CHAPTER 52 Diagnosis and Classification of Seizures and Epilepsy

Epilepsy is perhaps the most complex neurological disorder from a clinical and pathophysiologic perspective. Many distinct molecular changes in neurons and glia can cause seizures,1 and seizures occurring in specific neuronal networks manifest very different clinical symptoms and signs. In fact, there are many different epilepsy syndromes, each with multiple neurobiologic origins.2 For example, juvenile myoclonic epilepsy is now understood to be associated with mutations on several different chromosomes.3 Complex partial seizures of temporal lobe origin4 may be caused by mesial temporal sclerosis,5,6 developmental malformations,7,8 brain injury, specific genetic mutations, or possibly a combination of these causes.9 One of the major challenges of contemporary neuroscience is to better understand the ways in which the clinical manifestations of the epilepsies represent underlying structural, physiologic, and genetic alterations.

The epilepsies have importance for public health in that they are among the most common disabling neurological disorders occurring across the life span.10–12 The prevalence of epilepsy is estimated to be about 1% of the U.S. population.13 The World Health Organization reports that more than 100 million people are affected by epilepsy worldwide.14 It is noteworthy that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention emphasizes the lack of research on prevalence and incidence and recently stated that “epidemiological and surveillance data on epilepsy are limited” (www.cdc.gov/Epilepsy/).

Although earlier clinical studies suggested that more than 85% of patients with epilepsy have “adequate” seizure control with antiepileptic drugs,15,16 more recent data indicate that in 35% to 40%, the available medications will not fully control the epilepsy.13,17 In a Scottish study of more than 470 patients with recently diagnosed epilepsy, about 35% had a seizure during the most recent year of follow-up after a mean of 5 years of treatment. Furthermore, in only 11% was the epilepsy ever fully controlled with subsequent medications after the first antiepileptic drug failed.17 A recent population-based study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that included 120,000 people from 19 states found results that supported the Scottish data: 44% of patients with epilepsy who were currently taking medications had at least one seizure during the past 3 months.13 Because the most important initial steps in effective treatment of epilepsy involve accurate diagnosis and subsequent selection of appropriate antiepileptic drugs based on seizure type, classification of the epilepsy based on precise history and supportive clinical testing is critical for optimal outcome.18

Seizure and Epilepsy Classification

The Commission on Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) developed a widely used classification system based on review of videotaped seizures at commission workshops.19 This classification system categorizes seizures in a format that facilitates diagnosis, treatment, and communication among medical professionals through standardized nomenclature.

Seizures are divided into two major categories—partial and generalized. Partial seizures are “those in which the first clinical and electrographic changes indicate initial activation of a system of neurons in one hemisphere and are subclassified based on the presence or absence of impairment of consciousness.”19 Simple partial seizures are associated with minimal change in awareness, as indicated clinically by the patient’s complete recollection of the event. Complex partial seizures are characterized by alteration of awareness and amnesia for at least a portion of the seizure. Partial seizures may include signs or symptoms correlating with activation of any brain region—specifically, motor, autonomic, somatosensory, special sensory, or psychic, as elegantly demonstrated by Drs. Penfield and Jasper in their intraoperative stimulation studies of persons with epilepsy.20 Both simple and complex partial seizures can propagate throughout the brain to become secondarily generalized seizures, typically with tonic or clonic motor features (or with both). Generalized seizures are “those in which the first clinical changes indicate initial involvement of both hemispheres.”19 The subclassification of generalized seizures includes absence, myoclonic, clonic, tonic, tonic-clonic, and atonic seizures. The generalized epilepsies, as opposed to generalized seizures, are often divided into primary (idiopathic) and secondary (symptomatic).2 This distinction is useful because the seizures of primary generalized epilepsy are frequently genetic,21,22 are usually limited to childhood or adolescence, and respond readily to certain anticonvulsant medications.23

Knowledge of the frequency of the common causes of epilepsy is necessary when assessing a patient with seizures. Cerebrovascular disease is the most frequently identified cause of epilepsy, followed by developmental disorders, head trauma, brain tumor, infection, and degenerative disorders.24 The proportional incidence of the causes of seizures varies considerably with age, with cerebrovascular disease predominating in senior adults, head trauma and brain tumors more common in adolescents and adults, and developmental and infectious disorders proportionally most frequent in neonates and young children.24

Epilepsy syndromes are disorders associated with specific seizure types, clinical characteristics, and ages at onset. Similar to seizure classifications, the epilepsies are divided into two main categories: localization related and generalized. The ILAE classification system for epileptic syndromes is summarized in Table 52-1.2

TABLE 52-1 International Classification of the Epilepsies and Epileptic Syndromes

|

1 Localization-related (focal, local, partial) epilepsies and syndromes

2 Generalized epilepsies and syndromes

3 Epilepsies and syndromes undetermined regarding whether they are focal or generalized

|

Adapted from Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. A revised proposal for the classification of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:268-278.

Diagnosis of Epilepsy

Epilepsy is often operationally defined as two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart. However, the ILAE recently proposed that “epilepsy is a disorder of the brain characterized by an enduring predisposition to generate epileptic seizures and by the neurobiologic, cognitive, psychological, and social consequences of this condition. The definition of epilepsy requires the occurrence of at least one epileptic seizure.”25 For the purposes of this chapter, we will consider epilepsy to be two unprovoked seizures or one unprovoked seizure with additional clinical evidence of increased risk for recurrent seizures. Hence, factors that influence the risk for seizure recurrence will be discussed as they relate to the diagnosis and especially to the decision for treatment to prevent subsequent seizures.

Approach to the First Seizure

Acute Evaluation

The urgent evaluation should include serum glucose, sodium, urea nitrogen, creatinine, and calcium and hepatic enzyme concentrations. Arterial blood pH, oxygen, and carbon dioxide are important to measure. A toxicology screen is necessary if no other cause is readily identified, especially for ethyl alcohol, cocaine, amphetamines, benzodiazepines, opioids, phencyclidine, tricyclic antidepressants, and antipsychotic drugs.26 Hypothyroidism with myxedema coma has been associated with seizures in rare cases.27

Brain imaging, preferably computed tomography (CT) in view of its rapid availability at most centers, is necessary to exclude a structural cerebral abnormality such as hemorrhage, tumor, abscess, or contusion.28 If significant temperature elevation, nuchal rigidity, leukocytosis, or other signs of possible central nervous system inflammation are present, a lumbar puncture is required to exclude infection or subarachnoid hemorrhage. If the patient has a possible history of seizures, anticonvulsant medications should be identified and serum concentrations determined.

Decreased responsiveness or unusual behavior may be the only indication of a persistent seizure.29 An urgent EEG is therefore recommended for any patient whose mentation does not begin to normalize within minutes after a witnessed seizure. Furthermore, an EEG should be considered for any patient without a clearly defined cause of the altered mental status. If “subclinical” seizures are a possible cause of the confusion or abnormal behavior and the EEG is not diagnostic, intravenous injection of a short-acting benzodiazepine such as lorazepam may support the diagnosis if clinical improvement is observed soon after administration.29 Change in the EEG pattern after injection does not confirm that a rhythmic or semirhythmic pattern was a seizure; in many cases, this can be determined only by correlative improvement in the mental status examination.30

Seizure Evaluation in the Ambulatory Setting

A complete history of the event from both the patient and a witness is frequently the most helpful diagnostic tool.31 An epigastric, olfactory, or experiential (psychic) aura suggests a partial seizure of temporal lobe onset,32–35 for example, whereas generalized clonic activity immediately preceding the tonic-clonic phase may indicate a primary generalized epilepsy.36 The clinical history may be ambiguous or suggest multiple possible diagnoses, however, including cardiac syncope, dysautonomia, conversion disorder, or panic attacks. In this situation, the physician must use diagnostic tests judiciously to make a definitive diagnosis and exclude progressive or potentially life-threatening disorders expeditiously. The two most helpful tests for achieving these goals in the ambulatory setting are the EEG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).37 I recommend that an EEG be obtained for every patient in whom a seizure is a reasonable diagnosis. MRI is also recommended for these patients unless the clinical history, family history, and EEG strongly indicate a primary generalized epilepsy or a definite nontraumatic provocation such as transient hypoglycemia is known. If a cardiac cause is suspected, appropriate testing or referral should be requested.

Components of the Seizure Experience

Before beginning the discussion of symptoms and changes in behavior (i.e., semiology) in patients with seizures arising from different regions of the brain, it is critically important to recognize that many patients are amnestic for at least a component of their seizures. Blum and colleagues initially reported that patients undergoing video-EEG monitoring were unable to state that they had experienced a seizure after 30% to 50% of partial seizures or generalized tonic-clonic seizures.38 Although this is counterintuitive for many clinicians, the observation has now been replicated in subsequent studies.39,40 These results indicate that self-reported seizure rates in the outpatient clinic can be as misleading as they are helpful in assessing the severity of the epilepsy or outcome after treatment. A thorough history of potential clues to seizure occurrences, supplemented by reports from family, friends, and coworkers, is required to optimize care.

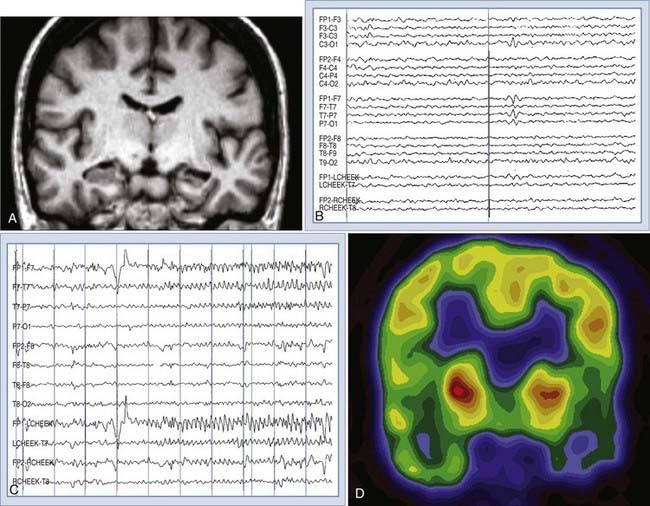

Auras, or simple partial seizures, are often classified by the type of symptoms experienced during the ictal event. For example, the most common symptoms in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy are categorized as visceral/abdominal, psychic, autonomic, somatosensory, special sensory, and visual.32–3541 Specific examples are listed in Figure 52-1. The visceral symptoms may be an ascending sense of constriction or warmth in the abdominal region, which is sometimes described in the literature as an “epigastric rising sensation.” This rising sensation may be difficult for some patients to describe, and the autonomic aspects of the feeling often lead to descriptions such as “I feel like I am dropping quickly in an elevator” or “it feels like the drop on a rollercoaster ride.” The psychic symptoms are most often intense déjà vu, but patients may simply describe a sense that they know what is about to happen. Other psychic symptoms include a sense of dissociation from the environment, depersonalization, or a sense of never being in a familiar place (jamais vu). Common special sensory symptoms are olfactory or less frequently gustatory. Visual symptoms may be formed or unformed hallucinations or visual distortion such as change in size or apparent speed of motion. It is important to understand that seizures arising from the region of the visual cortex my not have visual auras and that visual auras can occur with seizures beginning in areas other than the occipital lobe. An uncommon but well-described visual symptom is the sensation of watching a movie, which may localize to the mesial temporal region. Somatosensory auras are typically positive, such as a tingling or electrical sensation, and are contralateral to a parietal epileptogenic region; however, bilateral and ipsilateral somatosensory auras have been reported in patients with insular42,43 and mesial frontal seizures.44

Clinical Semiology

Specific behavioral changes can be used to localize brain regions involved in a seizure.45,46 For example, a common pattern of movements in a complex partial seizure of mesial temporal lobe origin is ipsilateral motor automatisms (e.g., tapping, patting, or rubbing movements) and contralateral dystonic flexor posturing of the wrist and hand.47 Oral automatisms such as lip smacking, licking, or repetitive swallowing are also common in temporal lobe seizures. Complete behavior arrest is reportedly more frequently associated with temporal lobe than with frontal lobe seizures. Focal tonic or clonic motor seizures are typical of lateral premotor seizures, and hypermotor/frenetic (“motor agitation”) behavior is more common with orbitofrontal or frontopolar seizures.45 Partial abduction of the arms with tonic stiffening is typical of supplementary sensorimotor area seizures, although fencer posturing has been considered a classic movement.48

Physical Examination

Although the findings on physical and neurological examination are frequently normal in persons with epilepsy, some neurological syndromes are often associated with seizures and specific physical abnormalities. For example, tuberous sclerosis complex has a prevalence of epilepsy of 78% and is characterized by facial angiofibromas, hypomelanotic macules, shagreen patches, ungual fibromas, and retinal hamartomas.49,50 Patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 have an increased incidence of seizures (but lower than in patients with tuberous sclerosis) and clinical examination findings of café au lait spots, axillary freckling, cutaneous neurofibromas, and iris hamartomas (Lisch nodules).49,50 A thorough cutaneous and retinal examination should therefore be performed at the initial evaluation of all persons with a history of a seizure or epilepsy.

An interesting, but frequently overlooked clinical finding in temporal lobe epilepsy is asymmetric facial movement with spontaneous smiling.51,52 The asymmetry may not be present with volitional face movement and is accentuated with laughing. It is present on the side of the face contralateral to the epileptogenic region in more than 25% of persons with mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. The presumed mechanism of this finding is amygdala dysfunction resulting in an abnormal emotional motor response.51

Electroencephalography

EEG is an indispensable test to support the diagnosis of seizures, as well as accurately classify the epileptic syndrome. The typical EEG abnormalities seen in various seizure types are described in this section. The sensitivity of a single EEG recording for identifying specific epileptiform abnormalities is about 50%, but it increases to greater than 90% with the third recording.53 The specificity of the EEG depends, to a large extent, on the interpreter; utmost care always should be taken to not misinterpret normal variants as epileptiform abnormalities.54 A typical interictal sharp wave in localization-related epilepsy of mesial temporal origin is displayed in Figure 52-1. The reader is referred to more detailed review for additional information regarding EEG abnormalities in specific epilepsy syndromes.55,56

Neuroimaging

MRI has dramatically improved the imaging of normal and pathologic brain structures. Although CT remains a useful tool, especially in the acute setting or when imaging calcified structures, the limited resolution and bone artifact are problematic when assessing patients with focal seizures. The first goal of neuroimaging of patients with seizures is to exclude a progressive or dangerous lesion such as a tumor or vascular malformation. Several studies have shown MRI to be superior to CT in identifying small lesions57–59; MRI is therefore recommended, when available, for all patients with suspected partial seizures.

MRI is a dynamic, rapidly improving technology. The definition of the optimal MRI method for evaluation of patients with seizures is therefore changing continually. In general, T1-weighted scans with short repetition time/echo time (TR/TE) demonstrate anatomic relationships with superior resolution, whereas T2-weighted long TR/TE sequences are more sensitive for revealing focal pathology. New strategies such as “short flip angle” scans have been suggested to identify small calcifications or hemorrhages. Recent reviews are suggested for a more detailed discussion of MRI technology for imaging patients with epilepsy.60–63

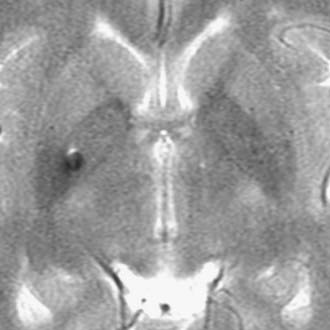

Although broad anatomic coverage is necessary to maximize sensitivity in most MRI screening examinations, more detailed and specific imaging is useful in certain situations. Specifically, because the temporal lobe is the most frequent site of onset in the majority of patients with partial seizures, attention to the mesial temporal region is advantageous. Mesial temporal sclerosis (MTS) is the most common pathologic substrate found in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. The amygdala appears to be variably involved.64 When atrophy on T1-weighted images and increased signal intensity on T2-weighted images of the hippocampus are used to identify MTS, the sensitivity rages from 80% to 93%, with a specificity of between 86% and 93%.57,65,66 Quantitative T2 relaxometry appears to be a useful technique as well.67 Sensitivity and interobserver reliability are high when these criteria are determined by visual inspection, but quantitative volumetric analysis remains valuable for identifying bilateral MTS and for research studies.68,69 High-resolution MRI may also demonstrate loss of definition of the internal architecture of the sclerotic hippocampus.70 Figure 52-1 shows an example of T1-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI of right hippocampal sclerosis. Imaging of neoplastic and vascular lesions is critically important for many persons with epilepsy, but specific aspects of these abnormalities are reviewed in other chapters.

Blum DE, Eskola J, Bortz JJ, et al. Patient awareness of seizures. Neurology. 1996;47:260-264.

Cascino GD, Jack CRJr, Parisi JE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging–based volume studies in temporal lobe epilepsy: pathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:31-36.

Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1257-1266.

, 1989 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. A revised proposal for the classification of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:268-278.

, 1981 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489-501.

Duncan JS. Imaging and epilepsy. Brain. 1997;120:339-377.

Gilliam F, Wyllie E. Diagnostic testing of seizure disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:61-84.

Glauser TA, Sankar R. Core elements of epilepsy diagnosis and management: expert consensus from the Leadership in Epilepsy, Advocacy, and Development (LEAD) faculty. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3463-3477.

Harden CL, Huff JS, Schwartz TH, et al. Reassessment: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007;69:1772-1780.

Hoppe C, Poepel A, Elger CE. Epilepsy: accuracy of patient seizure counts. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1595-1599.

Janati A, Nowack WJ, Dorsey S, et al. Correlative study of interictal electroencephalogram and aura in complex partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1990;31:41-46.

King MA, Newton MR, Jackson GD, et al. Epileptology of the first-seizure presentation: a clinical, electroencephalographic, and magnetic resonance imaging study of 300 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1998;352:1007-1011.

Kotagal P, Arunkumar G, Hammel J, et al. Complex partial seizures of frontal lobe onset statistical analysis of ictal semiology. Seizure. 2003;12:268-281.

Kotagal P, Lüders HO, Williams G, et al. Psychomotor seizures of temporal lobe onset: analysis of symptom clusters and sequences. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:49-67.

Kuzniecky R, de la Sayette V, Ethier R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in temporal lobe epilepsy: pathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:341-347.

Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314-319.

Manford M, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. An analysis of clinical seizure patterns and their localizing value in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Brain. 1996;119:17-40.

Morris HH3rd, Dinner DS, Lüders H, et al. Supplementary motor seizures: clinical and electroencephalographic findings. Neurology. 1988;38:1075-1082.

O’Brien TJ, Kilpatrick C, Murrie V, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy caused by mesial temporal sclerosis and temporal neocortical lesions. A clinical and electroencephalographic study of 46 pathologically proven cases. Brain. 1996;119:2133-2141.

O’Brien TJ, Mosewich RK, Britton JW, et al. History and seizure semiology in distinguishing frontal lobe seizures and temporal lobe seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2008;82:177-182.

Palmini A, Gloor P. The localizing value of auras in partial seizures: a prospective and retrospective study. Neurology. 1992;42:801-808.

Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain. Boston: Little, Brown; 1954.

Remillard GM, Andermann F, Rhi-Sausi A, et al. Facial asymmetry in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. A clinical sign useful in the lateralization of temporal epileptogenic foci. Neurology. 1977;27:109-114.

Ryvlin P, Minotti L, Demarquay G, et al. Nocturnal hypermotor seizures, suggesting frontal lobe epilepsy, can originate in the insula. Epilepsia. 2006;47:755-765.

Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff RM. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting the diagnosis of epilepsy: an operational curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28:331-334.

Taylor DC, Lochery M. Temporal lobe epilepsy: origin and significance of simple and complex auras. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:673-681.

Tuxhorn IE. Somatosensory auras in focal epilepsy: a clinical, video EEG and MRI study. Seizure. 2005;14:262-268.

Van Paesschen W, King MD, Duncan JS, et al. The amygdala and temporal lobe simple partial seizures: a prospective and quantitative MRI study. Epilepsia. 2001;42:857-862.

1 Chang BS, Lowenstein DH. Epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1257-1266.

2 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. A revised proposal for the classification of epilepsy and epileptic syndromes. Epilepsia. 1989;30:268-278.

3 Greenberg DA, Durner M, Keddache M, et al. Reproducibility and complications in gene searches: linkage on chromosome 6, heterogeneity, association, and maternal inheritance in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;66:508-516.

4 O’Brien TJ, Kilpatrick C, Murrie V, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy caused by mesial temporal sclerosis and temporal neocortical lesions. A clinical and electroencephalographic study of 46 pathologically proven cases. Brain. 1996;119:2133-2141.

5 Abou-Khalil B, Andermann E, Andermann F, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy after prolonged febrile convulsions: excellent outcome after surgical treatment. Epilepsia. 1993;34:878-883.

6 Mohamed A, Wyllie E, Ruggieri P, et al. Temporal lobe epilepsy due to hippocampal sclerosis in pediatric candidates for epilepsy surgery. Neurology. 2001;56:1643-1649.

7 Kuzniecky R, Ho SS, Martin R, et al. Temporal lobe developmental malformations and hippocampal sclerosis: epilepsy surgical outcome. Neurology. 1999;52:479-484.

8 Ho SS, Kuzniecky RI, Gilliam F, et al. Temporal lobe developmental malformations and epilepsy: dual pathology and bilateral hippocampal abnormalities. Neurology. 1998;50:748-754.

9 Salzmann A, Perroud N, Crespel A, et al. Candidate genes for temporal lobe epilepsy: a replication study. Neurol Sci. 2008;29:397-403.

10 Lennox WG. Epilepsy; a problem in public health. Am J Public Health Nations Health. 1951;41:533-536.

11 Kobau R, Zahran H, Grant D, et al. Prevalence of active epilepsy and health-related quality of life among adults with self-reported epilepsy in California: California Health Interview Survey, 2003. Epilepsia. 2007;48:1904-1913.

12 Kobau R, DiIorio CA, Price PH, et al. Prevalence of epilepsy and health status of adults with epilepsy in Georgia and Tennessee: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2002. Epilepsy Behav. 2004;5:358-366.

13 Kobau R, Zahran H, Thurman DJ, et al. Epilepsy surveillance among adults—19 States, Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2005. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(6):1-20.

14 Reynolds EH. The ILAE/IBE/WHO Global Campaign Against Epilepsy: bringing epilepsy “out of the shadows”. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1(4):S3-S8.

15 Hauser WA. The natural history of drug resistant epilepsy: epidemiologic considerations. Epilepsy Res Suppl. 1992;5:25-28.

16 Hauser E, Freilinger M, Seidl R, et al. Prognosis of childhood epilepsy in newly referred patients. J Child Neurol. 1996;11:201-204.

17 Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314-319.

18 French JA, Pedley TA. Clinical practice. Initial management of epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:166-176.

19 Commission on the Classification and Terminology of the International League Against Epilepsy. Proposal for revised clinical and electroencephalographic classification of epileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1981;22:489-501.

20 Penfield W, Jasper H. Epilepsy and the Functional Anatomy of the Human Brain. Boston: Little, Brown; 1954.

21 Helbig I, Mefford HC, Sharp AJ, et al. 15q13.3 microdeletions increase risk of idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2009;41:160-162.

22 Andrade DM, Minassian BA. Genetics of epilepsies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2007;7:727-734.

23 Valentin A, Hindocha N, Osei-Lah A, et al. Idiopathic generalized epilepsy with absences: syndrome classification. Epilepsia. 2007;48:2187-2190.

24 Annegers JF, Rocca WA, Hauser WA. Causes of epilepsy: contributions of the Rochester epidemiology project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:570-575.

25 Fisher RS, van Emde Boas W, Blume W, et al. Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the International League Against Epilepsy (ILAE) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (IBE). Epilepsia. 2005;46:470-472.

26 Alldredge BK, Lowenstein DH, Simon RP. Seizures associated with recreational drug abuse. Neurology. 1989;39:1037-1039.

27 Evans EC. Neurologic complications of myxedema: convulsions. Ann Intern Med. 1960;52:434-444.

28 Harden CL, Huff JS, Schwartz TH, et al. Reassessment: neuroimaging in the emergency patient presenting with seizure (an evidence-based review): report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2007;69:1772-1780.

29 Privitera M, Hoffman M, Moore JL, et al. EEG detection of nontonic-clonic status epilepticus in patients with altered consciousness. Epilepsy Res. 1994;18:155-166.

30 Chong DJ, Hirsch LJ. Which EEG patterns warrant treatment in the critically ill? Reviewing the evidence for treatment of periodic epileptiform discharges and related patterns. J Clin Neurophysiol. 2005;22:79-91.

31 O’Brien TJ, Mosewich RK, Britton JW, et al. History and seizure semiology in distinguishing frontal lobe seizures and temporal lobe seizures. Epilepsy Res. 2008;82:177-182.

32 Alvarez-Silva S, Alvarez-Silva I, Alvarez-Rodriguez J, et al. Epileptic consciousness: concept and meaning of aura. Epilepsy Behav. 2006;8:527-533.

33 Janati A, Nowack WJ, Dorsey S, et al. Correlative study of interictal electroencephalogram and aura in complex partial seizures. Epilepsia. 1990;31:41-46.

34 Van Paesschen W, King MD, Duncan JS, et al. The amygdala and temporal lobe simple partial seizures: a prospective and quantitative MRI study. Epilepsia. 2001;42:857-862.

35 Palmini A, Gloor P. The localizing value of auras in partial seizures: a prospective and retrospective study. Neurology. 1992;42:801-808.

36 Park KI, Lee SK, Chu K, et al. The value of video-EEG monitoring to diagnose juvenile myoclonic epilepsy. Seizure. 2009;18:94-99.

37 Glauser TA, Sankar R. Core elements of epilepsy diagnosis and management: expert consensus from the Leadership in Epilepsy, Advocacy, and Development (LEAD) faculty. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3463-3477.

38 Blum DE, Eskola J, Bortz JJ, et al. Patient awareness of seizures. Neurology. 1996;47:260-264.

39 Hoppe C, Poepel A, Elger CE. Epilepsy: accuracy of patient seizure counts. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1595-1599.

40 Palmini AL, Gloor P, Jones-Gotman M. Pure amnestic seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Definition, clinical symptomatology and functional anatomical considerations. Brain. 1992;115:749-769.

41 Taylor DC, Lochery M. Temporal lobe epilepsy: origin and significance of simple and complex auras. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1987;50:673-681.

42 Ostrowsky K, Magnin M, Ryvlin P, et al. Representation of pain and somatic sensation in the human insula: a study of responses to direct electrical cortical stimulation. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:376-385.

43 Ryvlin P, Minotti L, Demarquay G, et al. Nocturnal hypermotor seizures, suggesting frontal lobe epilepsy, can originate in the insula. Epilepsia. 2006;47:755-765.

44 Tuxhorn IE. Somatosensory auras in focal epilepsy: a clinical, video EEG and MRI study. Seizure. 2005;14:262-268.

45 Manford M, Fish DR, Shorvon SD. An analysis of clinical seizure patterns and their localizing value in frontal and temporal lobe epilepsies. Brain. 1996;119:17-40.

46 Kotagal P, Arunkumar G, Hammel J, et al. Complex partial seizures of frontal lobe onset statistical analysis of ictal semiology. Seizure. 2003;12:268-281.

47 Kotagal P, Lüders HO, Williams G, et al. Psychomotor seizures of temporal lobe onset: analysis of symptom clusters and sequences. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:49-67.

48 Morris HH3rd, Dinner DS, Lüders H, et al. Supplementary motor seizures: clinical and electroencephalographic findings. Neurology. 1988;38:1075-1082.

49 Cross JH. Neurocutaneous syndromes and epilepsy—issues in diagnosis and management. Epilepsia. 2005;46(suppl 10):17-23.

50 Kotagal P, Rothner AD. Epilepsy in the setting of neurocutaneous syndromes. Epilepsia. 1993;34(suppl 3):S71-S78.

51 Remillard GM, Andermann F, Rhi-Sausi A, et al. Facial asymmetry in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. A clinical sign useful in the lateralization of temporal epileptogenic foci. Neurology. 1977;27:109-114.

52 Cascino GD, Luckstein RR, Sharbrough FW, et al. Facial asymmetry, hippocampal pathology, and remote symptomatic seizures: a temporal lobe epileptic syndrome. Neurology. 1993;43:725-727.

53 Salinsky M, Kanter R, Dasheiff RM. Effectiveness of multiple EEGs in supporting the diagnosis of epilepsy: an operational curve. Epilepsia. 1987;28:331-334.

54 Klass DW, Westmoreland BF. Nonepileptogenic epileptiform electroencephalographic activity. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:627-635.

55 Gilliam F, Wyllie E. Diagnostic testing of seizure disorders. Neurol Clin. 1996;14:61-84.

56 Westmoreland BF. The electroencephalogram in patients with epilepsy. Neurol Clin. 1985;3:599-613.

57 Kuzniecky R, de la Sayette V, Ethier R, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in temporal lobe epilepsy: pathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:341-347.

58 Theodore WH, Dorwart R, Holmes M, et al. Neuroimaging in refractory partial seizures: comparison of PET, CT, and MRI. Neurology. 1986;36:750-759.

59 King MA, Newton MR, Jackson GD, et al. Epileptology of the first-seizure presentation: a clinical, electroencephalographic, and magnetic resonance imaging study of 300 consecutive patients. Lancet. 1998;352:1007-1011.

60 Cascino GD. Neuroimaging in epilepsy: diagnostic strategies in partial epilepsy. Semin Neurol. 2008;28:523-532.

61 Duncan JS. Neuroimaging methods to evaluate the etiology and consequences of epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2002;50:131-140.

62 Duncan JS. Imaging and epilepsy. Brain. 1997;120:339-377.

63 Kuzniecky RI. Neuroimaging of epilepsy: advances and practical applications. Rev Neurol Dis. 2004;1:179-189.

64 Cendes F, Andermann F, Gloor P, et al. MRI volumetric measurement of amygdala and hippocampus in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurology. 1993;43:719-725.

65 Kuzniecky RI, Bilir E, Gilliam F, et al. Multimodality MRI in mesial temporal sclerosis: relative sensitivity and specificity. Neurology. 1997;49:774-778.

66 Jackson GD, Berkovic SF, Tress BM, et al. Hippocampal sclerosis can be reliably detected by magnetic resonance imaging. Neurology. 1990;40:1869-1875.

67 Briellmann RS, Syngeniotis A, Fleming S, et al. Increased anterior temporal lobe T2 times in cases of hippocampal sclerosis: a multi-echo T2 relaxometry study at 3 T. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2004;25:389-394.

68 Cascino GD, Jack CRJr, Parisi JE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging–based volume studies in temporal lobe epilepsy: pathological correlations. Ann Neurol. 1991;30:31-36.

69 Jack CRJr, Sharbrough FW, Cascino GD, et al. Magnetic resonance image–based hippocampal volumetry: correlation with outcome after temporal lobectomy. Ann Neurol. 1992;31:138-146.

70 Jackson GD, Kuzniecky RI, Cascino GD. Hippocampal sclerosis without detectable hippocampal atrophy. Neurology. 1994;44:42-46.