Chapter 2. Dimensions of a History

The purposes and extent of the health interview vary with the nature of the health care contact. For example, in an emergency situation it is necessary to focus on the chief complaint and the details of past health care contacts. The prenatal and postnatal histories and the psychosocial dimensions can be left for later, unless they are the focus for the concern. When a child has repeated contacts with a health care facility, it is necessary only to update a health history if it has been completed on initial contact. The course of an interview must be modified to fit the situation and the setting. A home setting, for example, can include many distractions and will require adaptation to the family’s environment.

Generally, a direct interview is preferred for a health history, as it facilitates the building of a relationship between the family and the nurse and enables the nurse to make rich observations related to behavior, interactions, and environment. However, if an indirect method, such as a questionnaire, is used, then it is important to review the written responses and follow up any unusual responses with the family.

Guidelines for Interviewing Parents and Children

▪ Follow principles of communication during the interview (see Chapter 1).

▪ Before beginning the interview the nurse must thoroughly understand the purposes of the health history and of the questions that are asked.

▪ Explain the purpose of the interview, before starting, to the parents and to the child. Cooperation and sharing are more likely to occur if the parents understand that the questions facilitate better care for their child. For the adolescent, understanding the parameters of confidentiality can be crucial to what is shared.

▪ Write brief notations about specific details. Do not try to write finished sentences and keep writing to a minimum. The flow of contact is lost if the nurse spends an extended amount of time writing or staring at a form. Further, the nurse might miss important opportunities to observe behaviors and family interactions if overly committed to recording during the interview.

▪ Know what information is necessary so that the parents and child are not asked for the same type of information repeatedly. Repeat questions only if further clarification is desired.

▪ Give broad openings at the beginning of the interview, such as, “Tell me why you came to see me today.” Use direct questions, such as, “Are the stools watery?” to assist the parent to focus on specific details.

▪ Do not interrupt the parent, child, or parent and interpreter.

▪ Accept what is being said. Nodding, reestablishing eye contact, or saying “uh-huh” provides encouragement to continue. If parents have difficulty recalling specific details (e.g., when specific developmental milestones were achieved), move on to other areas in the history. When this happens, it is important not to make the parents feel that they are “bad parents” because they are unable to remember.

▪ If an interpreter is being used, avoid commenting about the family in the presence of the family.

▪ Listen, and attend to nonverbal cues. The presenting complaint might have little to do with the real concern.

▪ Convey empathy and an unhurried attitude. Sit at eye level, if possible. If the family is from another culture, observe to determine what behaviors are acceptable and therefore empathic to them. Eye contact, for example, is considered disrespectful in some cultures (e.g., Native Americans) rather than indicative of active listening and empathy.

▪ Integrate the child when possible and when culturally appropriate. Even the very young can answer the question “What do you like to eat?”

▪ Be sensitive to the need to separately interview parents and child, particularly if the child is an adolescent.

▪ Be sensitive to the need to consider who is responsible for health decisions in the family and for child care (see Chapter 1).

Information for Comprehensive History

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Date of History | Identifying Data |

| Include name of child and nickname (if any), names of parents and guardians, home telephone number, work numbers and hours when parents or guardians work, child’s date of birth, age (months, years), sex, race, language spoken, language understood. | Much of this information might already be on a child’s nameplate or chart. |

| Source of Referral, if Any | |

| Source of Information | |

| Include relationship of informant to child (child, parent, other) and judgment about reliability of information. If an interpreter has been used, note this as well. | Hesitations and vague or contradictory answers might raise concerns about reliability. |

| Chief Complaint | |

| Use broad opening statements, such as, “What concerns bring you here today?” Record parents’or child’s own words: “Running to the bathroom since Saturday.” | Note who identified the chief complaint. In some instances a schoolteacher or physician might have expressed the concern. Agreement between parents and another referral source is important to note. Adolescents and parents might differ regarding perception of complaint. |

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Present Illness | |

| Include a chronologic narrative of the chief complaint. The narrative answers questions related to where (location), what (quality, factors that aggravate or relieve symptoms), when (onset, duration, frequency), and how much (intensity, severity). The parent or child should also be asked about associated manifestations. Include significant negatives: “The parent denies that the child has experienced undue fatigue, bruising, or joint tenderness.” Ask what home and formal health care interventions have been tried to manage the concern and the effectiveness of these interventions. Inquire specifically about natural or homeopathic remedies as well. Use direct questions to focus on specific details, as necessary. |

Reasons for seeking care can provide valuable information about changes in the status of the child’s health concern. This information can aid in diagnosis and care planning

Parents might need assistance in sorting out details. Prior knowledge of diagnosis aids in planning specific questions; however, care must be taken to avoid premature closure or diminished openness to possibilities not presented by the diagnosis. In a primary care setting, the nurse often begins by addressing health maintenance or health-promoting issues.

Information about previously tried home and health care interventions provides important data about parent/child knowledge of interventions, self-care abilities, motivation, and cultural practices. Some folk remedies can be harmful. For example, two folk remedies from Mexico that are used to treat colic contain lead (azarcon and greta).

Clinical Alert

Persistent denial in the face of unexplained or vaguely defined injuries can signal child abuse. Denial might also indicate nonacceptance of a concern such as a developmental delay or behavior problem.

Insistent presentation of symptoms (especially by mother) in the absence of objective data might be suggestive of Munchausen syndrome by proxy.

|

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Medical History | |

| General State of Health | |

| Inquire about appetite, recent weight losses or gains, fatigue, stresses. | Do not include information that might have been elicited for chief complaint or present illness. |

| Birth History | |

| Include prenatal history (maternal health; infections; drugs taken, including prescription and illegal; tobacco and alcohol use; abnormal bleeding; weight gain; duration of pregnancy; attitudes toward pregnancy; birth; duration of labor; type of delivery; complications; birth weight; condition of infant at birth), and neonatal history (respiratory distress, cyanosis, jaundice, seizures, poor feeding, patterns of sleeping). | Birth history is especially important if the child is younger than 2 years or is experiencing developmental or neurologic problems. |

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Dietary History | |

| For infants, include type of feeding (bottle, breast, solid foods), frequency of feedings, quantity of feeds, responses to feeding, types of foods, specific problems with feeding (colic, regurgitation, lethargy). For children, include self-feeding abilities, likes and dislikes, appetite, and amounts of food taken. For adolescents, include usual eating patterns and daily caloric intake. |

Guidelines for a more complete nutritional history are supplied in Chapter 7.

Clinical Alert

Patterns and responses to feeding as an infant or as a child can be indicators of underlying concerns. For example, difficulty breastfeeding and/or slow eating as a preschooler and overwhelming preference for certain foods can be an indication of autism spectrum disorder. Skipping meals can be the strongest predictor of inadequate calcium intake in adolescents.

|

| Previous Illnesses, Operations, or Injuries | |

| Ask parents about other illnesses the child has had. Parents are likely to recall significant illnesses but might need guidance to talk about common childhood illnesses and details of these illnesses, such as tonsillitis and earaches. Include dates of hospitalizations, reasons for hospitalizations, and responses to illnesses. |

Knowing how a child reacted during past hospitalizations can help in planning interventions for a current hospitalization.

Negative or frightening experiences with illnesses or care need to be considered when approaching assessment and planning care.

Clinical Alert

If the child has experienced frequent accidents such as injuries or poisoning, this might indicate a need for teaching and guidance.

|

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Childhood Illnesses | |

| Include the common communicable diseases, such as measles, mumps, and chickenpox. Inquire about recent contact with persons with communicable diseases. | |

| Immunizations | |

| Include specific details about immunizations (dates, types) and untoward reactions. If a child has not been immunized, note the reason. Note desensitization procedures. |

Fainting, stable neurologic conditions, and mild illnesses are not contraindications for administration of immunizations.

Clinical Alert

Anaphylactic reactions such as hives, wheezing, difficulty breathing, or circulatory collapse (not fainting) after an immunization are contraindications to further doses.

An anaphylactic reaction to eating eggs is a contraindication for administration of influenza vaccine; an anaphylactic reaction to eating gelatin is a contraindication for administration of MMR.

Encephalopathy within 7 days of receiving DTP/DTaP is a contraindication for administering DTP/DTaP.

|

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Current Medications | |

| Include prescription and nonprescription drugs (ask specifically about use of vitamins, cold medications, herbs), dose, frequency, duration of use, time of last dose, and understanding of parents and/or child about the prescribed drugs. | Although herbs and vitamins are sometimes seen as natural substances, not as medications, parents and other caregivers need to consider these substances when asked about medications. Some herbs have powerful interactions with prescription medications (e.g., garlic can increase bleeding tendencies and therefore needs to be considered if medications are given that affect clotting times). |

| Allergies | |

| Include agent and reaction. | Knowing the reaction is useful because reactions might not be indicative of allergic manifestations. |

| Growth and Development | |

| Physical | |

| Include approximate height and weight at 1, 2, 5, and 10 years, and tooth eruption/loss. | A thorough history of growth and development is important in planning nursing interventions appropriate to the child’s level and in screening for developmental and neurologic problems. A social history can identify the need for anticipatory guidance. |

| Developmental History | |

| Include ages at which child rolled over, sat alone, crawled, walked, spoke first words, spoke first sentences, and dressed without help. | |

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

| Social and Psychosocial History | |

| Include toileting (age at which daytime and nighttime control were achieved or current level of control, enuresis, encopresis, selftoileting abilities, terminology used); sleep (amount, time to bed, ease in falling asleep, whether child/adolescent stays asleep, bedtime rituals, security objects, fears, nightmares, snoring, daytime sleepiness, falling asleep at school); speech (lisping, stuttering, delays, intelligibility); sexuality (relationships with members of opposite sex, inquisitiveness about sexual information and activity, type of information given child); schooling (school grade level, academic achievement, adjustment to school); habits (thumb sucking, nail biting, pica, head banging); discipline (methods used, child’s response to discipline); personality and temperament (congeniality, aggressiveness, temper tantrums, withdrawal, relationships with peers/family). |

Behaviors, such as those related to toilet training or sleep patterns and habits, vary with culture. Open discussion of sexual matters might be restricted in some cultures (e.g., Hispanics).

Clinical Alert

Behavior and temperament might provide important diagnostic and intervention information. Childrenwith hearing impairments and school-age children who experience recurrent abdominal pain are more likely to have difficult temperaments. Children with chronic cardiac disease are more intense, withdrawn, and more negative in mood than healthy children. Boys from violent home environments tend to bully, be argumentative, and have temper tantrums and short attention spans. Girls from violent homes tend to be anxious or depressed, to cling, and to be perfectionists.

Infants born to mothers on cocaine exhibit sleep problems.

|

| Children and adolescents should be asked if they ever feel sad or “down.” If yes, they should be asked if they have ever thought of killing themselves. | Daytime sleepiness, difficulties falling or staying asleep, and inadequate sleep might indicate sleep deprivation or an underlying sleep disorder, depression, sleep apnea, narcolepsy, or overuse of caffeinated drinks. If generalaspects of the health history indicate concern with psychosocial functioning, include the more detailed assessments provided in Chapter 24. |

| Information | Comment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Family History | |||

| Include the ages and health of immediate family members, familial diseases, presence and types of congenital anomalies, consanguinity of parents, occupations and education of parents, and family interactions, including who is primarily responsible for child care and for making decisions related to health care. |

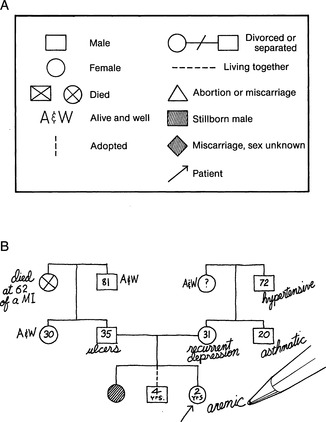

A genogram (Figure 2-1) is useful for showing the relationships, ages, health of family members, and who is in the household. (See Chapter 3 for a more detailed family assessment.) Needs of health care programs should be balanced with needs of families.

Parents identify their main needs as information about diagnosis, effect of diagnosis on development, information about treatment, and effect of condition on sexuality of child.

Clinical Alert

Be alert to symptoms of lead poisoning in children whose siblings or playmates are being treated for lead poisoning.

Parental age of less than 18 years at the time of child’s birth might be a risk factor for maltreatment.

|

||

| Information | Comment |

|---|---|

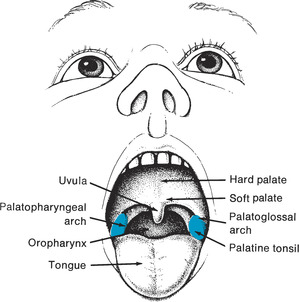

| Systems Review | |

|

1. General

2. Integument

3. Head and neck

4. Ears

5. Eyes

6. Face and nose

7. Thorax and lungs

8. Cardiovascular

9. Abdominal

10. Genitourinary/reproductive

11. Musculoskeletal

12. Neurologic

|

Questions appropriate for each system are included in other chapters in this book, under the heading “Preparation.” |