What Does Ulceration of a Melanoma Mean for Prognosis?

Ulceration is defined pathologically as the absence of intact epithelium overlying a melanoma. In patients with cutaneous melanoma, ulceration of the primary melanoma is a well-known prognostic factor associated with decreased disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS); presence or absence of ulceration has been incorporated into the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for cutaneous melanoma since the sixth edition in 2002 [1]. Although the factors underlying the prognostic significance of ulceration are still largely unknown, ulceration is undoubtedly a marker of unfavorable tumor biology. Recent data suggest that ulceration may be a predictive marker for response to adjuvant interferon (IFN) alfa-2b therapy. This article reviews the data surrounding the prognostic implications of ulceration in cutaneous melanoma.

Ulceration as negative prognostic factor

Ulceration was first identified as a negative prognostic factor in cutaneous melanoma by Allen and Spitz [2] and Tompkins [3] in 1953. Throughout the subsequent three decades, many other groups corroborated this finding [4–6]. However, thickness of the primary tumor is also a key prognostic factor in melanoma, and the presence of ulceration strongly correlates with thickness of the primary tumor. For example, in a study of 250 patients with cutaneous melanoma, the incidence of ulceration ranged from 12.5% for melanomas measuring less than 0.76 mm in thickness to 72.5% for melanomas measuring greater than 4 mm in thickness [7]. Thus, the possibility existed that thickness of the primary tumor was a confounding factor when ulceration was identified as a negative prognostic factor in cutaneous melanoma.

In 1978, to differentiate ulceration from thickness of the primary tumor as a separate predictor of outcome, Balch and colleagues [8] performed a multivariate analysis of factors associated with the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma in 339 patients. They found that ulceration was indeed an independent negative prognostic factor; the presence of ulceration predicted a worse outcome even when taking primary tumor thickness into account.

Balch’s group went on to consider the idea that the presence of an ulcer crater might lead to an underestimation of actual tumor thickness, because tumor thickness is by necessity measured to the base of the ulcer. They examined 85 melanomas with micrographically measurable ulceration depth, and found that the median depth of ulcer craters was only 0.08 mm. Even if the thickness of the ulcer crater was added to the thickness of the primary tumor, no patient would have changed to a higher Breslow thickness group; therefore, no patient would have been expected to have worse survival because of ulceration leading to an underestimation of actual tumor thickness [7].

Cross-sectional measurement of ulceration has also been performed to quantify the extent of ulceration necessary to confer prognostic significance [7,9]. Balch and colleagues [7] found that patients with ulcers less than 6 mm wide had a 5-year survival rate of 44%, but patients with ulcers greater than or equal to 6 mm had a 5-year survival rate of only 5% (P <.001). However, a recent study by Sarpa and colleagues [9] evaluated extent of ulceration as a proportion of the primary tumor diameter, and found that ulceration of as little as 5% of the tumor diameter was associated with a decrease in OS.

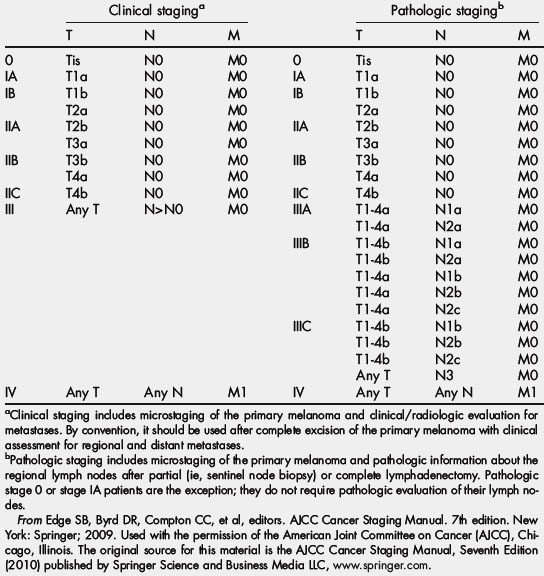

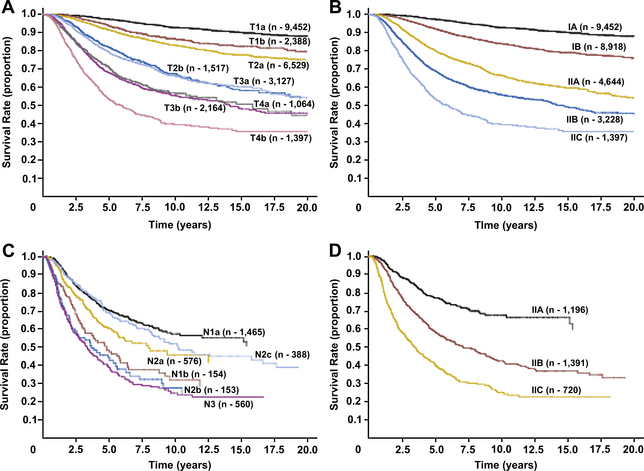

Because ulceration has consistently been demonstrated to be an independent negative prognostic factor in cutaneous melanoma, it was incorporated into the AJCC staging system in 2002 [1]. Analysis of independent large databases has validated the introduction of ulceration into the staging system [10], and ulceration continues to be included in the most recent AJCC staging system update [11]. The AJCC seventh edition (2009) TNM staging categories and anatomic stage groupings for cutaneous melanoma are shown in Table 1 and Table 2. Essentially, given equal tumor thickness, the presence of ulceration increases the stage to the next highest grouping. For example, a patient with a T1 melanoma with ulceration is expected to have the same survival as a patient with a T2 melanoma without ulceration. This phenomenon is illustrated in Fig. 1A, based on data from the AJCC Melanoma Staging Database (data through 2008), which included 30,946 patients with stages I, II, and III melanoma [11,12].

| T category | Thickness (mm) | Ulceration status/mitoses |

|---|---|---|

| Tis | NA | NA |

| T1 | ≤1 | a: Without ulceration and mitosis <1/mm2 |

| b: With ulceration or mitoses ≥1/mm2 | ||

| T2 | 1.01–2 | a: Without ulceration |

| b: With ulceration | ||

| T3 | 2.01–4 | a: Without ulceration |

| b: With ulceration | ||

| T4 | >4 | a: Without ulceration b: With ulceration |

| N category | Number of metastatic nodes | Nodal metastatic mass |

| N0 | 0 | NA |

| N1 | 1 | a: Micrometastasisa |

| b: Macrometastasisb | ||

| N2 | 2–3 | a: Micrometastasisa |

| b: Macrometastasisb | ||

| c: In transit metastasis/satellite(s) without metastatic nodes | ||

| N3 | 4+ metastatic nodes, or matted nodes, or in transit metastases/satellites with metastatic nodes | — |

| M category | Site | Serum LDH |

| M0 | No distant metastases | NA |

| M1a | Distant skin, subcutaneous, or nodal metastases | Normal |

| M1b | Lung metastases | Normal |

| M1c | All other visceral metastases | Normal |

| Any distant metastasis | Elevated |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; NA, not applicable.

From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edition. New York: Springer; 2009. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition (2010) published by Springer Science and Business Media LLC, www.springer.com.

(From Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al, editors. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th edition. New York: Springer; 2009. Used with the permission of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), Chicago, Illinois. The original source for this material is the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, Seventh Edition (2010) published by Springer Science and Business Media LLC, www.springer.com.)

Ulceration as predictor of sentinel lymph node involvement

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) status has been shown to be the most important single factor that predicts survival in patients with melanoma: patients with SLN-positive melanoma are 6.5 times more likely to die from melanoma than patients with negative nodes [13]. Several groups have looked specifically at the question of which factors independently predict SLN involvement by tumor; ulceration has been identified as an independent predictor of positive SLN biopsy [14–16].

Several years ago, our group used data from the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial (a large randomized prospective melanoma trial, described in detail next; Fig. 2) to examine this question with a larger sample size [17]. A total of 961 patients with cutaneous melanomas greater than or equal to 1 mm underwent SLN biopsy and were included in our study. The SLN biopsy was positive in 22% of patients, and ulceration was found to be an independent predictor of SLN involvement on multivariate analysis. Of note, Breslow thickness was also included in the multivariate model. Clearly, ulceration is a marker for more aggressive melanoma, independent of thickness of the primary melanoma.

Ulceration as predictor of response to adjuvant IFN therapy

Our group recently used data from the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial to explore the relationship between the presence of ulceration and response to adjuvant IFN therapy in cutaneous melanoma [18].

By way of background, IFN is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved adjuvant therapy for melanoma patients at high risk for disease recurrence. IFN was initially approved by the Food and Drug Administration in this setting because of the results of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) randomized controlled trial E1684, in which 287 patients with melanoma greater than 4 mm thick or positive regional lymph nodes were randomized to 1 year of adjuvant high-dose IFN or observation between 1984 and 1990. Initial results demonstrated an increase in DFS and OS in the group that received high-dose IFN compared with the group that was observed (median DFS 1.7 vs 1 year; OS 3.8 vs 2.8 years) [19]. Two subsequent Intergroup trials yielded conflicting data regarding the benefit of IFN in the adjuvant setting. In E1690, 642 patients with stage IIB or stage III melanoma were randomized to adjuvant high-dose IFN, adjuvant low-dose IFN, or observation between 1991 and 1995. The trial demonstrated an increase in DFS but not OS in the group that received high-dose IFN [20]. In E1694, 880 patients with stage IIB or stage III melanoma were randomized to receive either high-dose IFN or the ganglioside GM2/keyhole limpet hemocyanin vaccine in the adjuvant setting between 1996 and 1999. This trial was closed early because an interim analysis demonstrated an increase in both DFS and OS for the group receiving IFN [21]. A pooled update of all three trials subsequently demonstrated a persistent benefit in DFS for patients receiving high-dose IFN, but not a statistically significant increase in OS [22].

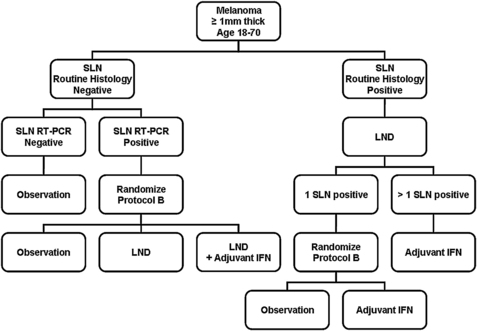

The Sunbelt Melanoma Trial is a randomized, prospective trial involving 79 centers across North America, and designed to evaluate the benefit of adjuvant IFN in high-risk patients with cutaneous melanoma. Between 1997 and 2003, over 3600 patients aged 18 to 70 years with cutaneous melanomas greater than or equal to 1 mm thick were enrolled. All patients underwent SLN biopsy for staging, and those in whom routine histopathology and immunohistochemistry demonstrated a positive SLN underwent completion lymph node dissection. If final pathology yielded only one positive SLN, patients were randomized (Protocol A) to observation alone versus adjuvant IFN. Patients with more than one positive SLN received adjuvant IFN. If initial routine histopathology and immunohistochemistry on the SLN was negative, reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) was performed on tissue from the SLN. Patients with negative RT-PCR underwent observation, whereas patients with a positive SLN by RT-PCR underwent randomization (Protocol B) to observation versus lymph node dissection versus lymph node dissection followed by adjuvant IFN. During randomization, patients were stratified by Breslow thickness and ulceration status. The schema for the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial is depicted in Fig. 2.

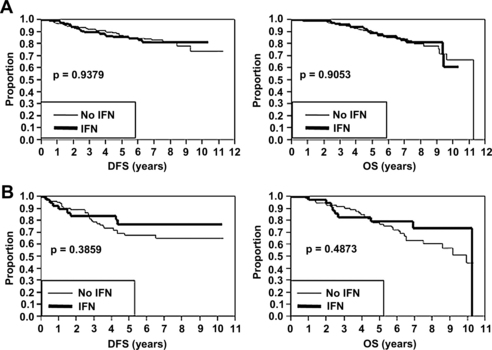

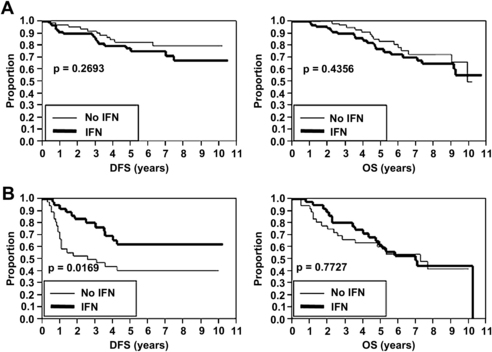

Overall, neither of the randomized protocols demonstrated a statistically significant increase in DFS or OS in the IFN treatment arms compared with controls [23]. However, we recently performed a post hoc analysis to investigate whether ulceration predicted improved response to adjuvant IFN therapy [18]. A total of 1769 patients with a median follow-up of 71 months were included in the analysis (458 with ulceration and 1311 without ulceration). As expected, the presence of ulceration was associated with significantly worse DFS and OS in both SLN-negative and SLN-positive patients. Subgroup analysis was subsequently performed to evaluate the effect of IFN based on ulceration status. In SLN-negative patients (Protocol B), adjuvant IFN therapy did not result in increased DFS or OS regardless of the presence or absence of ulceration (Fig. 3). Likewise, in SLN-positive patients (Protocol A) without ulceration, adjuvant IFN therapy did not result in increased DFS or OS (Fig. 4A). However, in SLN-positive patients (Protocol A) with ulceration, adjuvant IFN was associated with an increase in DFS (see Fig. 4B). As in the other subgroups, adjuvant IFN did not result in increased OS (see Fig. 4B). These data suggest that ulceration status may be useful in identifying a subset of high-risk melanoma patients that can benefit from adjuvant IFN therapy, and in which the toxicity of IFN may be justified.

There are several limitations that must be acknowledged. Although patients were stratified by ulceration at the time of randomization, the previously mentioned results represent a post hoc analysis, and not a prospectively planned analysis of the Sunbelt Melanoma Trial. In addition, because it is a subgroup analysis, some of the subgroup sample sizes are small; for example, the subgroup with SLN-positive melanoma and ulceration contained only 75 patients. However, our results are concordant with those of another major randomized melanoma trial: post hoc subgroup analysis of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) trials 18952 and 18991 demonstrated that adjuvant therapy with pegylated IFN was associated with improved OS in stage IIb and stage III (N1) patients with ulcerated primary melanomas but not in patients without ulceration [24].

Ulceration and underlying molecular mechanisms

The mechanisms underlying the prognostic significance of ulceration remain poorly understood. The two most well-founded hypotheses include the idea that ulceration is a surrogate for underlying molecular features of the tumor or the host that favors aggressive behavior, or that ulceration itself directly leads to early tumor dissemination, perhaps by alterations in the local environment [25].

There are some data to support ulceration as a phenotypic expression of unfavorable genetics and aggressive tumor biology. Several investigators have explored the association between ulceration and increased mitotic rate, tumor vascularity, or tumor invasion as possible explanations for the poorer outcome related to ulceration [26–29]. For example, Kashani-Sabet and colleagues [29] included vascular involvement and tumor vascularity in a multivariate model using a cohort of 526 patients, and found that ulceration was no longer an independent predictor of poorer outcome. This and other studies suggest that ulceration may be a surrogate for vascular interactions occurring within the tumor.

Matrix proteins have also been considered as possible factors contributing to the negative prognostic significance of ulceration. Osteopontin is a glycophosphotoprotein and cytokine that normally plays a role in inflammation, remodeling, and wound healing; in tumors, it can facilitate invasion, cell migration, anchorage-independent tumor cell growth, and prevention of tumor cell apoptosis [25]. CCN3 is another matrix protein that inhibits melanocyte proliferation and prevents melanocype invasion. CCN3 is present in superficial melanoma cells, but is absent in melanoma cells deep in the dermis or in lymph nodes [30]; perhaps the microenvironment in ulcers allows CCN3-depleted cells to invade [25].

Specific gene mutations may also be responsible for the poorer outcome seen in patients with ulceration. A study by Ellerhorst and colleagues [31] evaluated 223 melanoma specimens for presence of NRAS and BRAF mutations. Approximately 15% of tumors were found to be NRAS mutants, 50% were found to be BRAF mutants, 35% were wild-type at both locations, and only approximately 1% of tumors contained both mutations. NRAS mutants were associated with greater Breslow depth of tumor, but BRAF mutations were associated with ulceration. Presence of a mutation predicted a greater likelihood of presenting with regional disease, but neither mutation was associated with poorer survival. Because approximately half of cutaneous melanomas express BRAF mutations, BRAF is currently under investigation as a candidate for targeted therapy.

Ulceration in and of itself may also be responsible for early spread and consequent aggressive behavior of melanoma. One mechanism with some evidence involves the relationship between melanocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. Normally, melanocytes express E-cadherin and form gap junctions with keratinocytes above the dermal–epidermal junction; keratinocytes control melanocyte growth and expression of normal melanocyte cell surface markers. If the epidermal basement membrane loses its integrity (as in ulceration), melanoma cells can penetrate through the dermal–epidermal junction. Melanoma cells seem to switch to expression of N-cadherin and form attachments to fibroblasts instead of keratinocytes. This allows overproduction of growth factors and other mediators that can lead to tumor proliferation [25].