Nutritional assessment is an important initial step in nursing care and preventive health care. It aids in identifying eating practices, misconceptions, and symptoms that can lead to nutritional problems and eating disorders, including obesity, anorexia nervosa, and bulimia nervosa. Because the nurse often has continued contact with the parents and child, the nurse can often influence dietary practices.

Establishing Weight

Weight measurement is plotted on a growth chart (see Appendix B). Weight usually remains within the same percentile from measurement to measurement. Sudden increases or decreases should be noted. Average weight and height increases for each age are summarized in Table 7-1.

| Age | Weight | Height |

|---|---|---|

| 0 to 6 months |

Average weekly gain 140–200 gm (5–7 oz)

Birth weight doubles by 4–6 months

|

Average monthly gain 2.5 cm (1 in) |

| 6 to 18 months |

Average weekly gain 85–140 gm (3–5 oz)

Birth weight triples by 1 year

|

Average monthly gain 1.25 cm (0.5 in) |

| 18 months to 3 years | Average yearly gain 2–3 kg (4.4–6.6 lb) | Height at 2 years approximately half of adult height |

| 1 to 2 years | Average gain 12 cm (4.8 in) | |

| 2 to 3 years | Average gain 6–8 cm (2.4–3.2 in) | |

| 3 to 6 years | Average yearly gain 1.8–2.7 kg (4–6 lb) | Yearly gain 6–8 cm (2.4–3.2 in) |

| 6 to 12 years | Average yearly gain 1.8–2.7 kg (4–6 lb) | Yearly gain 5 cm (2 in) |

| Girl, 10 to 14 years | Average gain 17.5 kg (38.5 lb) |

95% of adult height achieved by onset of menarche

Average gain 20.5 cm (8.2 in)

|

| Boy, 12 to 16 years | Average gain 23.7 kg (52.1 lb) |

95% of adult height achieved by 15 years

Average gain 27.5 cm (11 in)

|

| Measurements Related to Weight | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|

| Weight | |

| Infants (1 to 12 Months) | |

|

Undress completely (including diaper) and lay on a balance infant scale. Protect the scale surface with a cloth or paper liner and zero the scale with the liner before weighing the infant.

Place hand lightly above the infant for safety. If precise measurements are required, have a second nurse perform an independent measurement. If there is a difference between the two measurements, a third one should be performed. For reliability in making comparisons, it is important to use the same scale, at the same time of day, for subsequent weight measurements.

|

Breastfed infants tend to display slower growth than bottle-fed infants, especially in the second half of the first year. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Weight loss or failure to gain weight might be related to dehydration, acute infections, feeding disorders, malabsorption, chronic disease, neglect, excessive ingestion of apple and pear juices, thyroid disorders, ectodermal dysplasias, diabetes, anorexia nervosa, cocaine use by mother in prenatal period, fetal alcohol syndrome, tuberculosis, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). A loss of 10% on a growth chart is indicative of severe weight loss. Excessive weight gain might be related to chronic renal, pulmonary, or cardiovascular disorders or to endocrine dysfunction. Children who are 120% or more of ideal body weight for height and age are considered obese. | |

| Measurements Related to Weight | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|

| Toddlers and Preschoolers (12 Months to 6 Years) | |

| Undress, except for underpants, and weigh on a standing balance scale. (Children younger than 2 years are weighed on an infant or sitting scale unless they can stand well.) | |

| Older Children (6 Years and Older) | |

| Remove shoes. Weigh clothed, on a standing scale. | Clinical Alert |

| Marked weight loss is often an initial sign of Type I diabetes. A body weight of less than 85% of the expected norm in adolescents might signal anorexia nervosa, especially if bradycardia, cold intolerance, dry skin, brittle nails, body distortion, and preoccupation with food are present. Weight loss can also accompany amphetamine use or changes in living conditions (e.g., homelessness). |

| Measurements Related to Weight | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|

| BMI | |

|

Body mass index (BMI) indicates body composition and is a valuable indicator of the degree of overweight or obesity and of underweight. BMI takes into account the child’s height and weight and can be calculated through the following formula:

|

See Appendix B for BMI age charts. |

| Skinfold Thickness | |

| Skinfold thickness is a more reliable indicator of body fat than weight because the majority of fat is stored in subcutaneous tissues. Measurements, as indicators of body fat, must be treated cautiously as findings will vary with experience and familiarity of assessor with technique. To measure skinfold thickness, use calipers such as Lange calipers. The most common sites for measurement are triceps and subscapular regions. For triceps, have child flex arm 90 degrees at elbow and mark midpoint between acromion and olecranon on the posterior aspect of the arm. Gently grasp fold of child’s skin 1 cm (0.4 inch) above this midpoint. Gently pull fold away from muscle and continuing to hold, place caliper jaws over midpoint. Estimate reading to nearest 1.0 mm, 2 to 3 seconds after applying pressure. Take measurements until two agree within 1 mm. | Clinical Alert |

| Obesity might be indicated by skinfold thickness greater than or equal to 85% for triceps measurement (see Appendix B). | |

| Measurement of Height/Length | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|

| Infants/Toddlers (1 to 24 Months) | |

| Lay infant flat. Have parent hold infant’s head as the infant’s legs are extended and pushed gently toward the table. Measure the distance between marks made indicating heel tips (with toes pointing toward the deficiency, ceiling) and vertex of head. Do not use a cloth tape for measurement because it can stretch. If using a measuring board or tray, align the infant’s head against the top bar and ask the parent to secure the infant’s head there. Straighten the infant’s body and, while holding the feet in a vertical position, bring the footboard snugly up against the bottoms of the feet. |

Clinical Alert

Although short stature is usually genetically predetermined, it can also indicate chronic heart or renal disease, growth hormone deficiency, malnutrition, Kearns-Sayre syndrome, Turner’s syndrome, dwarfism, methadone exposure, or fetal alcohol syndrome.

|

| Measurement of Height/Length | Significance of Findings |

|---|---|

| Use the same technique to obtain subsequent height measurements. | |

| Children (24 Months and Older) | |

|

Have child, in stocking feet or bare feet, stand straight on a standard scale. Measure with the attached marker, to the nearest 0.1 cm (0.03 inch).

If a scale with a measuring bar is not available or if a child is afraid of standing on the scale’s base, have the child stand erect against a wall. Place a flat object, such as a clipboard, on the child’s head, at a right angle to the wall. Read the height at the point where the flat object touches the measuring tape or the wall-mounted unit (stadiometer).

|

Height is usually less in the afternoon than in the morning. Correct for this tendency by placing slight upward pressure under the jaw. |

Assessment of nutrition, feeding, and eating practices requires sensitivity on the part of the nurse. Eating practices are highly personal, as well as cultural, and can be more accurately assessed after a rapport has been established. Guilt, apprehension, and the parent’s desire to give the “right” responses can alter the accuracy of the assessment. Table 7-2 lists typical eating habits for various age groups. Table 7-3 lists assessment findings that are associated with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, and Table 7-4 describes physical assessments and findings associated with nutrition.

| Age Group | Eating Practices | Concerns Arising from Eating Practices | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants/toddlers (1 to 12 months) |

Formula or breast milk forms major part of diet for first 6 months and is generally recommended until 1 year.

Solid foods assume greater importance in second 6 months of life. By 1 year, infant is able to eat all solid foods unless food intolerance develops. White grape juice is a healthy form of juice. Juice intake should be limited to no more than 150 ml per day in infants.

|

Mothers might feed child in accordance with practices followed in their own upbringing.

Early introduction of solid foods (before 5 or 6 months) can contribute to allergies.

Sensitivity to cow’s milk might be suggested by colic, sleeplessness, diarrhea, abdominal pain, chronic nasal discharge, recurrent respiratory ailments, eczema, pallor, or excessive crying.

Colic, regurgitation, diarrhea, constipation, bottle mouth syndrome, and rashes are common concerns associated with infant feeding.

Yellowish skin coloration might accompany persistent feeding of carrots.

Excess milk intake in later infancy might lead to milk anemia.

Excessive ingestion of pear and apple juices can be associated with failure to thrive, tooth decay, diarrhea, and obesity.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Toddlers/preschool-age children (12 months to 6 years) |

Appetites tend to be erratic because of sporadic energy needs.

Appetites of toddlers and preschoolers are smaller than those of infants because of slowed growth. Toddlers and preschoolers have definite likes and dislikes. Likes include foods such as yogurt, fruit drinks, fruit breads, and cookies that are easy to eat and to handle. Dislikes include casseroles, liver, and cooked vegetables. Food is often consumed “on the go.”

Children might go on “food jags,” in which one food is preferred for a few days.

Variety is desirable, but not necessary as long as the child eats from all food groups during the course of a day.

|

Some children snack their way through the day and rarely consume a regular meal.

Excessive intake of drinks (e.g., milk, juices, water, carbonated beverages) might result in reduced appetite for other foods.

Mealtimes might become a battle between parents and toddlers over types and amounts of food eaten.

Parents might express concern over toddlers’ or preschoolers’diminished appetite.

80% of children with both parents obese are likely to be obese. It is recommended that children by 2 years of age receive baseline screening for cardiovascular disease factors such as parental obesity, age and weight, and blood pressure measurements.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| School-age children (6 to 12 years) |

Children generally have a good appetite and like variety. Plain foods still preferred.

Increasing numbers of activities compete with mealtimes.

Television and peers influence food choices.

|

Parents might express concern over table manners.

A child is considered overweight when weight is equal to or exceeds the 85th percentile.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Adolescents (12 years and older) | Food habits include skipping meals (especially breakfast), consuming carbonated drinks and fast foods, snacking, and unusual food choices. |

Alcohol might form a substantial portion of caloric intake.

Preoccupation with food and feelings of guilt might be indicative of eating disorders. Anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa are serious disorders related to an obsession with losing weight (see Table 7-3 for assessment findings associated with common eating disorders).

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Adolescents consume increasingly larger amounts of alcohol at younger ages.

Adolescent girls frequently are calorie conscious and might diet, thus severely restricting their calcium intake.

|

Low calcium intake might place adolescent females at risk for osteoporosis. |

| Body Area | Signs of Adequate/Appropriate Nutrition | Signs of Inadequate/Inappropriate Nutrition | Possible Causes of Inadequate/Inappropriate Nutrition |

|---|---|---|---|

| General growth | Height, weight, head circumference within 5th and 95th percentiles | Height, weight, head circumference below or above 5th and 95th percentiles | Protein, fats, vitamin A, niacin, calcium, iodine, manganese, zinc deficiency/excess |

| Sexual development age appropriate | Delayed sexual maturation | Less than expected growth possibly related to disease (especially endocrine dysfunction) or to genetic endowment | |

| Vitamin A or D excess | |||

| Skin | Elastic, firm, slightly dry; no lesions, rashes, hyperpigmentation | Dryness | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Essential and unsaturated fatty acid deficiency | |||

| Swollen red pigmentation (pellagrous dermatosis) | Niacin deficiency | ||

| Hyperpigmentation | Vitamin B12, folic acid, niacin deficiency | ||

| Edema | Protein deficiency or sodium excess | ||

| Poor skin turgor | Water, sodium deficiency | ||

| Petechiae | Ascorbic acid deficiency | ||

| Delayed wound healing | Vitamin C deficiency | ||

| Decreased subcutaneous tissue | Prolonged caloric deficiency | ||

| Pallor | Iron, vitamin B12 or C, folic acid, pyridoxine deficiency | ||

| Hair | Shiny, firm, elastic | Dull, dry, thin, brittle, sparse, easily plucked | Protein, caloric deficiency |

| Alopecia | Protein, caloric, or zinc deficiency | ||

| Head | Head evenly molded, with occipital prominence; facial features symmetric | Skull flattened, frontal bones prominent | Vitamin D deficiency |

| Sutures fused by 12 to 18 months | Suture fusion delayed | Vitamin D deficiency | |

| Hard, tender lumps in occipital region | Vitamin A excess | ||

| Headache | Thiamine excess | ||

| Neck | Thyroid gland not obvious to inspection, palpable in midline | Thyroid gland enlarged, obvious to inspection | Iodine deficiency |

| Eyes | Clear, bright, shiny | Dull, soft cornea; white or gray spots on cornea (Bitot’s spots) | Vitamin A deficiency |

| Membranes pink and moist | Pale membranes | Iron deficiency | |

| Burning, itching, photophobia | Riboflavin deficiency | ||

| Night vision adequate | Night blindness | Vitamin A deficiency | |

| Redness, fissuring at corners of eyes | Riboflavin, niacin deficiency | ||

| Nose | Smooth, intact nasal angle | Cracks, irritation at nasal angle | Niacin deficiency, vitamin A excess |

| Lips | Smooth, moist, no edema | Angular fissures, redness, and edema | Riboflavin deficiency, vitamin A excess |

| Tongue | Deep pink, papillae visible, moist, taste sensation, no edema | Paleness | Iron deficiency |

| Red, swollen, raw | Folic acid, niacin, vitamin B or B12 deficiency | ||

| Magenta coloration | Riboflavin deficiency | ||

| Diminished taste | Zinc deficiency | ||

| Gums | Firm, coral color | Spongy, bleed easily, receding | Ascorbic acid deficiency |

| Teeth | White, smooth, free of spots or pits | Mottled enamel, brown spots, pits | Fluoride excess, or discoloration from antibiotics |

| Defective enamel | Vitamin A, C, or D, or calcium or phosphorus deficiency | ||

| Caries | Carbohydrate excess, poor hygiene | ||

| Cardiovascular system | Pulse and blood pressure within normal limits for age | Palpitations | Thiamine deficiency |

| Rapid pulse | Potassium deficiency | ||

| Arrhythmia | Niacin, potassium excess; magnesium, potassium deficiency | ||

| High blood pressure | Sodium excess | ||

| Decreased blood pressure | Thiamine deficiency | ||

| Gastrointestinal system | Bowel habits normal for age | Constipation | Calcium excess, overrigid toilet training, inadequate intake of high-fiber foods or fluids |

| Diarrhea | Niacin deficiency; vitamin C excess; high consumption of fresh fruit, other high-fiber foods, excessive consumption of juices | ||

| Musculoskeletal system | Muscles firm and well developed, joints flexible and pain free, extremities symmetric and straight, spinal nerves normal |

Muscles atrophied, dependent edema

Knock-knee, bowleg, epiphyseal enlargement

Bleeding into joints, pain

Beading on ribs

|

Protein, caloric deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency; disease processes

Vitamin C deficiency

Vitamins C and D deficiency

|

| Neurologic system | Behavior alert and responsive, intact muscle innervation | Listlessness, irritability, lethargy | Thiamine, niacin, pyridoxine, iron, protein, caloric deficiency |

| Tetany | Magnesium deficiency | ||

| Convulsions | Thiamine, pyridoxine, vitamin D, calcium deficiency, phosphorus excess | ||

| Unsteadiness, numbness in hands and feet | Pyridoxine excess | ||

| Diminished reflexes | Thiamine deficiency |

General Assessment

▪ Is your child on a special diet?

▪ Are there any suspected or known food allergies?

▪ Describe your child’s typical intake over 24 hours (what child ate for each meal and between meals).

▪ Has your child lost or gained weight recently?

▪ Does your family eat together?

▪ Do any cultural, ethnic, or religious influences affect your child’s diet? How?

▪ Do you have any concerns?

▪ How much weight did you (mother) gain during pregnancy?

▪ What was your infant’s birth weight? When did it double? Triple?

▪ What vitamin supplements does your infant receive?

▪ Do you give your infant extra fluids such as juice or water?

▪ How often does your infant wake at night? What kinds of things do you do to comfort at night (e.g., introduction of solid or table foods earlier than anticipated to help the infant sleep through the night)?

▪ At what age did you start cereals, vegetables, fruits, meat (or other sources of proteins), table foods, and finger foods?

▪ Does your infant spit up frequently? What are his or her stools like?

▪ Does your infant have any problems with feeding (e.g., lethargy, poor sucking, regurgitation, colic, irritability, rash, diarrhea)?

▪ Breastfed infants:

How long does your infant feed at one time?

Do you alternate breasts?

How do you recognize that your infant is hungry? Full?

Describe your infant’s elimination and sleeping patterns.

Describe your usual daily diet.

Do you have concerns related to breastfeeding?

▪ Formula-fed infants:

What type of formula is your infant taking?

How do you prepare the formula?

What type of bottle does your infant take?

How many ounces (ml) of formula does your infant drink per day?

Do you prop or hold your infant while feeding?

Do you have concerns related to bottle feeding?

▪ What foods does your child prefer? Dislike?

▪ Does the child snack? If so, when? What foods are given as snacks? When are sweet foods eaten? Are foods used as rewards (e.g., “If you eat your vegetables, you can have dessert”)?

▪ What assistance does your child require with eating?

▪ What kinds of activities does your child enjoy? How many hours of television, video games, or computer usage does your child enjoy per day?

Assessment of Nutrition and Eating Practices of Adolescents

▪ What foods do you prefer? Dislike?

▪ What foods do you choose for a snack?

▪ Are you satisfied with the quantity and kinds of food you eat?

▪ Are you content with your weight? If not, have you tried to change your food intake? In what ways? Do you use skipping meals, diet pills, laxatives, or diuretics to lose weight? Have you ever eaten what others would regard as an unusually large amount of food? Have you ever made yourself vomit to get rid of food eaten?

▪ Have you started your menstrual periods (girls)? Are you taking an oral contraceptive?

▪ Are you active in sports or fitness activities? If so, are there any weight or food requirements (e.g., high protein intake, increased calories, weight restrictions or increases) associated with these activities?

▪ What exercise regimens do you follow?

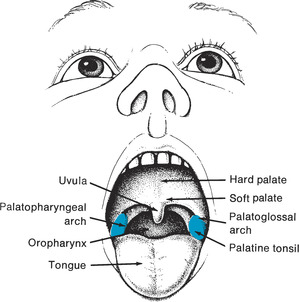

Assessment of Physical Signs of Nutrition or Malnutrition

Many of the assessments related to nutritional status can be combined with other areas of the physical assessment. Table 7-4 outlines the head-to-toe observations that provide information about a child’s nutritional status.

Related Nursing Diagnoses

Ineffective breastfeeding: related to knowledge deficit, nonsupportive partner, previous breast surgery, supplemental feeding, poor infant sucking reflex, maternal anxiety, interruption in breastfeeding, infant anomaly.

Ineffective infant feeding pattern: related to prematurity, anatomic abnormality, neurologic impairment.

Effective breastfeeding: related to gestational age greater than 34 weeks, normal oral structure, maternal confidence, basic breastfeeding knowledge, normal breast structure.

Altered nutrition, more than body requirements: related to early introduction of solids, reported or observed obesity in one or both parents, rapid transition across growth percentiles, use of food as reward or comfort measure, excessive intake.

Altered nutrition, less than body requirements: related to biologic, psychologic, or economic factors.

Risk for altered development: related to failure to thrive, inadequate nutrition.

Risk for altered growth: related to malnutrition, prematurity, maladaptive feeding behaviors, anorexia, insatiable appetite.

Altered parenting: related to lack of knowledge about child maintenance, unrealistic expectations for child, lack of knowledge about development, inability to recognize infant cues, illness.

Body image disturbance: related to psychosocial or biophysical factors, developmental changes.

Altered dentition: related to nutritional deficits, dietary habits, chronic vomiting.

Diarrhea: related to laxative abuse, malabsorption.

Constipation: related to insufficient fluid intake, insufficient fiber intake, poor eating habits, dehydration.

Perceived constipation: related to cultural or family beliefs, faulty appraisal.