define the types of adverse reactions that are likely to occur. Current legislation allows for incentives to drug manufacturers for pediatric testing and provides funding to the NIH for research on drugs for which additional pediatric studies are needed.

When no Treatment IND is in effect for an investigational drug, a physician may obtain the drug for “compassionate use.” In such cases the physician submits a Treatment IND to the FDA requesting authorization to use an investigational drug for that purpose.

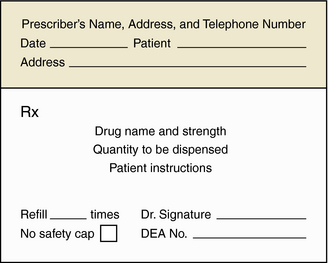

Prescriptions contain the following elements to facilitate interpretation by the pharmacist (Fig. 4-2):

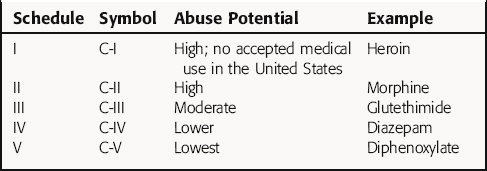

In the United States, many drugs require a prescription from a licensed practitioner (e.g., physician, dentist, veterinarian, podiatrist) before they can be dispensed by a pharmacist. In addition, use of specific drugs, called schedule drugs, with potential for abuse, are further restricted by the FDA, and special requirements must be met when these drugs are prescribed. These controlled drugs (Table 4-3) are classified according to their potential for abuse and include opioids, stimulants, and depressants. Schedule I drugs have a high abuse potential and no currently accepted medical use in the United States. Schedule II drugs also have a high potential for abuse, but they also have an accepted medical use; these drugs may not be refilled or prescribed by telephone. Other schedule drugs (III to IV) have low to moderate abuse potential and have a five-refill maximum, with the prescription invalid 6 months from the date of issue. Drugs in schedule V, which may be dispensed without a prescription if the patient is at least 18 years old, are distributed by a pharmacist, and only a limited quantity of the drug may be purchased (refer to the Controlled Substance Act of 1970).

Ascione FJ, Kirking DM, Gaither CA, Welage LS. Historical overview of generic medication policy. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2001;41:567-577.

Health G, Colburn WA. An evolution of drug development and clinical pharmacology during the 20th century. J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;40:918-929.

Kirking DM, Ascione FJ, Gaither CA, Welage LS. Economics and structure of the generic pharmaceutical industry. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2001;415:78-84.

McClellan M. Drug safety reform at the FDA–pendulum swing or systematic improvement? N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1700-1702.

Welage LS, Kirking DM, Ascione FJ, Gaither CA. Understanding the scientific issues embedded in the generic drug approval process. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 2001;41:856-867.

For more information about the evaluation and regulation of drugs by the FDA see: http://www.fda.gov/cder/index.html

: with

: with : without

: without