Diffuse Parenchymal Lung Diseases of Unknown Etiology

Approximately 65% of patients with diffuse parenchymal lung disease are victims of a process for which no etiologic agent has been identified, even though a specific name may be attached to the disease entity. Included in this category are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis associated with connective tissue disease, sarcoidosis, pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and a variety of other disorders. Many general aspects of these problems were discussed in Chapter 9. This chapter focuses on the specific diseases and their particular characteristics.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

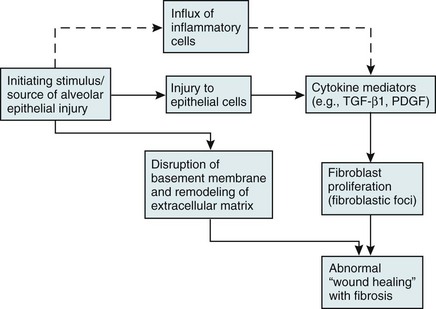

Over the past several years, a newer conceptual framework has emerged. According to the newer theory, alveolar inflammation does not play a critical role in the eventual development of fibrosis. Rather, fibrosis is believed to result directly from alveolar epithelial injury and is thought to be a manifestation of abnormal wound healing within the lung parenchyma. According to the newer paradigm, injury to alveolar epithelial cells (still from an unidentified source or agent) is the primary initiating event. Whereas injury to type I alveolar epithelial cells normally would be followed by a repair process that includes proliferation of type II cells and differentiation into type I cells, this repair process is impaired, at least in part because of disruption of the basement membrane, which normally is important for the reepithelialization process. At the same time, alveolar epithelial cells express a variety of profibrotic cytokines and growth factors, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1, which enhance fibroblast migration and proliferation. Fibroblastic foci develop at sites of alveolar injury and appear to be responsible for increased extracellular matrix deposition. This process is summarized in Figure 11-1.

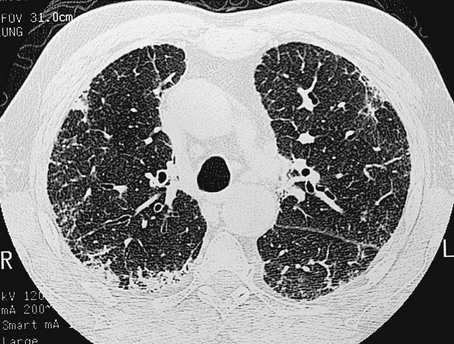

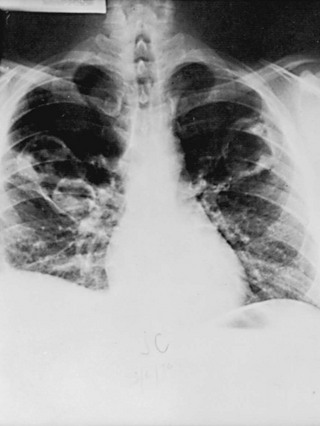

The chest radiograph shows an interstitial (reticular) pattern that is generally bilateral and relatively diffuse but typically is more prominent at the lung bases, particularly in the peripheral subpleural regions (see Fig. 3-6). Neither pleural effusions nor hilar enlargement is common on the radiograph. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) scanning often has a characteristic appearance, showing interstitial densities that are patchy, peripheral, subpleural, and associated with small cystic spaces (Fig. 11-2). The pattern of small cystic peripheral abnormalities on HRCT is termed honeycombing and indicates irreversible fibrosis. Many patients have serologic abnormalities, such as a positive test result for antinuclear antibodies, which are generally found in patients with autoimmune or connective tissue disease. However, in the absence of other suggestive clinical features, these abnormalities are thought to be nonspecific and not indicative of an underlying rheumatologic disease.

The diagnosis is definitively made by surgical lung biopsy, but only in the appropriate clinical setting when other etiologic factors for interstitial lung disease cannot be identified. Some patients are too frail for lung biopsy, and if HRCT scan shows the classic pattern of honeycombing, the diagnosis can be made with relative certainty without a lung biopsy. The histologic expression of IPF is in the form of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) (see Fig. 9-3), and patients who have a pathologic pattern more compatible with desquamative interstitial pneumonia or nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (see Other Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias; also see Chapter 9) should not be considered to have IPF. Granulomas should not be seen on an IPF biopsy specimen. If they are found, granulomas indicate the presence of another disorder.

Other Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

Several other disorders besides IPF fall under the category of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias and have often been confused with IPF. Although these disorders are uncommon, some are briefly described here, largely to clarify how their pathologic features differ from UIP and how their clinical features differ from IPF. They are also mentioned in Chapter 9 as part of the discussion on the pathology of the interstitial pneumonias.

Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia is a disorder characterized by connective tissue plugs in small airways accompanied by mononuclear cell infiltration of the surrounding pulmonary parenchyma. As noted in Chapter 9, the terms cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP) and bronchiolitis obliterans with organizing pneumonia (BOOP) have often been used interchangeably, but the term BOOP is best reserved for the pathologic picture rather than the clinical syndrome. Although the histologic picture of BOOP can be associated with connective tissue disease, toxic fume inhalation, or infection, the large majority of cases have no identifiable cause and are considered idiopathic. The term COP is most appropriate for patients who have “idiopathic BOOP”—that is, the histologic pattern of BOOP but no apparent cause for this pattern.

Like chronic eosinophilic pneumonia (see later), COP often has a subacute presentation (over weeks to months) with systemic (constitutional) as well as respiratory symptoms. The chest radiograph shows patchy infiltrates, generally with an alveolar rather than an interstitial pattern, often mimicking a community-acquired pneumonia (Fig. 11-3). Like chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, the response to corticosteroids is often dramatic and occurs over days to weeks. Therapy is usually prolonged for months to prevent relapse.

Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP) is a more acute or fulminant type of pulmonary parenchymal disease that begins with the clinical picture of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS; see Chapter 28) but without any of the usual inciting events associated with development of ARDS. Imaging studies of AIP typically show features of ARDS, including areas of ground-glass opacification and alveolar filling (as opposed to a purely interstitial pattern). The histologic pattern is that of diffuse alveolar damage, often showing some organization and fibrosis. Although mortality is high overall, a small percentage of patients do well, with clinical resolution of the disease and no long-term sequelae.

Pulmonary Parenchymal Involvement Complicating Connective Tissue Disease

Progressive systemic sclerosis, or scleroderma, is a disease with the most obvious manifestations located in the skin and small blood vessels. Other organ systems, including the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, kidneys, and heart, are involved relatively frequently. Of all the connective tissue diseases, scleroderma is the one in which pulmonary involvement tends to be most severe and most likely associated with significant scarring of the pulmonary parenchyma. Pulmonary fibrosis complicating scleroderma appears to be strongly associated with the presence of a particular serologic marker, an autoantibody to topoisomerase I (antitopoisomerase I, also called Scl70). Another potential pulmonary manifestation of scleroderma is disease of the small pulmonary blood vessels, producing pulmonary arterial hypertension, which is discussed in Chapter 14. This involvement appears to be independent of the fibrotic process affecting the alveolar walls.

Sarcoidosis

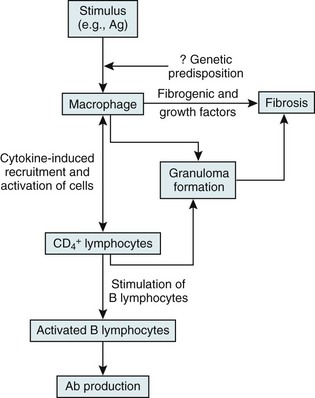

On the other hand, substantial information is available about cells and mediators that appear to be important in the inflammatory and granulomatous tissue reaction in sarcoidosis (Fig. 11-4). The critical cells are macrophages and T lymphocytes. The presumption is that processing of the responsible antigen by alveolar macrophages results in recruitment of helper T lymphocytes (CD4+ cells) with a TH1 profile. A host of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as interleukin (IL)-2, interferon (IFN)-γ, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-12, appear to be important in recruiting and activating inflammatory cells, perpetuating the inflammatory response, and inducing the formation of granulomas. Profibrotic cytokines, such as TGF-β, PDGF, and insulinlike growth factor (IGF)-1, subsequently may result in fibrosis as a complication of the initial inflammatory reaction.

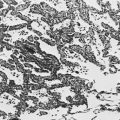

The characteristic histopathologic feature of sarcoidosis is the noncaseating granuloma (see Fig. 9-2). These typically well-formed granulomas show a collection of tissue macrophages (also called epithelioid histiocytes), multinucleated giant cells, and T lymphocytes, particularly toward the periphery or at the rim of the granuloma. The discrete accumulation of tissue macrophages comprising the granuloma does not show evidence of frank necrosis or caseation, as would appear in disorders like tuberculosis and histoplasmosis. In addition to granulomas in the lung parenchyma or intrathoracic lymph nodes, an alveolitis often occurs. The alveolitis is composed of mononuclear cells, including macrophages and lymphocytes, with the latter presumed to be of particular importance in the pathogenesis of disease.

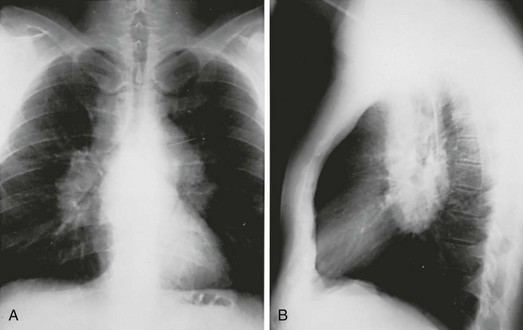

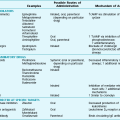

The chest radiograph in sarcoidosis generally shows one of the following patterns: (1) enlargement of lymph nodes, most commonly bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy with or without paratracheal node enlargement (Fig. 11-5); (2) parenchymal lung disease (in the form of interstitial disease, nodules, or alveolar infiltrates); or (3) both adenopathy and parenchymal disease (Fig. 11-6). HRCT scanning, although not generally necessary, is more sensitive than plain chest radiography in detecting parenchymal lung disease. It may show a particularly characteristic pattern of small nodules preferentially distributed along bronchovascular bundles (Fig. 11-7). In addition, HRCT often demonstrates mediastinal lymphadenopathy that cannot be seen on plain chest radiography.

Miscellaneous Disorders Involving the Pulmonary Parenchyma

Wegener Granulomatosis

A group of disorders termed the granulomatous vasculitides may affect the alveolar wall as part of a more generalized disease. The most well known of these disorders is Wegener granulomatosis, a disease characterized primarily but not exclusively by involvement of the upper respiratory tract, lungs, and kidneys. The pathologic process in the lungs and upper respiratory tract consists of a necrotizing small-vessel granulomatous vasculitis, whereas a focal glomerulonephritis is present in the kidney. On chest radiograph, patients commonly have one or several nodules (often large) or infiltrates, often with associated cavitation of the lesion(s) (Fig. 11-8). Unlike most of the other disorders of the pulmonary parenchyma discussed in Chapter 10 and this chapter, diffuse interstitial lung disease is not the characteristic radiographic finding in this entity.

Chronic Eosinophilic Pneumonia

Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia is a disorder in which the pulmonary interstitium and alveolar spaces are infiltrated primarily by eosinophils and, to a lesser extent, by macrophages. The clinical presentation typically occurs over weeks to months, with systemic symptoms such as fever and weight loss accompanying dyspnea and a nonproductive cough. The clues suggesting this diagnosis are often found on the chest radiograph and the routine white blood cell differential count. The radiograph frequently shows pulmonary infiltrates with a peripheral distribution and a pattern more suggestive of alveolar filling than interstitial disease (Fig. 11-9). Because the typical radiographic pattern of pulmonary edema with congestive heart failure has central pulmonary infiltrates with sparing of the lung periphery, the prominent peripheral pattern often seen in chronic eosinophilic pneumonia has been described as the “photographic negative of pulmonary edema.” The majority of patients also have increased numbers of eosinophils in peripheral blood, although this finding is not uniformly present and therefore is not critical for the diagnosis. However, bronchoalveolar lavage typically shows a high percentage of eosinophils, reflecting the pathologic process within the pulmonary parenchyma.

Armanios, MY, Chen, JJ, Cogan, JD, et al. Telomerase mutations in families with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1317–1326.

ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Fell, CD, Martinez, FJ, Liu, LX, et al. Clinical predictors of a diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:832–837. 15

Gansner, JM, Rosas, IO, Ebert, BL. Pulmonary fibrosis, bone marrow failure, and telomerase mutation. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1551–1553.

Garcia, CK. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: update on genetic discoveries. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2011;8:158–162.

Günther, A, Korfei, M, Mahavadi, P. Unravelling the progressive pathophysiology of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2012;21:152–160.

Guenther, A, European IPF Network. The European IPF Network: towards better care for a dreadful disease. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:747–748.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network. Prednisone, azathioprine, and N-acetylcysteine for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1968–1977.

Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis Clinical Research Network Investigators. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:636–643.

King, TE, Jr., Pardo, A, Selman, M. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Lancet. 2011;378:1949–1961.

Lawson, WE, Loyd, JE, Degryse, AL. Genetics in pulmonary fibrosis—familial cases provide clues to the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:439–443.

Ley, B, Collard, HR, King, TE, Jr. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–440.

Maher, TM, Wells, AV, Laurent, GJ. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: multiple causes and multiple mechanisms? Eur Respir J. 2007;30:835–839.

Nathan, SD, Shlobin, OA, Weir, N, et al. Long-term course and prognosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in the new millennium. Chest. 2011;140:221–229.

Selman, M, Pardo, A. Role of epithelial cells in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: from innocent targets to serial killers. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:364–372.

Strieter, RM, Mehrad, B. New mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2009;136:1364–1370.

Tanjore, H, Blackwell, TS, Lawson, WE. Emerging evidence for endoplasmic reticulum stress in the pathogenesis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2012;302:L721–L729.

Vancheri, C, Failla, M, Crimi, N, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disease with similarities and links to cancer biology. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:496–504.

Zoz, DF, Lawson, WE, Blackwell, TS. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a disorder of epithelial cell dysfunction. Am J Med Sci. 2011;341:435–438.

Other Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias

American Thoracic Society and European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary consensus classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:277–304.

Bouros, D, Nicholson, AC, Polychronopoulos, V, et al. Acute interstitial pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2000;15:412–418.

Caminati, A, Harari, S. Smoking-related interstitial pneumonias and pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:299–306.

Collard, HR, King, TE, Jr. Demystifying idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:17–29.

Cordier, JF. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:727–738.

Epler, GR. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:158–164.

Ferguson, EC, Berkowitz, EA. Lung CT: Part 2, The interstitial pneumonias—clinical, histologic, and CT manifestations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:W464–476.

Kinder, BW, Collard, HR, Koth, L, et al. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: lung manifestation of undifferentiated connective tissue disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:691–697.

Visscher, DW, Myers, JL. Histologic spectrum of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:322–329.

Young, DA, Cherniack, RM, King, TE, et al. Acute interstitial pneumonitis. Case series and review of the literature. Medicine. 2000;79:369–378.

Pulmonary Parenchymal Involvement Complicating Connective Tissue Disease

Connors, GR, Christopher-Stine, L, Oddis, CV, et al. Interstitial lung disease associated with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: what progress has been made in the past 35 years? Chest. 2010;138:1464–1474.

Gochuico, BR. Potential pathogenesis and clinical aspects of pulmonary fibrosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:83–88.

Grutters, JC, Wells, AU, Wuyts, W, et al. Evaluation and treatment of interstitial lung involvement in connective tissue diseases: a clinical update. Eur Respir Mon. 2006;34:27–49.

Keane, MP, Lynch, JP. Pleuropulmonary manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Thorax. 2000;55:159–166.

Kim, EJ, Collard, HR, King, TE, Jr. Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern. Chest. 2009;136:1397–1405.

Strange, C, Highland, KB. Interstitial lung disease in the patient who has connective tissue disease. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:549–559.

Swigris, JJ, Fischer, A, Gilles, J, et al. Pulmonary and thrombotic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus. Chest. 2008;133:271–280.

Westhovens, R, De Keyser, F, van den Hoogen, FHJ, et al. The clinical spectrum and pathogenesis of pulmonary manifestations in connective tissue diseases. Eur Respir Mon. 2006;34:1–26.

Drent, M, Costabel, U. Sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Mon. 2005;10:1–341.

Iannuzzi, MC, Rybicki, BA, Teirstein, AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165.

Lodha, S, Sanchez, M, Prystowsky, S. Sarcoidosis of the skin: a review for the pulmonologist. Chest. 2009;136:583–596.

Lynch, JP, 3rd., Ma, YL, Koss, MN, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:53–74.

Mandel, J, Weinberger, SE. Clinical insights and basic science correlates in sarcoidosis. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:99–107.

Morgenthau, AS, Iannuzzi, MC. Recent advances in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2011;139:174–182.

O’Regan, A, Berman, JS, Cotton, D, et al. Sarcoidosis. Ann Intern Med.. 156(9), 2012. ITC5-1-ITC5-16

Paramothayan, S, Jones, PW. Corticosteroid therapy in pulmonary sarcoidosis. A systematic review. JAMA. 2002;287:1301–1307.

Weinberger, SE. Clinical crossroads: a 47-year-old woman with sarcoidosis. JAMA. 2006;296:2133–2140.

Zissel, G, Prasse, A, Muller-Quernheim, J. Sarcoidosis—immunopathogenetic concepts. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;28:3–14.

Miscellaneous Disorders Involving the Pulmonary Parenchyma

Ball, JA, Young, KR. Pulmonary manifestations of Goodpasture’s syndrome. Antiglomerular basement membrane disease and related disorders. Clin Chest Med. 1998;19:777–791.

Carsillo, T, Astrinidis, A, Henske, EP. Mutations in the tuberous sclerosis complex gene TSC2 are a cause of sporadic pulmonary lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6085–6090.

Collard, HR, Schwarz, MI. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25:583–592.

Cottin, V, Cordier, JF. Eosinophilic pneumonias. Allergy. 2005;60:841–857.

Doershuk, CM. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis—is host defense awry? N Engl J Med. 2007;356:547–549.

Frankel, SK, Cosgrove, GP, Fischer, A, et al. Update in the diagnosis and management of pulmonary vasculitis. Chest. 2006;129:452–465.

Frankel, SK, Schwarz, MI. The pulmonary vasculitides. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:216–224.

Greenhill, SR, Kotton, DN. Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis: a bench-to-bedside story of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor dysfunction. Chest. 2009;136:571–577.

Henske, EP, McCormack, FX. Lymphangioleiomyomatosis – a wolf in sheep’s clothing. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3807–3816.

Juvet, SC, McCormack, FX, Kwiatkowski, DJ, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of lymphangioleiomyomatosis: lessons learned from orphans. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:398–408.

Lara, AR, Schwarz, MI. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Chest. 2010;137:1164–1171.

Lin, FC, Chang, GD, Chern, MS, et al. Clinical significance of anti-GM-CSF antibodies in idiopathic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Thorax. 2006;61:528–534.

Marchand, E, Cordier, JF. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;27:134–141.

National Institutes of Health Rare Lung Diseases Consortium; MILES Trial Group. Efficacy and safety of sirolimus in lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1595–1606.

Review Panel of the ERS LAM Task Force. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the diagnosis and management of lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:14–26.

Sakagami, T, Uchida, K, Suzuki, T, et al. Human GM-CSF autoantibodies and reproduction of pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2679–2681.

Strizheva, GD, Carsillo, T, Kruger, WD, et al. The spectrum of mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 in women with tuberous sclerosis and lymphangioleiomyomatosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:253–258.

Suri, HS, Yi, ES, Nowakowski, GS, et al. Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2012;7:16.

Uchida, K, Beck, DC, Yamamoto, T, et al. GM-CSF autoantibodies and neutrophil dysfunction in pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:567–579.

Vassallo, R, Schroeder, DR, Decker, PA, et al. Clinical outcomes of pulmonary Langerhans-cell histiocytosis in adults. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:484–490.

Venkateshiah, SB, Yan, TD, Bonfield, TL, et al. An open-label trial of granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor therapy for moderate symptomatic pulmonary alveolar proteinosis. Chest. 2006;130:227–237.