53

Developmental Anomalies

Developmental anomalies are a diverse group of congenital disorders that result from faulty in utero morphogenesis. When they affect the skin, developmental anomalies can range in severity from isolated minor physical findings to potentially life-threatening conditions or cutaneous signs of significant extracutaneous defects.

Midline Lesions of the Nose or Scalp

• A midline mass or pit on the nose or scalp due to a dermoid cyst, cephalocele, nasal glioma, or other heterotopic brain/meningeal tissue (Fig. 53.1) may have a deeper component with intracranial extension.

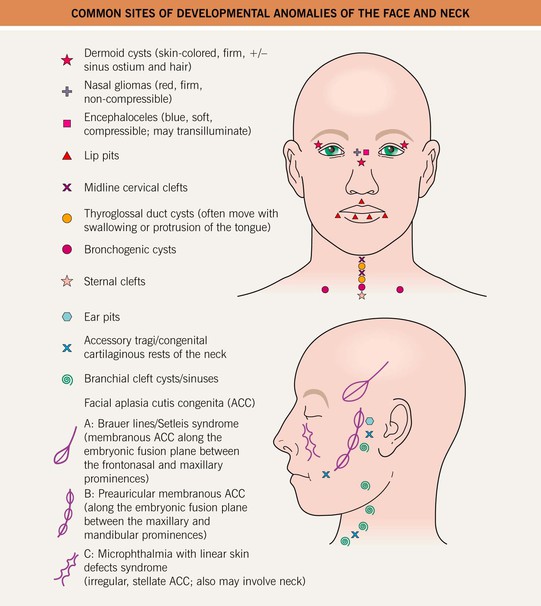

Fig. 53.1 Common sites of developmental anomalies of the face and neck. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• These lesions are typically apparent at birth or during early childhood.

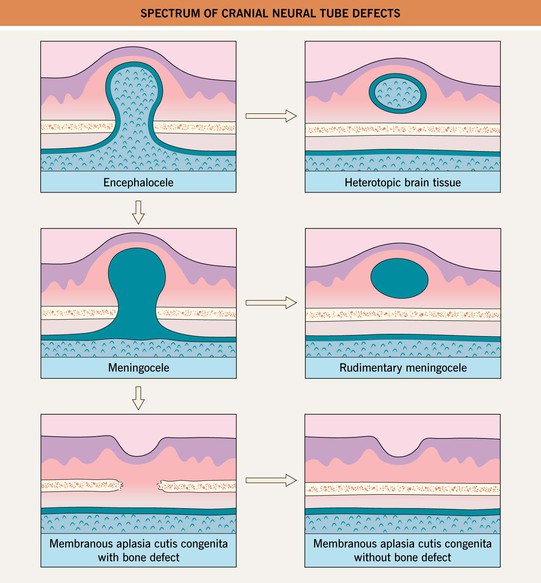

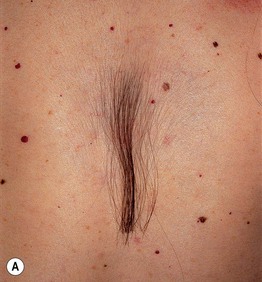

• Hair collar sign: a peripheral ring of long, dark hair often surrounds ectopic neural tissue or membranous aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) on the scalp (Figs. 53.2 and 53.3); the latter is thought to represent a forme fruste of a neural tube defect.

Fig. 53.2 Hair collar sign in membranous aplasia cutis congenita. Note the associated capillary malformation (A) and the bullous appearance (B). A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 53.3 Spectrum of cranial neural tube defects.

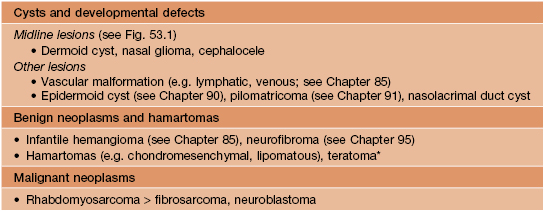

• DDx: outlined in Table 53.1 for nasal masses; epidermoid and pilar cysts for scalp masses (especially in older children and adults).

Table 53.1

The differential diagnosis of nasal masses presenting at birth or during infancy.

* May also be malignant.

Dermoid Cysts

• Result from sequestration of ectodermal tissue along embryonic fusion planes.

• Recognized at birth or when they enlarge or become inflamed during infancy or childhood.

• Most often located around the eyes, especially the lateral eyebrow region (Fig. 53.4); midline lesions on the nose, scalp, or back may have intracranial extension.

Cephaloceles

Nasal Gliomas, Other Heterotopic Brain Tissue, and Rudimentary Meningoceles

• A nasal glioma is a congenital mass of heterotopic brain tissue (HBT) at the nasal root/glabella > intranasally; the skin overlying this firm, noncompressible nodule tends to be red with prominent telangiectasias (mimicking an infantile hemangioma) (Fig. 53.5).

Fig. 53.5 Nasal glioma. A mass was noted on prenatal ultrasound, and this reddish, slightly pedunculated, rubbery nodule was evident at birth. Courtesy, Mary Chang, MD.

• Other HBT and rudimentary meningoceles typically present as a solid or cystic subcutaneous nodule on the midline scalp, often with a blue-red hue, overlying alopecia and a surrounding hair collar (see above); a rudimentary meningocele may have a bullous appearance and can also be located over the spine.

• May have a vestigial fibrous stalk extending into the intracranial space, but lack a connection with the intracranial leptomeninges or CSF (see Fig. 53.3).

Midline Cervical, Sternal, and Supraumbilical Clefts

• A sternal cleft or supraumbilical raphe presents with a band of atrophic (Fig. 53.6), scarred or ulcerated skin; may occur in the setting of PHACE(S) syndrome (posterior fossa malformations; hemangiomas; arterial, cardiac, and eye anomalies; sternal cleft/supraumbilical raphe; see Chapter 85).

Fig. 53.6 Sternal cleft. Note the atrophic skin overlying the defect and prominent veins in the midline chest. Generalized desquamation is also evident in this 1-day-old post-term neonate. She did not develop an infantile hemangioma and had no cardiac defects or other features of PHACE(S) syndrome. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Midline Lesions Overlying the Spine

• Skin lesions associated with spinal dysraphism are presented in Table 53.2 and Fig. 53.7.

Table 53.2

Skin lesions of the spinal axis associated with dysraphism.

The presence of two or more types of lesions increases the risk of a spinal anomaly.

| Lesion | Features |

| Hypertrichosis | A V-shaped patch of long, coarse or silky hair (see Fig. 53.7A,B); ‘faun tail’ |

| Lipomas | Soft subcutaneous mass, asymmetric buttocks, curved gluteal cleft (see Fig. 53.7C); most common sign of spinal dysraphism |

| Dimples | Above the gluteal cleft or >2.5 cm from the anal verge in neonates (see Fig. 53.7C,D); >0.5 cm in size or deep* |

| Dermal sinuses | Hair may be present at the ostium* |

| Acrochordons | May be associated with a dimple or dermal sinus |

| Pseudotails | Caudal protrusion due to prolonged vertebrae or hamartomatous elements, e.g. adipose tissue or cartilage (see Fig. 53.7C,D) |

| True tails | Persistent vestigial appendage with a central core of mature adipose tissue, muscle, blood vessels, and nerves May be capable of spontaneous or reflex motion |

| Infantile hemangiomas | Usually superficial with a segmental pattern (see Fig. 53.7C) and often ulcerated; represents a component of LUMBAR syndrome |

| Telangiectasias | May represent an early, minimal/arrested growth or regressed infantile hemangioma |

| Capillary malformations (CM)** | Typically found together with other skin lesions Cobb syndrome: segmental lesions mimicking a CM or angiokeratomas are part of a metameric arteriovenous malformation involving the spine |

| Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC) | Ulcer, scar, or atrophic skin |

| Connective tissue nevus | Typically found together with other skin lesions |

| Hypo/depigmentation | May represent a nevus depigmentosus (typically found together with other skin lesions) or the residua of ACC |

| Hyperpigmentation | Typically found together with other skin lesions |

| Congenital melanocytic nevi | Spinal dysraphism has been reported in patients with neurocutaneous melanosis |

| Subcutaneous masses | May represent (lipomyelo)meningoceles or teratomas |

* Due to a potential risk of meningitis, these lesions should not be probed.

** The common occipital nevus simplex (‘stork bite’) and lumbosacral capillary stains in the setting of other nevus simplex lesions of the head/neck (but no other lumbosacral skin lesions) are generally not considered to be signs of spinal dysraphism.

LUMBAR, lumbosacral hemangiomas and lipomas; urogenital anomalies and ulceration, myelopathy, bony deformities, anorectal and arterial malformations, renal anomalies.

Fig. 53.7 Skin findings associated with spinal dysraphism. A Circumscribed midline hypertrichosis overlying the lower thoracic spine in a patient with occult dysraphism. The patient periodically clips the distal ends. B V-shaped patch of long, coarse hair on the mid back in a boy born with a large thoracic myelomeningocele. Severe scoliosis remains after multiple surgeries. C This infant with segmental infantile hemangiomas, a dimple, a pseudotail, and a deviated gluteal cleft had an underlying lipomyelomeningocele. D Midline deep sacral dimple located above the gluteal cleft in association with a small pseudotail. In contrast, a shallow dimple within the gluteal cleft is a common finding and not a sign of spinal dysraphism. A, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD; C, Courtesy, Richard Antaya, MD; D, Courtesy, Seth Orlow, MD.

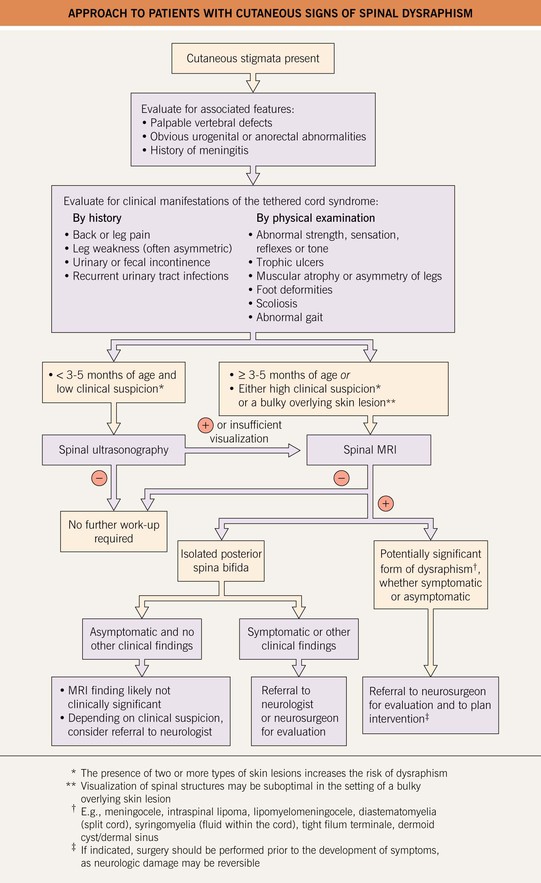

• Rx: Fig. 53.8 outlines an approach to patients with skin signs of spinal dysraphism.

Aplasia Cutis Congenita (Congenital Absence of Skin)

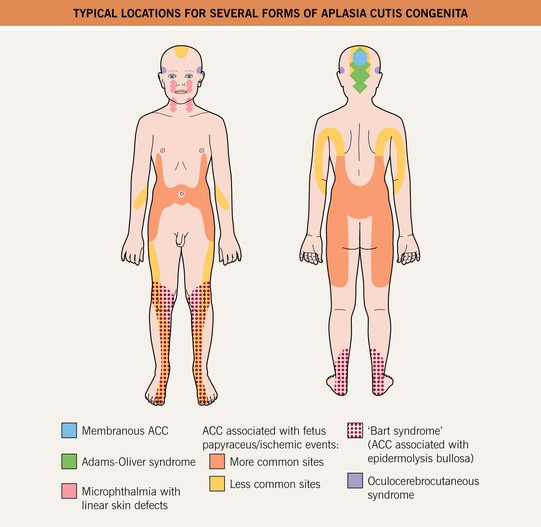

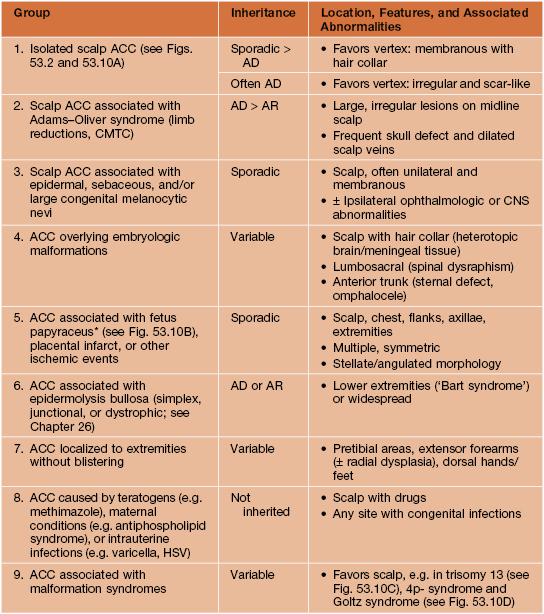

• The morphology and distribution of the skin defects (Figs. 53.9 and 53.10) and the presence or absence of associated abnormalities represent clues to the etiology of ACC (Table 53.3).

Fig. 53.9 Typical locations for several forms of aplasia cutis congenita (ACC). See Fig. 53.1 for Brauer lines/Setleis syndrome and preauricular membranous ACC. Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Fig. 53.10 Aplasia cutis congenita (ACC). A This hairless, round, scarred plaque on the scalp of a 6-month-old was present at birth. B Stellate ACC on the lateral trunk of a neonate born of an initial sextuplet gestation for which fetal reduction was performed. The lesions had a bilateral, symmetric distribution. C Stellate ACC on the midline scalp of a neonate with mosaic trisomy 13. This hemorrhagic lesion was associated with an underlying skull defect and cerebrovascular anomalies. D Membranous ACC associated with a large defect of the underlying skull in a patient with Goltz syndrome. A, Courtesy, Anthony J. Mancini, MD; B–D, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

Table 53.3

Classification scheme for aplasia cutis congenita (ACC).

* Due to second trimester death of a co-twin/triplet.

CMTC, cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita.

• The most common form is membranous ACC, which favors the scalp (especially the vertex) and presents as a sharply marginated, round to oval defect that is covered by a thin translucent membrane and often surrounded by a hair collar (see Fig. 53.2 and above); may have a bullous appearance in neonates, evolving into an atrophic scar.

• Another morphology of ACC is stellate or angulated ulcerations and scars, which may result from vascular abnormalities and/or intrauterine ischemic events (see Table 53.3).

• DDx: obstetric trauma, rudimentary meningocele (especially if bullous).

Congenital Lip and Ear Pits

• Commissural lip pits: most common form of lip pits (1–2% of newborns), found bilaterally at angles of mouth (Fig. 53.11A); usually isolated, occasionally associated with branchio-otic syndrome (preauricular pits, deafness).

Fig. 53.11 Lip and ear pits. A Bilateral commissural lip pits. B Bilateral paramedian lower lip pits, each located on the apex of a conical elevation. C Ear pit. In all of these patients, the pits represented an isolated, asymptomatic finding. B, Courtesy, Richard Antaya, MD; C, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Lower lip pits: typically bilateral at apex of conical elevation (Fig. 53.11B); isolated > associated with Van der Woude (cleft lip/palate, hypodontia) or popliteal pterygium syndrome.

• Upper lip pits: along philtrum; isolated > associated findings (e.g. hypertelorism).

• Ear pits: affect 0.5–1% of newborns, presenting as an invagination (Fig. 53.11C) > cystic nodule in the upper preauricular area (unilateral > bilateral); usually isolated (± autosomal dominant inheritance), occasionally associated with hearing impairment or malformation syndromes (e.g. branchio-oto-(±)renal syndrome, hemifacial microsomia).

Accessory Tragi (Preauricular Tags)

• Congenital anomalies of the first branchial arch that are found in ~5 per 1000 newborns.

• Soft or firm (due to a cartilaginous core) skin-colored papules or nodules covered by vellus hairs.

• Located in preauricular area > mandibular cheek (Fig. 53.12) or anterolateral neck (congenital cartilaginous rests of the neck or ‘wattles’).

Fig. 53.12 Accessory tragi. Multiple skin-colored papulonodules in a typical preauricular location as well as on the mandibular cheek.

• Rx: assessment of hearing; excision, with care to remove any cartilaginous component.

Branchial Cleft Cysts, Sinuses, and Fistulae

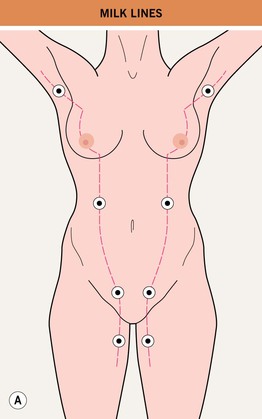

Supernumerary Nipples and Other Accessory Mammary Tissue

• Present in 2–5% of the population, representing remnants of the embryonic ‘milk lines’ (Fig. 53.13A).

Fig. 53.13 Supernumerary nipples. A Supernumerary nipples and other forms of accessory mammary tissue represent focal remnants of the embryologic mammary ridges (‘milk lines’) that extend from the anterior axillary fold to the upper medial thigh bilaterally. B Supernumerary nipple with a surrounding areola in a typical location on the inframammary chest. B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Found on the inframammary chest > axilla, vulva, or upper medial thigh.

• Small, soft, pink or brown papules, with or without a surrounding areola (Fig. 53.13B); ectopic glandular breast tissue is occasionally present (± a nipple/areola), especially in the axilla or vulva.

• Rx: excision if symptomatic or cosmetically undesirable; accessory mammary tissue can develop the same disorders as normal breasts and requires periodic breast cancer screening.

Omphalomesenteric Duct Cysts and Urachal Cysts

• Defective closure of the omphalomesenteric duct, the embryonic connection between the midgut and yolk sac, can result in an umbilical-enteric fistula, umbilical sinus or omphalomesenteric duct cyst, which typically presents as an umbilical polyp (Fig. 53.14).

Fig. 53.14 Omphalomesenteric duct cyst. The pink papule in the umbilicus of this infant showed gastrointestinal epithelium histologically. Courtesy, Mary S. Stone, MD.

• DDx: umbilical granuloma (persistent granulation tissue after cord separation).

• Rx: excision after radiographic studies to determine extent.

Rudimentary Supernumerary Digits (Rudimentary Polydactyly)

• Found in 0.5–1 : 1000 white newborns and 5–10 : 1000 black newborns.

• Soft-tissue duplications without a skeletal component, usually arising from the ulnar side of the fifth finger (postaxial location) (Fig. 53.15).

Fig. 53.15 Bilateral rudimentary supernumerary digits. The ulnar side of the fifth digit is the most common location (referred to as postaxial).

• Typically an isolated finding, often with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern.

Amniotic Band Sequence and Disorganization Syndrome

• Characterized by fibrous bands that form constriction rings and lead to amputations of limbs/digits.

For further information see Ch. 64. From Dermatology, Third Edition.