6

Disorders of sex development (DSD)

Introduction

Disorders of sex development (DSD) are a group of conditions where the development of chromosomal, gonadal or anatomical sex is atypical. Individuals may present with a blend of male and female characteristics, for example a baby with ambiguous genitalia at birth or an adolescent girl with primary amenorrhoea who on investigation is found to have an XY karyotype. The term ‘DSD’ is a recently adopted classification, which replaces the older terms of ‘intersex, hermaphroditism, pseudohermaphroditism and sex reversal’. This older nomenclature is confusing to clinicians and can be felt as pejorative by patients.

Definitions

The prosaic definition of ‘sex’ is: ‘a species dimorphism, represented at different planes by chromosomes and the genes they carry, gonads, sex ducts, external genitalia, bodily habitus, secondary sex characters and behaviour or psychological attitudes’. ‘Phenotypic sex’ is the apparent sex, judged by external characteristics. Older terms no longer in regular use, include: ‘gonadal sex’, referring to whether there is a testes or ovary present and ‘karyotypic sex’, referring to the chromosome status. ‘Sexual orientation’ refers to the direction of erotic interest, and ‘gender identity’ refers to a person’s self-representation as male or female. Psychosexual development is highly complex and is influenced by many factors, including chromosomes, pre- and postnatal exposure to hormones and brain structure, as well as social influences and family dynamics.

Causes of gender identity disorder or gender dissatisfaction in the absence of atypical sex development are not discussed in this chapter.

Some fundamental principles

1. In the normal fetus, the chromosomal complement of the zygote determines whether the gonad becomes a testis or ovary. The first step in the pathway to a male or female phenotype is dependent on the SRY gene (sex-determining region of the Y chromosome). This gene, helped by other testes-determining genes, causes the gonad to begin development into a testis.

2. Ovarian development was in the past considered a ‘default’ development due solely to the absence of SRY; however, recently, ovarian-determining genes have also been found.

3. All fetuses have Müllerian and Wolffian ducts and the potential to develop male or female internal and external genitalia.

4. This process can go wrong at any stage, leading to the birth of a baby with a DSD.

5. DSD can be diagnosed at birth but can also present at adolescence.

6. All babies should be assigned to a sex of rearing. In the presence of a DSD, this is decided by the parent and a multidisciplinary specialized team. Birth registration can be delayed until agreement is reached.

7. Medical management includes genital surgery to reinforce the chosen sex of rearing, but this is a controversial and topical issue.

Normal sex differentiation

The chromosomes

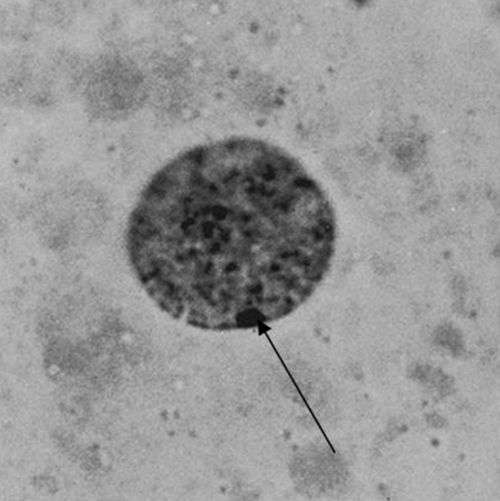

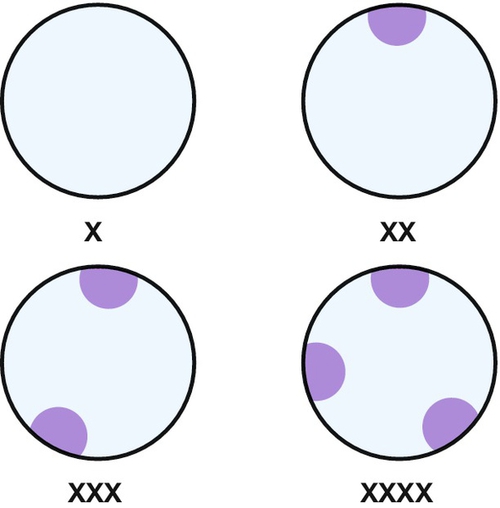

Chromosomal complement is the only sex characteristic of the early conceptus. Central to the accumulation of knowledge of sex chromosome anomalies was the discovery of the nuclear chromatin body, a microscopic blob found under the nuclear membrane of all female cells. It is now clear that one X chromosome is necessary for cell viability, but once ovarian differentiation has been initiated, the second X has no function and condenses to form the Barr body (Fig. 6.1) (see History box). More than two X chromosomes will mean that there are additional bodies – the formula being ‘X chromosomes − 1 = number of Barr bodies’ (see Fig. 6.2).

Fig. 6.2Sex chromatin in relation to X chromosomes.

Barr bodies are peripheral blobs consisting of nuclear chromatin. There is always one less Barr body than the number of X chromosomes.

The Y chromosome

It has long been known that the short arm of the Y chromosome controls testicular development, but identification of the gene has proved a long task. Studies were based on cases in which the gonads and other sex features were contrary to the chromosomes, so-called ‘sex reversal’. It is now clear that a gene called SRY (sex-determining region of Y) is responsible. It encodes a DNA-binding protein, which probably influences other genes to produce differentiation of the primitive gonadal streak into testis. The detail of SRY’s mode of action is now the focus of attention. A very few XX males do not have SRY, so some other genetic material must, in certain circumstances, be able to induce testicular differentiation.

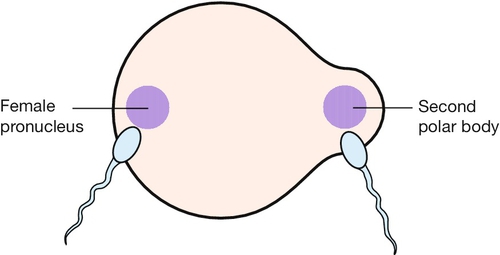

Mixed chromosomes

It is not uncommon for lymphocytes to have mixed sex chromosome complements. This can be due to mosaicism arising from post-fertilization mitotic errors or very rarely, to chimerism, when the cell-mix derives from two separate acts of syngamy (union of gametes). Syngamy may result from dispermic conceptions – one sperm fertilizing the ovum nucleus and another uniting with an unextruded second polar body (see Fig. 6.3) – or from dizygous twins with transfer of tissue soon after conception.

Very rarely, an unextruded second polar body may be fertilized in addition to the haploid ovum nucleus; if the sperms involved are of different sexes, an XX/XY chimera will result.

Genital differentiation

Hormone production by the testes normally determines the phenotypic sex. In a male fetus, Sertoli cells develop and produce anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), which promotes the regression of Müllerian structures. Then, Leydig cells appear and, at around 8 weeks, under the stimulation of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG), start to secrete testosterone. This causes development of the Wolffian structures (the vas deferens, seminal vesicles and epididymis). Peripheral conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone requires the enzyme 5-alpha-reductase and virilizes the external genitalia. At 12 weeks, the fetus is recognizably male and masculinization of the genitalia is said to be complete by 14 weeks. The penis, similar in size to the clitoris at 14 weeks, then enlarges from around 20 weeks, until birth.

In a female fetus, the ovarian cortex develops at 12 weeks and by 13.5 weeks, primordial follicles are present. As AMH is not produced, the Müllerian ducts develop into the uterus, fallopian tubes and upper portion of the vagina. Without androgens, the urogenital sinus develops into the female external genitalia, forming the clitoris, labia and lower vagina. The Wolffian structures regress at around 10 weeks, due to the absence of testosterone. By 15 weeks, the urogenital and Müllerian parts of the vagina meet and fuse and this ‘vaginal plate’ develops a lumen around 20 weeks (see Fig. 2.10).

Incidence of DSD

The incidence of DSD is unknown but current estimates are in the region of 1–2 cases per 1000. For practical purposes, it is enough to realize that one GP can expect to have a dozen or so cases on his or her list, perhaps not all identified; most will be chromosomal. The problems of these conditions, however, are of such complexity and sensitivity that they assume a clinical importance quite disproportionate to incidence or mortality rates.

Classification of DSD

The new DSD terminology, along with previously used terms is listed in Table 6.1. DSD also allows inclusion of conditions such as Turner syndrome and Rokitansky syndrome, where there is a disorder of sex development, which was not previously included in the intersex classification. There is a significant overlap in many of the physical and psychological difficulties experienced by these differing groups of patients and inclusion allows rationalization and improvement of clinical service provision.

Table 6.1

New DSD terminology along with previously used terms

| New terminology | Old terminology |

| Disorders of sex development (DSD) | Intersex |

| 46,XY DSD | Male pseudohermaphrodite Undervirilization of an XY male Undermasculinization of an XY male |

| 46,XX DSD | Female pseudohermaphrodite Overvirilization of an XX female Masculinization of an XX female |

| Ovotesticular DSD | True hermaphrodite |

| 46,XX testicular DSD | XX male or XX sex reversal |

| 46,XY complete gonadal dysgenesis | XY sex reversal |

| Sex chromosome DSD, e.g. Turner syndrome | Sex chromosomal anomalies |

Sex chromosome DSD

Turner syndrome results from a complete or partial absence of one X chromosome. It is the commonest chromosomal anomaly in females, occurring in 1 out of 2500 phenotypic female births. Although there can be variation among affected women, most have clinical features falling into the following three categories:

![]() short stature

short stature

![]() ovarian dysgenesis

ovarian dysgenesis

![]() internal and external dysmorphic features which may be associated with lymphoedema.

internal and external dysmorphic features which may be associated with lymphoedema.

Clinical features associated with Turner syndrome include:

![]() inflammatory bowel disease

inflammatory bowel disease

![]() sensorineural and conduction deafness

sensorineural and conduction deafness

![]() renal anomalies

renal anomalies

![]() cardiovascular disease, both structural (e.g. coarctation) and atherosclerotic

cardiovascular disease, both structural (e.g. coarctation) and atherosclerotic

![]() low bone density

low bone density

![]() endocrine dysfunction, e.g. autoimmune thyroid disease.

endocrine dysfunction, e.g. autoimmune thyroid disease.

The most common chromosome complement in Turner syndrome is monosomy 45,X or the presence of an abnormal X chromosome such as isochromosome X, a partial deletion or a ring X. Mosaicism is also common and includes 45,X/46,XX and 45,X/46,XY. An accurate karyotype is important as it allows some prediction of clinical severity. Ring karyotype is associated with a more severe phenotype, whereas mosaics generally have a milder phenotype with up to 40% entering spontaneous puberty. If there is a Y chromosome, or fragment of a Y present, then there is a higher incidence of gonadal tumours and the streak gonads should be removed prophylactically.

Although the majority of individuals with Turner syndrome are diagnosed during childhood or adolescence, about 10% are not diagnosed until adulthood. The focus of paediatric care is on short stature, whereas adult women are generally more concerned with oestrogen replacement and fertility prospects. Pregnancy is possible, but in general ovum donation is required.

Women with Turner syndrome should be looked after by clinicians experienced in this condition and regular monitoring for associated problems such as deafness and heart disease is essential.

46,XX DSD

The commonest condition in this group is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH). CAH is also the commonest DSD, with an incidence of 1 in 14 000 worldwide. It usually presents with ambiguous genitalia in the neonate.

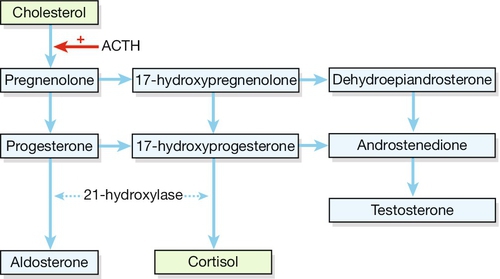

The name is derived from hyperplasia in the adrenal gland, which arises from the overproduction of steroids (Fig. 6.4). Affected individuals have an enzyme block in the steroidogenic pathway in the adrenal gland, with over 90% being a deficiency in 21-hydroxylase; this enzyme converts progesterone to deoxycorticosterone in the aldosterone biosynthetic pathway, and 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) to deoxycortisol in the cortisol biosynthetic pathway. The resultant low levels of cortisol continue to drive the negative feedback loop, leading to increased levels of androgen precursors and, in turn, to elevated testosterone production.

Fig. 6.4Synthesis of steroid hormones.

Deficiency of the enzyme 21-hydroxylase leads to a build-up of precursors, particularly the weak androgens dehydroepiandrosterone and androsterone.

Excessive testosterone levels in a female fetus will lead to virilization of the external genitalia. The clitoris is enlarged and the labia are fused and scrotal in appearance. The upper vagina joins the male-type urethra and opens as one channel onto the perineum. The chromosomes are XX and the ovaries are normal, as are the internal structures, including the fallopian tubes, uterus and upper vagina.

Approximately 75% of children with 21-hydroxylase CAH will have a ‘salt-losing’ variety, which affects the ability to produce aldosterone. This represents a life-threatening situation, and those children who are salt-losing often become dangerously unwell within a few days of birth. Affected individuals require lifelong steroid replacement, such as hydrocortisone, along with fludrocortisone for salt losers. Traditional management comprises feminizing genital surgery during the first year of life to reduce the size of the clitoris and open up the lower vagina. Recent research, however, has confirmed that childhood clitoral surgery can reduce clitoral sensation and is detrimental to adult sexual function. In addition, vaginal surgery usually needs revising at adolescence. This has caused adult patients and some clinicians to question the need for universal feminizing surgery. This issue is hotly debated and further research in this area is ongoing.

CAH is an autosomal recessive condition and molecular genetics now allows prenatal diagnosis in families where an affected child has already been born. Prenatal therapy is possible with dexamethasone, as this crosses the placenta and should therefore reduce the drive mediated by the low cortisol levels. Studies of this are ongoing.

46,XY DSD

Complete androgen insensitivity syndrome (CAIS)

CAIS is the most frequently occurring of this rare group of conditions, with an incidence of 1 in 40 000 to 1 in 90 000 births. Until recently, this condition was called ‘testicular feminization syndrome’; however, this name is both stigmatizing and inaccurate. CAIS is due to an abnormality of the androgen receptor, which is completely or partially unable to respond to androgen stimulation. In a fetus with CAIS, testes form normally due to the action of the SRY gene. At the appropriate time, these testes secrete AMH, leading to the regression of the Müllerian ducts. CAIS women do not therefore have a uterus. Testosterone is also produced at the appropriate time; however, due to the inability of the androgen receptor to respond, the external genitalia do not virilize and instead undergo female development. The result is a female (both physically and psychologically) with no uterus, and testes are found at some point in their line of descent through the abdomen from the pelvis to the inguinal canal. During puberty, breast development will be normal, but the effects of androgens are not seen, and pubic and axillary hair growth is minimal. Around two-thirds of women with CAIS have inherited the androgen receptor gene mutation from their mother (i.e. X-linked inheritance), with the remaining one-third thought to be new mutations.

The commonest presentation is with primary amenorrhoea, although children can also present before puberty with an inguinal hernia found to contain a testis. The diagnosis is made on clinical examination with typical findings in association with an XY karyotype. However, the genetic mutation responsible can be identified in up to 90% and appropriate referral for genetic testing should be considered. Psychological support is the initial mainstay of treatment, with full disclosure of diagnosis, including karyotype, mandatory. In the past, the karyotype was often concealed from the patients, leading to secrecy, stigma and isolation. Well-organized patient peer support groups have a valuable role, but the patient needs to be aware of her diagnosis if she is to access these.

Gonadectomy is usually recommended post-puberty due to the small risk of malignancy associated with intra-abdominal testes. After gonadectomy, oestrogen replacement is necessary to maintain bone density and general well-being. The vagina is blind-ending and usually short. Vaginal self-dilation has good success rates in creating a vagina adequate for intercourse and reconstructive vaginal surgery is rarely required.

Ongoing psychological input from a suitably trained professional who has clinical experience with DSD is a vital part of long-term management.

Partial forms of androgen insensitivity also occur, leading to a spectrum of clinical features. Presentation in this situation is often at birth with ambiguous genitalia, and careful assessment by a specialized team is required to determine the most appropriate sex of rearing.

5-alpha-reductase deficiency

5-alpha-reductase deficiency leads to failure of peripheral conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone. This condition has an autosomal recessive inheritance. Presentation can be with ambiguous genitalia at birth but can also be with increasing virilization at puberty of a female child due to the large increase in circulating testosterone. Clinical management is complex and requires a specialized team. If the child is pubertal, her input into any decision is essential, as is informed consent for any medical or hormonal treatment offered.

Ovotesticular DSD

Ovotesticular states – previously termed true hermaphrodites – involve the presence of ovarian and testicular tissue in the same individual, either as separate gonads or as ‘ovotestes’. The majority of cases have a 46,XX karyotype. Occasionally, an abnormal karyotype is found, but only rarely is this XX/XY – the karyotype which might be expected. It is commoner among the Bantu of South Africa.

As the proportion of ovarian and testicular tissue varies, there is no classical clinical picture. Other forms of DSD have fairly standard clinical patterns and can be confirmed by specific tests: ovotesticular states are suspected by excluding these other diagnoses and are confirmed by histological evidence of both types of gonadal tissue – often a rather major undertaking.

46,XY complete gonadal dysgenesis

This condition is also known as Swyer syndrome. The chromosomes are XY but the gonads are streak gonads and do not function. 10–20% of women with this syndrome have a deletion in the DNA-binding region of the SRY gene. Nevertheless, in approximately 80–90% of cases, the SRY gene is normal and mutations in other testis-determining factors are probably implicated. As the gonads do not become testes, no testosterone or AMH is produced and development is phenotypically female. The external genitalia are unambiguously female at birth and the uterus, vagina and fallopian tubes are normal. The condition usually first becomes apparent in adolescence with delayed puberty and amenorrhoea. A high incidence of gonadoblastoma and germ cell malignancies in the dysgenetic gonad has been reported, and current practice is to proceed to a gonadectomy once the diagnosis is made. Management is otherwise in-line with other cases of ovarian failure and involves induction of puberty with oestrogen in order to develop secondary sexual characteristics and long-term combined replacement therapy with oestrogen and progesterone. Pregnancy is possible with a donated egg.

Summary

DSD may present at birth with ambiguous genitalia in conditions such as CAH and partial androgen insensitivity syndrome. Presentation can also occur at adolescence with primary amenorrhoea or failure to go into puberty in conditions such as CAIS and gonadal dysgenesis. More rarely, presentation is with virilization at puberty with 5-alpha-reductase deficiency.

In all such cases management should be by a multidisciplinary team, the key members of which are an endocrinologist, psychologist and surgeon. For children, the surgeon is most commonly a paediatric urologist; at adolescence, a gynaecologist may also become involved. Careful clinical assessment is essential, and is supported by specialist imaging as well as biochemical and genetic investigation. For newborns with DSD, the decision must be taken as to the most appropriate sex of rearing. Factors taken into consideration will include diagnosis, clinical findings, future fertility potential, and the opinions of the family. If the diagnosis is made later in childhood or at adolescence, the sex of rearing is already determined and is not usually reassigned. The diagnosis of CAH in a neonate is a medical emergency due to the risk of a salt-losing crisis. However, the allocation of sex of rearing should not be rushed into and, as noted above, birth registration can be deferred until an agreed decision has been made.

Management and prospects

The most controversial aspect of management is the role of feminizing genital surgery in children with ambiguous genitalia assigned to a female sex of rearing. Parents can be more worried about the immediate appearance and find it more difficult to look at the long-term issues. It is important that parents and clinicians are aware of the impact on future sexual function when making a decision about irreversible genital surgery for their child.