Chapter 1 Diagnosis of Neurological Disease

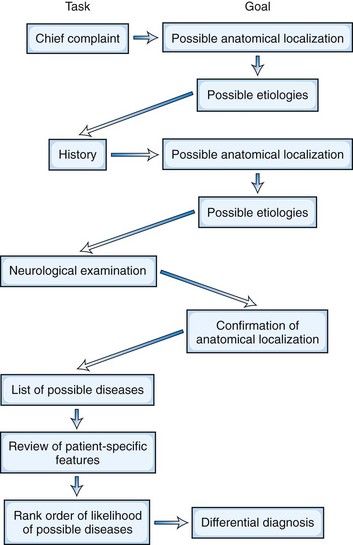

This diagnostic process consists of a series of steps, as depicted in Fig. 1.1. Although standard teaching is that the patient should be allowed to provide the history in his or her own words, the process also involves active questioning of the patient to elicit pertinent information. At each step, the neurologist should consider the possible anatomical localizations and particularly the etiology of the symptoms (see Fig. 1.1). From the patient’s chief complaint and a detailed history, an astute neurologist can derive clues that lead first to a hypothesis about the location and then to a hypothesis about the etiology of the neurological lesion. From these hypotheses, the experienced neurologist can predict what neurological abnormalities should be present and what should be absent, thereby allowing confirmation of the site of the dysfunction. Alternatively, analysis of the history may suggest two or more possible anatomical locations and diseases, each with a different predicted constellation of neurological signs. The findings on neurological examination can be used to determine which of these various possibilities is the most likely. To achieve a diagnosis, the neurologist needs to have a good knowledge of not only the anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry of the nervous system but also of the clinical features and pathology of the neurological diseases.

Review of Patient-Specific Information

Examination

Neurological Examination

Neurological examination starts during the interview. A patient’s lack of facial expression (hypomimia) may suggest parkinsonism or depression, whereas a worried or astonished expression may suggest progressive supranuclear palsy. Unilateral ptosis may suggest myasthenia gravis or a brainstem lesion. The pattern of speech may suggest dysarthria, aphasia, or spasmodic dysphonia. The presence of abnormal involuntary movements may indicate an underlying movement disorder. Neurologist trainees must be able to perform and understand the complete neurological examination, in which every central nervous system region, peripheral nerve, muscle, sensory modality, and reflex is tested. However, the full neurological examination is too lengthy to perform in practice. Instead, the experienced neurologist uses the focused neurological examination to examine in detail the neurological functions relevant to the history and then performs a screening neurological examination to check the remaining parts of the nervous system. This approach should confirm, refute, or modify the initial hypotheses of disease location and causation derived from the history (see Fig. 1.1).

The screening neurological examination (Table 1.1) is designed for quick evaluation of the mental status, cranial nerves, motor system (strength, muscle tone, presence of involuntary movements, and postures), coordination, gait and balance, tendon reflexes, and sensation. More complex functions are tested first; if these are performed well, then it may not be necessary to test the component functions. The patient who can walk heel-to-toe (tandem gait) does not have a significant disturbance of the cerebellum or of joint position sensation. Similarly, the patient who can do a pushup, rise from the floor without using the hands, and walk on toes and heels will have normal limb strength when each muscle group is individually tested. Asking the patient to hold the arms extended in supination in front of the body with the eyes open allows evaluation of strength and posture. It also may reveal involuntary movements such as tremor, dystonia, myoclonus, or chorea. A weak arm is expected to show a downward or pronator drift. Repeating the maneuver with the eyes closed allows assessment of joint position sensation.

| Examination Component | Description/Observation/Maneuver |

|---|---|

| Mental status | Assessed while recording the history |

| Cranial nerves: | |

| CN I | Should be tested in all persons who experience spontaneous loss of smell, in patients suspected to have Parkinson disease, and in patients who have suffered head injury |

| CN II | Each eye: |

| Gross visual acuity | |

| Visual fields by confrontation | |

| Funduscopy | |

| CN III, IV, VI | Horizontal and vertical eye movements |

| Pupillary response to light | |

| Presence of nystagmus or other ocular oscillations | |

| CN V | Pinprick and touch sensation on face, corneal reflex |

| CN VII | Close eyes, show teeth |

| CN VIII | Perception of whispered voice in each ear or rubbing of fingers; if hearing is impaired, look in external auditory canals, and use tuning fork for lateralization and bone-versus-air sound conduction |

| CN IX, X | Palate lifts in midline, gag reflex present |

| CN XI | Shrug shoulders |

| CN XII | Protrude tongue |

| Limbs | Separate testing of each limb: |

| Presence of involuntary movements | |

| Muscle mass (atrophy, hypertrophy) and look for fasciculations | |

| Muscle tone in response to passive flexion and extension | |

| Power of main muscle groups | |

| Coordination | |

| Finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin testing | |

| Performance of rapid alternating movements | |

| Tendon reflexes | |

| Plantar responses | |

| Pinprick and light touch on hands and feet | |

| Double simultaneous stimuli on hands and feet | |

| Joint position sense in hallux and index finger | |

| Vibration sense at ankle and index finger | |

| Gait and balance | Spontaneous gait should be observed; stance, base, cadence, arm swing, tandem gait should be noted |

| Postural stability should be assessed by the pull test | |

| Romberg test | Stand with eyes open and then closed |

Assessment of the Cause of the Patient’s Symptoms

Anatomical Localization

Hypotheses about lesion localization, neurological systems involved, and pathology of the disorder can be formed once the history is complete (see Fig. 1.1). The neurologist then uses the examination findings to confirm the localization of the lesion before trying to determine its cause. The initial question is whether the disease is in the brain, spinal cord, peripheral nerves, neuromuscular junctions, or muscles. Then it must be established whether the disorder is focal, multifocal, or systemic. A system disorder is a disease that causes degeneration of one part of the nervous system while sparing other parts of the nervous system. For instance, degeneration of the corticospinal tracts and spinal motor neurons with sparing of the sensory pathways of the central and peripheral nervous systems is the hallmark of the system degeneration termed motor neuron disease, or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Multiple system atrophy is another example of a system degeneration characterized by slowness of movement (parkinsonism), ataxia, and dysautonomia.

Differential Diagnosis

Once the likely site of the lesion is identified, the next step is to generate a list of diseases or conditions that may be responsible for the patient’s symptoms and signs—the differential diagnosis (see Fig. 1.1). The experienced neurologist automatically first considers the most likely causes, followed by less common causes. The beginner is happy to generate a list of the main causes of the signs and symptoms in whatever order they come to mind. Experience indicates the most likely causes based on specific patient characteristics, the portions of the nervous system affected, and the relative frequency of each disease. An important point is that rare presentations of common diseases are more common than common presentations of rare diseases. Equally important, the neurologist must be vigilant to including in differential diagnosis less likely disorders that if overlooked can cause significant morbidity and/or mortality. A proper differential diagnosis list should include the most likely causes of the patient’s signs and symptoms as well as the most ominous.

Laboratory Investigations

Sometimes the neurological diagnosis can be made without any laboratory investigations. This is true for a clear-cut case of Parkinson disease, myasthenia gravis, or multiple sclerosis. Nevertheless, even in these situations, appropriate laboratory documentation is important for other physicians who will see the patient in the future. In other instances, the cause of the disease will be elucidated only by the use of laboratory tests. These tests may in individual cases include hematological and biochemical blood studies; neurophysiological testing (Chapter 32A, Chapter 32B, Chapter 32C, Chapter 32D, Chapter 32E ); neuroimaging (Chapter 33A, Chapter 33B, Chapter 33C, Chapter 33D, Chapter 33E ); organ biopsy; and bacteriological and virological studies. The use of laboratory tests in the diagnosis of neurological diseases is considered more fully in Chapter 31.

Management of Neurological Disorders

Not all diseases are curable. Even if a disease is incurable, however, the physician will be able to reduce the patient’s discomfort and assist the patient and family in managing the disease. Understanding a neurological disease is a science. Diagnosing a neurological disease is a combination of science and experience. Managing a neurological disease is an art, an introduction to which is provided in Chapter 43.