chapter 26 Diabetes

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

Diabetes mellitus is classified into several types:

RISK FACTORS AND PRIMARY PREVENTION

AETIOLOGY

Type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes constitutes around 5–10% of diabetes cases. Aetiological factors are the following:

Type 2 diabetes

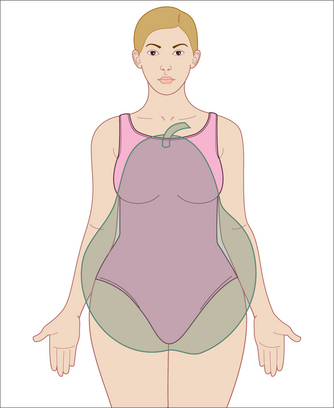

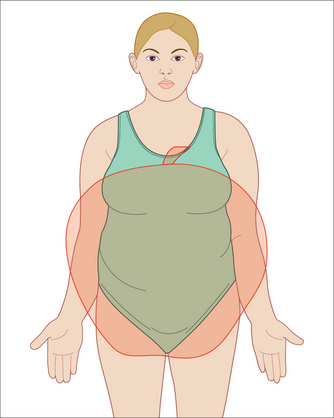

Type 2 diabetes, being strongly related to lifestyle, is most common in affluent countries, where there is abundant food along with sedentary occupations and a significant uptake of labour-saving devices. Within those affluent countries, however, type 2 diabetes is more common among lower socioeconomic groups, where poor-quality food, social disadvantage and poorer education have their impact. In either case, the cause of the condition being largely lifestyle related also means that it is preventable and can be managed with appropriate and sustained lifestyle change. To illustrate how important simple lifestyle factors are in diabetes prevention, never smoking, having a BMI < 30, exercising moderately for 3.5 hours per week and following a few healthy dietary principles (high intake of fruit, vegetables and wholegrain bread, and low meat consumption) compared with not having any of those four factors was associated with a 93% reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes over 8 years of follow-up.3

PRIMARY PREVENTION

Nutritional and environmental

Pre-conception counselling and pregnancy

Maternal malnutrition and overnutrition during pregnancy are associated with subsequent type 2 diabetes in the offspring.5 Primary prevention needs to start with pre-conception counselling of women planning pregnancy, with advice on exercise and nutrition to maintain optimal weight and nutritional status during the pregnancy.

Infant supplements

A systematic review of observational studies found that giving infants vitamin D supplements could protect them from type 1 diabetes.6 Infants given the supplement had an almost 30% reduced risk of diabetes compared with those who were not supplemented. This is particularly important in breastfed infants of vitamin-D-deficient mothers.

Case detection

Proactive screening of asymptomatic patients

The following groups of asymptomatic patients should be tested:7

Blood glucose level

Interpretation of blood glucose level (BGL) results:

Re-testing should be performed under the following circumstances:

MANAGEMENT

INITIAL ASSESSMENT

History

Examination

Comprehensive physical examination, including:

INITIAL MANAGEMENT

A decision needs to be made about appropriate medication and supplements (see below).

ONGOING MANAGEMENT

Goals of management

The ACCORD study reported by the NIH in 2008 suggests that aiming for stricter control for type 2 diabetics in the range of a HbA1c of ≤ 6.5 was associated with higher mortality than those controlled in the range of 7.0–7.9.8

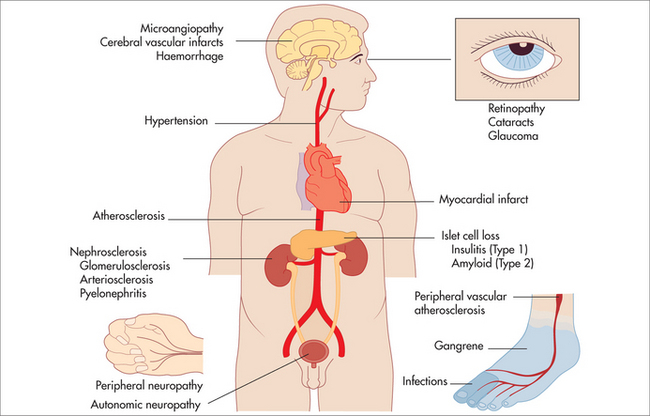

Secondary prevention

Secondary prevention in diabetes refers to the management of risk factors, and prevention or early intervention in the event of complications (see Box 26.2).

Diet

Principles of dietary management in diabetes:

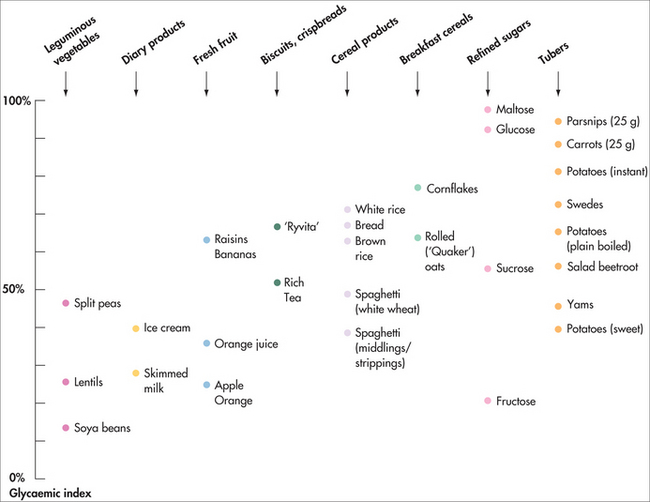

Glycaemic index

A low-GI diet is recommended for primary prevention of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease, in the management of diabetes and prediabetes and for maintenance of general health. A low-GI diet is part of the story, but the glycaemic load is an important marker of how good or bad a food is for blood glucose control, insulin level and diabetic control. The high GI of foods such as parsnip and dates is offset by their high dietary fibre content, meaning that they have a relatively low total glycaemic load. Hence, although many fruits and vegetables have a relatively high sucrose content, they are nevertheless good for diabetics because of their high natural levels of fibre. Sucrose, a form of sugar made up of glucose and fructose, has a moderate GI. Many commercially produced foods contain high levels of refined sucrose (sugar) but very low fibre content and therefore have a high glycaemic load. Hence, it is not ‘sugar’ per se that is problematic for diabetics, but refined sugar. Many commercially produced fruit-juice drinks and foods are labelled as having ‘no added sugar’ but actually have high levels of sucrose through the addition of things such as fruit juice concentrate or corn syrup. Many ‘low-fat’ foods also masquerade as being healthy for diabetics but often have high levels of refined sucrose. It is therefore important for patients to cultivate their ability to read and understand the contents on food labels in order to understand what they are eating. A dietician can help with this.

Supplements

Fish oil

Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) supplementation in type 2 diabetes lowers triglycerides and VLDL cholesterol, but may raise LDL cholesterol (although results were non-significant in subgroups) and has no statistically significant effect on glycaemic control or fasting insulin. Trials with vascular events or mortality-defined endpoints are needed. No adverse effects of the intervention were reported.9

B vitamins

Vitamin B1—correction of thiamine deficiency in experimental diabetes by high-dose therapy with thiamine and the thiamine monophosphate prodrug, benfotiamine, was found to prevent multiple mechanisms of biochemical dysfunction: activation of protein kinase C, activation of the hexosamine pathway, increased glycation and oxidative stress. Consequently, the development of incipient diabetic nephropathy, neuropathy and retinopathy was prevented. Both thiamine and benfotiamine produced other remarkable effects in experimental diabetes: marked reversals of increased diuresis and glucosuria without change in glycaemic status. High-dose thiamine also corrected dyslipidaemia in experimental diabetes—normalising cholesterol and triglycerides. Dysfunction of beta-cells and impaired glucose tolerance in thiamine deficiency, and suggestion of a link of impaired glucose tolerance with dietary thiamine, indicates that thiamine therapy may have a future role in prevention of type 2 diabetes.10

Vitamin B3 (nicotinamide)—500 mg daily for a month, followed by 250 mg daily helps reduce BGL in some diabetics. By the time insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM) is diagnosed, 80–90% of pancreatic beta islet cells have already been destroyed. Nicotinamide has been shown to protect pancreatic beta cells from inflammation leading to their destruction and to improve remaining beta cell function after the onset of IDDM.11,12 The extended release form has a lower incidence of flushing as a side effect. Higher doses may cause insulin resistance and increase fasting blood glucose in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), so it should be used with caution in this group of patients.

Vitamin B6—low levels of vitamin B6 are common in people with type 2 diabetes.

Magnesium

Magnesium deficiency is common in people with diabetes and may be protective against the development of early-stage type 2 diabetes in individuals with normal renal function.13

Zinc

Zinc deficiency is common in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes decreases zinc absorption and increases urinary excretion, decreasing total body zinc. It is particularly common in vegetarians. Production, storage and secretion of insulin requires zinc. Zinc supplementation therefore is a reasonable strategy for prevention of zinc deficiency in diabetes.14 Zinc used as therapy in obese women with normal glucose tolerance has been shown to decrease insulin resistance.

Recommendation: 30 mg elemental zinc daily (check renal function).

HERBAL

Gymnema sylvestre

Gymnema sylvestre suppresses perception of ‘sweet’ taste and reduces sweet craving.15 It reduces intestinal absorption of glucose and inhibits active glucose transport in the small intestine, stimulates insulin secretion and increases the number of islets of Langerhans and pancreatic beta cells.16 Doses of hypoglycaemic medication may need to be adjusted, as it can reduce BGL.

Fenugreek

Fenugreek has been used traditionally to regulate BGL levels by delaying glucose absorption and enhancing its utilisation.17 It has mild hypoglycaemic, lipid-lowering and anti-inflammatory effect. Forms and treatment regimens vary. Doses of hypoglycaemic medication may need to be adjusted, as it can reduce BGL.

Dose: 50–100 g seed daily in divided doses with meals, or 1 g/day ethanolic seed extract.

Evening primrose oil

Evening primrose oil is useful in treating mild to moderate diabetic neuropathy.18 It may be combined with fish oil.

Dose: 360–480 mg gamma linoleic acid (GLA) (equivalent to 4–6 × 1 g capsules per day).

MENTAL HEALTH, STRESS AND DIABETES

Diabetes can predispose a patient to poor mental health, and poor mental health can predispose patients to diabetes as well as increasing comorbidity, negatively affecting the person’s lifestyle and also making it harder for patients with diabetes to cope with their condition.

People living with diabetes have at least double the risk of depression compared with individuals without diabetes.20 Depressive symptoms in initially non-diabetic adults have also been shown to be predictive of later development of type 2 diabetes,21 with a 63% increased risk of diabetes in subjects demonstrating depressive symptoms (including recent fatigue, sleep disturbance, feelings of hopelessness, loss of libido and increased irritability) at baseline.

Psychological stress can precipitate a range of autoimmune conditions including type 1 diabetes22 through the process of dysregulation of the immune system. Stress increases blood sugar and fat levels and so can also destabilise type 2 diabetes and increase the chances of diabetic complications such as heart disease. It can also contribute to the destabilisation of diabetes via secondary effects such as:

Research on diabetes shows that stress management leads to a significantly better level of diabetic control and lower rate of complications,23 making for more stable control, healthier lifestyle and better compliance with treatment and monitoring. Stress management is therefore a core element in diabetes management.

Chronic or long-term activation of the stress response leads to high ‘allostatic load’,24 a form of prolonged wear and tear on the body. High allostatic load is found in chronic stress and anxiety, and depression, and is associated with poor immunity, acceleration of atherosclerosis, ‘metabolic syndrome’ and chronically high cortisol levels. Stress in the workplace has been shown to be an important risk factor for metabolic syndrome.25 This is thought to be associated with high basal secretion of cortisol.

YOGA

A systematic review of studies examining the effect of yoga on diabetes suggest beneficial changes in several risk indices, including glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, lipid profiles, anthropometric characteristics, blood pressure, oxidative stress, coagulation profiles, sympathetic activation and pulmonary function, as well as improvement in specific clinical outcomes.26 Yoga may improve risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes, and may have promise for the prevention and management of cardiovascular complications in this population. However, the limitations characterising most studies preclude any firm conclusions being drawn.

MEDICATION

Oral hypoglycaemic agents

INITIATION OF INSULIN

TYPE 1 DIABETES

TYPE 2 DIABETES

The United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS)27 showed that most people with type 2 diabetes will experience progressive pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction despite excellent control, and become refractory to oral hypoglycaemic agents.

A regimen of intermediate-acting insulin (10 units) at bedtime in combination with daytime oral drugs is usually acceptable to patients, simple to start and results in rapid improvement in glycaemic control.28

Insulin can be delivered in syringes, pens or insulin pumps.

1 Hoffman L, Nolan C, Wilson JD, et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus—management guidelines. Med J Aust. 1998;169:93-97.

2 Humber A, Menconi F, Coathers S, et al. Joint genetic susceptibility to type 1 diabetes and autoimmune thyroiditis: from epidemiology to mechanism. Endocr Rev. 2008;29(6):697-725.

3 Ford ES, Bergmann MM, Kröger J, et al. Healthy living is the best revenge: findings from the European Prospective Investigation Into Cancer and Nutrition—Potsdam Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(15):1355-1362.

4 Expert Panel on Detection. Executive summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001;285:2186-2197.

5 Juvanovic L. Nutrition and pregnancy: the link between dietary intake and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2004;4(4):266-272.

6 Zipitis C, Akobeng A. Vitamin D supplementation in early childhood and risk of type 1 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:512-517. Online. Available: http://adc.bmj.com/cgi/content/abstract/adc.2007.128579v1.

7 Evidence-based guideline for case detection and diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Online. Available: http://www.diabetesaustralia.com.au/_lib/doc_pdf/NEBG/CD/Part3-CaseDetection-311201.pdf.

8 National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) Trial. Questions and answers. Online. Available: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/prof/heart/other/accord/q_a.htm.

9 Hartweg J, Perera R, Montori V, et al. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008:1. CD003205

10 Thornalley PJ. The potential role of thiamine (vitamin B1) in diabetic complications. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2005;1(3):287-298.

11 Lampeter EF, Klinghammer A, Scherbaum WA, et al. The Deutche Nicotinamide Intervention Study. DENIS group. Diabetes. 1998;126(4):435-438.

12 Gale EA. Theory and practice of nicotinamide trials in pre-type 1 diabetes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 1996;9(3):375-379.

13 Ruy LR, Willett W, Rimm E, et al. Magnesium intake and risk of type 2 diabetes in men and women. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):134-140.

14 Cunningham JJ, Fu A, Mearkle PL, et al. Hyperzincuria in individuals with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: concurrent zinc status and the effect of high-dose zinc supplementation. Metabolism. 1994;43:1558-1562.

15 Frank RA, Mize SJS, Kennedy LM, et al. The effect of Gymnema sylvestre extracts on the sweetness of eight sweeteners. Chem Senses. 1992;17(5):461-479.

16 Prakash AO, Mathur S, Mathur R, et al. Effect of feeding Gymnema sylvestre leaves on blood glucose in beryllium nitrate treated rats. Ethnopharmacol. 1986;18(2):143-146.

17 Al Habori M, Raman A, Lawrence MJ, et al. In vitro effect of fenugreek extracts on intestinal sodium-dependent glucose uptake and hepatic glycogen phosphorylase A. Int J Exp Diabetes Res. 2001;2(2):91-99.

18 Jamal GA, Carmichael H. The effect of gamma linoleic acid on human diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a double blind placebo-controlled trial. Diabet Med. 1990;7(4):319-323.

19 Nahas R. Complementary and alternative medicine for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(6):591-596.

20 Anderson RJ, Freedland K, Clouse RE, et al. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069-1078.

21 Golden S, Williams JE, Ford DE, et al. Depressive symptoms and the risk of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:429-435.

22 Sepa A, Ludvigsson J. Psychological stress and the risk of diabetes-related autoimmunity: a review article. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2006;13(5/6):301-308.

23 Surwit RS, van Tilburg MA, Zucker N, et al. Stress management improves long-term glycemic control in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(1):30-34.

24 McEwen BS. Protection and damage from acute and chronic stress: allostasis and allostatic overload and relevance to the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1032:1-7.

25 Chandola T, Brunner E, Marmot M. Chronic stress at work and the metabolic syndrome: prospective study. BMJ. 2006;332:521-525.

26 Innes KE, Vincent HK. The influence of yoga-based programs on risk profiles in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4(4):469-486.

27 UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33). Lancet. 1998;352:837-853.

28 Wong J, Yue D. Starting insulin treatment in type 2 diabetes. Australian Prescriber. 2004;27:93-96.