chapter 59 Domestic violence

WHAT IS DOMESTIC VIOLENCE?

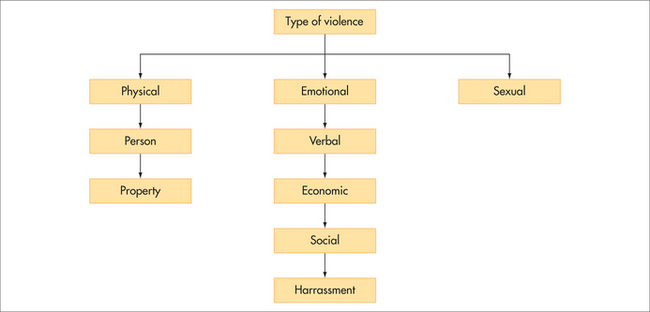

In the community, domestic violence is usually taken to mean physical violence between partners, usually perpetrated by the husband on the wife, although men may be victims and abuse does occur in same-sex relationships. Sometimes the term is used to refer to abuse that occurs in any relationship within households and thus would include child, elder and sibling abuse. This chapter concentrates on partner abuse (marriage, de facto relationship, boyfriend or girlfriend), which is a complex pattern of behaviours that includes emotional, physical and sexual abuse, not just simple acts of violence (Fig 59.1).

The World Health Organization uses the term intimate partner violence and defines it as:

Any behavior within an intimate relationship that causes physical, psychological or sexual harm to those in the relationship, includes: physical aggression, psychological abuse, forced intercourse & other forms of sexual coercion, various controlling behaviors.1

From a health perspective, domestic violence is best understood as a chronic syndrome characterised not by the episodes of physical violence that punctuate the problem but by the emotional abuse that the perpetrator uses to maintain control over the partner. Furthermore, as most victims of partner abuse report, the physical violence is the least-damaging abuse suffered. It is the relentless psychological abuse that cripples and isolates the victim and results in fear of the partner. Domestic violence against women is the focus of this chapter, because most abuse with serious health and other consequences is committed by men against their female partners.2

BACKGROUND AND PREVALENCE

Abuse of women by their partners or ex-partners is a worldwide phenomenon.3 The World Health Organization World Report on Violence and Health revealed that in 48 population-based surveys around the world, 10–69% of women had been physically assaulted by their partners at some stage in their lives.1 Clinical samples obtain higher rates than community surveys. For example, recent general practice studies in Australia, the United States, the United Kingdom and Ireland have found high lifetime physical abuse rates ranging from 23.3% to 41.0% of women, and 12-month rates from around 5% to 17%.4 A full-time general practitioner probably sees at least one abused woman each week, although she may not be presenting with obvious signs or symptoms. Similar rates are found in emergency departments, mental health clinics, antenatal care and drug and alcohol clinics. Today, on average, one in fifty women presenting to the emergency department do so because of domestic violence.

Thus women experiencing domestic violence present very frequently to healthcare services and require wide-ranging medical services. The societal economic impact is great, with an Australian study estimating that in 2002/03 the cost to the community of domestic violence was in the order of AUD$8.1 billion, with the main contributors being pain, suffering and premature mortality.5 The total cost of intimate partner violence to services and to the economy as a whole in the United Kingdom has been estimated at £3.1 billion and £5.7 billion a year, respectively.6

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES

Domestic violence can have short-term and long-term negative health consequences for survivors, even after the abuse has ended.7 Abused women experience many chronic health problems, with depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, chronic pain and gastrointestinal and gynaecological problems being the most common (Box 59.1). It is also a very common cause of femicide, with over 50% of all female murders being committed by their partners or ex-partners, in the United Kingdom and the United States. In Australia, a far higher percentage of Indigenous than non-Indigenous women are murdered by their partners.

EFFECT ON CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

Up to 60% of children witness their mother’s abuse.8 This witnessing includes:

A DIAGNOSTIC APPROACH

Intuitively, it would seem that early detection and intervention with women who have experienced domestic violence might improve health outcomes, but there is currently no empirical evidence for the effectiveness of routine screening. Although domestic violence is an important health problem, it fails to meet the most crucial criterion for screening—that early detection must enable early intervention, to reduce morbidity and/or mortality. Rather, opportunistic case finding in practice settings such as emergency departments, psychiatry clinics, antenatal clinics and general practices is appropriate with women who are presenting with the potential clinical indicators of domestic violence.9

HOW TO ASK ABOUT DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

Up to one-third of women disclose abuse to their GPs, particularly if asked in a non-judgmental, empathic way (Box 59.2). However, there are major internal and external barriers to women disclosing about domestic violence. Reasons given by women living in situations of domestic violence include fear, denial and disbelief, emotional bonds to partner, commitment to marriage, hope for change and staying for the sake of the children. Normalisation of violence (i.e. coming from a background where abuse was the norm) and women’s isolation, depression and stress play a major role in their non-disclosure. Feeling that they will not be believed by health practitioners and that available services will not be able to help or maintain confidentiality may reflect negative experiences in the past.

INTEGRATIVE MANAGEMENT

Managing partner abuse does not really follow the simple line of history taking, examination, diagnosis and referral. Rather, there are simple communication skills that the healthcare professional should exercise that women in situations of violence and abuse say they expect and hope for from their healthcare practitioner.10 Often women who feel supported see their GP as an advocate for them.

Women need emotional support from their healthcare practitioner, their multiple physical symptoms investigated and treated, their mental health issues managed, their injuries documented and their social and environmental situation acknowledged and validated. Apart from seeking help from doctors, many women in their attempts to heal look to alternative therapies (e.g. music therapy, art therapy), while others seek spiritual help from ministers and other religious leaders. Practitioners need to be aware that these are often a great source of comfort for women at times of stress from the abuse.

PREVENTION

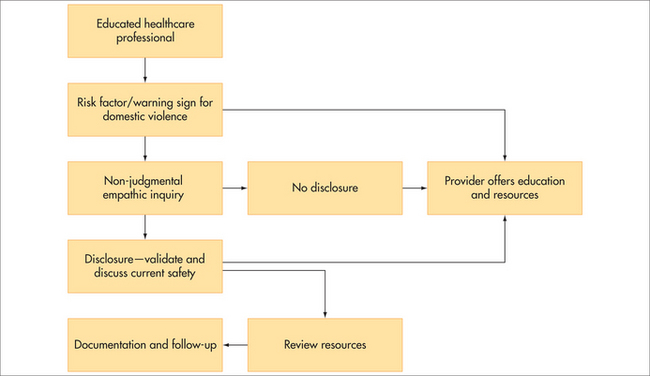

Practitioners do not have a major role in primary prevention of domestic violence (e.g. community campaigns and school programs). They can, however, play a role in prevention by modelling non-abusive workplace practices, by early intervention with children who are witnesses of domestic violence and by speaking out in public forums about this common social problem. Education at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels across the disciplines is necessary to provide an educated healthcare workforce (Fig 59.2), which is essential for interventions in the domestic violence area. Healthcare practitioners need to actively intervene, with this social condition that affects the health of women and their families.

INITIAL RESPONSE

All healthcare professionals need to be trained to be able to validate the experience of abuse, affirm that violence is unacceptable behaviour and express support, before any other response. Even if a woman does not choose to pursue other interventions or engage with other agencies, validation of her experience and the offer of support is an act that may in the long run contribute to her being able to change her situation (Box 59.3).

BOX 59.3 Possible validation statements if a woman discloses domestic violence

In addition to offering support, the practitioner needs to make an initial assessment of the woman’s safety (Box 59.4). This may be as simple as checking with the woman about whether it is safe for her (and her children) to return home. A more detailed risk assessment will include questions about escalation of abuse, the content of threats and direct and indirect abuse of the children.

REFERRAL TO EXTERNAL AGENCIES

In addition to assessing the woman’s safety, a key step for clinicians to whom women disclose domestic violence, particularly if it is current or recent violence, is offer of referral to specialist domestic violence support. This is provided in a variety of ways, usually by a non-governmental organisation or a social service agency; or sometimes it is government funded. Domestic violence advocacy, particularly for women who have actively sought help from professional services or are in a refuge setting, is likely to be beneficial. It has been shown to reduce abuse, increase social support and quality of life and lead to increased use of safety behaviours and accessing of community resources. For women identified in healthcare settings, we are unsure whether advocacy works, because of the small number and relatively poor design of current studies.11

SELF-HELP

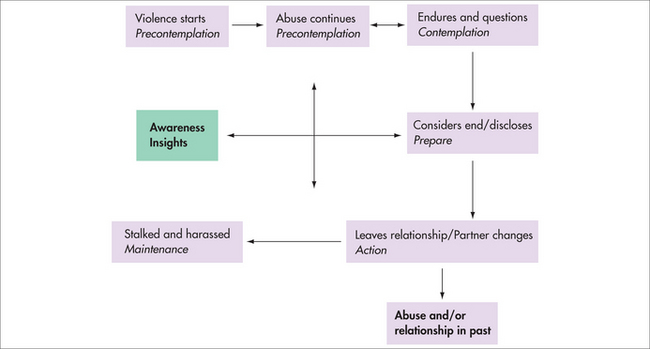

The literature identifies varying numbers of stages (Fig 59.3) that women undergo in dealing with domestic violence, and women may move in either direction along the path. For example, a woman often has to leave an abusive partner a number of times before the relationship is finally ended, and the abuse might not end when the relationship does. In the final stage, which is generally considered to be a lack of violence in a woman’s life, recovery is not returning to ‘normal’, but constructing a self built on the experience of having survived and left an abusive situation. Reclaiming the self may be a stage where women move from surviving to thriving. There are many self-help books, support groups and online support forums (chat rooms, bulletins and email groups) that women can access on this journey to recovery.

The importance of relating to other women who have shared experiences in order to reconstruct a self where abuse is no longer part of a woman’s life cannot be underestimated. In Figure 59.3, the concept of a catalyst for change that propels women towards acting to end the violence is introduced. The ‘turning point’ moment connects the external and internal in a moment of change. It generally coincides with an environmental shift (e.g. children becoming teenagers, getting a job, taking up study) and leads to an adjustment to the woman’s sense of self.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPY

There is evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy principles used in group or solo therapy may benefit survivors of abuse if delivered by therapists who have had additional training in dealing with domestic violence. They are not appropriate or even safe while a woman is still experiencing abuse from her partner.11

PERPETRATOR MANAGEMENT

Men who use violence in their relationships are at increased risk of depression, substance abuse or abuse in their childhood and it is unlikely that they will spontaneously disclose.12 Current evidence suggests that clinicians should ask men general questions about how things are at home, but then ask specifically about what happens when the couple argue. Offering ongoing support if he is willing to attempt change, and referral to an accredited behaviour change program, is a key component of management. Assessing the patient’s suicide risk and his family’s safety is vital. Although the evidence for effective interventions for perpetrators is not strong and is based mostly on mandatory programs, evidence from their partners suggests that for those men who do remain in programs, their partners’ quality of life improves.

Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals: new approaches to domestic violence. London: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2006.

Taft A, Hegarty K, Feder G, on behalf of the Guidelines Development Group. Management of the whole family when intimate partner violence is present: guidelines for the primary care physician. Melbourne, Australia: Victorian Government Department of Justice; 2006. www.racgp.org.au/Content/NavigationMenu/ClinicalResources/RACGPGuidelines/Familywomenviolence/Intimatepartnerabuse/20060507intimatepartnerviolence.pdf.

1 Krug E, Dahlberg L, Mercy J, et al. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2002.

2 Taft A, Hegarty K, Flood M. Are men and women equally violent to intimate partners? Aust NZ J Public Health. 2001;25(6):498-500.

3 Watts C, Zimmerman C. Violence against women: global scope and magnitude. Lancet. 2002;359:1232-1237.

4 Hegarty K. What is domestic violence and how common is it? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals: new approaches to domestic violence. London: Elsevier, 2006.

5 Partnerships Against Domestic Violence and Access Economics Pty Ltd. The cost of domestic violence to the Australian economy. Canberra: Australian Government, Office of the Status of Women, Commonwealth of Australia, 2004.

6 Walby S. The cost of domestic violence. London: Department of Trade and Industry, 2004.

7 Campbell J, Laughon K, Woods A. Impact of intimate partner abuse on physical and mental health: how does it present in clinical practice? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. London: Elsevier; 2006:43-60.

8 Smith J. The impact of intimate partner abuse on children. In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. London, UK: Elsevier, 2006.

9 Hegarty K, Feder G, Ramsay J. Identification of partner abuse in health care settings: should health professionals be screening? In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals. London: Elsevier, 2006.

10 Feder G, Hutson M, Ramsay J, et al. Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(1):22-37.

11 Ramsay J, Feder G, Rivas C. Interventions to reduce violence and promote the physical and psychosocial well-being of women who experience partner abuse: a systematic review. London: Department of Health, 2006.

12 Taft A, Shakespeare J. Managing the whole family when women are abused by intimate partners: challenges for health professionals. In: Roberts G, Hegarty K, Feder G, editors. Intimate partner abuse and health professionals: new approaches to domestic violence. London: Elsevier; 2006:145-163.