Chapter 16 Differential Diagnosis of Restless Legs Syndrome

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) continues to elude recognition and diagnosis despite a lucid description of the entity by Ekbom1 in the middle of the last century. In the latter part of the 19th century and the early part of the 20th century, RLS was believed to be a psychosomatic condition. This myth was somewhat dispelled following Ekbom’s description using the term “restless legs.” Even today, many physicians do not recognize the condition and mistake it for other superficially similar conditions. Another reason for mistaken diagnosis is that there is not a single diagnostic test for RLS. Diagnosis is entirely clinical and based on the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) criteria2,3 (essential, supportive, and associated) as outlined in Chapter 15. It is, therefore, incumbent on the family physicians, sleep and movement disorder specialists, neurologists, psychiatrists, internists including pulmonologists and pediatricians, to be conversant with those conditions that mimic RLS. We do not find a definite cause for RLS in most of the patients (primary RLS), but some cases of RLS are associated with other disorders or intake of certain medications. Patients with the latter cases are said to have secondary or comorbid RLS; however, whether these patients were predisposed (genetically or otherwise) to develop this condition and simply had the condition triggered by comorbidities or medications remains undetermined.

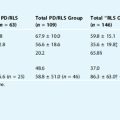

Conditions That Mimic Restless Legs Syndrome

The conditions discussed in this section often mimic the clinical features of RLS, making it difficult to differentiate them from true RLS. These conditions do not cause RLS, but it is important for every physician dealing with RLS to be familiar with the essential features of these mimics (Box 16-1). There are two major classes of disorders that can be confused with RLS—those that involve abnormal restlessness, such as akathisia, and those that are associated with pain or discomfort in the legs.

BOX 16-1 Disorders and Conditions That Can Be Confused With Restless Legs Syndrome

Akathisia

The most important condition that mimics RLS and sometimes the most difficult to differentiate from RLS, particularly the most severe forms of RLS, is akathisia. Since Sigwald and colleagues4 in 1947 described phenothiazine-induced restlessness in a patient with Parkinson’s disease (PD), neuroleptic-induced akathisia (NIA) has emerged as an important side effect of neuroleptics in the second half of the 20th century. It is, however, interesting to note that the term akathisia was used in 1901 by Ludwig Haskovec,5 the Czech neuropsychiatrist, long before the advent of neuroleptics, and he thought that akathisia was a manifestation of hysteria. The term akathisia is derived from the Greek word meaning “inability to sit.” The next milestone in the history of akathisia was the description of motor restlessness in PD unrelated to medications by Bing6 and Sicard7 in 1923 (Bing-Sicard akathisia). In contemporary writings, NIA remains the most familiar and acceptable term. This can be acute, tardive, chronic, and related to withdrawal of neuroleptics. Clinically, there are two essential components: subjective (feeling of inner restlessness) and objective (observed motor restlessness). In 1973, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) task force defined akathisia as “a subjective desire to be in constant motion” associated with “an inability to sit or stand still” and “a drive to pace up and down.”8 The inner feeling of restlessness, jitteriness, or fidgetiness results in forced walking (tasikinesia) and other motor manifestations. Patients have difficulty sitting still; they keep moving, cross and uncross their legs, sway and rock their whole body, march in place, and constantly shift body positions while sitting. Although motor restlessness is prominent in the legs, the whole body, including trunk and arms, manifests these restless movements, which could be synchronous, asynchronous symmetrical, asymmetrical, rhythmic, or arrhythmic, resembling choreiform rather than the voluntary and myoclonic movements seen in patients with RLS. To some extent, these movements can be suppressed temporarily, but over a more prolonged period, they are uncontrollable and involuntary. These movements are present throughout the day and may become worse in the evening, but there is no circadian pattern, unlike that noted in RLS. Furthermore, the near constant movements do not relieve the intense urge to move. The following clinical features differentiate akathisia from RLS: movements of the whole body; inability to stand still; failure to get relief from these movements; lack of a circadian pattern of not being limited to the evening; presence of these restless movements not only during inactivity but also while standing and walking as if the whole body is in constant motion; and absence of uncomfortable, disagreeable sensations in the legs (which may be present in some patients with akathisia). Furthermore, periodic limb movements, which may be present with RLS, are uncommon and not prominent features of akathisia. There is generally no positive family history for akathisia, which is another differentiating feature from RLS. History of drug exposure (mostly neuroleptics, rarely selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] and other antipsychotic drugs) before the period of restlessness is an essential criterion for diagnosing NIA. Physical examination (while sitting, standing, or lying down) reveals the distinctive motor restlessness and sometimes drug-induced extrapyramidial manifestations in akathisia in contrast to normal examination in idiopathic or primary RLS. In secondary RLS, however, physical findings related to the primary conditions that are associated with RLS may be present. Polysomnographically,9 there are no distinctive features, and in rare occasions, there may be evidence of mild sleep disturbance and periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) in akathisia in contrast to severe sleep disturbance and presence of PLMS in at least 80% of patients with RLS. In advanced stages of RLS, some patients may complain of generalized restlessness involving the trunk and arms, and lack of significant relief by their movement, making it difficult to differentiate from akathisia; thus, advanced stages of RLS may closely resemble classic akathisia with restlessness during both the day and night and little relief despite continuous motion. In these patients, however, history will include that these patients had symptoms characteristic of RLS rather than akathisia at the onset of the illness.

Sometimes neuroleptic-induced akathisia manifests as focal akathisia (monoakathisia)10,11 characterized by rhythmic swaying of the leg while sitting and flexing the knee intermittently while standing up. Carrazana and colleagues12 described contralateral akathisia (hemi-akathisia) following a subthalamic abscess. Occasionally, patients with RLS present with a unilateral leg manifestation resembling unilateral or focal akathisia, but other distinctive features described earlier and in Chapter 15 should clearly differentiate RLS from focal akathisia. Another feature to remember is that mild cases of akathisia may demonstrate variability with only intermittent presence similar to that noticed sometimes with RLS, particularly in the early stage of the illness.

Syndrome of Painful Legs and Moving Toes

This condition is characterized by spontaneous, involuntary, and purposeless movements of the toes consisting of flexion, extension, abduction, and adduction accompanied by deep aching or pulling pain in the feet or the lower part of the legs. Since its original description by Spillane and colleagues13 in 1971, both painful and painless legs and moving toes syndrome as unilateral or bilateral presentations have been described in scattered case reports attesting to the heterogeneity of this entity. Movement of the toes does not relieve the pain, in contrast to that noted in RLS patients. The movements are not prominent during sleep and are not particularly intense in the evening. Pathophysiology of the condition remains uncertain. Most cases result from a peripheral cause, such as lumbosacral radiculapathy, or minor local trauma can bring this about, but some are caused by central nervous system lesions. Very limited study of physiologic analysis showed two distinct electromyelographic (EMG) burst patterns14: synchronous activities in the agonist and antagonist muscles in the peripheral type and alternating EMG bursts in the agonist and antagonist muscles in the central type. Polysomnographic study has rarely been performed. In our own physiologic observations including polysomnographic study,15 we noted a mixture of dystonic, myoclonic, synchronous, asynchronous, and triphasic EMG bursts suggesting complex pathophysiology, which may involve both peripheral afferent and supraspinal efferent control.

Muscular Pain—Fasciculation Syndrome

This is a rare condition characterized by widespread fasciculation that is often made worse by exercise, consumption of coffee or anxiety accompanying the occasional cramps at night, and dull, aching pain in the limbs.16 Sometimes the patient may have restlessness of the legs, but the symptoms in this condition do not necessarily improve on walking or with exercise, thus clearly differentiating them from the essential clinical features of RLS.

Myokymia

This condition is characterized by a slow vermicular spontaneous contraction of broad strips of muscle. This may or may not disappear during sleep depending on whether the lesion is in the peripheral or the central nervous system. Myokymia may also occur in apparently normal individuals after fatigue. Myokymia may occasionally cause abnormal movements of the toes and may be associated with features resembling restlessness of the legs. Masland17 first noted an association between myokymia and RLS. The characteristic features of myokymia, generally localized nature of the symptoms, and the lack of clear relationship between rest, sleep, or time of the day should clearly differentiate myokymia from RLS.

Causalgia-Dystonia Syndrome

This condition is characterized by dystonic muscle spasms in the affected part; usually, the legs are affected in most of the cases, at least initially, but the arms may also be affected.18 Generally, dystonia and causalgia are noted simultaneously. The condition is often triggered by minor trauma and has been noted more commonly in women than in men. The causalgic symptoms consist of burning pain, allodynia and hyperpathia accompanied by vasomotor, pseudomotor, and trophic skin changes. These spasms produce a fixed dystonic posture. There is no positive family history and contractures are uncommon. There is no circadian feature. All these clinical features are easy to differentiate from RLS. The nature of this condition at present is unknown, but it has been suggested that it may be of psychogenic origin.

Painful Muscle Cramps Including Nocturnal Leg Cramps

Muscle cramps may occur in central or peripheral neurologic disorders. Symptoms may occur at rest or be induced by exercise or ischemia. There are many causes of cramps at rest or on contraction, including motor neuron disease, tetany, hyponatremia, uremia, hypocalcemia, hypomagnesemia, chronic polyneuropathy, and muscle diseases such as myoglobinuria, myophosphorylase, phosphofructokinase and carnitine-palmitoyl transferase deficiency, myotonia, stiff-man syndrome, myokymia, tetanus, and neuromyotonia. A special variety of muscle cramps known as nocturnal leg cramps19 is characterized by painful spasms of the muscles, usually in the calf but occasionally in the foot, beginning during sleep at night. The cramps may cause arousal or awakening from sleep. These cramps can be relieved by local massage or movement of the affected limb, thus superficially resembling RLS. The symptoms in these patients are not necessarily present during inactivity or in the evening and not accompanied by an urge to move the limbs. These nocturnal leg cramps are often relieved by dorsiflexion of the foot. Polysomnographically, there are bursts of EMG activities in the gastrocnemius muscles seen at random. The characteristic clinical features, EMG, and other appropriate laboratory tests are helpful in arriving at the correct diagnosis. After excluding all the causes, there remains a condition known as benign idiopathic cramp syndrome without any underlying etiology. It is also the case that almost all adults will experience one or more cramps at some point in their lives. Although cramps can satisfy the four diagnostic features of RLS, individuals with cramps usually describe them as having a distinct painful and localized nature or, if less frequent and severe, merely consider them a normal phenomenon and do not seek medical intervention for them.

Hypnic Jerks

Hypnic jerks, or “sleep starts,” consist of brief muscle jerks involving the legs or arms or whole body occurring at sleep onset.20 Sometimes, these are accompanied by a sense of falling or other sensory phenomena and rarely the patient may have pure sensory “sleep starts.”21 These are physiologic and have no pathologic significance. Sometimes, these occur repetitively at sleep onset, causing intensified hypnic jerks and sleep-onset insomnia.22 These may be triggered by stress, fatigue, or sleep deprivation. These features are completely different from the essential criteria of RLS.

Essential Myoclonus

Occasionally, essential myoclonus may superficially resemble RLS, causing diagnostic confusion. Essential myoclonus usually appears in the first or second decade of life and can be familial or nonfamilial. The course is benign without any progression, and neurologic examination is normal except for the presence of myoclonus. The movements consist of sudden shock-like muscle jerks that may be seen synchronously or asynchronously, symmetrically or asymmetrically, diffusely or focally, and rhythmically or arrhythmically.23 These are often triggered by sudden noise. EMG burst duration is much briefer than that noted in RLS or PLMS. These movements are increased by emotional stress but absent during sleep. There is no urge to move the limbs and no predilection for occurrence in the evening or during inactivity. Sometimes true myoclonic movements during rest and inactivity may be seen in patients with RLS. The clinical and EMG characteristics, however, differentiate the condition of essential myoclonus easily from RLS.

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

Periodic limb movements in sleep (PLMS) is a polysomnographic finding characterized by periodically recurring limb movements during nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep.24 Most commonly, the patients dorsiflex the toes and ankles and flex the knees and hips, periodically every 5 to 90 seconds (most commonly, 20 to 40 seconds).25 Occasionally, PLMS are noted in the upper limbs.26 The movements have a duration of 0.5 to 10 seconds and must be part of at least four consecutive movements (see Chapter 17). Limb movements may be accompanied by partial arousals causing sleep fragmentation. The PLMS index (number of PLMS per hour of sleep) of 5 is considered normal.

PLMS is seen most commonly in RLS (at least in 80% of patients) but is also seen frequently in patients with REM behavior disorder (RBD) (70%) and narcolepsy (50% to 55%).27,28 PLMS may also be seen in a large number of other medical, neurologic, and sleep disorders and in association with medications (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants, SSRIs, L-dopa, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Whether PLMS occurs as a primary condition, not associated with RLS, RBD, or narcolepsy, causing repeated awakenings and sleep fragmentations as described in the International Classification of Sleep Disorder under the heading of periodic limb movement disorders (PLMD)25 remains controversial. There is a growing body of evidence that PLMS may not have a specific clinical significance and is simply a polysomnographic observation seen in a variety of sleep disorders associated with dopaminergic impairment.29,30 Whether PLMS leads to nighttime sleep disturbance causing daytime somnolence remains uncertain, and suppression of PLMS by clonazepine treatment may not relieve daytime somnolence. The other problem is differentiating PLMS from respiratory-related PLM seen in patients with obstructive sleep apnea or other cyclic respiratory abnormalities accompanied by recurrent episodes of respiratory compromise followed by resumed normal respiration with PLM.30 PLMS related to respiratory disturbances may be missed unless sensitive sensors, such as nasal pressure cannula recordings, are performed to detect these movements. PLMS should not be mistaken for RLS, as PLMS are supportive evidence of RLS.

“Growing Pains” and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Many children with a diagnosis of “growing pains” may actually be having early symptoms of RLS. Because of the general misperception that RLS is an adult disease, these symptoms are often misdiagnosed in children. Several cases of childhood onset of RLS have been described.31,32 A subgroup of those patients with “growing pains” have symptoms of ADHD.33 Some of the ADHD patients present with RLS symptoms, like leg paresthesia, and in fact could be a subgroup of childhood-onset RLS. These children have exhibited nocturnal motor activity, and there is an increased PLMS index in many of these patients. According to Picchietti and Walters,31 these patients may represent phenocopy in which RLS superficially mimics or causes ADHD, but there may be some common pathophysiology between RLS and ADHD. Although growing pains may be different from RLS in having truly painful symptoms with relief by massage rather than motion, some growing pains appear to be a form of RLS or a precursor to adult RLS.33

Orthostatic Tremor

Orthostatic tremor (OT) is a characteristic clinical syndrome involving tremulousness of the legs that develops seconds to minutes after standing up. This is sometimes described as “shaky legs syndrome.” The shakiness or tremor improves on walking. Because of superficial resemblance to restlessness or shakiness and improvement on walking, this is sometimes mistaken for RLS. However, the entity lacks the essential diagnostic criteria of RLS as described in Chapter 15. Furthermore, it is present only on standing and not when the patient is lying down, and there is no circadian pattern. Special electrodiagnostic recording using multiple muscles (polymyographic recording of the upper and lower limbs) shows a characteristic tremor at the rate of 15 to 17 Hz predominantly in the legs but sometimes noticed synchronously in the upper limbs. Heilman34 coined the term “orthostatic tremor,” and since then there have been many related reports in the literature.35 One controversy is whether OT is a variant of essential tremor,36 but the characteristic clinical features and the electrophysiologic features differentiate OT from essential tremor.

Orthostatic Hypotensive Restlessness

Some patients with orthostatic or postural hypotension may complain of feelings of restlessness limited to the legs and noted only when the patient either stands up or sits up from a lying position.37 These features are totally different from the essential diagnostic criteria of RLS. Furthermore, the patient often complains of dizziness or faint feelings in the upright posture along with restlessness of the legs. Recording of blood pressure will document significant orthostatic fall of blood pressure from the supine position. In contrast to RLS patients, these individuals’ symptoms will improve when they lie down.

Conditions Associated With Restless Legs Syndrome (Symptomatic or Comorbid Restless Legs Syndrome)

This category lists conditions that may be associated with RLS. These are traditionally classified in the secondary or symptomatic class of RLS (Box 16-2). The term “secondary” implies causality; however, whether these conditions actually are responsible for RLS or simply aggravate or trigger RLS in patients already predisposed (probably genetically) to this condition remains to be determined. Hence, the term “secondary RLS” might be replaced by “comorbid RLS.” It is important to have a basic knowledge about the comorbid conditions so that corrective actions to alleviate or eliminate the condition associated with RLS can be introduced and RLS-specific drugs can be used if needed. These disorders are discussed in Chapters 21 through 28.

Approach to Conditions Mimicking Restless Legs Syndrome or Associated With Restless Legs Syndrome

In the differential diagnosis between primary RLS and those conditions mimicking RLS or associated with RLS, it is important to look for clues, including subtle signs based on history and physical findings that point to the correct diagnosis. History should include a detailed description of the present complaint including duration and nature of the sensorimotor complaints and past, family, psychiatric, and drug histories. For the diagnosis of RLS (primary or comorbid), four IRLSSG essential criteria must be met with or without the supportive and associated features (see Chapter 15). For the diagnosis of mimics and conditions associated with RLS, salient features as summarized earlier or discussed in the respective chapters (see Chapters 21 through 28) should help in arriving at the correct diagnosis. In addition to history and physical examination, laboratory tests, which should be subservient to clinical information, may be needed to confirm the diagnoses of other conditions superficially resembling or associated with RLS. These tests may include overnight polysomnography, actigraphy, electromyography and nerve conduction studies, hematologic and biochemical tests in blood samples, urinalysis, drug screening, and neuroimaging tests (Box 16-3).

1. Ekbom KA. Restless legs: A clinical study. Acta Med Scand Suppl. 1945;158:1-123.

2. Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

3. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

4. Sigwald J., Grossiord A, Duriel P, et al. Le traitment de la maladie Parkinson et des manifestations extrapyramidalles par le diethylaminoethyl n- thiophenylamine (2987 RP): Resultants d’une anee d’application. Rev Neurol. 1947;79:683-687.

5. Haskovec L. L’akathisie. Rev Neurol. 1901;9:1107-1109.

6. Bing R. Uber einige bemerkenswerte beglieterscheinwigen der ‘extrapyramidalen rigidat’ (on some outstanding side effects of extrapyramidal rigidity) (Akathisie-mikrographie—kinesia paradoxa). Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1923;4:167-171.

7. Sicard JA. Akathisie and tasikinesie. Presse Med. 1923;31:265-266.

8. American College of Neuropsychopharmacology—Food and Drug Administration Task Force. Neurological syndromes associated with antipsychotic drug use. N Engl J Med. 1973;289:20-23.

9. Walters AS, Hening W, Rubinstein M, Chokroverty S. A clinical and polysomnographic comparison of neuroleptic-induced akathisia and the idiopathic restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1991;14:339-345.

10. Yamashita H, Horiguchi J, Mizuno S, et al. A case of neuroleptic-induced unilateral akathisia with periodic limb movements in the opposite side during sleep. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1999;53:291-293.

11. Hermesh H, Munitz H. Unilateral neuroleptic-induced akathisia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1990;13:253-258.

12. Carrazana E, Rossitch EJr, Martinez J. Unilateral “akathisia” in a patient with AIDS and a toxoplasmosis subthalmamic abscess. Neurology. 1989;39:449-450.

13. Spillane JD, Nathan PW, Kelly RE, Marsden ED. Painful legs and moving toes. Brain. 1971;94:541-556.

14. Schoenen J, Gonce M, Delwaide PJ. Painful legs and moving toes: A syndrome with different physiopathologic mechanisms. Neurology. 1984;34:1108-1112.

15. Reddy R, Siddiqui F, Dinar AH, et al. A polymyographic and polysomnographic analysis of painful and painless legs moving toes syndrome [abstract]. Mov Disord. 2005;20(supp. 10):S64.

16. Hudson AJ, Brown WF, Gilbert JJ. The muscular pain-fasciculation syndrome. Neurology. 1978;28:1105-1109.

17. Masland RL. Myokymia: A cause of restless legs. JAMA. 1947;134:1298.

18. Bhatia KP, Bhatt MH, Marsden CD. The causalgia-dystonia syndrome. Brain. 1993;116:843-851.

19. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders. In Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 2, Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005:187-188.

20. Oswald I. Sudden bodily jerks on falling asleep. Brain. 1959;82:92-103.

21. Sander H, Geisse H, Quinto C, et al. Sensory sleep starts. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;64:690.

22. Broughton R. Pathological fragmentary myoclonus, intensified sleep starts and hypnagogic foot tremor: Three unusual sleep related disorders. In: Koella WP, editor. Sleep. New York: Fischer-Verlag; 1988:240-243.

23. Chokroverty S, Manocha MK, Duvoisin RC. A physiologic and pharmacologic study in anticholinergic-responsive essential myoclonus. Neurology. 1987;37:608-615.

24. Coleman RM, Pollak CP, Weitzman ED. Periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus): Relations to sleep disorders. Ann Neurol. 1980;18:416-421.

25. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders. In: Diagnostic and Coding Manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005:182-186.

26. Chabli A, Michaud M, Montplaisir J. Periodic arm movements in patients with the restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;44:133-138.

27. Hening W, Allen R, Walters A, Chokroverty S. Motor functions and dysfunctions of sleep. In: Chokroverty S, editor. Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects. Boston: Butterworth; 1999:441-507.

28. Wetter TC, Pollmacher T. Restless legs and periodic leg movements in sleep syndromes. J Neurol. 1997;244:S37-S45.

29. Mahowald MW. Hope for the PLMs quagmire? Sleep Med. 2002;3:463-464.

30. Exar EN, Collop NA. The association of upper airway resistance with periodic limb movements. Sleep. 2001;24:188-192.

31. Picchietti DL, Walters AS. Moderate to severe periodic limb movement disorder in childhood and adolescence. Sleep. 1999;22:297-300.

32. Picchietti DL, Underwood DJ, Farris WA, et al. Further studies on periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mov Disord. 1999;14:1000-1007.

33. Rajaram SS, Walters AS, England SJ, et al. Some children with growing pains may actually have restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 2004;27:767-773.

34. Heilman KM. Orthostatic tremor. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:880-881.

35. Sander HW, Masdeu JC, Tavoulaeas G, et al. Orthostatic tremor: An electrophysiological analysis. Mov Disord. 1998;13:735-738.

36. Papa S, Gershanik OS. Orthostatic tremor: An essential tremor variant. Mov Disord. 1988;3:97-108.

37. Cheshire WPJr. Hypotensive akathisia: Autonomic failure associated with leg fidgeting while sitting. Neurology. 2000;55:1923-1926.

38. Shaughnessy P, Lee J, O’Keeffe ST. Restless legs syndrome in patients with hereditary hemochromatosis. Neurology. 2005;64:2158.