CHAPTER 20 Dislocations of the Child’s Elbow

INTRODUCTION

Dislocation of the elbow in children is the most common childhood dislocation, constituting about 6% to 8% of elbow injuries.72,118 In general, however, because the attachments of ligaments and muscles are stronger than the adjacent growth plate, forces exerted about most joints tend to result in epiphyseal injury rather than simple dislocation of the adjacent joint. The elbow is unique in children because type I and II fractures through the distal humeral epiphysis are uncommon; hence, the finding for dislocation.

The purpose of this chapter is to discuss the practical aspects of the cause, recognition, and the management of dislocations about the elbow joint in children. Because the elbow is the most common joint injured in childhood, the chapter on imaging (see Chapter 12) and chapters dealing with images of other conditions (see Chapters 14 to 18 and Chapter 21) should be carefully studied.

ANATOMIC FACTORS PREDISPOSING TO ELBOW DISLOCATION IN CHILDREN

Although the anatomy of the elbow joint was thoroughly discussed in Chapter 2, it is important to emphasize some of the anatomic differences that are unique to the pediatric elbow joint.

GROWTH PLATES, APOPHYSIS, AND SECONDARY CENTERS OF OSSIFICATION

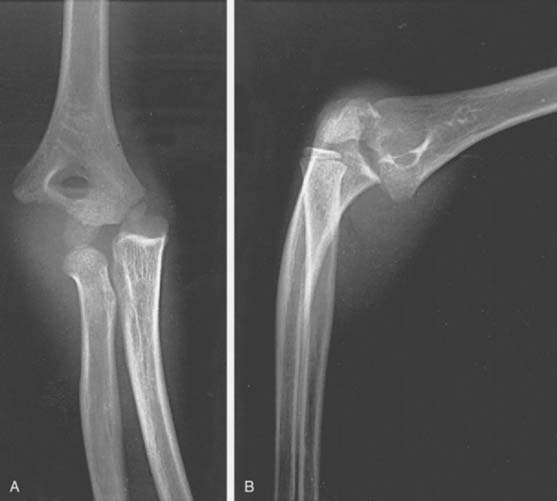

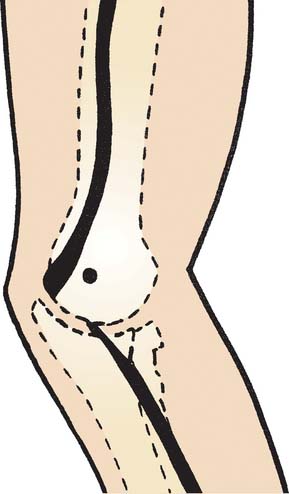

In general, the younger the child at the time of injury, the more difficult it is to assess the elbow, owing to the larger percentage of cartilage that is present about the elbow joint. Fortunately, new imaging modalities allow more accurate assessment.7,8 Yet, in the newborn or infant, it may be very difficult to diagnose an elbow injury or to determine whether it is a transcondylar fracture or a dislocation of the elbow (the former being much more common at this age). The ossific nuclei about the elbow joint are helpful in radiologic interpretation of elbow dislocation (see Chapter 12). The capitellum, whose center of ossification should be present by 6 months of age, facilitates the interpretation of radial head alignment, because a line drawn through the radial head should always intersect the capitellum no matter what view is taken (Fig. 20-1). This interpretation is improved even further with the appearance of the radial head secondary center of ossification, at around 5 years of age. The secondary center of ossification of the olecranon, which appears at about 9 years of age, allows a more accurate assessment of the position of the proximal ulna in relation to the distal humerus, an important consideration in the management of dislocations of the elbow in young children.

The lateral epicondylar apophysis is injured less frequently. In posteromedial dislocations, it may suffer avulsion, owing to a severe varus strain on the elbow and may need to be repaired or fixed surgically.5

ELBOW FLEXIBILITY

In children younger than 10 years of age, elbow stability is provided almost entirely by cartilage. Because of this, there is considerable flexibility in the elbow joint in children. It is not unusual for a child to be able to hyperextend the elbow joint by 10 or 15 degrees and to have a much greater degree of laxity than is seen in an adult or even an adolescent. It is this combination of hyperflexibility and a lack of osseous stability in a joint subjected to considerable trauma that predisposes the elbow joint to dislocation. The major stabilizing ligaments on the medial and lateral sides are attached to the distal humerus through apophyses—structurally weak areas that are prone to avulsion with subsequent loss of joint integrity. In the many syndromes and conditions such as Ehlers-Danlos and cutis laxa syndromes,111,119 ligamentous laxity is enhanced and stability is accentuated.

RADIAL HEAD AND NECK

The radial head and neck in children are cartilaginous but have the same relative diameters as the radial head and neck in adults. Dislocation of the radial head, either as an isolated event or in association with a Monteggia fracture, or with dislocation of the elbow joint itself, is facilitated by the resiliency of the cartilaginous component. Children’s bones have plasticity and can be bent like the proverbial greenstick without fracturing. In the type A Monteggia lesion, for instance, it is conceivable that the ulna bends to the point of fracture, whereas the radius only bends to the point at which the radial head slips under the annular ligament and dislocates anteriorly (Fig. 20-2).

TYPES OF DISLOCATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION

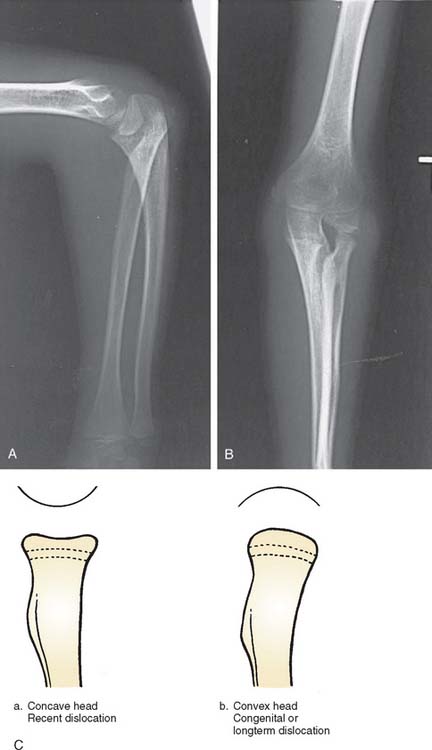

Congenital dislocation of the radial head is a controversial lesion, because some maintain this lesion does not exist at all and all such appearances are simply traumatic or developmental dislocations. This subject is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13. Here, I reserve the diagnosis of congenital dislocation for that entity in which congenital malformation of the extremity is obvious (Fig. 20-3). When isolated dislocation of the radial head is not accompanied by other congenital lesions, the congenital basis for the lesion cannot be substantiated. The long-standing nature of the dislocation can be inferred from the marked convexity of the radial head associated with elongation of the radial neck (Fig. 20-4).27,28 Congenital dislocation of the radial head may be associated with radioulnar synostosis, the synostosis almost always occurring between the proximal radius and the ulna.32–36

Hypoplasia of the capitellum associated with dislocation of the radial head strongly suggests that the dislocation is congenital. The radiologic appearance of congenital dislocations of the radial head has been emphasized by Miura.37 In congenital dislocations, the posterior border of the ulna is usually concave rather than slightly convex, with the radial head being dome-shaped with no central depression (see Fig. 20-3). Posterior congenital dislocation, which constitutes about 40% of congenital dislocations of the radial head, is associated with an accentuation of the normal convexity of the posterior border of the ulna. In fact, because we have not been able to diagnose this pathology, at best, we consider this a developmental problem.28

DEVELOPMENTAL DISLOCATION

Many instances of developmental or secondary dislocation of the radial head are misinterpreted as being congenital in origin.28 Developmental dislocation is defined as any dislocation of the radial head that results from maldevelopment of the forearm. There are many inherited and acquired disease processes affecting the growth plate of the forearm bones that result in asymmetric growth between the radius and the ulna and subsequent dislocation of the radial head. These include the nail patella syndrome, Silver syndrome, arthrogryposis, Cornelia de Lange syndrome, and cleidocranial dysostosis. Asymmetric growth also occurs in multiple exostoses or diaphyseal aclasis. The ulna is most frequently affected at the distal ulnar growth plate; the radius then overgrows relative to the ulna (Fig. 20-5). Paralysis of the muscles innervated by the C5-6 nerve root, as in a nerve root palsy, also predisposes to a gradual dislocation of the radial head that occurs over a number of years of growth or occasionally in infancy.17 Cerebral palsy also may produce isolated dislocation of the radial head through marked spasticity of the muscles attached to the radius (Fig. 20-6).21 Trauma to the radius or the ulna, resulting in asymmetric growth, may also produce dislocation of the radial head. Fracture of the neck of the radius that has not been corrected adequately may result in the proximal radial epiphysis growing laterally instead of toward the capitellum (Fig. 20-7).20–26

FIGURE 20-5 A to D, Dislocation of the radial head posterolaterally in a patient with multiple exostoses.

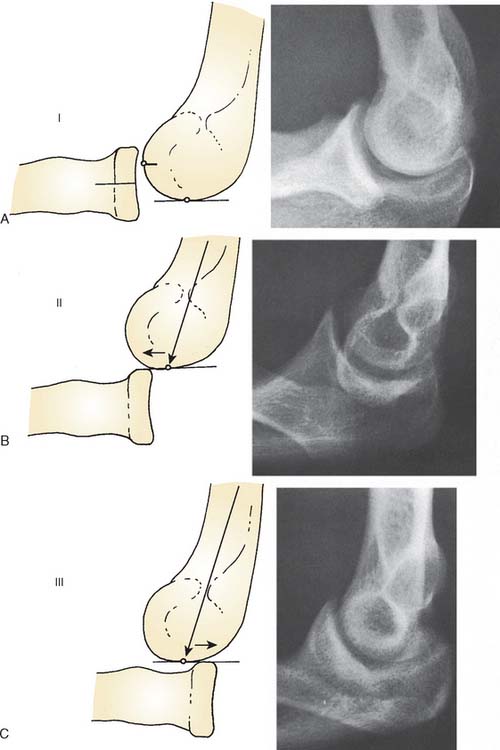

A detailed developmental posterior study at the Mayo Clinic describes several grades, or types, of radial head dislocation with characteristic radiographic appearance (Fig. 20-8). Types II and III are complete dislocations and are more obvious cosmetically but have relatively little functional loss except forearm rotation.28 Type I dislocations commonly are associated with late degenerative arthrosis and consist more of a subluxation than a frank dislocation. However, consistent with the definition of forearm maldevelopment, all types have a previous proximal ulnar bow.

There are few indications for operative treatment of developmental dislocation of the radial head. For example, a malunion of the radius and the ulna that is obviously directing the head of the radius laterally, posteriorly, or anteriorly should be corrected with an osteotomy to redirect the proximal radius or the deformed ulna19; otherwise, excision of the radial head can be effective to improve motion, lessen pain, or to improve cosmesis.

In patients with cerebral palsy, if the bicipital tendon appears to be subluxating the radial head anteriorly, lengthening the biceps may prevent future dislocation. Once the dislocation is well established, attempts to relocate the radial head probably should not be made, and the dislocation should be accepted. Future resection of the radial head at skeletal maturity can be performed if the head is cosmetically or functionally a problem. The gradual nature of the dislocation and adjacent changes in the surrounding tissues and bone make this type of relocation of the radial head much more difficult than the acute traumatic injury.26

RADIOGRAPHIC APPEARANCE

The radiographic appearance of a long-standing dislocated radial head is characterized by a rounded contour or convexity in contrast to the normal concave appearance (see Fig. 20-4). The posterior border of the ulna also may be concave rather than slightly convex in anterior dislocations of the radial head. Posterior dislocations result in a longer neck with a typical dome-shaped head. Even an isolated traumatic dislocation of the radial head, when it occurs in a very young child, may take on the appearance of a congenital or developmental dislocation with the passage of time. A relative increase in ulnar length in relation to the radius and the wrist is often noted. With posterior dislocation, proximal ulnar bowing also is prominent, and proximal radial migration of the radius may be present.28 The capitellum may be hypoplastic or, occasionally, even absent.38

Other factors characteristic of congenital or developmental radial head dislocations have been reported to be bilaterality of involvement,28 association with other congenital anomalies, familial occurrence, absence of traumatic history, and the presence of the entity in a patient younger than 6 months of age17–24 (see Chapter 13).

NATURAL HISTORY

Developmental dislocation of the radial head seldom causes severe pain with anterior dislocation. Patients may complain of clicking or impingement at the ulnohumeral joint with flexion of the elbow. In our experience, this is not seen until adolescence or adulthood. Posterior dislocation of the radial head typically creates a cosmetic protuberance that also may be a source of pain with excessive elbow motion.28 Aching in the region of the dislocation is common in the older child. A prominent ulna at the wrist and the resultant radioulnar subluxation at the distal end may result in some limitation of motion at the wrist, but discomfort is uncommon. There does not appear to be any progressive loss of motion with further growth, and the joint limitation, if present, remains static.20,28

TRAUMATIC DISLOCATION

The history is of limited value in these cases because these children are often young, prone to frequent elbow injuries, and unable to make a reliable contribution to the history. The radiograph, however, is usually diagnostic because it shows the rounded concave appearance of the radial head in the congenital or developmental dislocation (see Fig. 20-4).1–16

CLINICAL FEATURES OF ISOLATED ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

Radiographically, a line drawn through the shaft of the radius and the radial head will not intersect the capitellum when the radial head is dislocated (see Fig. 20-1). Children who have been subjected to child abuse may present with this particular injury, and again, the history will be difficult to elicit.

TREATMENT OF ACUTE ANTERIOR DISLOCATION

OPEN REDUCTION

Triceps Fascial Reconstruction

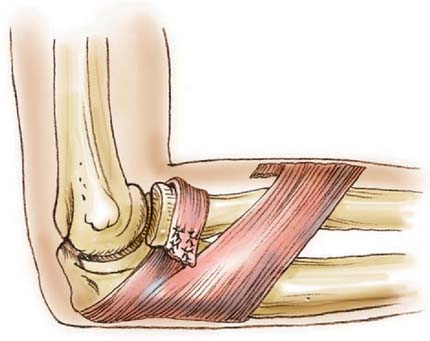

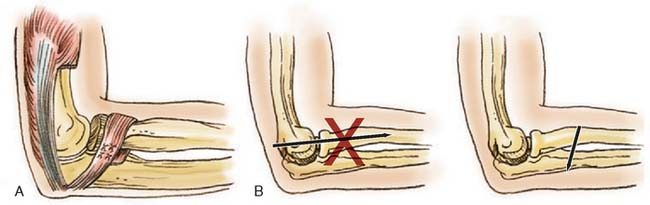

The technique of open reduction of an anterior dislocation of the radial head in children described by Lloyd-Roberts and Bucknill20 is one I have used with success. This consists of using the lateral portion of the tendon of the triceps for reconstruction of the annular ligament (Fig. 20-9A).

A posterolateral incision is preferred rather than a posterior incision, which may disorient the surgeon to the position of the radial head. The triceps tendon is identified, and a long (10-cm) strip is removed from the lateral margin, ensuring attachment at the distal ulnar insertion. The tendon is increased in length by continuing the dissection through the periosteum to a point opposite the neck of the radius, where it is then passed around the neck and sutured to itself and the ulnar periosteum with enough tension to hold the radial head in place. A Kirschner wire is then passed through the ulna into the radius to ensure solid fixation until the tendon has healed (see Fig. 20-9B).18

Specific care must be exercised when exposing the neck of the radius in a child. Unlike the adult, the radial nerve may be only a fingerbreadth below the head of the radius rather than the classic two fingerbreadths that is often referenced.

Fascial Reconstruction of the Annular Ligament

If inadequate, the annular ligament may be reconstructed. A strip of fascia is dissected from the forearm muscles but is left attached to the proximal ulna. The length of this fascial strip should be about 5 inches by 1/2 inch. It is passed around the neck of the radius, proximal to the tuberosity and distal to the radial notch of the ulna, and is brought around and fastened to itself with nonabsorbable sutures (see Fig. 20-9). Care should be taken to ensure that the length of this fascial strip is adequate. Cross-radioulnar pin fixation for 4 weeks is reassuring.

COMPLICATIONS

Relocation of an acute dislocation of the radial head in a child is usually successful, and recurrence is uncommon. If not reduced, limited motion and cosmetic deformity ensue. The dislocated radial head may also result in a relative shortening of the radius compared with the ulna, with subsequent subluxation at the radioulnar joint at the wrist. As a general rule, the radial head should not be excised in a child because this may further aggravate shortening of the radius by eliminating the proximal radial growth plate, which contributes about 30% of the final radial length. If there is pain or a grotesque appearance when the child is near skeletal maturity, the radial head is easily removed. In neglected patients, excision of the radial head may allow improved flexion and rotation and may alleviate complaints of pain and discomfort.28

PEDIATRIC MONTEGGIA FRACTURE DISLOCATION

The Monteggia injury is uncommon in children but by no means rare. In the 5-year period from 1978 to 1982 at the Winnipeg Children’s Hospital, 33 children were treated for a variety of Monteggia lesions. The true incidence of this fracture-dislocation is unknown, but it is more common than is generally appreciated. Olney and Menelaus53 reported 102 children with acute Monteggia lesions over a 25-year period.

ETIOLOGY

The most common cause of dislocation of the radial head associated with an ulnar fracture in childhood is a hyperextension injury,44,62 followed by a hyperpronation injury.45 In hyperpronation, Bado39 pointed out that the bicipital tuberosity is posterior, thus predisposing the proximal radius to the greatest force during violent contraction of the bicipital tendon. In young children, the force generated by the biceps is less than that in the adult, and this mechanism probably is significant only in older children.

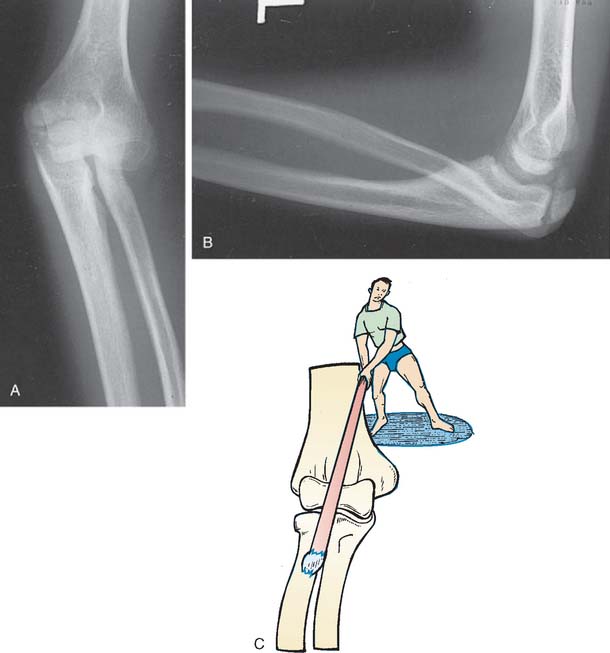

Because of the plasticity of the forearm bones, the radial head and neck may slip under the annular ligament and dislocate as the shaft of the radius bends. Indeed, many of the isolated traumatic dislocations of the radial head are undoubtedly variations of the Monteggia46–48 (Monteggia equivalent), in which the ulna has simply bent but not fractured. The radial shaft is bent to the extent that the head and neck are slipped from within the annular ligament, resulting in an apparent isolated dislocation of the radial head.30,43

CLASSIFICATIONS

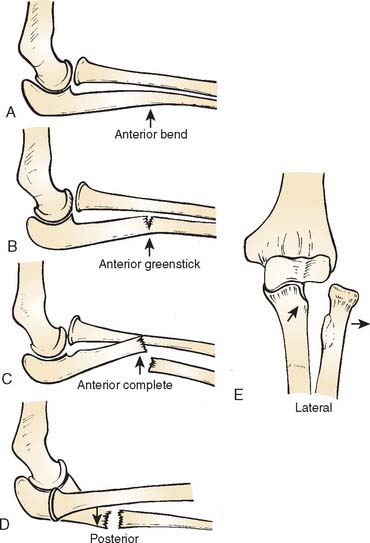

Classifications of the Monteggia lesion are based largely on the injury in adults39 (see Chapter 27). Because of differences in the configuration of the injury in childhood, the following pediatric classification is suggested to include dislocation of the radial head associated with the plasticity of the forearm bones in childhood (Fig. 20-10).

CLASSIFICATION OF PEDIATRIC MONTEGGIA LESIONS

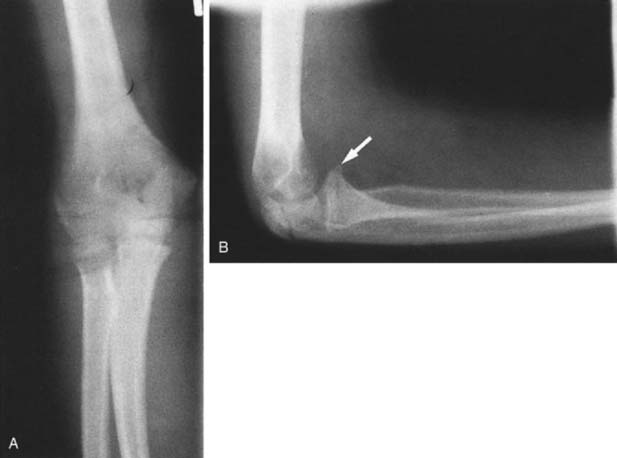

Type A: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with anterior bowing of the ulna (Fig. 20-11).

FIGURE 20-11 A and B, Ulnar bend with lateral dislocation of the radial head, a type A Monteggia fracture dislocation.

Type B: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with greenstick fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-12).

Type C: Anterior dislocation of the radial head with transverse fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-13).

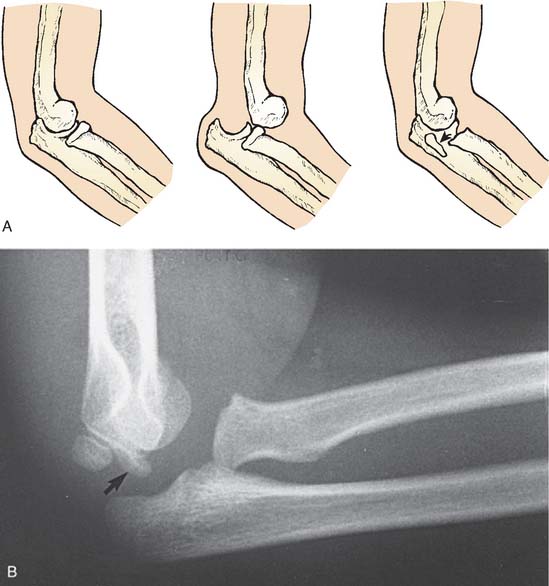

Type D: Posterior dislocation of the radial head with bending or fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-14).

FIGURE 20-14 A and B, Posterior lateral dislocation of the radial head with bending or fracture of the ulna.

Type E: Lateral dislocation of the radial head with fracture of the ulna (Fig. 20-15).

Types B and C are the most commonly encountered Monteggia lesions in children.51

CLINICAL DIAGNOSIS

Like Monteggia himself, who described this injury initially in a young woman in 1814, long before the advent of radiography, most physicians today should be able to identify the clinical configuration in those seen early, before swelling has occurred (see Fig. 20-15). The dislocation of the radial head is often evident on inspection of the lateral aspect of the elbow joint. Angulation of the ulna, whether fractured or not, necessitates careful appraisal of the position of the radial head. Dislocation of the radial head is frequently missed by those who treat pediatric elbow injuries only occasionally.52–58 A line drawn through the shaft and the neck of the radius should intersect the capitellum in all views taken (see Fig. 20-1). If it does not, dislocation of the radial head is highly suspect.

In contrast to the lesion in adults, overlap of the ulnar fragments is not a prerequisite for dislocation of the radial head in a child. Disruption of the forearm parallelogram may occur as a result of ulnar bend when the radial head slips out of the annular ligament. It is wise to obtain anteroposterior and lateral views of the elbow joint in all fractures of the ulna. The apex of the ulnar bend or angulation is always in the direction of the radial head dislocation.51–65

TREATMENT

In contrast to the adult, the Monteggia injury in children usually can be treated by closed methods.31 Pressure directed over the dislocated radius usually will result in a stable ulnar reduction, provided that immobilization is imposed with the elbow flexed more than 90 degrees in types A, B, C, and E lesions. Supination assists in minimizing biceps pull. In the uncommon type D Monteggia lesion with posterior dislocation of the radial head, stability is obtained with extension, not flexion, of the elbow.

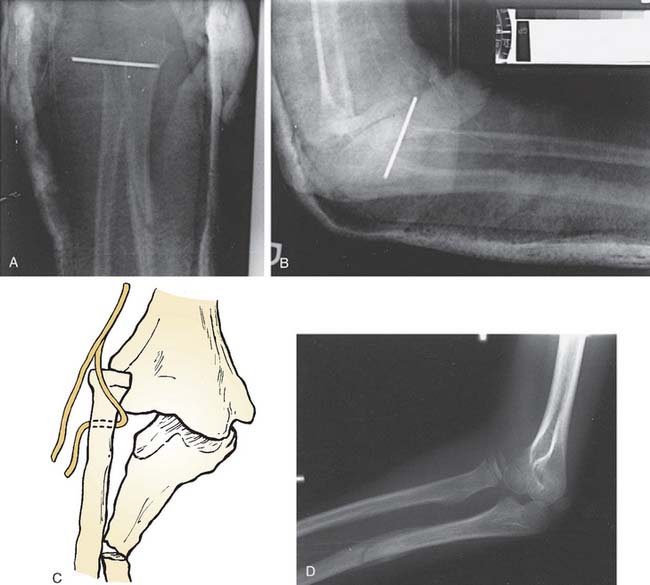

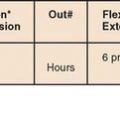

If it is impossible to obtain a stable reduction of the radial head, I approach the radial head through a Kocher incision and reapproximate the annular ligament around the neck. If stability is still precarious or if the annular ligament has had to be reconstituted, I recommend internal fixation of the radius to the ulna with a Kirschner wire (Fig. 20-16A). As noted earlier, I would caution against maintenance of the reduction by a wire inserted through the capitellum and into the radial head. Fatigue fracture is always a possibility (see Fig. 20-8B).

If the ulna is unstable in the older child, an open reduction with plate fixation may be necessary, but in my experience, this is seldom required in those under 10 years of age.58

NERVE INJURY ASSOCIATED WITH MONTEGGIA LESIONS

Anterior dislocation of the radial head may result in a traction injury to the posterior interosseous nerve as it passes dorsolaterally around the proximal radius to enter the substance of the supinator muscle mass between the superficial and deep layers (see Fig. 20-16B).46,60 Compression of the posterior interosseous nerve also may be aggravated by the fibrous arcade of Frohse, a firm fibrous band at the proximal edge of the supinator muscle.59

In children, nerve injury is less common than in adults, and recovery is the rule in closed injuries. In a large series of 102 Monteggia fractures, Olney and Menelaus53 found a 10% incidence of nerve injuries, 6% involving the posterior interosseous nerve and 3% involving the radial nerve. All their nerve injuries healed completely within 6 months.

THE MISSED MONTEGGIA LESION

The dislocated radial head that is noticed only after the ulna has healed is a common error made by less experienced clinicians and in some instances the initial injury has almost been forgotten (see Fig. 20-16D). Some confusion may occasionally arise in connection with the congenital dislocated radial head, but in general, the contour of the radial head should be diagnostic—the congenital lesion having a rounded convex head whereas the recently dislocated radius usually has a concave appearance. It can be appreciated that the younger the child, the more difficult it will be to make this interpretation, owing to the large cartilaginous component of the proximal radius.40–44,46,50

DISLOCATION-SUBLUXATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD FOLLOWING MALUNION OF A RADIAL NECK FRACTURE

Fractures of the radial neck in children that have occurred after the age of 6 or 7 years may, if unreduced, result in a subluxation (see Fig. 20-7). When neck angulation is more than 45 to 50 degrees, the growth plate becomes redirected laterally or posterolaterally. If there is not enough remodeling to allow the growth plate to reattain its normal transverse anatomy, increased prominence of the radial head ensues. As the child grows, pain may be experienced, as well as irritation, cosmetic deformity, and, to a lesser extent, limitation of supination and pronation. This can be avoided by ensuring that the angulation of the radial neck is reduced to less than 45 degrees by closed or open reduction.63

When associated with malunion of the ulna radial head, instability may necessitate osteotomy of the ulna and open reduction of the radial head. It is of course always prudent to attempt a closed reduction of the radial head if the injury has occurred recently (i.e., within 2 months) because the ulna may still be straightened. Usually, however, in the missed Monteggia lesion, an open reduction of the radial head will be necessary, and in this instance, it will almost certainly be necessary to reconstitute the annular ligament—with the ligament itself, if possible, with fascia obtained from the triceps, or by using the Bell-Tawse procedure.42,44,49 Shortening of the radius may be necessary to permit reduction. Internal fixation with Kirschner wires through the radius to the ulna is advisable. Relocation of the radial head should be attempted in children younger than 6 years of age.18 In older children in whom the lesion has been present for more than 1 year, it may be advisable to accept the dislocation because this is compatible with excellent function in most instances. A modified technique for reconstruction of the annular ligament has been reported by Peterson and Seel,56 which appears effective in patients with long-standing radial head dislocations. If the radial head becomes cosmetically or functionally disabling, excision is performed as needed when skeletally mature. Removal of the radial head is avoided until skeletal maturity since 30% of radial growth occurs at the proximal radial epiphysis.

PULLED ELBOW SYNDROME

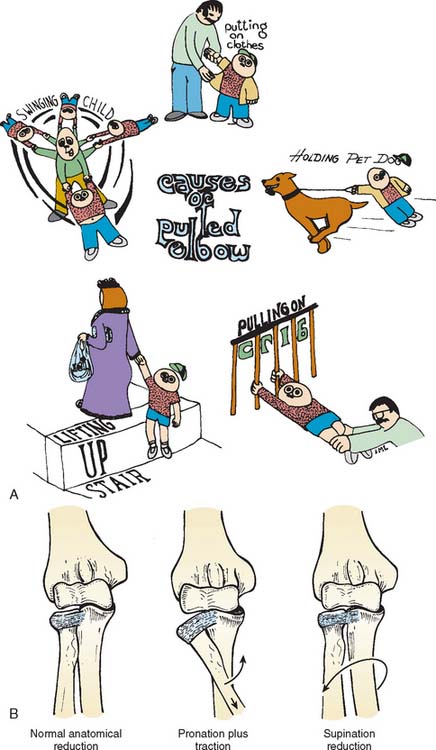

Nursemaid’s elbow, or pulled elbow syndrome, has been recognized since early in this century.124 Some children seem to be particularly prone to this injury, and for them, even minor pulls on the arm result in the typical pain and failure of elbow motion that is always of concern to parents (Fig. 20-17A).123,124

FIGURE 20-17 A, Some causes of pulled elbow syndrome in small children. B, Pathophysiology of the pulled elbow syndrome.

ETIOLOGY

Subsequent to a longitudinal pull on the forearm, the radial head is pulled down into the annular ligament (see Fig. 20-17B). This results in inability to rotate the radial head without considerable discomfort. Usually, the annular ligament is not torn; however, as the child becomes older, the annular ligament is undoubtedly partially torn, which accounts for the persistence of symptoms for several days even after the reduction. At one time, it was thought that the radial head in a child was smaller in relation to the neck than in adults or older children, and thus, subluxation of the radial head into the annular ligament was more common.125 Studies by Salter and Zaltz129 and Mehta127 have shown that, even in infants, the relative proportion of radial head diameter to neck diameter is similar to that of adults.

The pulled elbow syndrome is most common between the ages of 6 months and 3 years, becoming less common as the radius grows in size and becomes more ossified.126 A reasonable explanation for pulled elbow is simply the generalized ligamentous laxity of the elbow that exists at this age and the resiliency imparted to the radial head by the almost entirely cartilaginous structure.122,123 A longitudinal pull with accompanying pronation of the forearm screws the radial head down into the annular ligament, and the larger head then becomes caught as if in a Chinese finger trap (see Fig. 20-17B).

CLINICAL APPEARANCE

A child with the pulled elbow syndrome complains primarily of pain and failure to move the elbow, and there may or may not be a typical history of a longitudinal pull. The infant may well go about his or her normal play activities and is comfortable as long as no one attempts to move the elbow. The child keeps the arm in pronation and expresses discomfort and anxiety if anyone attempts to move the elbow or to pronate or supinate the forearm. Radiographs are singularly nondiagnostic and are sometimes misinterpreted because it is impossible to position the limb properly.124–129 However, the technicians, in attempting to obtain good anteroposterior and lateral films of the elbow, may inadvertently reduce the subluxation by supinating the forearm, and the child returns from the Radiology Department content and moving his or her elbow normally.

TRAUMATIC DISLOCATION OF THE ELBOW

MECHANISM OF THE DISLOCATION

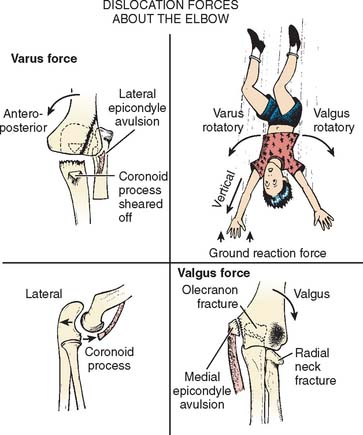

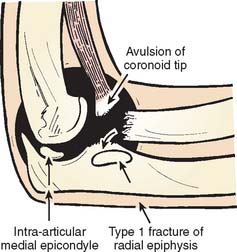

As discussed earlier, the elbow joint in a child is basically a ligamentous structure in which only a small portion of cartilaginous stability is imparted by the ulna. With a fall on the outstretched hand the downward force on the fixed forearm is considerable. An associated valgus or varus force created by the body falling over the fixed elbow occurs (Fig. 20-18). The forearm is typically in pronation during this time. The coronoid process may be fractured (Fig. 20-19). The valgus force of the body rotating over the fixed elbow accounts for the frequent avulsion of the medial epicondylar apophysis (Fig. 20-20).71,83 If the body falls over the elbow medially instead of laterally, a varus force is exerted, and the lateral epicondyle of the humerus or the lateral condyle may be avulsed84 (Fig. 20-21). Occasionally, as in a fall from a height, the forces may be such that the valgus force may disrupt the medial apophysis, and the posterolateral dislocation may also avulse the lateral epicondyle, resulting in elbow instability on both the ulnar and the radial sides of the joint. The radius and the ulna seldom separate owing to the strong interosseous membrane, although instances of divergent dislocations with tearing of the interosseous membrane have been reported.75,81,86,96 Less commonly, traction injuries may result in elbow dislocation.80

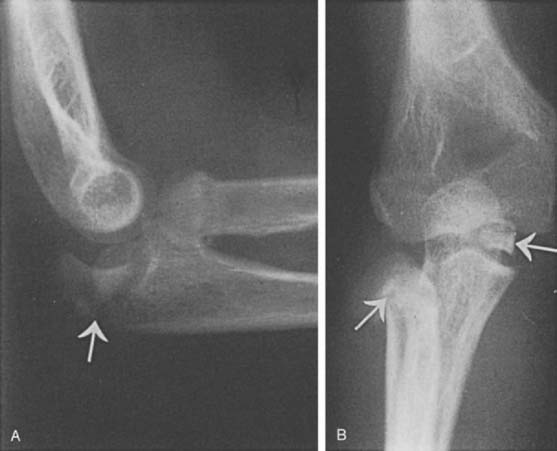

FIGURE 20-19 A and B, Fracture of coronoid process of olecranon associated with posterior dislocation of the elbow.

Occasionally, in falls from a height, the valgus force exerted on the elbow joint may result in a fracture of the neck of the radius and the olecranon process (Fig. 20-22). When the arm is in marked extension, the capitellum also may be fractured. Associated fractures of the distal radius and ulna occasionally occur (Fig. 20-23).

SPONTANEOUS REDUCTION OF THE DISLOCATED ELBOW

Spontaneous reduction of a dislocated elbow in children is common. Often the child will present to the emergency department with a history of a fall, the only physical findings being a swollen, boggy elbow and no obvious radiographic evidence of any injury. However, if one looks carefully at the radiograph, signs of previous dislocation may be present (Fig. 20-24). Of particular note is fracture of the coronoid process (Fig. 20-25), which indicates that the elbow has been transiently subluxed.

FIGURE 20-24 Fractures about the elbow in children indicative of spontaneous reduction of an elbow dislocation.

Sometimes, at reduction the humerus may cause a type I or II fracture through the epiphyseal plate of the proximal radius, resulting in posterior displacement of the radial epiphysis on reduction (Fig. 20-26).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

The child with dislocation of the elbow is severely incapacitated with pain and deformity. The differential diagnosis basically consists of distinguishing a dislocation from a supracondylar fracture, a lateral condylar fracture, and, in the younger child, a transcondylar fracture of the humerus (Fig. 20-27).92 The elbow will be painful and swollen, and depending on how soon the child is seen after the injury, the posterior deformity may be either obvious or masked by swelling if several hours have passed. The child is always extremely apprehensive and will not allow anyone under any circumstances to move the joint.

The neuromuscular examination of the extremity may be difficult but often can be performed simply by observation once the confidence and cooperation of the child have been obtained. Sensation then can be gently tested in the three major nerve distributions, including the anterior and posterior interosseous divisions. It is essential, of course, to assess the neurologic and vascular condition of the limb in the Emergency Department. The child should be encouraged to make the “O” sign with the index finger and thumb. If this cannot be done, injury to the anterior interosseous nerve has occurred, causing paralysis of the flexor pollicis longus. Images are diagnostic today. Dislocation of the elbow is very rare in children younger than the age of 2 years, and transcondylar fracture of the humerus should be suspected (see Fig. 20-25). This may be difficult to differentiate from a posterior dislocation, and confirmation may require special images.68–74,76,79,82

Radiographs should be carefully examined for associated fractures aside from the dislocation. A careful appraisal of the coronoid process, the radial neck, the olecranon, and the medial and lateral epicondyles should be carried out.67,77,78,84 If the child is over 5 years of age and the medial epicondyle is not present, a radiograph of the other elbow should be inspected to make sure that it is ossified. If the medial epicondyle cannot be found on the radiograph of the dislocated elbow, it must be assumed that it is obscured by its intra-articular position (see Fig. 20-20).66,71,89–95

An injury to the radial epiphysis may occur when the elbow is forcibly reduced. This may even occur at the time of the injury; for example, when a direct blow to the elbow, following the original dislocation that was sustained by a fall on the outstretched hand, causes reduction. The direct force on the radial head results in a type I fracture through the proximal radial epiphysis with posterior displacement (see Fig. 20-26).

TREATMENT OF POSTERIOR DISLOCATION

Occasionally, in a very cooperative older child, the elbow may be reduced in the emergency department. The instillation of local anesthetic into the joint itself often facilitates this maneuver. Turning the child prone with the arm dangling over the stretcher facilitates the application of some pressure over the olecranon, and this, combined with gravity or slight traction on the dangling limb, may allow the dislocation to be quickly and traumatically reduced.87 If there is an associated fracture of the medial epicondyle, the radial neck, or the olecranon, this maneuver should be avoided.

Once the child has been anesthetized, it is usually a simple matter to reduce an uncomplicated posterior elbow dislocation. Gentle traction on the forearm combined with some anterior pressure over the prominent olecranon is usually successful, usually with an audible and palpable clunk (Fig. 20-28).

FIGURE 20-28 The author’s preferred technique for reducing a posterior dislocation of the elbow joint in children.

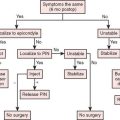

Occasionally, in older children, the coronoid process becomes locked behind the humerus. In this instance, the arm should be put in extension and a muscle relaxant administered; with traction and good firm thumb pressure over the olecranon, the elbow usually can be reduced. Hyperextension to free the coronoid is hazardous, especially if vascular insufficiency is already present, because it places more stress on the brachial artery, which may be tented over the distal end of the humerus. Once the elbow is reduced, the integrity of the medial and lateral collateral ligaments should be tested. Furthermore, a smooth arc of motion should be demonstrated to ensure no fragment, particularly the medial epicondyle, is caught within the joint. If the joint does not move freely or has a spongy feel to it, a mechanical problem with reduction exists. The reduction should always be checked radiographically, especially with any associated fracture.85,94,97

MEDIAL EPICONDYLAR ENTRAPMENT

If it is known that the medial epicondyle is trapped within the joint, then during the reduction, a valgus strain is placed on the elbow. With flexion of the wrist this may allow the attached flexor muscle mass to pull the trapped fragment out of the joint. Occasionally, this may yield an anatomic or nearly anatomic position. If the medial epicondyle is displaced more than 1 cm, it should be pinned back in place because it will add stability to the elbow subsequent to the dislocation and allow stable elbow motion to occur within 3 to 4 weeks. In children younger than the age of 5, when the medial epicondyle is not ossified, any springiness in the elbow joint subsequent to the reduction indicates an intra-articular position of the medial epicondyle. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the elbow might be helpful in confirming the presence of an intra-articular fragment.74 If the medial epicondyle cannot be removed from the joint with manipulation, it must be removed surgically. The elbow is approached through a medial incision. The flexor muscle mass initially appears to be anatomically intact as it disappears into the joint; however, with valgus force and gentle pull on the muscle mass, the attached fragment can be removed from the joint, and the capsule can be repaired. The fragment then should be reattached to the distal medial humerus. Care should be taken not to injure the ulnar nerve. If there is any concern about this, the nerve should be identified and retracted with tapes until the repair has been completed.66,89,95,109

OTHER TYPES OF ELBOW DISLOCATION

Anterior Dislocation

Anterior dislocation of the elbow in children is uncommon and usually is the result of severe direct trauma to the posterior aspect of the proximal forearm. This may be associated with a fracture of the olecranon. Reduction should be accomplished by direct pressure anteriorly over the dislocated radius and ulna, together with gentle traction on the forearm to allow the olecranon to slide beneath the humerus.72,88

Medial or Lateral Dislocation

Purely medial or lateral dislocations are extremely rare and probably do not exist without an anterior/posterior injury. Longitudinal traction may be all that is required for reduction. However, if the joint deviates considerably to either side, appropriate pressure over the medial or lateral aspects to align the elbow prior to reduction often facilitates reduction.77,85

Divergent Dislocation

This is an extremely rare type of dislocation that results from tearing of the interosseous membrane. Although I have never treated one of these dislocations, medial and lateral pressure over the divergent radius and ulna to align the forearm bone before reducing it as a simple posterior dislocation has been described.75,81,96

COMPLICATIONS OF ELBOW DISLOCATION

Joint Stiffness

As in adults, joint stiffness is the most common problem encountered after dislocation of the elbow in children. The child and his or her parents must be advised that joint motion may be lost as a result of the injury. In older children, fully complete extension may never be recovered, although the loss of the last 5 to 10 degrees of extension is not accompanied by any marked functional deficit. Elbows in children should not be immobilized longer than 4 weeks, and exercises after injury should be primarily active; passive motion should be avoided. Seldom is manipulation or passive physiotherapy required for joint stiffness after a dislocation of the elbow; this type of treatment often delays recovery because it is accompanied by further joint irritation, capsular tearing, and hematoma formation. A year may be required to regain full motion in the child’s elbow, the child being his or her own best physiotherapist. Management of the stiff elbow in the child is discussed in detail in Chapter 21.

Myositis Ossificans

Myositis ossificans is an uncommon complication of a simple dislocation of the elbow joint in children unless it is accompanied by a crush injury, head injury, major trauma, or multiple manipulations. Myositis ossificans may bridge the joint involving the brachialis muscle. The ossific lesion can be excised once it is mature, however, but recurrence is still possible.110

Nerve Injuries

Nerve injuries are uncommon in simple posterior elbow dislocations in children. The ulnar nerve is most frequently involved.80,117 The common posterolateral dislocation of the elbow results in a stretch on the ulnar nerve. The median and, rarely, the radial nerves also may suffer neuropraxic injuries secondary to posterior dislocation of the elbow.

The median nerve may be vulnerable to entrapment within the joint subsequent to reduction of the elbow dislocation. Although rare, this type of entrapment has been reported only in children, and diagnosis is frequently delayed. It should be suspected when signs of median nerve injury or pain accompany avulsion of the medial epicondyle; in such instances, the nerve usually lies “posterior” to the medial epicondyle (Fig. 20-29).98,102,105,108

FIGURE 20-29 Course of median nerve lying entrapped posterior to the medial epicondyle.

(Redrawn from Matev, I.: Radiological sign of entrapment of the median nerve in the elbow joint after posterior dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 58:353, 1976.)

As emphasized by Green,101 in an excellent review of this subject, persistent pain or increasing median nerve dysfunction should alert one to the possibility of nerve entrapment. A late clinical sign of entrapment is persistent limitation of elbow motion; a late radiologic sign of median nerve entrapment is depression of the cortex of the distal humerus just proximal to the medial epicondyle, where the median nerve passes behind the humerus.105,106 This is termed Matev’s sign (Fig. 20-30). Immediate exploration should be undertaken once the diagnosis of nerve entrapment has been made. If the nerve is functionally intact, as demonstrated by nerve stimulation, simple removal of the nerve from the joint is sufficient treatment. If the nerve is obviously severely damaged, crushed, or scarred and nonfunctional, resection of the damaged section with end-to-end reanastomosis is recommended.99,107

Vascular Injury

Injury to the brachial artery to the extent of complete occlusion is not commonly observed in dislocations of the elbow in children. The brachial artery may be stretched over the distal humerus, and if the force is sufficient, damage to the artery may occur. This is evident by the usual signs of vascular impairment, which then demand exploration of the artery. The elbow should always be reduced before making a final assessment of the vascular status of the limb because it simply may be occluded subsequent to the elbow deformity.100,103,104,106

Recurrent Dislocation of the Elbow

Recurrent dislocation of the elbow in children is very uncommon, as is an unreduced dislocation.69 Today, recurrent dislocation is known to occur with a deficient lateral ulnar collateral ligament.93 Inadequate treatment, in which the elbow has been kept flexed at less than 90 degrees, especially when associated with a fracture of the coronoid process, may result in redislocation of the elbow and reinjury and recurrent dislocation.111–121

It is uncommon to experience recurrent dislocation. Uncommonly, this may be secondary to severe generalized ligamentous laxity, as occurs in Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. In a review of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome by Beighton and Horan,111 19 of 100 patients suffered dislocations of one or more joints, with three having dislocation of the elbow. Recurrent dislocations of the elbow were reported by Rames and Strecker120 in a 9-year-old girl who subsequently required a repair of the lateral capsule and ligamentous structures with drill holes through the lateral epicondyle to firmly anchor the capsule, as described by Osborn and Cotterill.119

Recurrent subluxation of the elbow recently was described by O’Driscoll and Morrey,118 who noted the etiology as deficiency of the lateral ulnar collateral ligament. Of note, like the shoulder, recurrence of the elbow dislocation is greater in adolescents than in adults. This may be treated successfully with an orthosis designed to block the last 15 degrees of extension associated with muscle strengthening to protect and stabilize the elbow. If this fails, surgery to reconstruct the lateral collateral ligament complex is required.

TRAUMATIC DISLOCATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD

1 Beddow F.H., Corckery P.H. Lateral dislocation of the radial humeral joint with greenstick fracture of the upper end of the ulna. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1960;42B:782.

2 De Lee J.C. Transverse divergent dislocation of the elbow in a child. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:322.

3 Heidt R.S., Stern P.J. Isolated posterior dislocation of the radial head. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1982;168:136.

4 Hudson D.A., DeBeer De.V. Isolated traumatic dislocation of the radial head in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68B:378.

5 Kirkos J.M., Beslikas T.A., Papavasiliou V.A. Posteromedial dislocation of the elbow with lateral condylar fracture in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 2003;408:232.

6 Lincoln T.L., Mubarek S.J. “Isolated” traumatic radial head dislocation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1994;14:454.

7 Macias C.G., Wiebe R., Bothner J. History and radiographic findings associated with clinically suspected radial head subluxations. Pediatr. Emerg. Care. 2000;16:22.

8 Pudas T., Hurme T., Mattila K., Svedstrom E. Magnetic resonance imaging in pediatric elbow fractures. Acta Radiol. 2005;46:636.

9 Schubert J.J. Dislocation of the radial head in the newborn infant. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47A:1010.

10 Stelling F.H., Cote R.H. Traumatic dislocation of the head of the radius in children. J. A. M. A. 1956;160:732.

11 Storen G. Traumatic dislocation of the radial head as an isolated lesion in children. Acta Clin. Scand. 1958;116:144.

12 Vesely D.G. Isolated traumatic dislocation of the radial head in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1967;50:31.

13 Wiley J.J., Pegington J., Horwich J.P. Traumatic dislocation of the radius at the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56B:501.

14 Wright P.R. Greenstick fractures of the upper end of the ulna with dislocation of the radial humeral joint or displacement of the superior radial epiphysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45B:727.

15 Yates C., Sullivan J.A. Arthrographic diagnosis of elbow injuries in children. Pediatr. Orthop. 1987;7:54.

16 Zivkovic T. Traumatic dislocation of the radial head in a 5-year-old boy. J. Trauma. 1978;18:289.

DEVELOPMENTAL DISLOCATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD

17 Cummings R.J., Jones E.T., Reed F.E., Mazur J.M. Infantile dislocation of the elbow complicating obstetric palsy. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1996;16:589.

18 De Boeck H. Treatment of chronic isolated radial head dislocation in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 2000;380:215.

19 Hirayama T., Takemitsu Y., Yagihara K., Mikita A. Operation for chronic dislocation of the radial head in children. Reduction by osteotomy of the ulna. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69:639.

20 Lloyd-Roberts G.C., Bucknill T.M. Anterior dislocation of the radial head in children-etiology. Natural history and management. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59B:402.

21 Pletcher D., Hofer M.M., Koffman D.M. Non-traumatic dislocation of the radial head in cerebral palsy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:104.

22 Peeters R.L.M. Radiological manifestations of the Cornelia de Lange syndrome. Pediatr. Radiol. 1975;3:41.

23 Salama R., Weintroub S., Weissman S.L. Recurrent dislocation of the radial head. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1977;125:156.

24 Silberstein M.J., Brodeur A.E., Graviss E.R. Some vagaries of the radial head and neck. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:1153.

25 Southmayd W., Parks J.C. Isolated dislocation of the radial head without fracture of the ulna. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1973;97:94.

26 Subbarao J.V., Kumar V.N. Spontaneous dislocation of the radial head in cerebral palsy. Orthop. Rev. 1987;16:457.

CONGENITAL DISLOCATION OF THE RADIAL HEAD

27 Almquist E.E., Gordon L.H., Blue A.I. Congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51A:1118.

28 Bell S.N., Morrey B.F., Bianco A.J.Jr. Chronic posterior subluxation and dislocation of the radial head. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73:392.

29 Carevias D.E. Some observations on congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39B:86.

30 Cockshott W.P., Omololu A. Familial posterior dislocation of both radial heads. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1958;40B:484.

31 Gattey P.H., Wedge J.H. Unilateral posterior dislocation of the radial head in identical twins. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989;6:220.

32 Gunn D.R., Pilley V.K. Congenital dislocation of the head of the radius. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1964;84:108.

33 Kelikian H., editor. Dislocation of the radial head. Congenital Deformities of the Hand and Forearm. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1974;902.

34 Kelly D.W. Congenital dislocation of the radial head: spectrum and natural history. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1981;1:295.

35 Mardam-Bey T., Ger E. Congenital radial head dislocation. J. Hand Surg. 1979;4:316.

36 Mital M.A. Congenital radial ulnar synostosis and congenital dislocation of the radial head. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1976;7:375.

37 Miura T. Congenital dislocation of the radial head. J. Hand Surg. 1990;15B:477.

38 Mizuno K., Usui Y., Kohyama K., Hirohata K. Familial congenital unilateral anterior dislocation of the radial head: differentiation from traumatic dislocation by means of arthrography. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:1086.

MONTEGGIA FRACTURE-DISLOCATION OF THE ELBOW IN CHILDREN

39 Bado J.L. The Monteggia lesion. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1967;50:71.

40 Boyd H.B., Boals J.C. The Monteggia lesion: a review of 159 cases. Clin Orthop. 1969;66:94.

41 Bruce H.E., Harvey J.P.W., Wilson J.C.Jr. Monteggia fractures. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56A:1563.

42 Bell-Tawse A.J.F. The treatment of malunited anterior Monteggia fractures in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1965;47B:718.

43 Cappellino A., Wolfe S.W., Marsh J.S. Use of a modified Bell Tawse procedure for chronic acquired dislocation of the radial head. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1998;18:410.

44 Dormans J.P., Rang M. The problem of Monteggia fracture dislocations in children. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1990;21:251.

45 Evans E.M. Pronation injuries of the forearm with special reference to the anterior Monteggia fracture. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1949;31B:578.

46 Fahmy N.R.M. Unusual Monteggia lesions in children. Injury. 1981;12:399.

47 Freedman L., Luk K., Leong J.C. Radial head reduction after a missed Monteggia fracture: brief report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70:846.

48 Hume A.C. Anterior dislocation of the head of the radius associated with undisplaced fracture of the olecranon in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39B:508.

49 Hurst L.C., Dubrow E.N. Surgical treatment of symptomatic chronic radial head dislocation: a neglected Monteggia fracture. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1983;3:227.

50 Kalamchi A. Monteggia fracture dislocation in children. Late treatment in two cases. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1986;68:615.

51 Letts M., Locht R., Weins J. Monteggia fracture dislocations in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67:724.

52 Mullick S. The lateral Monteggia fracture. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1977;59A:543.

53 Olney B.W., Menelaus M.B. Monteggia and equivalent lesions in childhood. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989;9:219.

54 Ovesen O., Brok K.E., Arreskov J., Bellstrom T. Monteggia lesions in children and adults: an analysis of etiology and long-term results of treatment. Orthopedics. 1990;13:529.

55 Papavasiliou V.A., Nenopoulos S.P. Monteggia-type elbow fractures in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1988;233:230.

56 Peterson, H. A., and Seel, M. J.: Management of post-traumatic chronic radial head dislocation in children. Presented at the 1998 Annual Meeting of the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America, Cleveland, Ohio, May 7, 1998.

57 Ravessoud F.A. Lateral condylar fracture and ipsilateral ulnar shaft fracture: Monteggia equivalent lesions. J. Pediatr. Orthop.. 1985;5:364.

58 Ring D., Waters P.M. Operative fixation of Monteggia fractures in children. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1996;78B:734.

59 Spinner M., Freundlich B.D., Teicher J. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy as a complication of Monteggia fractures in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res.. 1968;58:141.

60 Stein F., Grabias S.L., Deffer P.A. Nerve injuries complicating Monteggia lesions. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53A:1432.

61 Theodorou S.D. Dislocation of the head of the radius associated with fractures of the upper end of the ulna in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51B:70.

62 Tompikins D.G. The anterior Monteggia fracture. Observations on etiology and treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53A:1009.

63 Wang M.N., Chang W.N. Chronic posttraumatic anterior dislocation of the radial head in children: thirteen cases treated by open reduction, ulnar osteotomy, and annular ligament reconstruction through a Boyd incision. J. Orthop. Trauma. 2006;20:1.

64 Wiley J.J., Galey J.P. Monteggia injuries in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;69B:728.

65 Wright P.R. Greenstick fracture of the upper end of the ulna with dislocation of the radiohumeral joint or displacement of the superior radial epiphysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1963;45B:727.

ACUTE DISLOCATION OF THE ELBOW IN CHILDREN

66 Aitken A.P., Childress H.M. Inter-articular displacement of the internal epicondyle following dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1938;20:161.

67 Aufranc O.E., Jones W.M., Turner R.H., Thomas W.H. Dislocation of the elbow with fracture of the radial head and distal radius. J. A. M. A. 1967;202:131.

68 Beghin J.L., Bucholz R.W., Wenger D.R. Intracondylar fractures of the humerus in young children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:1083.

69 Bilett D.M. Unreduced posterior dislocation of the elbow. J. Trauma. 1979;19:186.

70 Blatz D.J. Anterior dislocation of the elbow in a case of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Orthop. Rev. 1981;10:129.

71 Bulut G., Erken H.Y., Tan E., Ofluolu O., Yildiz M. Treatment of medial epicondyle fractures accompanying elbow dislocations in children. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2005;39:334.

72 Caravias D.E. Forward dislocation of the elbow without fracture of the olecranon. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1957;39B:334.

73 D’Ambrosia R., Zink W. Fractures of the elbow in children. Pediatr. Ann. 1982;11:541.

74 Davidson R.S., Markowitz R.I., Dormans J., Drummond D.S. Ultrasonographic evaluation of the elbow in infants and young children after suspected trauma. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1994;76A:1804.

75 De Lee J.C. Transverse divergent dislocation of the elbow in a child. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:322.

76 De Lee J.C., Wilkens K.E., Rogers K.F., Rockwood C.A. Fracture separation of the distal humeral epiphysis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:46.

77 Eppright R.H., Wilkins K.E.. Fractures and dislocations of the elbow. Rockwood C.A.Jr., Green D.P., editors. Fractures, Vol. 1. J. B. Lippincott Co., Philadelphia, 1975;487.

78 Fowles J.V., Slimane N., Kassab M.T. Elbow dislocation with avulsion of the medial humeral epicondyle. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72:102.

79 Grantham S.A., Tietjen R. Transcondylar fracture-dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58A:1030.

80 Heilbronner D.M., Manili A., Little R.E. Elbow dislocation during overhead skeletal traction therapy. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1981;147:185.

81 Holbrook J.L., Green N.E. Divergent pediatric elbow dislocation. A case report. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1988;234:72.

82 Kaplan S.S., Reckling R.W. Fracture separation of the lower humeral epiphysis with medial displacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53A:1105.

83 Lee H.H., Shen H.C., Chang J.H., Lee C.H., Wu S.S. Operative treatment of displaced medial epicondyle fractures in children and adolescents. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14:178.

84 Lejman T., Kowalczyk B., Felu J. Does coexistent fractures impair the results of treatment of elbow dislocations in children? Chir. Narzadow Ruchu Ortop Pol. 2006;71:137.

85 Linscheld R.L., Wheeler D.K. Elbow dislocations. J. A. M. A. 1965;194:1171.

86 McAuliffe T.B., Williams D. Transverse divergent dislocation of the elbow. Injury. 1988;19:279.

87 Meyn M.A.Jr., Quibley T.B. Reduction of posterior dislocation of the elbow by traction on the dangling arm. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1974;103:106.

88 Oury J.H., Roe R.D., Laning R.C. A case of bilateral anterior dislocations of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1972;12:170.

89 Patrick J. Fracture of the medial epicondyle with displacement into the elbow joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1946;28:143.

90 Protzman R.R. Dislocation of the elbow joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1978;60A:539.

91 Rang M. Children’s Fractures. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Co., 1983.

92 Rasool M.N. Dislocations of the elbow in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2004;86B:1050.

93 Schwab G.H., Bennett J.B., Woods G.W., Tollos H.S. Biomechanics of elbow instability—the medial collateral ligament. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1980;146:42.

94 Smith F.M. Children’s elbow injuries: fractures and dislocations. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1967;50:7.

95 Smith F.M. Displacement of the medial epicondyle of the humerus into the elbow joint. Ann. Surg. 1946;124:410.

96 Sovio O.M., Tredwell S.J. Divergent dislocation of the elbow in a child. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1986;6:96.

97 Tachdjian M.O.. Pediatric Orthopaedics, Vol. 2. W. B. Saunders Co., Philadelphia, 1972;1604.

COMPLICATIONS OF DISLOCATION OF THE ELBOW IN CHILDREN

98 Boe S., Holst-Neilson F. Intra-articular entrapment of the median nerve after dislocation of the elbow. J. Hand Surg. 1987;12:356.

99 Floyd W.E.3rd, Gebhardt M.C., Emans J.B. Intra-articular entrapment of the median nerve after elbow dislocation in children. J. Hand Surg. 1987;12:704.

100 Grimer R.J., Brooks S. Brachial artery damage accompanying closed posterior dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1985;67:378.

101 Green N.E. Entrapment of the median nerve following elbow dislocation. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1983;3:384.

102 Hallet J. Entrapment of the median nerve after dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63B:408.

103 Kerian R. Elbow dislocation and its association with vascular disruption. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51:756.

104 Louis D.S., Ricciardi J., Sprengler D.M. Arterial injuries: a complication of posterior elbow dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1974;56A:1631.

105 Matev I. A radiological sign of entrapment of the median nerve in the elbow joint after posterior dislocation. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1976;58B:353.

106 Noonan K.J., Blair W.F. Chronic median-nerve entrapment after posterior fracture-dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77A:1572.

107 Rubens M.K., Aulicino P.L. Open elbow dislocation with brachial artery disruption: a case report and review of the literature. Orthopaedics. 1986;9:539.

108 Stiger R.N., Larrick R.D., Meyer T.F. Median nerve entrapment following elbow dislocations in children. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51A:381.

109 Tayob A.A., Shively R.A. A bilateral elbow dislocation with inter-articular displacement of medial epicondyle. J. Trauma. 1980;20:332.

110 Thompson H.C., Garcia A. Myositis ossificans after massive elbow injuries. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1967;50:129.

RECURRENT DISLOCATION OF THE ELBOW IN CHILDREN

111 Beighton P., Horan F. Orthopaedic aspects of the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1969;51B:444.

112 Hall R.M. Recurrent posterior dislocation of the elbow joint in a boy. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1953;35B:56.

113 Hassmann G.C., Brunn F., Neer C.S. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1975;57A:1080.

114 Hening J.A., Sullivan J.A. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow. J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1989;9:483.

115 Jacobs R.L. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow: a case report and review of the literature. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1971;74:151.

116 Mantle J. Recurrent posterior dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:590.

117 Morrey B.F. Complex instability of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1997;79A:460.

118 O’Driscoll S.W., Bell D.F., Morrey B.F. Posterolateral rotatory instability of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73A:440.

119 Osborne G., Cotterill P. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1966;48B:340.

120 Rames R.D., Strecker W.B. Recurrent elbow dislocations in a patient with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. Orthopaedics. 1991;14:707.

121 Trias A., Comeau Y. Recurrent dislocation of the elbow in children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1974;100:74.

122 Amir D., Frank J., Pogrund H. Pulled elbow and hypermobility of joints. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1990;257:94.

123 Boyette D.P., Ahoski H.C., London A.H.Jr. Subluxation of the head of the radius-“nursemaid’s elbow.”. J. Pediatr.. 1948;32:278.

124 Choung W., Heinrich S.D. Acute annular ligament interposition into the radiocapitellar joint in children (nurse maid’s elbow). J. Pediatr. Orthop. 1995;15:454.

125 Hart G.M. Subluxation of the head of the radius in young children. J.A.M.A. 1969;169:1734.

126 Magill H.K., Aitken A.P. Pulled elbow. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 1954;98:753.

127 Mehta L. Subluxation of radial head in children with reference to radial head and neck diameters. J. Ind. Med. Assoc. 1972;166:220.

128 Nussbaum A.J. The off-profile proximal radial epiphysis: another potential pitfall in the x-ray diagnosis of elbow trauma. J. Trauma. 1983;23:40.

129 Salter R.B., Zaltz C. Anatomic investigations of the mechanism of injury and pathologic anatomy of “pulled elbow” in young children. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1971;77:141.