98 Demyelinating Disorders

• Monocular vision loss from optic neuritis is a characteristic manifestation of multiple sclerosis (MS).

• Elevated body temperature worsens the symptoms of MS.

• Treatment of MS typically requires steroids to decrease autoimmune, inflammatory myelin damage.

• Transverse myelitis usually causes flaccid paraparesis initially, but it becomes spastic later.

• Back pain may precede neurologic symptoms in patients with MS and Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

• Patients with GBS can initially have paresthesias followed by ascending weakness.

• Respiratory evaluation of forced vital capacity should be performed in patients with GBS.

• Succinylcholine should be avoided in patients with GBS because it can cause hyperkalemia.

• Treatment of acute optic neuritis requires admission for intravenous steroids.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Multiple Sclerosis

Ocular findings are the most common initial symptom. Optic neuritis is manifested as subacute monocular vision loss, although it can affect both eyes, and pain exacerbated with eye movement. It is the initial symptom in 25% and ultimately affects 50% of patients.1 The course usually progresses over a period of 2 weeks and may be include headache, retroorbital or periocular pain, and alterations in color vision and visual fields. Slit-lamp examination may demonstrate cell and flare in the anterior chamber. The optic disk is frequently swollen on initial evaluation. In addition to optic neuritis, the patient may have an afferent pupillary defect (Marcus Gunn pupil, or decreased pupillary constriction on direct light confrontation but a normal consensual response) or intranuclear ophthalmoplegia, which is characterized by dysconjugate gaze with limited adduction of one eye and nystagmus in the abducting eye on lateral gaze as a result of a lesion involving the medial longitudinal fasciculus.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

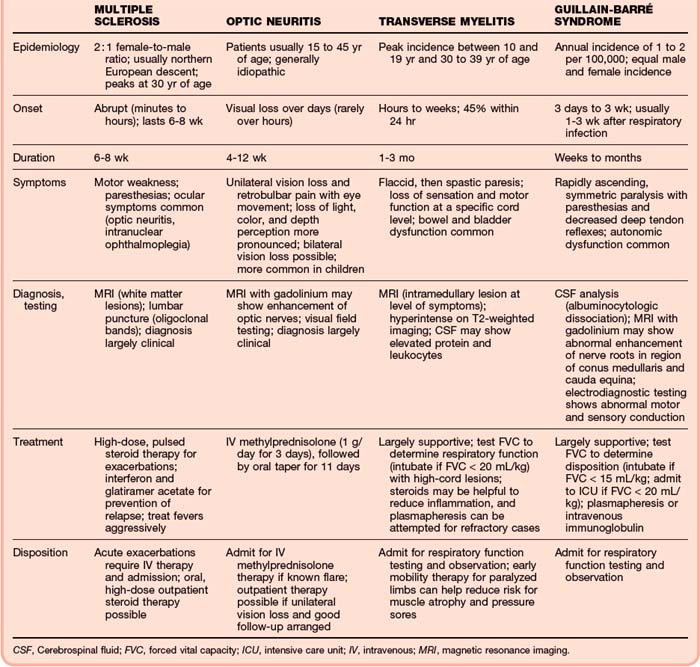

Clinical factors that suggest a diagnosis other than MS (Table 98.1) include normal findings on neurologic examination, aphasia, predominance of pain, abrupt hemiparesis, quick (seconds or minutes) resolution of symptoms, and age younger than 10 or older than 50 years.

| DISEASE/SYSTEM | IMPORTANT FACTORS |

|---|---|

| Seizures, syncope, or dementia | Present diffusely or globally; MS is usually focal; consider Todd paralysis in seizure patients |

| SLE | Neurologic findings normally occur in patient with a known diagnosis of SLE |

| Sarcoid | CNS and pulmonary involvement normally occurs in patients with known disease |

| Lyme disease | Can mimic MS; look for tick exposure, travel history, and Lyme disease titers |

| CNS infection | Intracranial abscess, meningitis/encephalitis, or epidural abscess can produce focal findings |

| Bleeding (CNS) | Subdural, subarachnoid, intraparenchymal, or epidural hemorrhage can produce focal findings |

| Neoplasm | Usually progressive course with a more insidious onset |

| Vascular | Patients with thrombosis, embolism, or vasculitic conditions do not usually have resolution of symptoms |

| Metabolic | Vitamin B12 deficiency, hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia (hyperosmolar) |

| Neurologic | Migraine headache, postictal state, Bell palsy |

| Psychiatric | Diagnosis of exclusion; includes conversion reaction |

CNS, Central nervous system; MS, multiple sclerosis; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus.

The EP should consider the diagnosis in a young adult with a history of two or more clinically distinct episodes of central nervous system dysfunction or the presence of highly suggestive symptoms (optic neuritis or intranuclear ophthalmoplegia). In 2005, the McDonald criteria revised the 2001 guidelines of the International Panel on MS2 to incorporate specific MRI findings and reaffirm the need for separation of clinical events and lesions in space and time. Diagnostic confidence is based on whether the criteria are fully met (diagnosis of MS), partially met (possible MS), or not met (not MS). Table 98.2 lists characteristic factors differentiating demyelinating disorders.

Diagnostic Testing

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI is extremely useful for confirming the presence of an intramedullary lesion at the level in the spinal cord commensurate with the symptoms of transverse myelitis. The lesions are typically hyperintense on T2-weighted imaging; they involve the majority of the cross-sectional area of the cord over several segments and may be enhanced with contrast agents. The lesions may cause swelling of the spinal cord. Gadolinium-enhanced MRI may show abnormal enhancement of the nerve roots in the region of the conus medullaris and cauda equina.3

Treatment

Multiple Sclerosis

Treatment of MS can be discussed in terms of the management of acute relapses, prevention of relapses as a modification of the disease process, and management of symptoms and fixed neurologic deficits. High-dose pulsed corticosteroid therapy is indicated for exacerbations of acute relapses that adversely affect the patient’s function. Intravenous (IV) methylprednisolone at doses of 0.5 to 1 g daily for 5 days reduces the maximal neurologic signs and hastens the resolution of associated fatigue. A controversial study by Sellebjerg et al. supports the use of oral methylprednisolone (500 mg daily for 5 days with a 10-day tapering period).4

In patients with relapsing-remitting MS, disease-modulating drugs reduce the frequency of attacks, the rate of increase in lesions seen on MRI, and the accumulation of disability. In patients with relapsing disease of mild to moderate severity, interferon beta-1b, given subcutaneously every other day, reduced the year-on-year relapse rate by one third and severe attacks by one half. The effect was maintained for up to 5 years.5,6 In another study, interferon β1b reduced MRI contrast-enhanced lesions by 1.6%, as opposed to a 15% increase in those receiving placebo. The number of enlarging or new lesions was also significantly reduced.7 Antibodies developed in 35% of patients taking interferon β1b, but there is a lack of consistent effect of antibodies on clinical outcome. Additionally, these antibody levels were found to have disappeared in the majority of patients after 8 years of treatment.8,9

Interferon β1a produced similar benefits when given intramuscularly three times per week, with a 17% reduction in the relapse rate. When compared with weekly, low-dose interferon β1a, high-dose interferon β1a given three times per week demonstrated a 32% relative reduction in steroid use to treat relapses.10

Glatiramer, a synthetic random compound composed of four amino acids, is found in myelin. Its exact mechanism is unknown, but it is believed that glatiramer acetate binds to the major histocompatibility complex class II antigen and induces organ-specific T helper type 2 cell responses, thus converting proinflammatory T cells to antiinflammatory agents.11 Treatment with glatiramer reduces the relapse rate by 30% and may delay disease progression.12

Natalizumab, a monoclonal antibody against α4 integrins, is effective for relapsing-remitting MS. The reduction in annualized relapse rates with natalizumab is similar to that with glatiramer or interferon β.13 However, it is not a first-line agent because it can cause progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in 0.1% of cases.14

Fingolimod, the first oral treatment option for MS approved by the Food and Drug Administration, is a sphingosine analogue that blocks lymphocyte release from lymph nodes through interaction with the sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor. Fingolimod can significantly reduce relapse rates when compared with interferon β1a. However, fingolimod is associated with life-threatening infections, bradycardia, atrioventricular block, tumor development, and macular edema.15

Specific therapies for relief of symptoms are provided in Table 98.3.

| SYMPTOM | TREATMENT OPTIONS |

|---|---|

| Fatigue | Amantadine, pemoline, methylphenidate, modafinil, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

| Weakness | Steroids, potassium channel blocker |

| Loss of balance or coordination, tremor, ataxia | Clonazepam for tremor, steroids for balance |

| Sexual dysfunction | Sildenafil, intracavernosal prostaglandins (for erectile dysfunction) |

| Vertigo | Meclizine, prochlorperazine, diazepam, metoclopramide |

| Paroxysmal symptoms (itching, burning, twitching, Lhermitte sign) | Carbamazepine, phenytoin, tricyclic antidepressants, low-dose antipsychotics, gabapentin |

| Bladder urgency | Oxybutynin, tolterodine, imipramine, hyoscyamine, propantheline |

| Bladder dyssynergia | Phenoxybenzamine, clonidine, terazosin |

| Bladder retention | Intermittent catheterization, bethanechol |

| Spasticity (commonly increased tone in the lower extremities) | Baclofen, diazepam, tizanidine, clonazepam, clonidine (adjunctive to baclofen), dantrolene |

| Paresthesias | Amitriptyline, carbamazepine, gabapentin, corticosteroids if disabling |

| Optic atrophy, blurred vision, central scotomata | Intravenous methylprednisolone for acute optic neuritis |

| Intranuclear ophthalmoplegia | Corticosteroids |

| Ataxia | Clonazepam, gabapentin |

| Paroxysmal pain | Carbamazepine, phenytoin, misoprostol (trigeminal neuralgia) |

| Dysesthetic pain | Amitriptyline, phenytoin, gabapentin, valproic acid, carbamazepine, baclofen |

Transverse Myelitis

Corticosteroids and plasma exchange may be beneficial in the treatment of transverse myelitis.16 In a small case series, patients treated with steroids were able to walk after a median time of 23 days versus 97 days for historical controls.17 Plasma exchange is often used for those with more severe disease (e.g., unable to walk) who fail to improve with IV steroid therapy.18 The prognosis for transverse myelitis is variable.

Optic Neuritis

IV methylprednisolone (1 g/day for 3 days) followed by oral prednisone (1 mg/kg/day for 11 days with a 4-day taper) and interferon β1a (30 mcg intramuscularly once a week) for patients at high risk for MS based on MRI has been shown to hasten recovery of vision in patients with optic neuritis.19 However, this therapy shows little residual benefit at 1 year. Additionally, oral prednisone therapy alone was found to actually increase the recurrence rate.20 Regardless of therapy, most patients recover their vision within a month.

Follow-up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

The National Multiple Sclerosis Society (http://www.nmss.org), Guillain-Barré Foundation (http://www.gbsfi.com/), and Transverse Myelitis Foundation (http://www.myelitis.org/) provide excellent patient resources and offer support groups for both patients and family.

Patients are at risk for exacerbation of symptoms and progression of disease from an elevated core temperature. Aggressive fever control and determination of its cause are important.

There is no cure for demyelinating disorders, but current therapies can reduce their frequency and severity.

Patients with optic neuritis have a worse prognosis with oral steroid therapy. If steroids are used, they must be given intravenously.

Patients with symptoms of progressive weakness and sensory symptoms must be assessed rapidly for Guillain-Barré syndrome. With aggressive therapy, respiratory failure can be avoided.

Balcer LJ. Clinical practice. Optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1273–1280.

Panitch H, Goodin D, Francis G, et al. EVIDENCE (Evidence of Interferon Dose-response: European North American Comparative Efficacy) Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Research Group. Benefits of high-dose, high-frequency interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis are sustained to 16 months: final comparative results of the EVIDENCE trial. J Neurol Sci. 2005;239:67–74.

Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846.

Ropper AG. Selective treatment of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:965–967.

1 Balcer LJ. Clinical practice. Optic neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1273–1280.

2 Polman CH, Reingold SC, Edan G, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2005 revisions to the “McDonald criteria.”. Ann Neurol. 2005;58:840–846.

3 Patel H, Garg BP, Edwards MK. MRI of Guillain-Barré syndrome. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1993;17:651–652.

4 Sellebjerg F, Frederiksen JL, Nielsen PM, et al. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of oral, high-dose methylprednisolone in attacks of MS. Neurology. 1998;51:529–534.

5 Interferon beta-1b in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: final outcome of the randomized controlled trial. IFNB Multiple Sclerosis Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Analysis Group. Neurology. 1995;45:1277–1285.

6 Arnason BG. Long-term experience with interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2005;252(Suppl 3):iii28–iii33.

7 Miller DH, Molyneux PD, Barker GJ, et al. Effect of interferon 1-b on magnetic resonance imaging outcomes in secondary progressive multiple sclerosis: results of a European multi-center, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. European Study Group on Interferon-beta 1b in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:850–859.

8 Polman C, Kappos L, White R, et al. European Study Group in Interferon Beta-1b in Secondary Progressive MS. Neutralizing antibodies during treatment of secondary progressive MS with interferon beta-1b. Neurology. 2003;60:37–43.

9 Rice GP, Paszner B, Oger J, et al. The evolution of neutralizing antibodies in multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta 1-b. Neurology. 1999;52:1277–1279.

10 Panitch H, Goodin D, Francis G, et al. EVIDENCE (Evidence of Interferon Dose-response: European North American Comparative Efficacy) Study Group and the University of British Columbia MS/MRI Research Group. Benefits of high-dose, high-frequency interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis are sustained to 16 months: final comparative results of the EVIDENCE trial. J Neurol Sci. 2005;239:67–74.

11 Arnon R, Aharoni R. Mechanism of action of glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis and its potential for the development of new applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14593–14598.

12 Johnson KP, Brooks BR, Cohen JA, et al. Copolymer 1 reduces relapse rate and improves disability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: results of a phase III multicenter, double-blind placebo-controlled trial. The Copolymer 1 Multiple Sclerosis Study Group. Neurology. 1995;45:1268–1276.

13 Ropper AG. Selective treatment of multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:965–967.

14 Yousry TA, Major EO, Ryschkewitsch C, et al. Evaluation of patients treated with natalizumab for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:924–933.

15 Cohen JA, Barkhof F, Comi G, et al. Oral fingolimod or intramuscular interferon for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:402–415.

16 Krishnan C, Kaplin A, Deshpande D, et al. Transverse myelitis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1483–1499.

17 Kennedy PG, Weir AI. Rapid recovery of acute transverse myelitis treated with steroids. Postgrad Med J. 1988;64:384–385.

18 Weinshenker BG. Plasma exchange for severe attacks of inflammatory demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system. J Clin Apher. 2001;16:39–42.

19 Balcer LJ, Galetta SL. Treatment of acute demyelinating optic neuritis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2002;17:4–10.

20 Visual function 5 years after optic neuritis: experience of the Optic Neuritis Treatment Trial. The Optic Neuritis Study Group. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115:1545–1552.