Disorders of Hyperpigmentation

Definitions

Approach to Disorders of Hyperpigmentation

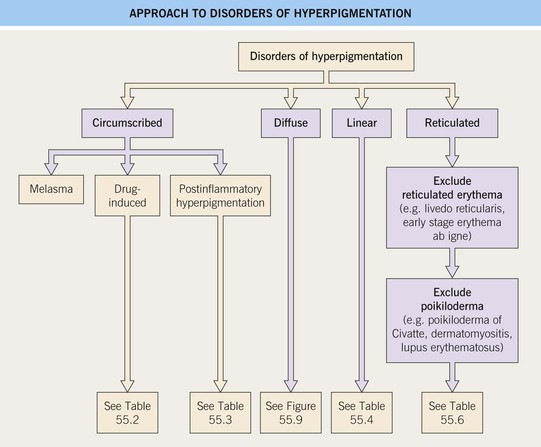

• The clinical approach to these disorders is simplified by dividing them into four patterns, namely circumscribed, diffuse, linear, and reticulated (Fig. 55.1).

Circumscribed Hyperpigmentation

Melasma

• Seen primarily in women; increased prevalence in individuals with skin phototypes III–IV.

• Three classic clinical patterns based on distribution: centrofacial (most common), malar, and mandibular (Fig. 55.2).

Fig. 55.2 Various forms of melasma and melasma-like hyperpigmentation. A Malar variant. B Mild centrofacial type with sparing of the philtrum. C Extension of the hyperpigmentation onto the mandible. D Involvement of the extensor forearm; note the same irregular outline as seen on the face. E Melasma-like appearance in a patient with previous acute cutaneous lupus erythematosus. C–E, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• DDx: postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, drug-induced (e.g. minocycline, amiodarone), acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules (especially in Asian women), actinic lichen planus, pigmented contact dermatitis, exogenous ochronosis due to the application of hydroquinone-containing bleaching agents, erythromelanosis faciei.

• Treatment options are outlined in Table 55.1; typically epidermal hyperpigmentation responds best to treatment.

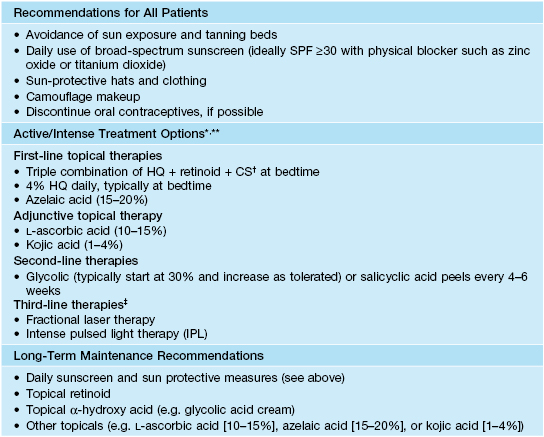

Table 55.1

Suggested treatment options for melasma.

* Results from topical treatments may take up to 6 months to appreciate; depending on the patient, HQ and combination HQ + retinoid + CS are typically used daily for 2–4 months and then decreased in frequency to 1–2 times per week; prolonged daily use can result in side effects such as perioral dermatitis, telangiectasias, and atrophy (CS) and ochronosis (HQ).

** While topical HQ can cause an allergic contact dermatitis, all topical agents may cause an irritant contact dermatitis, which can result in worsening of the dyspigmentation; if this is a concern, a small, nonfacial site test can be performed prior to widespread facial application.

† Typically a Class 5–7 topical CS is used (see Appendix).

‡ Potential risk of post-procedural dyspigmentation; a site test should be performed prior to widespread facial laser or light therapy.

HQ, hydroquinone.

Drug-Induced Circumscribed Hyperpigmentation and Discoloration

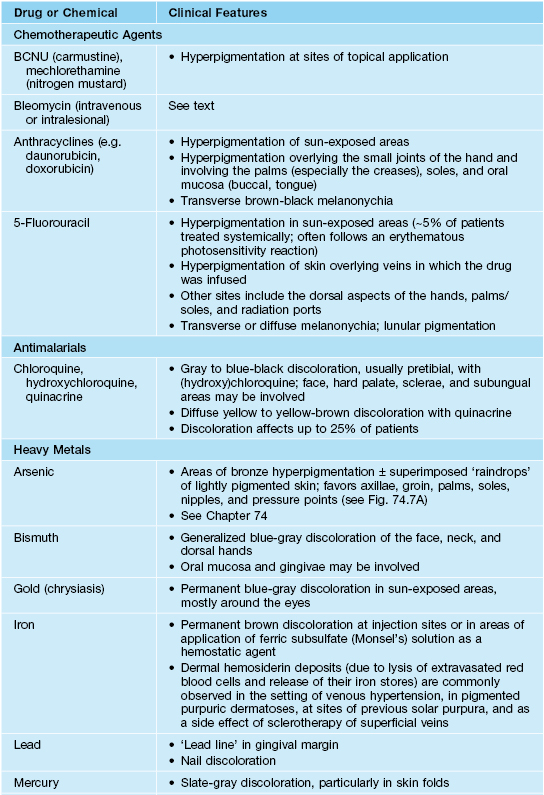

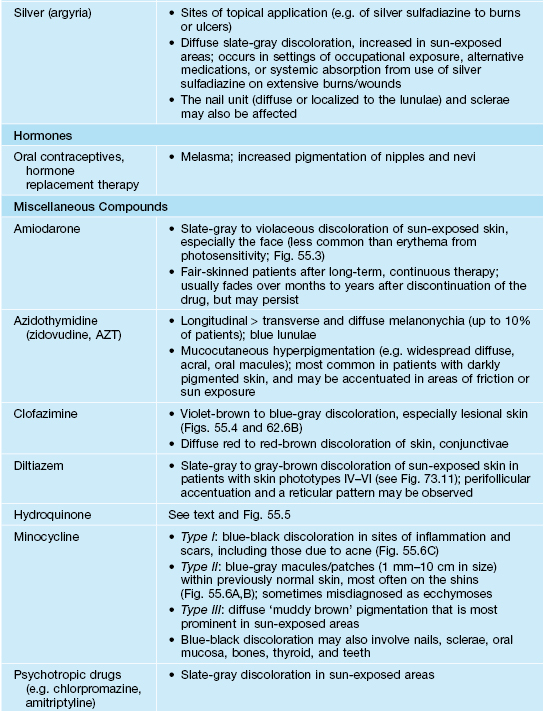

• The most common culprits of drug-induced circumscribed hyperpigmentation and discoloration are minocycline and the antimalarials (Table 55.2; Figs. 55.3–55.6).

Table 55.2

Drugs and chemicals associated with circumscribed hyperpigmentation or discoloration.

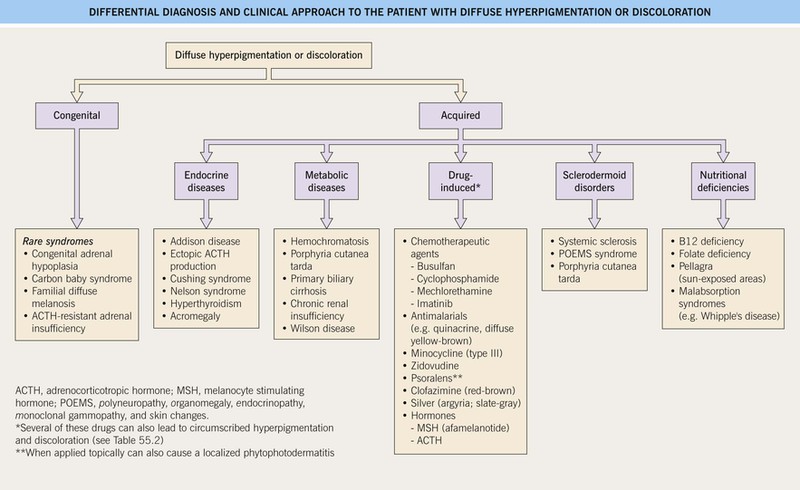

Diffuse hyperpigmentation and discoloration is discussed in Fig. 55.9.

BCNU, 1,3-bis (2-chloroethyl)-1-nitrosourea.

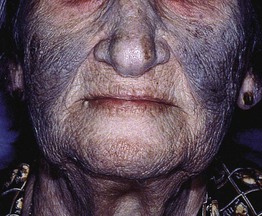

Fig. 55.3 Gray-violet discoloration of the face due to amiodarone. Note the sparing of the lower eyelid. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 55.4 Blue-violet discoloration of previous leprosy lesions in a patient treated with clofazimine. Courtesy, Anne Burdick, MD.

Fig. 55.5 Exogenous ochronosis secondary to topical hydroquinone. This cause of progressive darkening is seen more commonly in Africa. Courtesy, Regional Dermatology Training Centre, Moshi, Tanzania.

Fig. 55.6 Minocycline-induced discoloration. A The distribution on the shins and the gray-blue color can be similar to that seen with antimalarials. B Sometimes the discoloration is misdiagnosed as ecchymoses, but the subsequent color changes of green and yellow do not occur. C Blue-black pigmentation within acne scars and inflammatory papules. A, Courtesy, Mary Wu Chang, MD; C, Courtesy, Richard Antaya, MD.

Postinflammatory Hyperpigmentation

• Depending on the disorder, postinflammatory hypopigmentation may also occur and is discussed in Chapter 54.

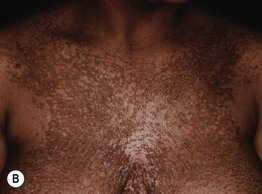

• The preceding inflammation may be obvious, transient, or subclinical (Table 55.3; Fig. 55.7).

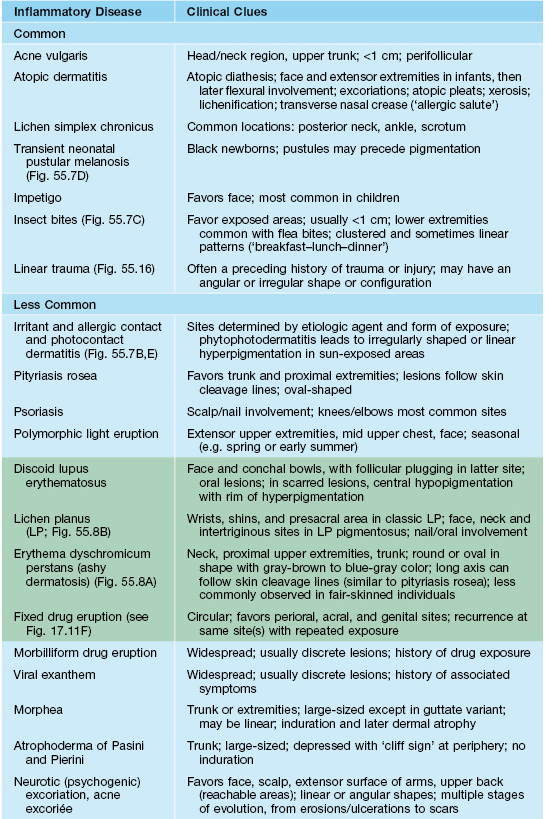

Table 55.3

Disorders associated with postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

Disorders with a green background are characterized by inflammation at the dermal–epidermal junction. Such inflammation can lead to dermal melanin within melanophages (pigment incontinence), which can be resistant to treatment and take longer to resolve. Most disorders result in epidermal hyperpigmentation and eventually resolve if the underlying disorder is treated effectively.

Adapted from Bolognia JL. Disorders of hypopigmentation and hyperpigmentation. In: Harper J, Oranje A, Prose N (Eds.), Textbook of Pediatric Dermatology, 2nd edn. Oxford: Blackwell Science, 2006;997–1040.

Fig. 55.7 Epidermal postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. The lesions were due to pemphigus foliaceus (A), contact dermatitis from a contraceptive patch (B), insect bites (C), and transient neonatal pustular melanosis (D). Note the residual inflammation and ‘breakfast–lunch–dinner’ configuration in (C). E Linear epidermal postinflammatory hyperpigmentation due to phytophotodermatitis, which requires contact with a plant (e.g. lime) containing a photosensitizing chemical followed by UVR exposure. The desquamation is at the site of a previous bulla. A, C, D, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; B, Courtesy, Andrew Alexis, MD, MPH.

• The hyperpigmented macules and patches can range in color from light brown to dark brown (epidermal melanin) or gray-blue to gray-brown (dermal melanin).

• May also be exacerbated by UVR exposure, and photoprotection is an important part of treatment.

• DDx: see Table 55.3; occasionally a skin biopsy will assist in establishing the diagnosis.

• Causes of postinflammatory hyperpigmentation that often present without obvious prior inflammation.

– Primary (localized) cutaneous amyloidosis (see Chapter 39 and Figs. 39.6 and 39.7).

– Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP or ashy dermatosis) (see Chapter 9 and Figs. 9.9 and 55.8A).

Fig. 55.8 Dermal postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. A Erythema dyschromicum perstans (EDP or ashy dermatosis). Multiple gray-brown macules and patches on the abdomen. The ‘ashy’ color is characteristic. B Lichen planus pigmentosus. Multiple coalescing brown to gray-brown macules in the axilla of a middle-aged woman.

– Lichen planus pigmentosus (LPP) (see Chapter 9, Table 9.1, and Figs. 9.4G and 55.8B).

– Mastocytosis (see Chapter 96 and Fig. 96.4).

– Tinea (pityriasis) versicolor (see Chapters 54 and 64 and Fig. 64.1).

– Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (see Chapter 36).

Diffuse Hyperpigmentation

Linear Hyperpigmentation

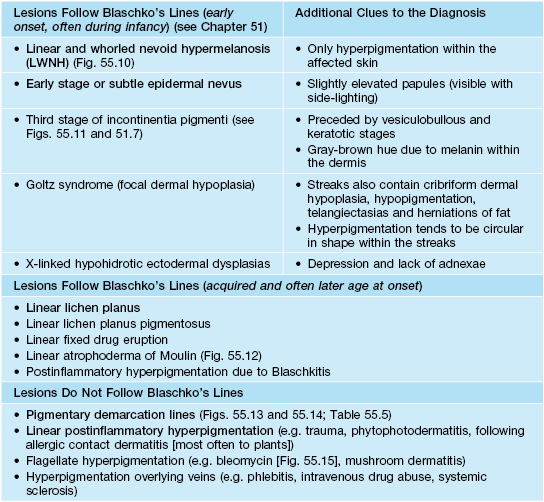

• Linear hyperpigmentation, like linear hypopigmentation (see Chapter 54), can result from multiple etiologies; one of the initial steps is determining if the lesions do or do not follow Blaschko’s lines (see Chapter 51).

• The differential diagnosis of linear hyperpigmentation is presented in Table 55.4 (Figs. 55.10–55.16).

Fig. 55.10 Linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis (LWNH) on the trunk. This young African-American girl had developmental delay. Note the distribution along the lines of Blaschko. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 55.11 Stage 3 incontinentia pigmenti in a 2-year-old child. Note the characteristic gray-brown color, and the distribution along the lines of Blaschko. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 55.12 Linear hyperpigmentation due to atrophoderma of Moulin. Note the subtle depression of the lesions on the upper lateral thigh. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

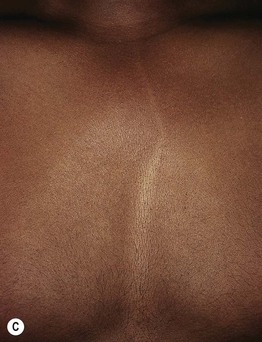

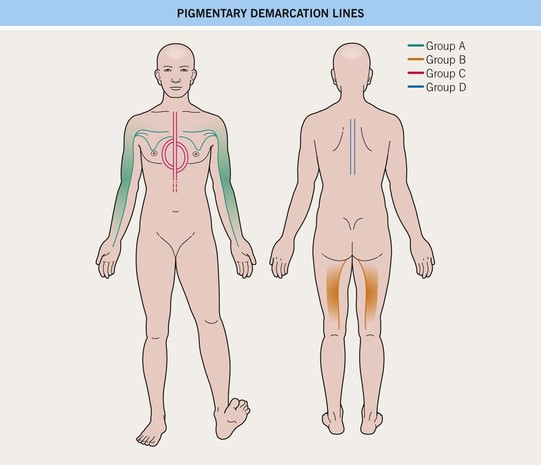

Fig. 55.13 Pigmentary demarcation lines (PDLs). A The most common PDL (Type A) is on the upper arm, with relative hypopigmentation on the ventral surface. B Type B PDLs on the posterior thighs, with relative hypopigmentation medially. C Type C PDL (composed of parallel lines) may be confused with hypopigmentation along Blaschko’s lines. A, C, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Justin Finch, MD.

Fig. 55.14 Pigmentary demarcation lines.

Fig. 55.15 Flagellate pigmentation. This young man had received bleomycin as a treatment for his lymphoma. Note the linear excoriations. Courtesy, David E. Cohen, MD, MPH.

Hyperpigmentation Along Blaschko’s Lines and in Other Mosaic Patterns

• Hyperpigmentation can follow the lines of Blaschko or have other mosaic patterns (e.g. block-like [see Chapter 51]).

• Hyperpigmented streaks along Blaschko’s lines has been termed ‘linear and whorled nevoid hypermelanosis’ (LWNH) or linear nevoid hyperpigmentation, and they reflect pigmentary mosaicism (Fig. 55.10).

• In a minority of patients, LWNH is associated with systemic abnormalities (e.g. CNS, musculoskeletal, or ocular); hyperpigmented streaks usually appear in infancy.

• Hyperpigmentation can also occur in a block-like configuration, also referred to as segmental pigmentation disorder; the DDx includes Becker’s nevus and segmental CALM, either isolated or syndromic (e.g. McCune–Albright syndrome [see Table 50.3]); in the latter, the CALM may be more geographic in configuration.

Linear Hyperpigmentation that is Not Along Blaschko’s Lines

• Pigmentary demarcation lines.

– In humans, the dorsal skin surfaces are relatively hyperpigmented compared to the ventral surfaces.

– These demarcation lines are present from infancy and persist throughout life; they are most prevalent on the anterolateral upper arm and posteromedial thigh (Fig. 55.13).

– Several forms of pigmentary demarcation lines exist and are presented in Table 55.5 and Fig. 55.14.

Table 55.5

Five major forms of pigmentary demarcation lines.

| Type | Description |

| A | A vertical line along the anterolateral portion of the upper arm that may extend into the pectoral region (most commonly observed type) |

| B | A curved line on the posteromedial thigh that extends from the perineum to the popliteal fossa and occasionally to the ankle |

| C | A vertical or curved hypopigmented band on the mid chest that results from two parallel pigmentary demarcation lines |

| D | A vertical line in a pre- or paraspinal location |

| E | Bilateral chest markings (hypopigmented macules and patches) in a zone that runs from the mid third of the clavicle to the periareolar skin |

• Flagellate pigmentation from bleomycin.

– Occurs in ~10–20% of patients treated with systemic bleomycin.

– Pathogenesis is not well understood.

– Presents as linear hyperpigmented streaks on the chest, back, and occasionally extremities (Fig. 55.15); typically in a configuration that suggests a relationship to scratching, but attempts to reproduce lesions by scratching have in general been unsuccessful; an erythematous phase, which is typically pink in light-skinned individuals, can precede the hyperpigmentation.

• Flagellate mushroom dermatitis.

– Occurs after eating large amounts of raw or partially cooked shiitake mushrooms.

– A second form occurs in persons who cultivate shiitake mushrooms.

Linear Hyperpigmentation That May or May Not be Along Blaschko’s Lines

• Linear postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

– More common in individuals with darkly pigmented skin.

– Occurs after linear trauma (e.g. burn, abrasion, dermatitis artefacta [Fig. 55.16]) and along veins (e.g. phlebitis, intravenous drug abuse, systemic sclerosis); also follows linear inflammatory dermatoses, most often allergic contact dermatitis due to plants (e.g. poison ivy/oak dermatitis) or phytophotodermatitis, which requires both plant exposure and UVR (see Fig. 55.7E).

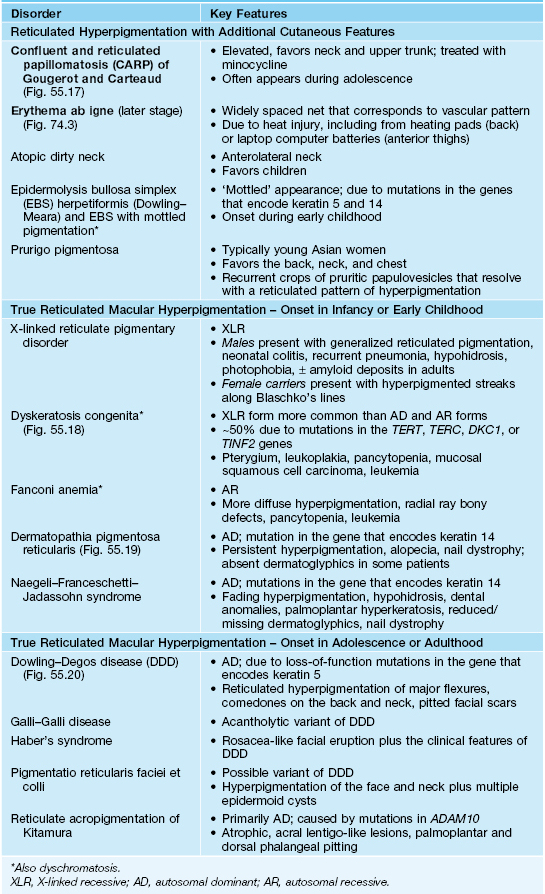

Reticulated Hyperpigmentation

• Disorders characterized by true reticulated macular hyperpigmentation are unusual and are primarily rare genodermatoses (Table 55.6; Figs. 55.17–55.20).

Fig. 55.17 Confluent and reticulated papillomatosis of Gougerot and Carteaud. A On the neck and back of a teenage girl. B On the chest of an older woman. A, Courtesy, Seth Orlow, MD, PhD.

Fig. 55.18 Dyskeratosis congenita. A Reticulated hyperpigmentation on the chest and neck of a teenage boy. B More pronounced reticulated and confluent hyperpigmentation on the shoulder and axilla. C Longitudinal ridging, splitting, and early pterygium formation in another teenage boy. A, Courtesy, Seth Orlow, MD, PhD; B, Courtesy, Eugene Mirrer, MD; C, Courtesy, Anthony Mancini, MD.

Fig. 55.19 Dermatopathia pigmentosa reticularis. Persistent hyperpigmentation in a reticulated pattern extending from the lower abdomen to the thigh in a young man. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Dyschromatoses

• These disorders can be divided into three groups:

– Genetic (e.g. dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria [Fig. 55.21] and dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria [Fig. 55.22]).

Fig. 55.21 Dyschromatosis symmetrica hereditaria. An autosomal dominant disorder characterized by mutations in DSRAD (encodes an adenosine deaminase) and mixed hypo- and hyperpigmentation on the distal hands and feet. Note that the hands are more involved than the forearms. Courtesy, Peter Ehrnstrom, MD.

Fig. 55.22 Dyschromatosis universalis hereditaria. Widespread distribution of both hypo- and hyperpigmented macules. With permission from Urabe K, Hori Y. Dyschromatosis. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:81–85.

– Exposure-induced (e.g. arsenic [see Fig. 74.7A], monobenzyl ether of hydroquinone [MBEH], diphenylcyclopropenone [DPCP], betel leaf).

– Infection-related (e.g. secondary syphilis, pinta [see Chapter 61]).

• There is also a variant of cutaneous amyloidosis that is dyschromic.

For further information see Ch. 67. From Dermatology, Third Edition.