Chapter 654 Disorders of Hair

Hypertrichosis

Hypertrichosis is rare in children and may be localized or generalized and permanent or transient. Hypertrichosis has many causes, some of which are listed in Table 654-1.

Table 654-1 CAUSES OF AND CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH HYPERTRICHOSIS

INTRINSIC FACTORS

Racial and familial forms such as hairy ears, hairy elbows, intraphalangeal hair, or generalized hirsutism

EXTRINSIC FACTORS

Local trauma

Malnutrition

Anorexia nervosa

Long-standing inflammatory dermatoses

Drugs: Diazoxide, phenytoin, corticosteroids, Cortisporin, cyclosporine, androgens, anabolic agents, hexachlorobenzene, minoxidil, psoralens, penicillamine, streptomycin

HAMARTOMAS OR NEVI

Congenital pigmented nevocytic nevus, hair follicle nevus, Becker nevus, congenital smooth muscle hamartoma, fawn-tail nevus associated with diastematomyelia

ENDOCRINE DISORDERS

Virilizing ovarian tumors, Cushing syndrome, acromegaly, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, congenital adrenal hyperplasia, adrenal tumors, gonadal dysgenesis, male pseudohermaphroditism, non–endocrine hormone–secreting tumors, polycystic ovary syndrome

CONGENITAL AND GENETIC DISORDERS

Hypertrichosis lanuginosa, mucopolysaccharidosis, leprechaunism, congenital generalized lipodystrophy, de Lange syndrome, trisomy 18, Rubinstein-Taybi syndrome, Bloom syndrome, congenital hemihypertrophy, gingival fibromatosis with hypertrichosis, Winchester syndrome, lipoatrophic diabetes (Lawrence-Seip syndrome), fetal hydantoin syndrome, fetal alcohol syndrome, congenital erythropoietic or variegate porphyria (sun-exposed areas), porphyria cutanea tarda (sun-exposed areas), Cowden syndrome, Seckel syndrome, Gorlin syndrome, partial trisomy 3q, Ambra syndrome

Hypotrichosis and Alopecia

Some of the disorders associated with hypotrichosis and alopecia are listed in Table 654-2. True alopecia is rarely congenital; it is more often related to an inflammatory dermatosis, mechanical factors, drug ingestion, infection, endocrinopathy, nutritional disturbance, or disturbance of the hair cycle. Any inflammatory condition of the scalp, such as atopic dermatitis or seborrheic dermatitis, if severe enough, may result in partial alopecia; hair growth returns to normal if the underlying condition is treated successfully, unless the hair follicle has been permanently damaged.

Table 654-2 DISORDERS ASSOCIATED WITH ALOPECIA AND HYPOTRICHOSIS

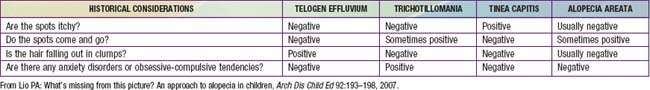

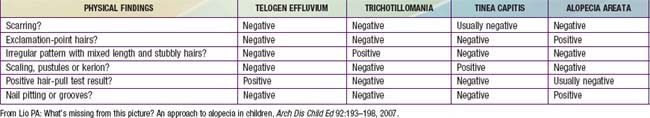

Acquired localized hair loss is the most common type of hair loss seen in childhood. Three conditions—traumatic alopecia, alopecia areata, tinea capitis—are predominantly seen (Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Traumatic Alopecia (Traction Alopecia, Hair Pulling, Trichotillomania)

Traction Alopecia

Traction alopecia is common and is seen in almost 20% of African American schoolgirls. It is due to trauma to hair follicles from tight braids or ponytails, headbands, rubber bands, curlers, or rollers (Fig. 654-1). There is a greater risk of traction alopecia if hair trauma is combined with chemically relaxed hair. Broken hairs and inflammatory follicular papules in circumscribed patches at the scalp margins are characteristic and may be subtended by regional lymphadenopathy. Children and parents must be encouraged to avoid devices that cause trauma to the hair and, if necessary, to alter the hairstyle. Otherwise, scarring of hair follicles may occur.

Hair Pulling

Trichotillomania

Clinical Manifestations

Compulsive pulling, twisting, and breaking of hair produces irregular areas of incomplete hair loss, most often on the crown and in the occipital and parietal areas of the scalp. Occasionally, eyebrows, eyelashes, and body hair are traumatized. Some plaques of alopecia may have a linear outline. The hairs remaining within the areas of loss are of various lengths (Fig. 654-2) and are typically blunt-tipped because of breakage. The scalp usually appears normal, although hemorrhage, crusting (Fig. 654-3), and chronic folliculitis may also occur. Trichophagy, resulting in trichobezoars, may complicate this disorder.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute reactional hair pulling, tinea capitis, and alopecia areata must be considered in the differential diagnosis of trichotillomania (see Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Treatment

Trichotillomania is closely related to obsessive-compulsive disorder and may be an expression of it for some children. When trichotillomania occur secondary to obsessive-compulsive disorder, clomipramine 50-150 mg/day or fluoxetine 40-80 mg/day may be helpful, particularly when combined with behavioral interventions (Chapter 22). N-Acetylcysteine may also be helpful.

Alopecia Areata

Clinical Manifestations

Alopecia areata is characterized by rapid and complete loss of hair in round or oval patches on the scalp (Fig. 654-4) and on other body sites. In alopecia totalis, all the scalp hair is lost (Fig. 654-5); alopecia universalis involves all body and scalp hair. The lifetime incidence of alopecia areata is 0.1% to 0.2% of the population. More than half of affected patients are younger than 20 yr.

The skin within the plaques of hair loss appears normal. Alopecia areata is associated with atopy and with nail changes such as pits (Fig. 654-6), longitudinal striations, and leukonychia. Autoimmune diseases such as Hashimoto thyroiditis, Addison disease, pernicious anemia, ulcerative colitis, myasthenia gravis, collagen vascular diseases, and vitiligo may also be seen. An increased incidence of alopecia areata has been reported in patients with Down syndrome (5-10%).

Differential Diagnosis

Tinea capitis, seborrheic dermatitis, trichotillomania, traumatic alopecia, and lupus erythematosus should be considered in the differential diagnosis of alopecia areata (see Tables 654-3 and 654-4).

Treatment

The course is unpredictable, but spontaneous resolution in 6-12 mo is usual, particularly when relatively small, stable patches of alopecia are present. Recurrences are common. Onset at a young age, extensive or prolonged hair loss, and numerous episodes are usually poor prognostic signs. Alopecia universalis, alopecia totalis, and alopecia ophiasis (Fig. 654-7)—a type of alopecia areata in which hair loss is circumferential—are also less likely to resolve. Therapy is difficult to evaluate because the course is erratic and unpredictable. The use of high- or super-potency topical corticosteroids is effective in some patients. Intradermal injections of steroid (triamcinolone 5 mg/mL) every 4-6 wk may also stimulate hair growth locally, but this mode of treatment is impractical in young children or in patients with extensive hair loss. Systemic corticosteroid therapy (prednisone 1 mg/kg/day) has been associated with good results; the permanence of cure is questionable, however, and the side effects of chronic oral corticosteroids are a serious deterrent. Additional therapies that are sometimes effective include short-contact anthralin, topical minoxidil, and contact sensitization with squaric acid dibutylester or diphencyprone. In general, parents and patients can be reassured that spontaneous remission of alopecia areata usually occurs. New hair growth may initially be of finer caliber and lighter color, but replacement by normal terminal hair can be expected.

Congenital Diffuse Hair Loss

Trichorrhexis Nodosa

Congenital trichorrhexis nodosa is an autosomal dominant condition. The hair is dry, brittle, and lusterless, with irregularly spaced grayish white nodes on the hair shaft. Microscopically, the nodes have the appearance of two interlocking brushes (Fig. 654-8A). The defect results from a fracture of the hair shaft at the nodal points caused by disruption of the cells in the hair cortex. Trichorrhexis nodosa has also been observed in some infants with Menkes syndrome, trichothiodystrophy, citrullinemia, and argininosuccinic aciduria.

Monilethrix

The hair shaft defect known as monilethrix is inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with variable age of onset, severity, and course. Mutations in the hair keratins HBI, HB3, and HB6 have been identified. The hair appears dry, lusterless, and brittle, and it fractures spontaneously or with mild trauma. Eyebrows, lashes, body and pubic hair, and scalp hair may be affected. Monilethrix may be present at birth, but the hair is usually normal at birth and is replaced in the first few months of life by abnormal hairs; the condition is sometimes first apparent in childhood. Follicular papules may appear on the nape of the neck and the occiput and, occasionally, over the entire scalp. Short, fragile beaded hairs that emerge from the horny follicular plugs give a distinctive appearance. Keratosis pilaris and koilonychia of fingernails and toenails may also be present. Microscopically, a distinctive, regular beading pattern of the hair shaft is evident, characterized by elliptic nodes that are separated by narrower internodes (Fig. 654-8B). Not all hairs have nodes, and both normal and beaded hairs may break. Patients should be advised to handle the hair gently to minimize breakage. Treatment is generally ineffective.

Trichorrhexis Invaginata (Bamboo Hair)

Short, sparse, fragile hair without apparent growth is characteristic of trichorrhexis invaginata, which is found primarily in association with Netherton syndrome (Chapter 649). It has also been reported in other ichthyosiform dermatoses. The distal portion of the hair is invaginated into the cuplike proximal portion, forming a fragile nodal swelling (Fig. 654-8C).

Uncombable Hair Syndrome (Spun-Glass Hair)

The hair of patients with uncombable hair syndrome appears disorderly, is often silvery blond (Fig. 654-9), and may break because of repeated, futile efforts to control it. The condition is probably autosomal dominant in inheritance. Eyebrows and eyelashes are normal. A longitudinal depression along the hair shaft is a constant feature, and most hair follicles and shafts are triangular (pili trianguli et canaliculi). The shape of the hair varies along its length, however, preventing the hairs from lying flat.

Bedocs LA, Bruckner AL. Adolescent hair loss. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2008;20:431-435.

Cheng AS, Bayliss SJ. The genetics of hair shaft disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;59:1-22.

Grant JE, Odlaug BL, Kim SW. N-Acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania. Arch Gen Psych. 2009;66(7):756-763.

Harries MJ, Sun J, Paus R, et al. Management of alopecia areata. BMJ. 2010;341:242-246.

Khumalo NP, Jessop S, Gumedze F, et al. Determinants of marginal traction alopecia in African girls and women. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:432-438.

Lio PA. What’s missing from this picture? An approach to alopecia in children. Arch Dis Child Ed. 2007;92:193-198.

Sah DE, Koo J, Price VH. Trichotillomania. Dermatol Ther. 2008;21:13-21.