Dermatology

Victoria R. Barrio, MD, FAAD, FAAP, Kimberly D. Morel, MD, FAAD, FAAP and Lawrence F. Eichenfield, MD, FAAD, FAAP

Newborn skin is thinner, it is less hairy, it has less pigment, it has a weaker attachment of the epidermis to the dermis, and newborns may have brown fat. ∗

2. An infant is born at 29 weeks’ gestation. What are some clinical problems that may be related to immature skin barrier function in this baby?

The skin of premature infants is immature and has compromised barrier function ( Fig. 7-1). Clinical consequences include increased transepidermal water loss; fluid and electrolyte disturbances; temperature instability; infection (cutaneous and systemic); absorption of substances applied to the skin; and susceptibility to mechanical, chemical, and thermal stresses.

Figure 7-1 Premature infant skin. The skin appears very translucent, and blood vessels are readily apparent.

3. Approximately when will an infant born at 30 weeks’ gestation develop an intact barrier function?

4. Infants (especially premature infants) are at increased risk of side effects from absorption of substances from topical application (see the following Key Points box). Which topical medications can lead to methemoglobinemia if too much absorption occurs?

Prilocaine, resorcinol, aniline dyes, and methylene blue can lead to methemoglobinemia. ∗

5. Which endocrine side effect has been reported after topical application of povidone-iodine on newborn, especially preterm, skin?

Hypothyroxinemia and goiter have been reported. ∗

6. Two weeks into a neonatal intensive care unit course, an infant born at 27 weeks’ gestation develops two superficial erosions on the anterior trunk. Subsequently, these heal with a brownish, wrinkled appearance. What is the diagnosis? What is the cause?

7. What infection should be considered in a premature infant who develops pustules around a tape site (e.g., around an armboard for stabilization of an intravenous tube)?

Although bacteria, especially Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species, should always be considered as a cause of cutaneous pustules, tape sites have been associated with opportunistic fungal infections of the skin, especially involving Aspergillus species. Other fungi and yeast, including Rhizopus and Candida organisms, should also be considered. Performing a biopsy and culture is a standard approach to diagnosis. ∗

8. An infant in the newborn nursery required repeated heel sticks for blood chemistries. What possible side effect could show up after discharge, and when would you expect to see it?

Infants that receive numerous heel sticks may develop calcinosis cutis over the heel. This seldom shows up until several months after discharge. The presenting symptoms are small yellow or white papules that can be mistaken for warts. They are generally not symptomatic and will often resolve by 30 months of age. If they become problematic, they can be treated with curettage.

Subcutaneous fat necrosis may occur in cases of fetal distress, birth trauma, infection, or cold stress. It is increasingly being seen after the use of whole body cooling for the treatment of hypoxic-ischemic birth injury. ∗

Findings of sclerema usually appear in the first 2 weeks of life but can begin as late as 4 months. Infants who are poorly nourished, dehydrated, hypothermic, or septic are most commonly affected. Sclerema neonatorum begins in the lower extremities with the appearance of hard, cool skin and decreased mobility and subsequently ascends to involve the trunk and face. Palms, soles, and genitalia are usually not involved. Joints become immobile, and the face appears masklike. Sclerema may be associated with necrotizing enterocolitis, pneumonia, intracranial hemorrhage, hypoglycemia, and electrolyte disturbances. ∗

13. What is the cause of sclerema? Why is it more common in infants with infection, hypothermia, or other stressors?

Harlequin color change is a demarcated erythema forming on the dependent half of the body of newborns. In some cases the baby appears as if a line were drawn right down the midline. The more superior half of the body appears pale. This appearance can occur in any position and commonly lasts from seconds up to 20 minutes. It is rarely seen after 10 days of life. Harlequin color change is explained by immature autonomic vasomotor control because it is more common in premature infants and is reversible. If the baby is flipped over during an episode, the newly dependent portion will become erythematous.

16. Name three forms of epidermal inclusion cysts that are commonly found in neonates.

Milia: Tiny cysts, usually found on the face, occurring in up to 40% of newborns

Milia: Tiny cysts, usually found on the face, occurring in up to 40% of newborns

Epstein pearls ( Fig. 7-2): Cysts found on the palate of approximately 64% of newborns

Epstein pearls ( Fig. 7-2): Cysts found on the palate of approximately 64% of newborns

Bohn nodules: Alveolar cysts found along the lingual gum margins and the lateral palate

Bohn nodules: Alveolar cysts found along the lingual gum margins and the lateral palate

19. What is the best treatment for a small bump or hole with a hair growing in it present on the midline nose at birth?

This description fits a dermoid sinus. Midline lesions should always raise the possibility of a developmental defect. The presence of a hair coming out of the sinus is especially significant because it is considered a marker for a connection with the central nervous system. The baby should be imaged before the defect is repaired.

Preauricular skin tags, also called accessory tragi, are embryonic remnants of the first branchial arch ( Fig. 7-3). The formation of the first branchial arch occurs during the fourth week of fetal development. Because this may be associated with hearing abnormalities, patients should have their hearing screened before they are discharged from the hospital. The evidence for associated renal problems in patients with no other associated abnormalities is controversial. Renal ultrasound should be considered for patients with additional dysmorphic features or a family history of deafness or renal malformations. ∗

Accessory nipples, also called supernumerary nipples ( Fig. 7-4), are embryonic remnants of the mammary line that extend from the axilla to the inner thigh. They appear as pink or brown papules, with or without surrounding areola, anywhere along the mammary line. There have been conflicting reports about an association with urinary tract abnormalities. Current studies, however, have not found an association in patients who have no other anomalies.

Most CMNs do not have any associated complications. CMNs are often subdivided according to their size. A common classification is that a CMN greater than 20 cm in adulthood is considered to be large. Melanoma has been reported to arise within congenital lesions, but the exact risk for this complication is unclear. It is known that large lesions carry the greatest risk and that melanoma, when it occurs, does so earlier in life. Leptomeningeal melanosis is a rare complication that may occur in association with a giant congenital nevus with numerous satellite nevi. ∗

24. What are neonatal acne and transient cephalic neonatal pustulosis (TCNP)? How do these entities differ from infantile acne?

Neonatal acne usually begins at a few weeks of life and resolves over several months. Affected infants exhibit multiple inflammatory erythematous papules and pustules. Treatment is rarely needed.

Neonatal acne usually begins at a few weeks of life and resolves over several months. Affected infants exhibit multiple inflammatory erythematous papules and pustules. Treatment is rarely needed.

TCNP has been proposed as a subset of what has been called neonatal acne, which is caused by Malassezia species rather than by an elevation in androgen levels (which is present in infantile or classic acne). Others have proposed that there is no true neonatal acne and that the term TCNP (or neonatal cephalic pustulosis) should be used as a substitute. Like neonatal acne, TCNP usually begins at a few weeks of life and resolves in several months. Affected infants demonstrate multiple inflammatory erythematous papules and pustules. Comedonal lesions are rare, and treatment is rarely needed, although some experts believe that topical antiyeast agents speed resolution.

TCNP has been proposed as a subset of what has been called neonatal acne, which is caused by Malassezia species rather than by an elevation in androgen levels (which is present in infantile or classic acne). Others have proposed that there is no true neonatal acne and that the term TCNP (or neonatal cephalic pustulosis) should be used as a substitute. Like neonatal acne, TCNP usually begins at a few weeks of life and resolves in several months. Affected infants demonstrate multiple inflammatory erythematous papules and pustules. Comedonal lesions are rare, and treatment is rarely needed, although some experts believe that topical antiyeast agents speed resolution.

Infantile acne is truly an acneiform condition, with open and closed comedones as well as papules and pustules. It usually presents later, usually beyond the age of 2 to 3 months, and generally resolves between the ages of 6 and 12 months. That time sequence parallels decreases in fetal adrenal pubertal androgen levels and male testosterone levels (one possible reason males are more commonly affected). Unlike neonatal acne or TCNP, infantile acne may persist and cause scarring. For this reason, like adolescent acne, it is treated with topical antibiotics and occasionally with retinoids or systemic agents. ∗†

Infantile acne is truly an acneiform condition, with open and closed comedones as well as papules and pustules. It usually presents later, usually beyond the age of 2 to 3 months, and generally resolves between the ages of 6 and 12 months. That time sequence parallels decreases in fetal adrenal pubertal androgen levels and male testosterone levels (one possible reason males are more commonly affected). Unlike neonatal acne or TCNP, infantile acne may persist and cause scarring. For this reason, like adolescent acne, it is treated with topical antibiotics and occasionally with retinoids or systemic agents. ∗†

Erythema toxicum is a benign condition ( Fig. 7-5). Erythema toxicum is no alien to the nursery; it is present in 50% of term newborns. It is much less prevalent in premature infants, however, occurring in only approximately 5%.

Erythema toxicum usually begins between 24 and 48 hours of life and spontaneously resolves in 4 to 5 days; however, new lesions can occur up to day 10 of life. Exacerbations and remissions may occur in the first 2 weeks of life. Erythema toxicum lesions are irregularly bordered, erythematous macules, 2 to 3 cm in diameter, with central yellowish vesicopustules. They are mostly discrete, but some erythematous macules become confluent. Lesions do not involve the palms or soles.

27. Which type of cells is seen on microscopic examination of pustules scraped from erythema toxicum lesions?

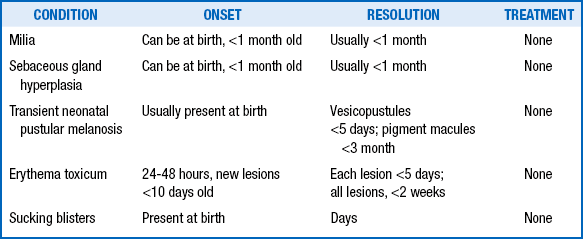

28. What is the standard treatment for milia, sebaceous gland hyperplasia ( Fig. 7-6), transient neonatal pustular melanosis, erythema toxicum, and sucking blisters?

“Nothing works.” In other words, it is not necessary to do anything other than reassure the family that the condition will resolve over time ( Table 7-1).

29. How are miliaria crystallina (also known as prickly heat) and miliaria rubra differentiated? How are they treated?

30. Why is the presence of pruritus a poor way to differentiate atopic dermatitis from seborrheic dermatitis in infants?

31. Describe the usual distribution of the rash caused by atopic dermatitis and that caused by seborrheic dermatitis in neonates.

If dermatitis involves the axillae or groin, it is more likely to be seborrheic dermatitis. If extensor surfaces such as forearms and shins are involved, atopic dermatitis is more likely. Both atopic dermatitis and seborrheic dermatitis involve scalp and posterior auricular areas, although seborrheic dermatitis has large, yellowish scale and, when severe, characteristically extends down to the forehead and eyebrow areas ( Table 7-2).

TABLE 7-2

| DISEASE | DIAPER RASH | ASSOCIATIONS |

| Candida | Bright red satellites, involves the creases | Antibiotic use, concurrent thrush |

| Irritant | Involves the exposed surfaces, spares creases, can have perianal erosions | Diarrhea, cloth diapers |

| Impetigo | Flaccid bullae and superficial erosions | Often no associations |

| Streptococcal | Tender beefy red erythema perinanal area | Often no association |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Shiny pink patches involving entire diaper area | Scalp and face involvement |

| Psoriasis | Involves entire diaper area and beyond | Often patches on the face and trunk |

| Allergic contact | Areas well demarcated to places of contact with allergen | Disposable diapers and diaper wipes |

| Zinc deficiency | Crusted eczematous involvement of entire diaper area | Irritable baby, perioral involvement, failure to thrive, can be seen in cystic fibrosis |

| Langerhans cell histiocytosis | Crusted papules or erosions, often in the creases | Crusted papules on the scalp and body |

| Hemangioma | Can present with nonhealing ulceration | Often single hemangioma; if segmental, look for associated developmental abnormalities |

| Kawasaki disease | Many presentations, but often perineal erythema with desquamation | Fever, lymphadenopathy, irritability, conjunctivitis, fissured liips |

Intertrigo literally means an erythematous rash on opposing skin surfaces or skin folds. The common causes of intertrigo include seborrheic dermatitis or infections (e.g., Candida spp.) Other infections include Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcal infections. Psoriasis, nutritional deficiency, and histiocytosis may also present as intertrigo. Clues to the diagnosis of histiocytosis include the presence of petechial or red-brown macules and papules, which are recalcitrant to topical therapy and occasionally associated with an enlarged lymph node or nodes.

This is one “clock” that does not get corrected for gestational age. Although hemangiomas are more common in preterm infants, and the female-to-male ratio is less pronounced, the chronologic age at which hemangiomas are noted to begin proliferation is the same as for full-term infants. ∗

Vascular tumors: These include the most common birthmark, the hemangioma of infancy, and other rare childhood-onset vascular tumors. The lesions are proliferating lesions composed of blood vessels. Hemangiomas have a characteristic natural history. Although not usually noticed

Vascular tumors: These include the most common birthmark, the hemangioma of infancy, and other rare childhood-onset vascular tumors. The lesions are proliferating lesions composed of blood vessels. Hemangiomas have a characteristic natural history. Although not usually noticed

Vascular malformations: These include various lesions (e.g., capillary malformations [port-wine stains], venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous, and mixed malformations). They are classified according to the type of vessels that compose them. They are often noted in the immediate newborn period. Vascular malformations grow with the child, although they may become more prominent as the child matures. They do not show a marked increase in proliferation and differ histologically from tumors. Most important, they do not regress spontaneously, and they persist throughout the patient’s lifetime. Therefore management is significantly different from that undertaken for a hemangioma.

Vascular malformations: These include various lesions (e.g., capillary malformations [port-wine stains], venous, lymphatic, arteriovenous, and mixed malformations). They are classified according to the type of vessels that compose them. They are often noted in the immediate newborn period. Vascular malformations grow with the child, although they may become more prominent as the child matures. They do not show a marked increase in proliferation and differ histologically from tumors. Most important, they do not regress spontaneously, and they persist throughout the patient’s lifetime. Therefore management is significantly different from that undertaken for a hemangioma.

Not all children with multiple skin hemangiomas have underlying systemic involvement; conversely, children with visceral hemangiomas may have no skin lesions. Children with hemangiomas located on the lower face in a “beard” pattern may have laryngeal hemangiomas that may not become detectable until they compromise breathing. Therefore a pediatric otolaryngologist should evaluate these children early in life, and early treatment is often required. ∗

Segmental hemangiomas are flatter hemangiomas that seem to involve a whole facial segment (>5 cm) or a large area on the pelvis. They are often markers of other developemental abnormalities. Large facial hemangiomas are associated with PHACE syndrome (Posterior fossa malformation, Hemangioma, Arterial abnormalities, Cardiac abnormalities, Eye abnormalities). Segmental hemangiomas that involve the sacrum and perineum can be associated with genitourinary anomalies and tethered spinal cord. ∗

Thyroid function testing should be considered. Hemangioma tissue may exhibit enzyme activity (type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase), which inactivates thyroid hormone. Laboratory testing should be performed even if the newborn screen results were within normal limits because enzyme activity can increase during the proliferative phase of the hemangioma. ∗

RICH is an acronym for a rapidly involuting congenital hemangioma.

Although smaller hemangiomas that are not problematic do not require treatment, other types do require treatment to prevent problems. Problematic hemangiomas include those that compromise vital functions, cause significant distortion or disfigurement of normal underlying structures, and have ulcerated or become infected. Treatment strategy varies depending on the clinical situation. The recent use of propranolol to treat hemangiomas has led to significant improvement in care. However, this is a relatively new indication for this medication, and considerations with its use are appropriate. ∗

Hemangiomas in this location may be associated with underlying spinal cord anomalies (e.g., a tethered spinal cord), underlying bony defects, and anomalies of the genitourinary and gastrointestinal systems. For detection of a tethered cord, magnetic resonance imaging is the study of choice. (See the following Key Points box for additional cutaneous clues to underlying spinal cord abnormalities and Fig. 7-7 for a striking example of multiple congenital anomalies overlying the midline lumbrosacral spine).

Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon (or syndrome) is a rare complication that occurs in infants with large vascular tumors. Patients usually exhibit symptoms in the first few months of life with a rapidly enlarging vascular mass associated with profound thrombocytopenia and coagulopathy. It is a life-threatening condition. In the past this phenomenon was thought to be a complication of garden-variety hemangiomas, but recent evidence indicates an association with rare vascular tumors such as kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma. ∗

A lymphangioma, also known as a lymphatic malformation, is a vascular malformation composed of lymphatic tissue. These lesions are sometimes noted in the immediate newborn period or may become more prominent as a child grows. They do not regress spontaneously. A cystic hygroma is one type of lymphatic malformation that is composed of larger cystic spaces, also called a macrocystic lymphatic malformation. It usually is apparent in the immediate newborn period and is located on the head and neck. Some patients with cystic hygroma have underlying genetic abnormalities such as Turner syndrome.

A port-wine stain is a malformation composed of small capillary and venular-size vessels. As a child matures, the lesion may darken, thicken, and develop blebs. Pulsed dye laser therapy is the preferred method of treatment and may lead to significant lightening in many patients. Multiple treatments are usually required. These lesions differ from the “stork bite” and “angel kiss” nevus simplex, which do not progress and do not need to be treated. ∗

53. When should Sturge–Weber syndrome be considered in a child with facial port-wine stain? What are the characteristic findings in Sturge–Weber syndrome?

54. What are the modes of inheritance of neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2? What protein mutations are involved in these genetic diseases?

Both diseases are autosomal dominant, but spontaneous mutations account for approximately half of cases. The incidence of neurofibromatosis type 1 is 1 in 2500; the mutated gene product is neurofibromin, a protein involved in tumor suppression. Neurofibromatosis type 2 has a reported incidence of 1 in 33,000; the involved gene product is merlin, which mediates cytoskeleton and extracellular movement. ∗

58. Tuberous sclerosis is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion. What is peculiar about the genetic abnormalities associated with the tuberous sclerosis phenotype?

Two distinct chromosomal complexes on two different chromosomes are implicated as areas of mutation that result in tuberous sclerosis. Tuberous sclerosis complex 1 results from mutations in the gene hamartin on chromosome 9, located at 9q34.3. Tuberous sclerosis complex 2 is caused by mutations in the tuberin gene on chromosome 16 at 16p13.3.

Of newborns with collodion membrane, the most common ichthyosis that develops is nonbullous ichthyosiform erythroderma, also called congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma. Lamellar ichthyosis is another rare form of ichthyosis that may present initially with collodion membrane. Both are classified as autosomal recessive congenital ichthyoses. Approximately 5% of babies with collodion membrane do not go on to have clinically significant skin disease. Furthermore, not all patients with ichthyotic skin disease have a collodion membrane at birth. ∗

The X-linked ichthyosis steroid sulfatase deficiency is associated with failure to progress during labor. Mothers have difficulty with cervical dilation and fail to adequately respond to intravenous oxytocin often necessitating a forceps delivery or cesearean section.

Epidermolysis bullosa is a heterogeneous group of inherited disorders characterized by skin fragility and blistering ( Fig. 7-8). Most patients develop symptoms in the newborn period. The most common types are epidermolysis bullosa simplex, junctional epidermolysis bullosa, and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa. Within each subset there are different clinical phenotypes. It is now understood that these diseases are caused by an inability to synthesize proteins that play an important role in maintaining the skin’s integrity. Epidermolysis bullosa simplex is caused by mutations in keratins located in the basal layer of the epidermis; junctional epidermolysis bullosa is caused by defects in the protein laminin 5 and other proteins at the dermal–epidermal junction, and dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa is caused by a defect in collagen VII. There is no cure for these conditions, and treatment is supportive, although trials of bone marrow transplant and gene transfer are ongoing.∗

Skin trauma (e.g., rubbing, chafing) is strongly discouraged, because the skin will likely blister or erode at the site. Tape should not be applied directly to the skin. New blisters should be ruptured with a sterile needle or lancet (to prevent them from enlarging), with the blister roof left in place, and dressed with a topical antibiotic and nonadherent dressing (e.g., plain petrolatum and gauze). The blisters should be monitored closely because superinfection may be a complication. Infants with severe forms of epidermolysis bullosa are at risk for nutritional deficiencies, poor weight gain, and anemia.

∗Eichenfield LF, Frieden IJ, Esterly NB. Textbook of neonatal dermatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008.

∗Mohorovic L, Materljan E, Brumini G. Consequences of methemoglobinemia in pregnancy in newborns, children, and adults: issues raised by new findings on methemoglobin catabolism. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2010;23:956–9.

∗Mancini AJ. Skin. Pediatrics 2004;113:1114–1119.

∗Smolinski KN, Shah SS, Honig PJ, et al. Neonatal cutaneous fungal infections. Curr Opin Pediatr 2005;17(4):486–93.

∗Zifman E, Mouler M, Eliakim A, et al. Subcutaneous fat necrosis and hypercalcemia following therapeutic hypothermia—a patient report and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab 2010;23(11):1185–8.

∗Zeb A, Darmstadt GL. Sclerema neonatorum: a review of nomenclature, clinical presentation, histological features, differential diagnoses and management. J Perinatol 2008;28:453–60.

∗Roth DA, Hildesheimer M, Bardenstein S, et al. Preauricular skin tags and ear pits are associated with permanent hearing impairment in newborns. Pediatrics 2008;122(4):e884–90.

∗Slutsky JB, Barr JM, Femia AN, et al. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: associated risks and management considerations. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2010;29(2):79–84.

∗Niamba P, Weill FX, Sarlangue J, et al. Is neonatal cephalic pustulosis (neonatal acne) triggered by Malassezia sympodialis? Arch Dermatol 1998;134:995–998.

†Friedlander SF, Baldwin HE, Mancini AJ, et al. The acne continuum: an age-based approach to therapy. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2011;30:S6–11.

∗Garzon MC, Drolet BA, Baselga E, et al. Comparison of infantile hemangiomas in preterm and term infants: a prospective study. Arch Dermatol 2008;144(9):1231–2.

∗Drolet BA, Chamlin SL, Garzon MC, et al. Prospective study of spinal anomalies in children with infantile hemangiomas of the lumbosacral skin. J Pediatr 2010;157(5):789–94.

∗Metry D, Heyer G, Hess C, et al. Consensus statement on diagnostic criteria for PHACE syndrome. Pediatrics 2009;124(5):1447–56.

∗Huang SA, Tu HM, Harney JW, et al. Severe hypothyroidism caused by type 3 iodothyronine deiodinase in infantile hemangiomas. N Engl J Med 2000;343:185–189.

∗Leaute-Labreze C, Dumas de la Roque E, Hubiche T, et al. Propranolol for severe hemangiomas of infancy. N Engl J Med 2008;358(24):2649–51.

∗Kelly M. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon. Pediatr Clin North Am 2010;57:1085–9.

∗Bencini PL, Tourlaki A, De Giorgi V, et al. Laser use for cutaneous vascular alterations of cosmetic interest. Dermatol Ther 2012;25:340–51.

∗Williams VC, Lucas J, Babcock MA, et al. Neurofibromatosis type 1 revisited. Pediatrics. 2009;123:124–33.

∗Oji V, Tadini G, Akiyama M, et al. Revised nomenclature and classification of inherited ichthyoses: results of the First Ichthyosis Consensus Conference in Sorèze 2009. J Am Acad Dermatol 2010;63:607–41.

∗Fine JD, Eady RA, Bauer EA, et al. The classification of inherited epidermolysis bullosa (EB): Report of the Third International Concensus Meeting on Diagnosis and Classification of EB. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58(6):931–50.