Chapter 18 Disorders of Phagocyte Function

Clinical Approach to Patients With Disorders of Phagocyte Function

Index of Suspicion

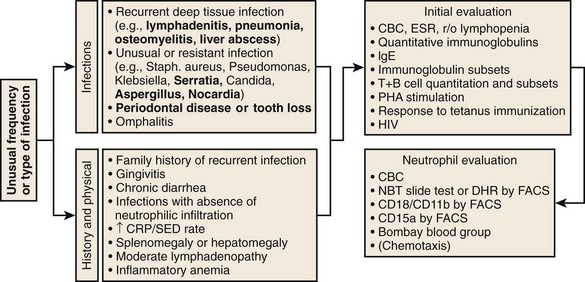

Specific features that may suggest a phagocytic defect are shown in Figure 18-2. Excellent discussions of this problem have been published (see Kyono and Coates1 and Dinauer and Newburger2). Four aspects of each patient’s infection history should be considered: frequency, severity, location, and responsible pathogen. Patients with unusual features in at least one of these aspects should alert the clinician to a possible underlying phagocyte disorder. When considering frequency, the patient’s age and associated medical conditions must be taken into account. For example, recurrent otitis media in a 2-year-old patient is far less worrisome than a similar history in a 40-year-old patient. The more unusual or severe the infections, the less frequently these have to occur before a phagocyte evaluation is indicated. Infections in unexpected anatomic locations, such as hepatic, pulmonary, and rectal abscesses, may indicate an underlying phagocyte defect. Childhood periodontal disease or gingivitis is distinctly uncommon, and in the absence of neutropenic conditions, strongly suggests underlying neutrophil dysfunction. The identification of certain pathogens (e.g., Serratia marcescens, Klebsiella spp., Aspergillus spp., Nocardia spp., Burkholderia cepacia, invasive candidiasis) in children and young adults can provide the strongest indications for pursuing further studies. A history of delayed separation of the umbilical cord is often mentioned as a sign of phagocytic defect. This is fairly common as an isolated finding and is usually of no significance. However, this is in conjunction with omphalitis or other pyogenic infections raises the possibility of LAD or chemotactic defects. A child with nystagmus, fair skin, and recurrent staphylococcal infections should be evaluated for CHS.

Evaluation

Performing a good history and physical examination to eliminate common causes of recurrent infection is important before looking for rare syndromes. For example, is the recurrent pneumonia caused by an aspirated foreign body in the bronchus? In general, patients should first be evaluated for lymphocyte or complement defects. A useful algorithm is presented in Figure 18-2. Note that testing described in this algorithm is not exhaustive, and patients with truly striking histories of unusual kinds of infections should be referred for further evaluation by specialized research laboratories.

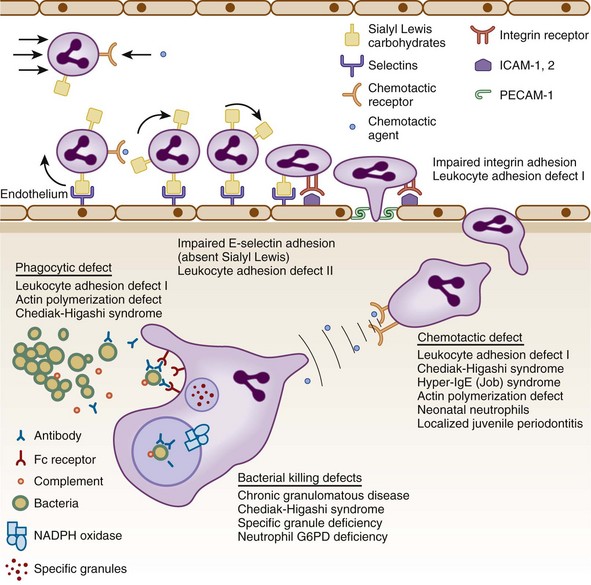

Figure 18-1 STEPS IN THE RESPONSE OF CIRCULATION NEUTROPHILS TO INFECTION.

(Modified from Kyoto W, Coates TD: A practical approach to neutrophil disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am 49:929, 2002, with permission.)

Diagnosis of Chronic Granulomatous Disease

NBT Slide Test

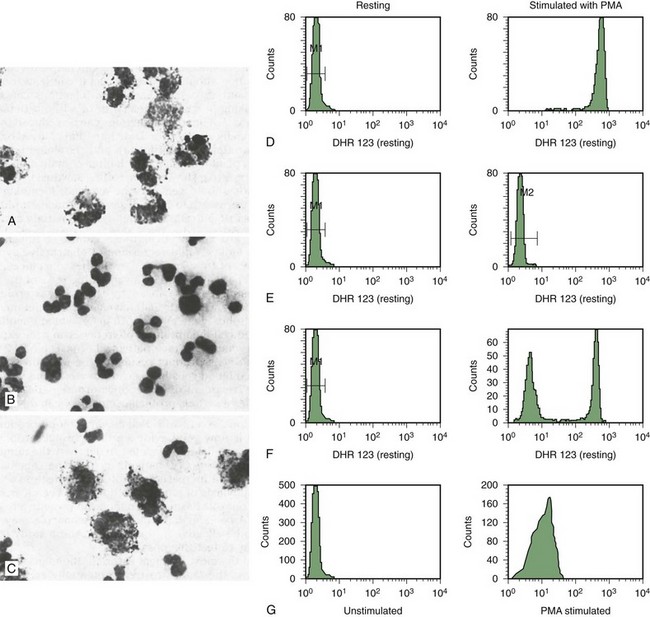

• No NBT reduction (absence of cells with dark blue formazan deposits) in both X-linked and AR forms of CGD (see Fig. 18-3, B).

• Usually no reduction in 50% of cells and normal in 50% for X-linked carrier. The percent positive cells can vary if there is unequal X inactivation and may appear normal or like CGD with extreme lyonization (see Fig. 18-3, C).

• False-positive results can occur (i.e., apparent failure to reduce NBT supporting the diagnosis of CGD) if the neutrophils do not adhere to the slide. This happens with greasy slides or with some cases of LAD. Using PMA to stimulate the cells will avoid this.

DHR Flow Cytometry

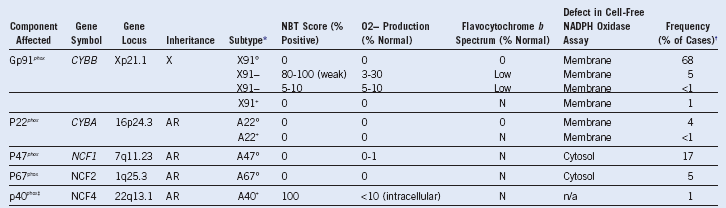

• This approach has replaced the NBT slide test in many laboratories. It has the advantage of assessing large numbers of cells and can give quantitation of the amount of oxidant production.

• The change in fluorescence channel number with stimulation is the critical number and not the percent positive cells.

• X-linked CGD patients will not respond at all and show no increase in fluorescence with stimulation (see Fig. 18-3, F).

• X-linked carriers will show about 50% of the cells that respond with a normal increase in fluorescence, and the other half will have no response. Degrees of unequal X inactivation are much more accurately quantified by this assay (see Fig. 18-3, G).

• AR patients, particularly those with absent p47phox, have some response to stimulation and show a small increase in fluorescence (see Fig. 18-3, H). This level of oxidant production is usually not visible on the NBT test.

• AR carriers have a good response, but the histogram may be broader than normal and may even appear bimodal with a weakly fluorescent peak and a strongly fluorescent peak. This is not distinguishable on the NBT slide test.

• Falsely negative results not supporting the diagnosis of CGD have been reported in specimens that have been run a few days after phlebotomy.

• Falsely abnormal results suggesting CGD can be seen in patients with MPO deficiency because MPO is required to generate strong DHR fluorescence.

Genetic Analysis

• Genetic analysis for X-linked and AR CGD is clinically available and should be performed on at least the proband in each kindred.

Figure 18-3 ANALYSIS OF NEUTROPHIL NICOTINAMIDE ADENINE DINUCLEOTIDE PHOSPHATE (NADPH) OXIDASE ACTIVITY FOR THE DIAGNOSIS OF CHRONIC GRANULOMATOUS DISEASE (CGD).

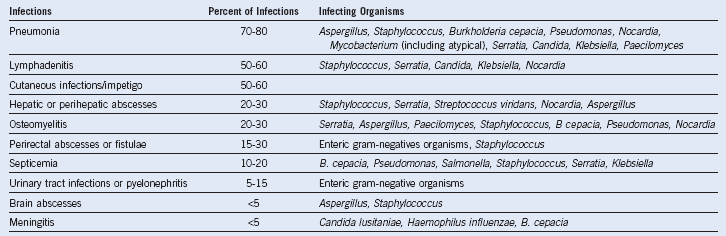

Table 18-1 Classification of Chronic Granulomatous Disease

AR (or A), Autosomal recessive inheritance; N, normal; NADPH, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate; NBT, nitroblue tetrazolium; X, X-linked inheritance.

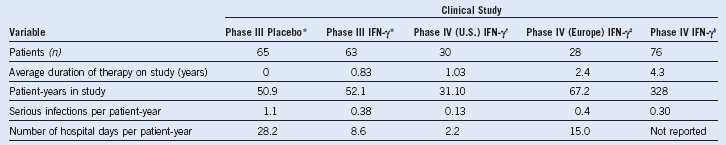

Table 18-2 Infections in Chronic Granulomatous Disease

The relative frequencies of different types of infections in chronic granulomatous disease are estimated from data pooled from several large series of patients in the United States, Europe, and Japan: (1) Mouy R, Fischer A, Vilmer E, et al: Incidence, severity, and prevention of infections in chronic granulomatous disease. J Pediatr 114:555, 1989; (2) Bemiller LS, Roberts DH, Starko KM, et al: Safety and effectiveness of long-term interferon gamma therapy in patients with chronic granulomatous disease. Blood Cells Mol Dis 21:239, 1995; (3) Forrest CB, Forehand JR, Axtell RA, et al: Clinical features and current management of chronic granulomatous disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2:253, 1988; (4) Hitzig WH, Seger RA: Chronic granulomatous disease, a heterogeneous syndrome. Hum Genet 64:207, 1983; (5) Tauber AI, Borregaard N, Simons E, et al: Chronic granulomatous disease: A syndrome of phagocyte oxidase deficiencies. Medicine (Baltimore) 62:286, 1983; (6) Cohen MS, Isturiz RE, Malech HL, et al: Fungal infection in chronic granulomatous disease. The importance of the phagocyte in defense against fungi. Am J Med 71:59, 1981; (7) Hayakawa H, Kobayashi N, Yata J: Chronic granulomatous disease in Japan: A summary of the clinical features of 84 registered patients. Acta Paediatr Jpn 27:501, 1985; and (8) Johnston RB, Newman SL. Chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatr Clin North Am 24:365, 1977. These series encompass approximately 550 patients with CGD after accounting for overlap between reports. Unpublished data from the United States CGD Registry encompassing 368 patients was also used to estimate the relative frequencies of infections and the responsible organisms. The infecting organisms are arranged in approximate order of frequency for each type of infection. Note: B. cepacia was previously classified as Pseudomonas cepacia.

Table 18-3 Chronic Conditions Associated With Chronic Granulomatous Disease*

| Condition | Relative Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Lymphadenopathy | 98 |

| Hypergammaglobulinemia | 60-90 |

| Hepatomegaly | 50-90 |

| Splenomegaly | 60-80 |

| Anemia of chronic disease | Common† |

| Underweight | 70 |

| Chronic diarrhea | 20-60 |

| Short stature | 50 |

| Gingivitis | 50 |

| Dermatitis | 35 |

| Hydronephrosis | 10-25 |

| Granulomatous ileocolitis | 10-15 |

| Gastric antral narrowing | 10-15 |

| Ulcerative stomatitis | 5-15 |

| Granulomatous cystitis | 5-10† |

| Pulmonary fibrosis | <10† |

| Esophagitis | <10† |

| Granulomatous cystitis | <10 |

| Chorioretinitis | <10 |

| Glomerulonephritis | <10 |

| Discoid lupus erythematosus | <10 |

*The relative frequencies of chronic conditions associated with chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) were estimated from the series of reports listed in Table 18-2.

†The incidence is estimated from the 50 cases of CGD followed at Scripps Research Institute and Stanford University (unpublished data).

Diagnosis of Chemotactic Disorders

LAD-1

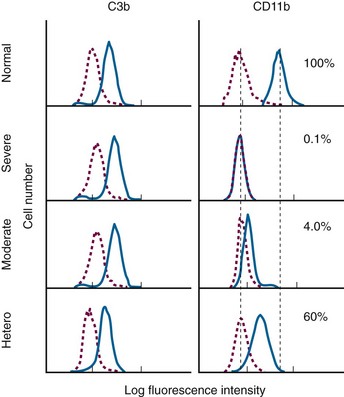

• LAD-1 has a significant chemotactic defect as well as phagocytic defect and is characterized by leukocytosis. The diagnosis can be made by flow cytometry of the CD11b complex on the surface.

• Fig. 18-4 indicates surface expression of C3b and CD11b on neutrophils. C3b is used as a positive control and is normal in LAD1. With stimulation, CD11b increases (top panel)

Figure 18-4 EVALUATION OF ADHESION MOLECULE EXPRESSION FOR DIAGNOSIS OF LEUKOCYTE ADHESION DEFICIENCY (LAD).

.

• The results in this assay are expressed as percent of normal stimulated control mean channel number. It is important to note that this is not the percent positive cell, as is the case for most flow cytometry assays.

• Severe LAD1 has no increase with stimulation.

• Moderate LAD1 shows some shift of fluorescence with stimulation.

• Genetic analysis for this disorder is clinically available.

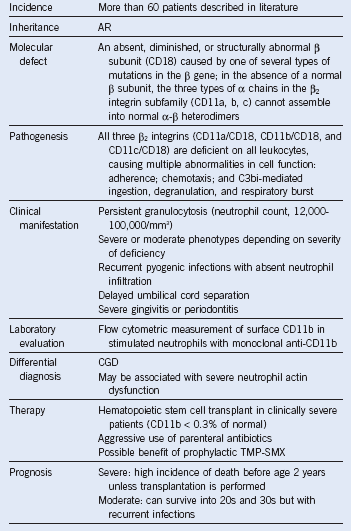

Table 18-5 Summary of Leukocyte Adhesion Deficiency Type 1

AR, Autosomal recessive; CGD, chronic granulomatous disease; TMP-SMX, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.

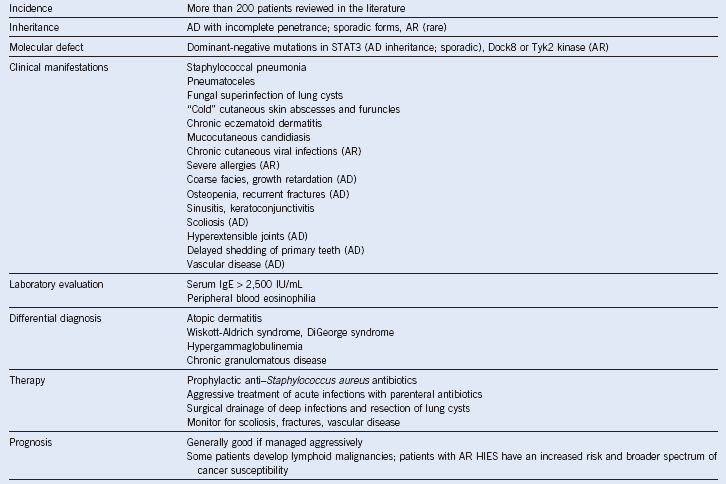

Table 18-6 Summary of Hyperimmunoglobulin E Syndrome

AD, Autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; HIES, hyperimmunoglobulin E syndrome; IgE, immunoglobulin E.

Management of Infections

• Patients tend to present with relatively low fevers and chronic inflammatory processes associated with marked elevation of ESR and CRP. Unless they have untreated abscesses or inflammatory masses, they tend not to present with frank sepsis and positive blood cultures.

• The frequency of infections decreases somewhat with age in children as their normal T and B cell-mediated immunity develops.

• Although one should always attempt to obtain culture proof of an infection, more often than not, it is not possible to identify an organism, and it is necessary to treat empirically.

• Because these patients tend to develop deep seated tissue infections, the ESR can be of great value even though it is quite nonspecific. Elevation in the ESR suggests deep tissue inflammation; CRP is more acute and suggests monocyte activation. Persistent significant elevation of the ESR (>15-20 mm/hr) even in the absence of fever or other symptoms may warrant radiologic search for deep-seated infection.

• The authors advocate an “antibiotic sensitivity by ESR response” approach to empiric therapy in stable patients. One can start at parenteral anti-staphylococcus and gram-negative therapy and monitor the ESR daily. A monotonic decrease in the ESR within several days that is clear-cut suggests the process is sensitive to the antibiotic selected. Although complete resolution of inflammatory response may take many weeks, usually there is some clear change in the ESR within 1 week. If there is worsening or no clear response, then an antifungal can be added and the ESR monitored in the same fashion. Return of an elevated ESR can be a sign of development of organism resistance.

• If a patient with CGD is particularly ill appearing or febrile, it is important to make sure that B. cepacia complex bacteria are covered.

• There is no fixed duration of therapy for any infections in these patients. If the infections are not completely extinguished, they will return and will contribute to development of chronic pulmonary and hepatic fibrosis. Parenteral antibiotics or antibiotics that can deliver very high tissue levels should be continued significantly past normalization of the ESR and disappearance of any radiographic evidence of deep tissue infection. This can take many months for some pneumonias and liver abscesses.

• Short pulses of steroids (4-6 days) can be lifesaving, particularly for pulmonary infections in young children with CGD. They reduce airway inflammation and promote drainage.

• Young children are susceptible to infections with routine childhood viruses and infections and tend to do well with standard therapeutic approaches and courses of treatment that are 2 to 3 times longer than the usual recommended course. Again, monitoring with the ESR can be a guide.

• All standard childhood immunizations and influenza vaccinations are strongly recommended. Prophylactic antibiotics may be appropriate.

1 Kyono W, Coates TD. A practical approach to neutrophil disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2002;49:929. viii

2 Dinauer MC, Newburger PE. The phagocyte system and disorders of granulopoiesis and granulocyte function. In: Nathan DG, Orkin SH, Ginsburg D, et al, eds. Nathan and Oski’s Hematology of infancy and childhood. ed 7. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 2009:1109.