CHAPTER 20 Disorders and investigation of female reproduction

Epidemiology

Time to conception

A common definition employed in describing infertility is the inability of a couple to conceive following 12–24 months of exposure to pregnancy. The length of exposure time considered is determined by the observation that in the general population, which would include a proportion of couples with infertility, one would expect the chance of conception in any individual cycle to be 20%. Thus, by 1 year of exposure, approximately 85% of couples would have achieved conception, and once 2 years has elapsed, some 92% would have conceived (Evers 2002). Others have evaluated conception rates in truly fertile couples and found that the expectation of pregnancy at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months was 42%, 75%, 88% and 98%, respectively (Gnoth et al 2003). In practical terms, the failure to achieve pregnancy causes enormous distress to those affected. For people with fertility problems, using a definition of 1 year to describe infertility is usual, and most will have sought medical advice or assistance by that time. Natural fertility rates decline in association with increasing female age, although in an ultimately fertile group of women, it is not certain that their monthly fecundability (percentage chance of conception) is any less than younger cohorts. It may be sensible to consider specialist referral of women over 35 years of age in advance of 1 year, although it is acknowledged that, in many instances, conception will occur naturally in these cases since it can be assumed that a proportion will not be infertile.

Prevalence

Estimates of the prevalence of infertility in the population will be influenced by the duration of infertility used in the definition and the population studied. The setting of prevalence studies, such as primary care (Snick et al 1997) or hospital clinics (Hull et al 1985), will influence the prevalence figures. Community-based data, which would give an accurate reflection of prevalence within the general population, are limited. It is not surprising, therefore, that existing studies suggest a range of lifetime prevalence of infertility extending from 6.6% to 32.6%. One population-based study in the North East of Scotland (Templeton et al 1990), which took account of conceptions resulting in miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy, found a prevalence of 14% using a 2-year definition.

A number of factors have been a matter of concern in recent years with respect to their potential impact on the prevalence of infertility, including the incidence of sexually transmitted infection such as Chlamydia trachomatis in the young (Macmillan and Templeton 1999). In addition, there have been suggestions that environmental factors may affect male fertility (Oliva et al 2001), and one should wonder about the possible effects on female fertility of delayed childbearing as determined by changes in lifestyle and working patterns. Despite these legitimate concerns, when the population-based study was repeated (Bhattacharya et al 2009), the observed prevalence of infertility had not increased in North East Scotland in the succeeding 20 years.

A lack of observed change in prevalence should not encourage complacency in respect of public health responsibilities. While opportunities to prevent infertility are limited, encouragement to the young to engage in safe sexual practices, limiting exposure to risk of sexually transmitted infection, is clearly important. For teenage girls, rubella immunization programmes should be in place and human papillomavirus vaccination programmes are now being established. Education of the public about the known decline in fertility which occurs with age, particularly in females over 35 years of age, is also important. In addition, the need for folic acid supplementation for women to reduce the risk of neural tube defects should be promoted, as well as the need to make certain lifestyle adjustments on issues such as the potential need to moderate levels of smoking and alcohol consumption, as well as achieving optimal weight. There is convincing evidence that smoking, active or passive, affects reproductive performance in women and men, as well as increasing the risk of small-for-gestational-age infants, stillbirth and infant mortality (National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health for the National Institute of Clinical Excellence 2004).

The requirement to take account of future reproductive needs in women is essential where abdominal or pelvic surgery is carried out, and careful technique should be employed to minimize the risk of pelvic adhesions. Where uterine instrumentation is considered, particularly in women under 25 years of age, the prevention of Chlamydia infection is receiving appropriate attention (Macmillan and Templeton 1999). Screening tests to detect the organism in first-void urine samples or cervical swabs using nucleic acid amplification techniques should be available routinely, and antibiotic treatment should be given for identified cases and potential contacts. Good lines of communication to sexual health and genitourinary medicine services will facilitate swift management.

Diagnostic categories

The management of people with infertility problems is largely dictated by the major diagnostic category in which they fit. Typical figures are shown in Table 20.1.

Table 20.1 Diagnostic categories and distribution of couples with primary and secondary infertility

| Diagnostic category | Infertility | |

|---|---|---|

| Primary (%) | Secondary (%) | |

| Male factor | 25 | 20 |

| Disorders of ovulation | 20 | 15 |

| Tubal factor | 15 | 40 |

| Endometriosis | 10 | 5 |

| Unexplained | 30 | 20 |

Diagnostic categories in most studies include male factors, disorders of ovulation, tubal factors, endometriosis and unexplained infertility. The distribution of causes, when analysed, will be affected by whether the female has been pregnant in the past (i.e. secondary infertility). This has an association with an increased risk of tubal factor infertility compared with those couples with primary infertility (i.e. where there has not been a pregnancy in the past) (see Chapter 21, Disorders of male reproduction, for more information). The possibility that male factors may contribute to a couple’s infertility should not be ignored, even where the man has fathered a pregnancy in the past. It should be borne in mind that more than one factor may contribute to a couple’s infertility, and each may require simultaneous management; for example, ovulation induction for a woman who is not ovulating, in combination with donor insemination. Decisions to initiate active treatment will be influenced by the age of the female, the duration of infertility, and whether or not there has been a pregnancy in the past. Initiating intrusive and potentially harmful treatment should take account of natural expectations of pregnancy. In many instances, expectant management will be appropriate.

Initial Assessment

Integrated care

Integrated care, by definition, must include the general practitioner (GP), whose role is of fundamental importance (Hamilton 1992). Infertility is a deeply personal problem and many individuals will prefer to discuss intimate matters with someone they know and trust. The counselling support that the GP can provide as preliminary assessment is made and investigations initiated is an excellent foundation for provision of care. Not infrequently, the male and female may be registered with different GPs. This can present difficulties. One should always consider that infertility is a problem affecting both parties, and each may contribute to the pathogenesis. Once referral is made to a specialist clinic, increasing the demands on couples’ time, the intrusive nature of some of the investigations may add to the stress of the situation. Infertility, its investigation and treatment, can threaten domestic stability and it is often the GP, through longstanding knowledge of the couple and their families, who may be in the best position to provide support for those struggling to come to terms with continued disappointment.

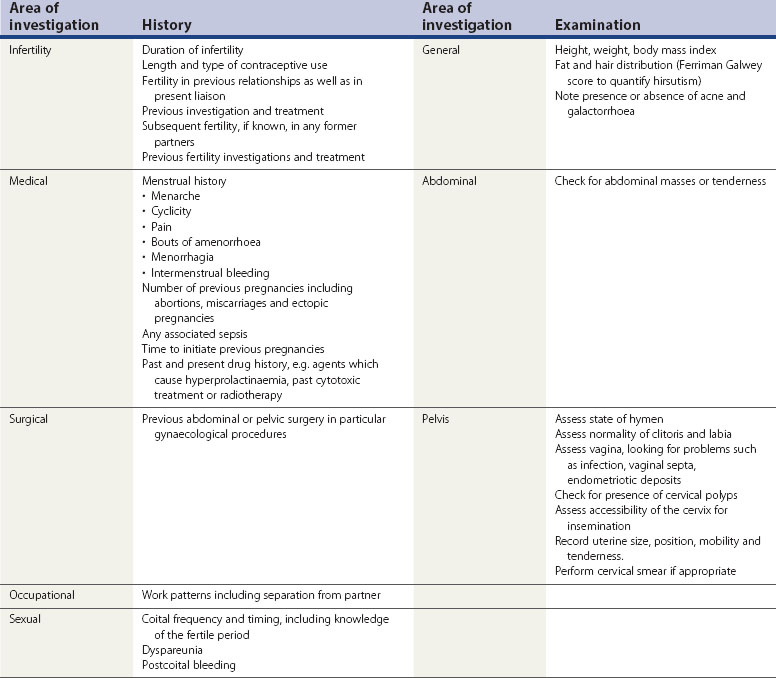

Appropriate Initial Investigations

The principles of investigation of the male will be discussed in detail in Chapter 21. Suffice it to say that semen analysis remains the cornerstone of assessment. In administrative terms, it is helpful if the analysis is done in a dedicated andrology laboratory which serves the fertility clinic, to which onward referral would be made if required.

Disorders of Ovulation

Measurement of serum progesterone

Serum progesterone levels in excess of 30 nmol/l 7 days after ovulation are usually taken as indicative of satisfactory ovulation, although lower levels are not incompatible with egg release and corpus luteum formation (Hull et al 1982, Wathen et al 1984). This is a retrospective measure of ovulation in so far as the peak level of progesterone is found after egg release. It is important to relate progesterone levels to the timing of subsequent menstruation. Samples will typically be checked on day 21 of a 28-day cycle. Serial checks will be required if the cycle is longer than this or is variable in length. Shorter cycle length will require an assessment earlier than day 21. Testing for LH is difficult in practice since the day of the LH surge cannot be predicted in advance with certainty. Urinary kits are available to detect LH and can be helpful in treatment cycles where the timing of artificial insemination is critical. Their use in detecting ovulation in routine investigation is not encouraged.

Ovulation failure

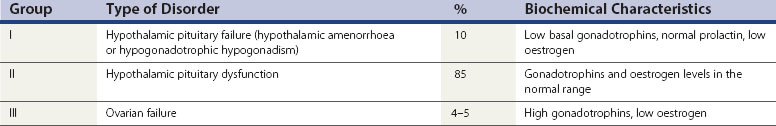

The World Health Organization (WHO) classification of ovulatory dysfunction (Table 20.3) is a helpful system of categorizing disorders of ovulation based on the pathogenesis of the disorder.

The most common ovulation disturbances (WHO Type II) are associated with disordered hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian function. These women will have oestrogen levels in the normal range and many are overweight, presenting with infrequent or absent periods. A common finding is the presence of polycystic ovaries on ultrasound, seen in up to 90% of such cases. In contrast to WHO Type I patients, these women will usually menstruate after exposure to a short course of progestagen treatment. Ultrasound scanning should be timed to coincide with either a natural or progestagen-induced menstrual period. Where there is clinical or biochemical evidence of hyperandrogenism, this, together with menstrual irregularity and ovarian morphology, should be taken into account in reaching a diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). A consensus view on standardized criteria for the diagnosis of PCOS has helped in establishing a uniform approach, and facilitated easier comparison of clinical and research experience in different centres (Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group 2004a, b). It was agreed that the presence of any two of the following triad are sufficient to make the diagnosis: (i) oligo-ovulation and/or anovulation; (ii) polycystic ovaries on ultrasound; and (iii) clinical and/or biochemical hyperandrogenism.

Ovarian failure

In patients presenting with amenorrhoea and where initial biochemical screening and physical examination lead one to suspect ovarian failure (WHO Type III), the presence of a genetic disorder such as Turner’s syndrome (45XO) or Turner mosaic (45XO/46XX) should be considered and a karyotype performed. Occasionally, deletions in one of the X chromosomes or defects in the fragile X gene may lead to ovarian failure, but agenesis of the ovaries (associated with primary amenorrhoea) and premature ovarian failure (presenting as secondary amenorrhoea before 40 years of age) is sometimes found in the presence of a normal karyotype. Acquired ovarian failure may occur as a result of previous medical treatment such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy for cancer. Autoimmune ovarian failure should be considered, and screening for antiovarian antibodies may be useful in reaching a diagnosis. If positive, the need to screen for other autoimmune disorders including hypothyroidism, adrenal insufficiency (Addison’s disease), diabetes mellitus and pernicious anaemia should be considered (see Chapter 17, Ovulation induction, for more information).

Tubal Factor Infertility

X-ray hysterosalpingography

This is an outpatient examination and involves the instillation of either a water- or oil-soluble contrast medium through a cannula attached to the cervix. The fluid, being radio-opaque, can be visualized under X-ray screening conditions. An assessment is made of the normality of the uterine cavity. Passage of dye to the side of the uterus permits an assessment of tubal anatomy (Figure 20.1). The diameter of the tube should be small through its interstitial, isthmic and ampullary portions, but the diameter increases slightly as the infundibulum is reached. Unimpaired passage of dye throughout the length of the tube and dispersal into the peritoneal cavity is suggestive of normal anatomy. If there is impaired flow or localization of spill distally, one should be suspicious of peritubal adhesions. The finding of a hydrosalpinx will be indicative of severe tubal damage. Sometimes, unilateral or bilateral tubal spasm occurs and a mistaken diagnosis of proximal tubal obstruction is made. An intravenous injection of glucagon can help to relax this, but if the finding persists, a cornual block is a possibility. It is important, particularly in women under 25 years of age, to consider the need for antibiotic prophylaxis since Chlamydia infection could be reactivated in susceptible women. Azithromycin or doxycycline is usually used.

The contrast medium used in HSG may contain iodine, and the possibility of allergic reactions should be borne in mind. Significant extravasation of oil-soluble contrast media within the pelvis may lead to lipogranuloma formation. There is some evidence that the use of an oil-soluble contrast medium (lipiodol) may enhance the chance of pregnancy in unexplained infertility (Johnson et al 2004), although it has not gained widespread popularity as a therapeutic choice.

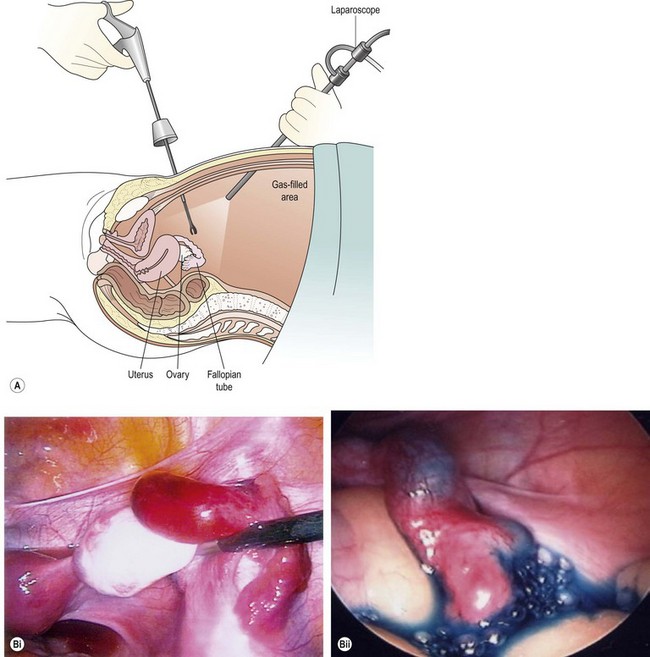

Laparoscopy and dye hydrotubation

It is generally accepted that laparoscopy and dye hydrotubation is the gold standard of tubal assessment. In this procedure, which, like HSG, should avoid the time of menstruation and any chance of pregnancy, a coloured dye is injected through the cervix while carrying out a laparoscopic inspection of the pelvis (Figure 20.2). Failure of dye to pass through the tube is indicative of blockage (Figure 20.3).

Direct visualization of the pelvis permits identification of adhesions, fibroids, endometriosis, ovarian cysts and other pathology which may be relevant to infertility and would be missed at HSG. The likelihood of finding tubal disease is increased if the patient has a positive Chlamydia screening test (Coppus et al 2007). Immediate treatment of pathology is also possible at laparoscopy, which may be particularly relevant where endometriosis is found, provided that appropriate consent has been obtained.

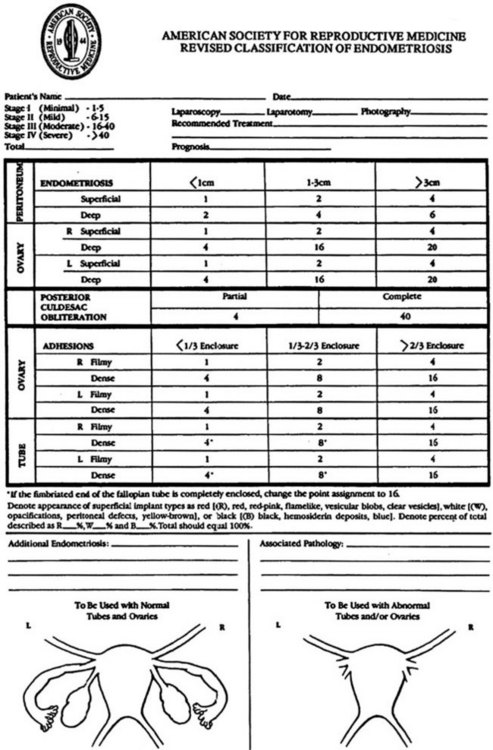

The use of a diagram, such as that produced by the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM), to record findings is often helpful in explaining to patients what has been seen and done, as well as providing a formal record of the findings, particularly if endometriosis is found (Figure 20.4).

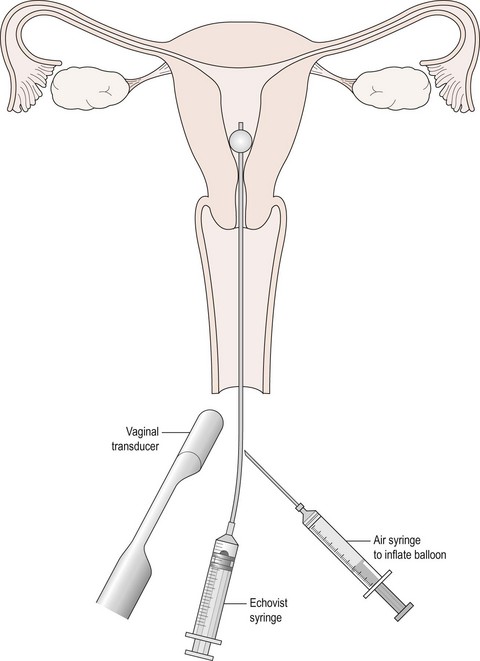

Hysterosalpingo contrast sonography

In the last two decades, HyCoSy has attracted some interest as an additional method for assessing tubal patency (Hamilton et al 1998). Carried out as an outpatient or office procedure, a small balloon catheter is inserted into the uterine cavity through the cervix (Figure 20.5). A vaginal scan is performed while a suspension of an ultrasound contrast agent (Echovist) is injected through the catheter. Usually, only 2–5 ml of fluid will be required. The medium contains galactose granules, and if flow is seen through the length of the tube, it is likely to be patent. Hydrosalpinges can also be identified. Saline alone can be used if inspection of the uterine cavity alone is required, and good imaging of endometrial polyps can be obtained. The technique requires considerable ultrasound skill, and some patients find the instillation of the fluid uncomfortable. There is no evidence of therapeutic benefit through flushing with the medium used in HyCoSy (Lindborg et al 2009).

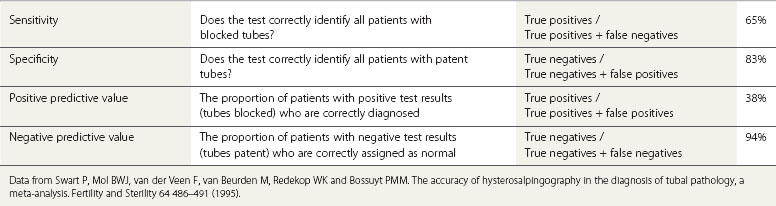

Evaluation of diagnostic tests of tubal factor infertility

With HSG, one is interested to know whether the test identifies normal and abnormal tubes correctly compared with the gold standard, laparoscopy. The value of a test for tubal blockage (test positive) can therefore be described using a number of statistical descriptors, as shown in Table 20.4.

A meta-analysis evaluating HSG assessment of tubal patency using laparoscopy as the gold standard showed 65% sensitivity and 83% specificity (Swart et al 1995, Mol et al 1996). One can deduce from this that although HSG is of limited value in detecting tubal blockage because of its low sensitivity, its high specificity makes it a better test for identification of tubal patency. The negative predictive value (94%) of the test as a predictor of tubal patency is also high, suggesting that the finding of normal tubes on HSG is likely to be correct. However, a low positive predictive value of 38% of the test suggests that HSG is not a reliable indicator of tubal occlusion, and in the circumstances of an abnormal HSG result, it would be wise to consider a laparoscopic assessment to confirm or refute the findings (National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health for the National Institute of Clinical Excellence 2004).

HyCoSy also performs fairly well in detecting normality and hydrosalpinx formation; however, similar to HSG, it is less reliable in identifying tubal blockage (Hamilton et al 1998).

Endoscopic assessment of the tubal lumen to study mucosal appearance has not proved to be helpful in routine work-up of infertility. Falloposcopy achieves access to the tube per vaginam (Rimbach et al 2001). Salpingoscopy can be performed at laparoscopy or laparotomy where the tube is cannulated through the fimbria (de Bruyne et al 1997). Initially thought to be of potential use in selecting patients with healthy tubal epithelium who might be suitable for tubal surgery, neither of the techniques has gained much popularity and they are rarely used.

Endometriosis, Fibroids and Uterine Factors

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is a debilitating condition which has associations with infertility, particularly where there is anatomical distortion of the pelvis. Women who are susceptible to the condition may have genetic, immunological, hormonal or environmental factors contributing to the problem (Crosignani et al 2006). A family history of the condition should alert the gynaecologist to the possibility, particularly if the common symptoms of dysmenorrhoea and chronic pelvic pain are present. Pelvic examination may reveal a fixed, tender retroverted uterus, and on occasions, there may be endometriotic nodules presenting the vault of the vagina or the rectovaginal septum. A combined rectal and vaginal examination may be helpful if this is suspected. Laparoscopic visualization of endometriotic lesions is the cornerstone of diagnosis, although a histological confirmation of an excised lesion is strictly necessary to be absolutely certain. The accuracy of the diagnosis therefore depends on the degree of skill and vigilance of the surgeon. If endometriosis is found at laparoscopy, it is helpful to stage the disease by reference to the ASRM guidelines (American Society for Reproductive Medicine 1996). There is some evidence that women with mild endometriosis have reduced fertility (Akande et al 2004), and that treatment, such as with diathermy, may improve the natural chances of conception in minimal/mild disease (Marcoux et al 1997). A suspicion of endometriosis may be raised if vaginal ultrasound examination of the pelvis is painful, or if a cyst with a hazy ‘ground glass’ appearance is seen in the ovary, suggestive of an endometrioma. Magnetic resonance imaging of the uterus may be helpful if one suspects adenomyosis. Biochemical assay of CA125, if raised, may be suggestive of endometriosis, although this is non-specific. Women with Müllerian abnormalities promoting retrograde menstruation are at greater risk of developing endometriosis.

Fibroids

Fibroids are among the most common benign tumours in women, with a reported prevalence of 3–8% in unselected women of reproductive age (Borgfeldt and Andolf 2000), although they occur with higher frequency in older women and in certain ethnic populations. Fibroids are often asymptomatic but an association with infertility is possible (Somigliana et al 2007), particularly where the tumour impinges on the cavity of the uterus (Khalaf et al 2006, Klatsky et al 2007). Abdominal palpation and vaginal examination may reveal a mass arising from the pelvis. Ultrasound examination is usually performed to confirm the diagnosis, and this has high sensitivity and specificity as a test. If the relationship between the fibroid and the uterine cavity is unclear from an initial ultrasound assessment, HyCoSy or HSG may be useful to distinguish submucosal from intramural lesions. Hysteroscopic evaluation of the degree of myometrial penetration by the fibroid is essential if surgical excision is contemplated (Di Spiezio Sardo et al 2008). Discrimination between adenomyosis and fibroids may be facilitated with the use of ultrasound where the absence of a tumour capsule and lacunae within the lesion may be suggestive of the former. Magnetic resonance imaging can also be of help.

Potential endometrial abnormalities

Undiagnosed uterine pathology as a cause of infertility, recurrent implantation failure (RIF) or recurrent miscarriage is an attractive concept. However, the evidence that disturbed endometrial receptivity is important in infertility is mixed. Endometrial assessment by timed sampling and histological dating is the most described method of assessing the normality of endometrial development. It is dependent on accurate timing of sampling endometrium relevant to the LH surge (Li et al 2002), and has been largely abandoned in routine practice, as has the concept of luteal-phase deficiency as a major cause of infertility. Ultrasound-measured endometrial thickness is a poor predictor of implantation potential in in-vitro fertilization (IVF) (Margalioth et al 2006), particularly where high-quality embryos are available. Disturbances in cytokine expression and action have been postulated as a cause of RIF, but analysis of these factors remains a research tool rather than a clinical tool. The role of immunological causes and thrombophilia in infertility is also uncertain. Some early studies suggested an association between antiphospholipid syndrome and RIF, but this has not been confirmed in larger prospective studies. The role of natural killer cells in RIF is disputed (Rai et al 2005). For the moment, there is no convincing evidence for an association. An association between hereditary thrombophilia and RIF has also been described in some, but not all, studies, and screening for these disorders is still controversial (see Chapter 23, Sporadic and recurrent miscarriage, for more information).

Unexplained Infertility

Despite the use of investigation pathways as outlined above, it is debatable whether or not the basic tests of semen quality, ovulation and tubal patency are in any way accurate in predicting live birth (Taylor and Collins 1992). From the above discussion, it will also be clear that there is an ongoing, and relevant, debate concerning the existence of subtle disturbances in reproductive function in the female and their impact on fertility. While endometrial function is undoubtedly important in the genesis of conception, a number of other elements in the path to establishment of pregnancy have been considered as causes of infertility. Few are amenable to simple investigation. Possibilities are listed in Table 20.5.

| Endocrine factors |

Postcoital testing

An area of considerable interest over many years has been the assessment of sperm–cervical mucus interaction through the postcoital test (PCT). As the time of ovulation nears, cervical mucus secretion, under the influence of oestradiol, changes in quantity. After intercourse, sperm should swim freely within the mucus and transportation of sperm to the upper genital tract can take place. Cervical mucus–sperm hostility as a cause of infertility continues to be debated due to the methodological issues of concern in its use. The test is intrusive in so far as the couple are asked to have intercourse at a prescribed time, and then the female attends the clinic for a sample of mucus to be obtained from the cervix. The investigator examines the specimen to determine if there are motile sperm visible under light microscopy. In theory, the test could give an indication that intercourse has taken place, that timing is correct, that the mucus is receptive, and that sperm numbers and motility are adequate. In critically evaluating the usefulness of the PCT in clinical practice, many would argue that it lacks predictive power in its ability to identify those who will conceive naturally from those who will not (Oei et al 1995). Furthermore, there is no standardization of the methodology of the test; for example, timing of intercourse in relation to ovulation, timing of examination of sampled mucus relative to intercourse, and ‘normal’ sperm numbers and motility levels within examined mucus (Evers 2002). One study (Glazener et al 2000) found the PCT to be useful in predicting spontaneous conception in couples with otherwise unexplained infertility of a short duration (<3 years). However, a study which examined whether or not intrauterine insemination improved the chance of conception, where a PCT was negative, only showed a marginal effect (Mol 2001).

Diagnostic category

Unexplained infertility presents a frustrating diagnosis for both clinician and patient. The range and accuracy of the tests which are used to investigate the infertile will influence the chance of a ‘diagnostic label’ being attached to the problem (Gleicher and Barad 2006). Whether such a label leads to help in forming a prognosis or formulating a treatment plan is debatable (Siristatidis and Bhattacharya 2007). In some instances, the finding of ‘abnormality’ occurs with similar frequency in both those who ultimately conceive naturally and those who remain infertile (Guzick et al 1994). In recent times, the age profile of patients attending fertility clinics has changed, with many women delaying childbearing for a variety of reasons. For many, age alone is a major factor in determining prognosis, and age may also influence the probability of a diagnosis of unexplained infertility being made. It has been estimated that the chance of reaching a diagnosis of unexplained infertility is doubled if the female is over 35 years of age compared with females under 30 years of age (Maheshwari et al 2008). As discussed below, diminished ovarian reserve may, in theory, be a missed cause of infertility in otherwise unexplained infertility. For most clinics, female age, together with parity and the duration of infertility, are the three factors with the greatest bearing on prognosis.

Insights from Assisted Conception

The assisted conception population will usually include those who have prolonged infertility and, as such, is arguably not truly representative of the general infertility population. However, outcomes in those who access IVF treatment, although under very different conditions, may give some insight into what may be occurring in natural attempts to conceive, and afford help to couples in coming to terms with their infertility. Occasionally, poor fertilization outcomes may unmask functional problems regarding sperm or egg quality. Failed fertilization may be due to hardening of the zona pellucida, associated with ageing of the oocyte. Embryo quality, as judged by morphology and cleavage patterns, may be consistently suboptimal. The association with such findings and aneuploidy in embryos is well established. Women who fail to respond well to ovarian stimulation may have a qualitative or quantitative disturbance in follicular physiology. Tests of ovarian reserve to predict outcome have been widely used in those who are embarking on IVF treatment. Early-follicular-phase FSH, anti-Müllerian hormone, inhibin-B and ovarian-ultrasound-observed antral follicle count are the most popular measures. Dynamic tests of ovarian reserve have also been described using clomiphene or exogenous gonadotrophin stimulation. However, the predictive power of all these tests, relevant to a number of endpoints including eggs retrieved and clinical pregnancy, is poor, except at the extremes of ranges. For the moment, they should be regarded as unsuitable for routine evaluation of the infertile female (Maheshwari et al 2008).

Conclusions

KEY POINTS

Akande VA, Hunt LP, Cahill D, Jenkins JM. Difference in time to natural conception between women with unexplained infertility and infertile women with minor endometriosis. Human Reproduction. 2004;19:96-103.

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised American Society for Reprductive Medicine classification of endometriosis 1996. Fertility and Sterility. 1996;67:817-821.

Bhattacharya S, Porter M, Amalraj E, et al. The epidemiology of infertility in the North East of Scotland. Human Reproduction. 2009;24:3096-3107.

Borgfeldt C, Andolf E. Transvaginal ultrasonographic findings in the uterus and the endometrium: low prevalence of leiomyoma in a random sample of women age 25–40 years. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 2000;79:202-207.

Coppus SFPJ, Opmeer BC, Logan S, van der Veen F, Bhattacharya S, Mol BWJ. The predictive value of medical history taking and Chlamydia IgG ELISA antibody testing (CAT) in the selection of subfertile women for diagnostic laparoscopy: a clinical prediction model approach. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:1353-1358.

Crosignani PG, Olive D, Bergqvist A, Luciano A. Advances in the management of endometriosis: an update for clinicians. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12:179-189.

de Bruyne F, Hucke J, Willers R. The prognostic value of salpingoscopy. Human Reproduction. 1997;12:266-271.

Di Spiezio Sardo A, Mazzon I, Bramante S, et al. Hysteroscopic myomectomy: a comprehensive review of surgical techniques. Human Reproduction Update. 2008;14:101-119.

Evers JLH. Female subfertility. The Lancet. 2002;360:151-159.

Glazener CMA, Ford WCL, Hull MGR. The prognostic power of the post-coital test for natural conception depends on the duration of infertility. Human Reproduction. 2000;15:1953-1957.

Gleicher N, Barad D. Unexplained infertility: does it really exist? Human Reproduction. 2006;21:1951-1955.

Gnoth C, Frank-Hermann P, Freundl G, Godehardt D, Godehardt E. Time to pregnancy: results of the German prospective study and impact on the management of infertility. Human Reproduction. 2003;18:1959-1966.

Guzick DS, Grefenstette I, Baffone K, et al. Infertility evaluation in fertile women: a model for assessing the efficacy of infertility testing. Human Reproduction. 1994;9:2306-2310.

Hamilton MPR. The initial assessment of the infertile couple. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;2:2-7.

Hamilton JA, Larson AJ, Lower AM, Hasnain S, Grudzinskas JG. Evaluation of the performance of hysterosalpingo contrast sonography in 500 consecutive, unselected, infertile women. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:1519-1526.

Hull MG, Savage PE, Bromham DR, Ismail AA, Morris AF. The value of a single serum progesterone measurement in the mid-luteal phase as a criterion of a potentially fertile cycle (‘ovulation’) derived from treated and untreated conception cycles. Fertility and Sterility. 1982;37:355-360.

Hull MGR, Glazener CMA, Kelly NJ, et al. Population study of causes, treatment and outcome of infertility. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1985;291:1693-1697.

Johnson NP, Farquhar CM, Hadden WE, Suckling J, Yu Y, Sadler L. The FLUSH trial — Flushing with Lipiodol for unexplained (and endometriosis-related) subfertility by hysterosaplingograpgy: a randomized trial. Human Reproduction. 2004;19:2043-2051.

Khalaf Y, Ross C, El-Toukhy T, Hart R, Seed P, Braude P. The effect of small intramural uterine fibroids on the cumulative outcome of assisted conception. Human Reproduction. 2006;21:2640-2644.

Klatsky PC, Lane DE, Ryan IP, Fujimoto VY. The effect of fibroids without cavity involvement on ART outcomes independent of ovarian age. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:521-526.

Li TC, Tuckerman EM, Laird SM. Endometrial factors in recurrent miscarriage. Human Reproduction Update. 2002;8:43-52.

Lindborg L, Thorburn J, Bergh C, Strandell A. Influence of HyCoSy on spontaneous pregnancy: a randomised controlled trial. Human Reproduction. 2009;24:1075-1079.

Macmillan S, Templeton A. Screening for Chlamydia trachomatis in subfertile women. Human Reproduction. 1999;12:3009-3012.

Maheshwari A, Fowler P, Bhattacharya S. Assessment of ovarian reserve — should we perform tests of ovarian reserve routinely? Human Reproduction. 2006;21:2729-2735.

Maheshwari A, Hamilton M, Bhattacharya S. Effect of female age on the diagnostic categories of infertility. Human Reproduction. 2008;23:538-542.

Marcoux S, Maheux R, Berube S. Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:217-222.

Margalioth EJ, Ben-Chetrit A, Gal M, Eldar-Geva T. Investigation and treatment of repeated implantation failure after IVF-ET. Human Reproduction. 2006;21:3036-3043.

Mol BW. Diagnostic potential of the post-coital test. In: Heineman MJ, editor. Evidence Based Reproductive Medicine in Clinical Practice. Birmingham: American Society for Reproductive Medicine; 2001:73-82.

Mol BWJ, Swart P, Bossuyt PMM, van Beurden M, van der Veen F. Reproducibility of the interpretation of hysterosalpingography in the diagnosis of tubal pathology. Human Reproduction. 1996;11:1204-1208.

National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health for the National Institute of Clinical Excellence. Fertility: Assessment and Treatment for People with Fertility Problems. London: RCOG Press; 2004.

Oei SG, Helmerhorst FM, Keirse MJNC. When is the post-coital test normal? A critical appraisal. Human Reproduction. 1995;10:1711-1714.

Oliva A, Spira A, Multigner L. Contribution of environmental factors to the risk of male infertility. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:1768-1776.

Rai R, Sacks G, Trew G. Natural killer cells and reproductive failure — theory, practice and prejudice. Human Reproduction. 2005;20:1123-1126.

Rimbach S, Bastert G, Wallwiener D. Technical results of falloposcopy for fertility diagnosis in a large multicentre study. Human Reproduction. 2001;16:925-930.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Human Reproduction. 2004;1:41-47.

Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS Consensus Workshop Group. Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertility and Sterility. 2004;81:19-25.

Siristatidis C, Bhattacharya S. Unexplained infertility: does it really exist? Does it matter? Human Reproduction. 2007;22:2084-2087.

Snick HKA, Snick TS, Evers JLH, Collins JA. The spontaneous pregnancy prognosis is untreated subfertile couples: the Walcheren primary care study. Human Reproduction. 1997;12:1582-1588.

Somigliana E, Vercellini P, Daguati R, Pasin R, de Giorgi O, Crosignani PG. Fibroids and female reproduction: a critical analysis of the evidence. Human Reproduction Update. 2007;13:465-476.

Swart P, Mol BWJ, van der Veen F, van Beurden M, Redekop WK, Bossuyt PMM. The accuracy of hysterosalpingography in the diagnosis of tubal pathology, a meta-analysis. Fertility and Sterility. 1995;64:486-491.

Taylor PJ, Collins JA. Unexplained Infertility. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1992.

Templeton A, Fraser C, Thompson B. The epidemiology of infertility in Aberdeen. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1990;301:148-152.

Wathen NC, Perry L, Lilford RJ, Chard T. Interpretation of single progesterone measurement in diagnosis of anovulation and defective luteal phase: observations on analysis of the normal range. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 1984;288:7-9.