22

Disorders of the vulva

Introduction

The vulva consists of the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris and the vestibule (see Fig. 3.1). It is covered with keratinizing squamous epithelium, unlike the vaginal mucosa, which is covered with non-keratinizing squamous epithelium. The labia majora are hair-bearing and contain sweat and sebaceous glands: from an embryological viewpoint, they are analogous to the scrotum. Bartholin’s glands are situated in the posterior part of the labia, one on each side of the vestibule. The lymphatics of the vulva drain to the inguinal nodes and then to the external iliac nodes. The area is richly supplied with blood vessels.

Examination of the vulva

Before direct examination of the vulva, a general dermatological examination may be useful, particularly:

![]() the nail beds for signs of pitting (found in psoriasis)

the nail beds for signs of pitting (found in psoriasis)

![]() the extensor surfaces (elbows and knees) also for features of psoriasis

the extensor surfaces (elbows and knees) also for features of psoriasis

![]() the flexor surfaces for lichen planus and dermatitis

the flexor surfaces for lichen planus and dermatitis

![]() the mouth for other features of lichen planus.

the mouth for other features of lichen planus.

The vulva may than be inspected under a good light, as described on page 29. If necessary, closer inspection is possible using a colposcope.

Simple vulval conditions

Urethral caruncle

A urethral caruncle is a polypoidal outgrowth from the edge of the urethra, which is most commonly seen after the menopause. The tissue is soft, red and smooth and appears as an eversion of the urethral mucosa. Most women are asymptomatic, but others experience dysuria, frequency, urgency and focal tenderness. If there are any suspicious features, an excision and biopsy may be required to exclude the very rare possibility of a urethral carcinoma.

Bartholin’s cysts

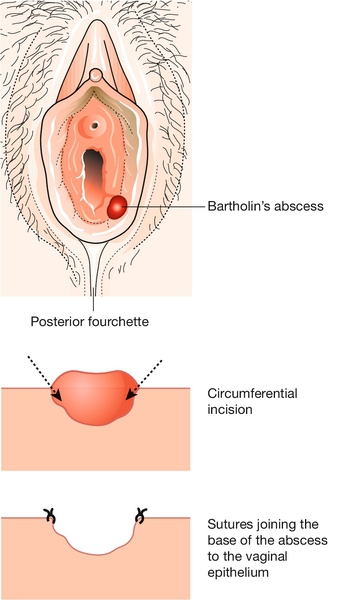

The greater vestibular, or Bartholin’s, glands lie in the subcutaneous tissue below the lower third of the labium majus and open via ducts to the vestibule between the hymenal orifice and the labia minora. They secrete mucus, particularly at the time of intercourse. If the duct becomes blocked, a tense retention cyst forms, and if there is super-added infection, a painful abscess develops. The abscess can be incised and drained, usually under general anaesthesia, with the incision on the inner aspect of the labium so that secretions bathe the introitus rather than the outside of the vulva. To prevent the cyst reforming, the fistula is kept open by suturing its edges to the surrounding skin, a procedure known as marsupialization (Fig. 22.1). Bartholin’s gland carcinoma is rare.

The lower part of the abscess cavity granulates and heals during the subsequent weeks.

Small cysts

The commonest small vulval cysts are usually either inclusion cysts or sebaceous cysts. Inclusion cysts form because epithelium is trapped in the epidermis, usually following obstetric trauma or episiotomy. They are usually asymptomatic and need no treatment. Sebaceous cysts are usually multiple, mobile, non-tender, white or yellow, filled with a cottage cheese-like substance and more common in the anterior half of the vulva. Excision may be requested by the patient.

Cysts in an episiotomy scar can be tender and need excision. Infected cysts need to be excised and drained, and recurrent infections should be treated by excision in their non-acute phase.

Moles

Vulval moles are usually asymptomatic but become more pigmented at puberty. Any other change in a vulval naevus is an indication for removal. There is a good case to be made for removing all vulval moles, as approximately 2% of malignant melanomas in women arise from the vulva.

Fibroma, lipoma, hidradenoma

Fibromas and lipomas are benign, mobile tumours of fibrous tissue and fat, respectively. Hidradenomas are rare tumours of sweat glands near the surface of the labia. All are benign, but the diagnosis is usually only made once they have been excised.

Haematoma

The commonest cause of a vulval haematoma is vaginal delivery. It may also occur following any vulval operation, or by ‘falling astride’ accidents, particularly in children. The possibility of sexual assault should be borne in mind in this situation. Vulval haematomas usually present with severe pain, and evacuation under general anaesthesia is often required.

Simple atrophy

Elderly women develop vaginal, vulval and clitoral atrophy as part of the normal ageing process of skin. In severe cases, the thin vulval skin, terminal urethra and fourchette cause dysuria and superficial dyspareunia, the labia minora may fuse and bury the clitoris. Introital stenoses can make coitus impossible. A simple effective moisturizer rubbed into the vulva is effective, although some advocate topical oestrogen replacement. There is a small amount of systemic absorption with topical oestrogen therapy, and, if this route is chosen, treatment should be for no more than 2 or 3 months without either a break or a short course of progesterone to prevent endometrial stimulation.

Ulcers

These may be:

![]() aphthous (yellow base)

aphthous (yellow base)

![]() herpetic (exquisitely painful multiple ulceration, pp. 180, 186)

herpetic (exquisitely painful multiple ulceration, pp. 180, 186)

![]() syphilitic (indurated and painless, p. 188)

syphilitic (indurated and painless, p. 188)

![]() associated with Crohn disease (‘like knife cuts in skin’)

associated with Crohn disease (‘like knife cuts in skin’)

![]() a feature of Behçet syndrome (a chronic painful condition with aphthous genital and ocular ulceration)

a feature of Behçet syndrome (a chronic painful condition with aphthous genital and ocular ulceration)

![]() malignant (see below)

malignant (see below)

![]() associated with lichen planus (see below) or Stevens–Johnson syndrome

associated with lichen planus (see below) or Stevens–Johnson syndrome

![]() tropical (lymphogranuloma venereum, chancroid, granuloma inguinale).

tropical (lymphogranuloma venereum, chancroid, granuloma inguinale).

Treatment depends on the cause. The management of Behçet syndrome is difficult, but the combined oral contraceptive or topical steroids may be tried.

Infection

Candida, vulval warts, herpes, lymphogranuloma venereum, scabies, granuloma inguinale, tinea, chancroid and syphilis are discussed in Chapter 24.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic unrelenting infection of the sweat glands. The glands become obstructed and chronic inflammation follows. Long-term antibiotics reduce further attacks, but the only cure is local excision.

Dermatoses

Vulval ‘dystrophy’ is an abnormality of vulval epithelium. Epithelial growth may be hypoplastic, hyperplastic or abnormal in some other way.

Lichen sclerosus

This chronic and recurrent condition can present at any age, but is more common in the older patient and usually presents with pruritus. Less commonly, presentation is with dyspareunia or pain. It is an autoimmune condition and there is an association with other autoimmune disorders, including pernicious anaemia, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), primary biliary cirrhosis and bullous pemphigoid. Histologically, the epidermis appears thin, with loss of rete ridges. The superficial dermis is hyalinized and a band of chronic inflammatory cells is seen beneath it.

Clinically, the skin appears white, thin and crinkly, but may be thickened and keratotic if there is coexistent squamous cell hyperplasia (Fig. 22.2). There may also be clitoral or labial atrophy, with loss of the normal vulval features, such as recession of the clitoral hood and shrinkage of the labia minora. Diagnosis is by biopsy. Lichen sclerosus is non-neoplastic but may coexist with vulval intraepithelial neoplasia and there is an association with subsequent development of vulval squamous cell carcinoma in 2–5% of cases. Initial follow-up is required to ensure that the patient is managing her symptoms and there are no suspicious skin changes. Once symptoms are controlled, then clinical review should be prompted by a change in symptom, a failure for routine management to control symptoms or a concern regarding the skin features.

The skin is white, with some reddened areas, and adhesions have significantly narrowed the introitus.

Treatment is required particularly if the condition is symptomatic, and initially is usually with a potent topical steroid cream (e.g. Dermovate b.d.) reducing gradually over a few months to a milder preparation (e.g. 1% hydrocortisone b.d., o.d. or less) as symptoms require. An emollient such as Oilatum or Diprobase is symptomatically beneficial. The patient should also cut her nails to try to break the itch–scratch–itch cycle. Avoidance of soaps, perfumed products and baby wipes is recommended. A non-fragranced, non-biological washing powder should be used. Vulvectomy has no role, the recurrence rate after surgery being around 50%.

Squamous cell hyperplasia

Squamous epithelial hyperplasia is characterized by thickened hyperkeratotic skin with white, itchy plaques. Pruritus is usually severe. Diagnosis is again by biopsy, and treatment is as for lichen sclerosus.

Other dermatoses

Allergic/irritant dermatosis

The vulval skin, especially the introitus, is not uncommonly affected by dermatitis. The dermatitis is either due to an irritant (non-immunological) or a true allergy (immunological aetiology). The chemicals causing hypersensitivity of the vulval skin include cosmetics, perfumes, contraceptive lubricants, sprays and douches. Detergents, dyes, softeners, bleaches, soaps and chlorine used to clean undergarments can also cause irritation. In severe cases, hypersensitivity may develop to local anaesthetic creams and even steroid preparations.

Women with contact dermatitis have a red inflamed vulva with features of eczema, and patch-testing may identify local irritants. Temporary relief may be obtained with vulval moisturizers (e.g. Dermol 500 in a daily bath), emollients (e.g. Epaderm) and topical corticosteroids (e.g. a month’s course of topical Dermovate). As before, lesions that do not respond should be biopsied to confirm the diagnosis.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis manifests as a well circumscribed, erythematous eruption, with superficial scaling and it may often have a plaque that may extend to the thigh. The diagnosis is easier to make if there is evidence of extra-genital psoriasis or there are nail changes. Because the vulva is often moist, it is often difficult to distinguish psoriasis from candidal infection or dermatitis. Candida should be excluded. The lesions may be treated with topical preparations, ultraviolet light, steroid creams or other suitable formulations.

Intertrigo with Candida

Intertrigo refers to a moist inflammatory dermatitis, which can occur in any body-fold because of apposition and chafing of skin surfaces. Skin-folds are more likely to rub together in those who are overweight and in those who use occlusive clothing.

The skin is sore, macerated and often red, inflamed and cracked. Weight loss, local hygiene, and ventilation should be encouraged, for example the use of stockings and cotton underclothes rather than tights and nylon pants.

Candida often complicates intertrigo and should be treated as on page 182. Providing there is no candidal infection, steroid creams may be used to relieve inflammation.

Lichen planus

Lichen planus is a chronic pruritic, purple, papular rash involving the vulva and flexor surfaces. It can affect other flexor surfaces and oral mucous membranes, and the diagnosis may be supported by the finding of other lesions such as Wickham striae in the buccal mucosa. It is usually idiopathic, but can be drug-related. Treatment is with potent topical steroids or ultraviolet light, and it tends to resolve within 2 years. Surgery should be avoided.

Pruritus

Pruritus describes an intense itching with a desire to scratch. It is commoner in those aged over 40 years, and symptoms are often most severe under times of stress or depression. There are numerous aetiologies (Box. 22.1).

A biopsy may be necessary to establish the diagnosis, and patch-testing may be of help. It is important to break the itch–scratch–itch cycle and strong short-term topical steroids will reduce the local inflammation caused by scratching. Application of a strong steroid cream twice daily for 3 weeks, followed by hydrocortisone cream 1% daily as maintenance, is useful, as is the use of soap substitutes (e.g. Oilatum). Irritants and bath-water additives should be avoided, soap substitutes used, the area dried gently (e.g. with a hairdryer), loose cotton clothing worn and nylon tights avoided. Antihistamines may also be of help. Coexisting depression may also warrant treatment.

Vulvodynia

This is chronic vulvar discomfort characterized by the complaints of burning, stinging, irritation or rawness with no diagnosis having been identified. There may also be pruritus. The condition may be localized, vestibulodynia, with erythema, severe pain on entry or to vestibular touch, and tenderness to pressure localized within the vestibule. The condition may also be generalized, dysaesthetic vulvodynia. No one factor can be identified as the specific cause. It may also occasionally be associated with previous sexual abuse.

There may be a response to low-dose tricyclic antidepressants (e.g. amitriptyline). Symptomatic relief can also be gained by the use of topical local anaesthetics. Due to the complex nature of this symptom, management can often be difficult and refractory cases should be reviewed in specialist multidisciplinary clinics where physiotherapy, psychological counselling, pain management and behavioural modification can be explored.

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasia refers to the presence of neoplastic cells within the confines of the vulval epithelium. In 2004, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Diseases (ISSVD) reclassified VIN. They now recommend that the term VIN be used for what was previously described as high-grade VIN (VIN 2 or 3). VIN is further described as usual-type (or undifferentiated type) or the less common differentiated type.

Usual-type (or undifferentiated type) is associated with human papilloma virus. The less common differentiated type is often encountered along with lichen sclerosis, especially where invasive squamous cancers are identified. Many are asymptomatic, although pruritus is present in up to two-thirds and pain is an occasional feature. Lesions may be papular and rough surfaced, resembling warts (Fig. 22.3) or macular with indistinct borders. White lesions represent hyperkeratosis and pigmentation can also be seen. The lesions can be multifocal or unifocal. There is also an association in HPV-related cases with intraepithelial neoplasia of the cervix, vagina and peri-anal areas.

Fig. 22.3High-grade VIN of the left labia majora.

In this case, the lesion is rough surfaced, not unlike the appearance of wart virus infection, but lesions are also commonly macular with indistinct borders.

Diagnosis is by biopsy, which may be taken at vulvoscopy, using 5% acetic acid as at colposcopy, under either local or general anaesthesia. The opportunity should be taken to look at the cervix at the same time, as there is an association with CIN. As the natural history is so uncertain, treatment is controversial. Regression has been observed but progression of high-grade VIN to invasion may occur in approximately 5% of cases, and up to 15% of those with high-grade VIN may have superficial invading vulval cancer.

Treatment of VIN includes surgical excision to obtain clear margins with plastic surgical reconstruction for extensive areas; immunomodulators such as imiquimod cream (Aldara) or laser ablation has been employed where there is no concern regarding malignancy. Close follow-up is required as the disease can recur. Smoking is a potent cofactor for the development of high-grade VIN and help with respect to smoking cessation, should be offered.

Paget disease (extra-mammary Paget disease)

In this uncommon condition, there is a poorly demarcated, often multifocal, eczematoid lesion, associated in 10% with adenocarcinoma either in the pelvis or at a distant site. The development of symptoms may precede the development of cancer by 10–15 years. Treatment is by wide local excision but due to the indistinct nature of the margins it can be difficult to obtain clearance. Recurrences are common.

Vulval carcinoma

Vulval cancer is relatively uncommon. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 90% of vulval cancers. Approximately 5% of vulval malignancies are malignant melanomas and the others include Bartholin’s gland cancer, basal cell carcinomas and sarcomas. It is usually a disease of older women (60 + years) and, like cervical cancer, is commoner in cigarette smokers and women who are immunocompromised.

Clinical presentation

Most women will present with a history of longstanding vulval irritation or pruritus, and some will have had a previous history of lichen sclerosus. A lump or ulcer is common (Fig. 22.4). As the disease advances, the tumour grows and focal necrosis may cause discharge and pain. The diagnosis is confirmed by histological examination of a biopsy.

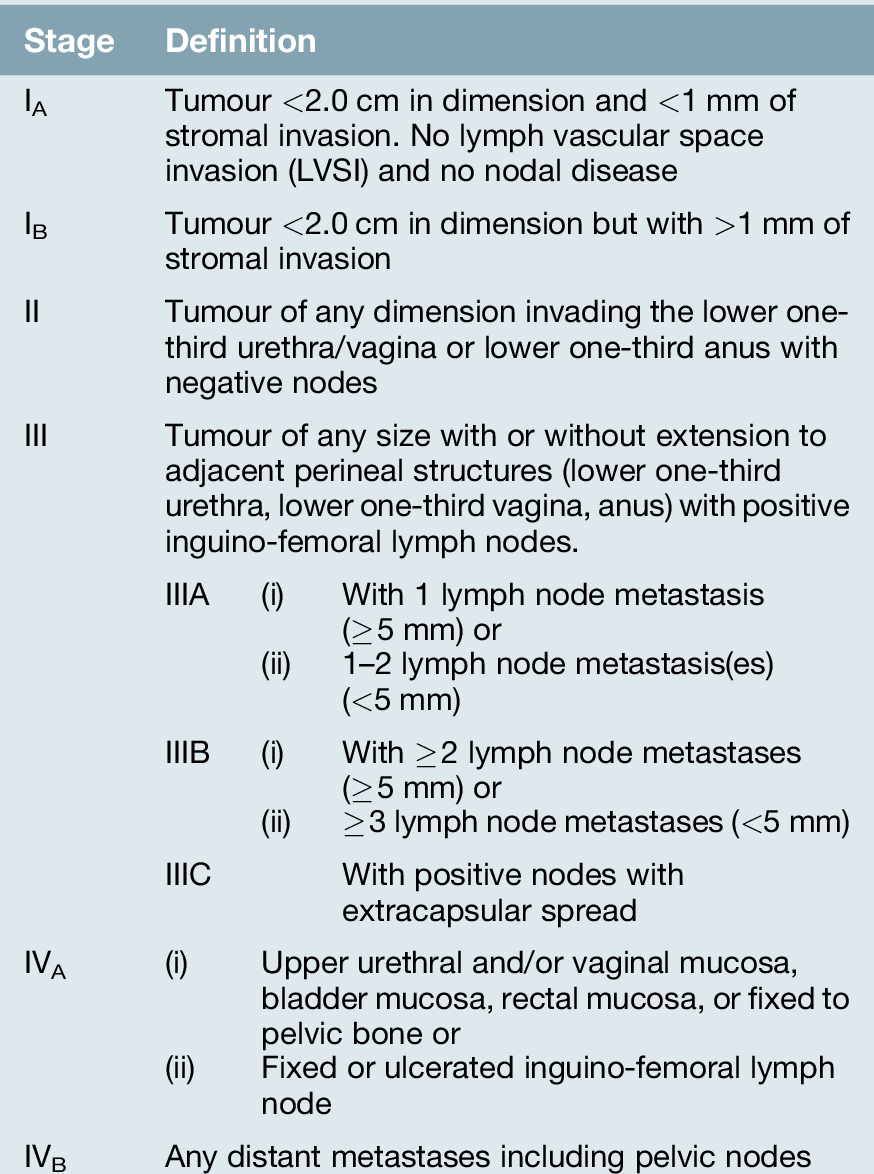

Pathophysiology

Squamous cell carcinoma spreads to the inguinal nodes and from there, to the external iliac nodes in the pelvis (Table 22.1). Unless the lesion has only penetrated the basement membrane by < 1 mm, node involvement can occur and may include both the superficial and deep inguinal lymph node systems.

Surgical management

The treatment of vulval carcinoma is surgical excision, either a wide local excision or vulvectomy, where this can be achieved without compromising bladder or bowel function. The addition of groin node lymphadenectomy should be performed where the depth of invasion is > 1 mm. It is appropriate to carry out only a unilateral exploration if the lesion is well lateralized > 1 cm from a midline structure such as the clitoris or posterior fourchette. In all other cases, a bilateral groin node dissection is required. Distant metastases are not a contraindication to radical vulval surgery, as death from a large fungating genital neoplasm or erosion of the femoral artery or vein by metastatic groin nodes is very unpleasant.

The groin explorations are carried out through separate incisions, and the wound will often be drained for around 7–10 days under suction, as lymph fluid accumulates and breakdown is common. To reduce the associated morbidity from groin node dissection the technique of sentinel node biopsy has been explored and there is growing evidence from large scale observational studies that this is an acceptable technique with reduced morbidity and false negative rates of 1%. If there is significant groin node involvement, it may be necessary to give adjuvant pelvic node radiotherapy as well.

The commonest complication of a radical vulvectomy is breakdown of the wound, which may take weeks to heal. To reduce the morbidity, then plastic surgical reconstruction can be offered. In addition, these women are often elderly, immobile and have had surgery on their pelvic vessels close to the femoral vein, leaving them at a high risk of venous thromboembolic disease. Long-term sequelae of surgery include vulval mutilation, if plastic surgical reconstruction is not offered, and lymphoedema. The 5-year survival is around 80% if groin nodes are negative and 40% if positive.

Recurrence

Recurrence of the excised tumour at the primary site is reduced where a 10 mm margin has been achieved. The epithelium is likely to be unstable and there may be multifocal pre-invasive lesions from which new vulval tumours may arise. Treatment of recurrence is surgical, although interstitial radiotherapy may be appropriate. A check should be made at follow-up for signs of tumour spread to nodes.