10 Day surgery

Introduction

Summary Box 10.1 Clinical effectiveness of day surgery

• The surgical outcomes of a procedure performed on a day case basis or as an inpatient should, in theory, be identical, as it is the patient pathway and not the surgery that is different

• In practice, surgical outcomes from patients undergoing day surgery rather than inpatient surgery are often better as day surgery patients are a preselected cohort of healthier patients with fewer comorbidities.

Facilities for day surgery

Hospital integrated units

Summary Box 10.2 Cost effectiveness of day surgery

• Same-day admission and discharge avoids the costs of an overnight inpatient bed

• Criteria based pre-assessment reduce unnecessary investigations

• Dedicated day or ambulatory theatre lists maximize surgical throughput

• Protocol-based discharge with comprehensive patient information reduces unplanned hospital readmissions.

The patient pathway

First patient contact

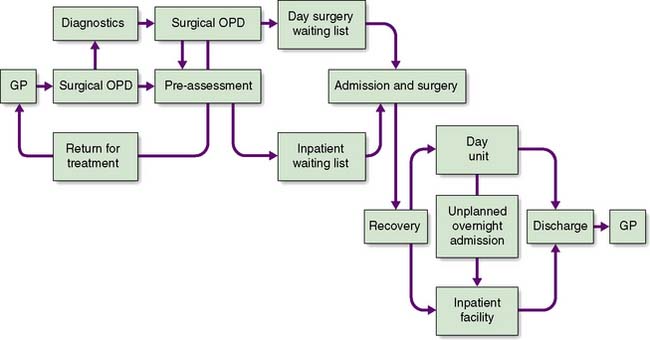

An efficient and effective ambulatory pathway (Fig. 10.1) requires the patient to arrive at the day unit on the day of surgery fully prepared for their procedure both physically and mentally. Preparation for possible day surgery starts at first patient contact with their General Practitioner. Patients will often raise the topic of day surgery themselves as their preferred management option at their initial consultation. A brief ‘health screen’ with the GP referral letter detailing the patient’s blood pressure, body mass index, medication and past medical history allows the surgeon at out-patients to consider appropriate pre-assessment required for the patient. If no diagnostic or other investigations are required, the patient can be listed for their surgical procedure and referred immediately for pre-assessment, avoiding a follow-up out-patient clinic appointment.

ASA status

This is used to assess the physical state of the patient prior to surgery and has been adopted worldwide (Table 10.1). Most day units accept ASA I and II patients. More advanced units and those that can deal safely with unplanned overnight admissions may accept some patients with ASA III status such as insulin-dependent diabetics.

Table 10.1 American Society of Anaesthesiologists classification of physical status

| ASA I | Normal healthy patients. Little or no risk for surgery. |

| ASA II | Patients with mild systemic disease. Minimal risk during treatment. Examples include well-controlled non-insulin dependent diabetes, mild hypertension, epilepsy or asthma. |

| ASA III | Patients with severe systemic disease that limits activity but is not incapacitating. These patients need medical input before surgery. Examples include insulin-dependent diabetes or a history of myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure or cerebrovascular accident in the preceding six months. |

| ASA IV | Patients with severe systemic disease limiting activity and is a constant threat to life. Elective surgery is contradicted and emergency surgery requires urgent medical input. Examples include unstable diabetes, hypertension and epilepsy or a recent myocardial infarction. |

| ASA V | Patients who are moribund and not expected to survive more than 24 hours without an operation |

Pre-assessment

Pre-assessment is offered to the patient in a number of options:

1. At source in the GP surgery. This model is used in surgical outreach clinics when the pre-assessment nurse accompanies the surgeon to the clinic. It is more cost effective however to train a practice nurse to perform the routine pre-assessments and refer more complex patients for hospital pre-assessment.

2. At the pre-assessment clinic. Formal pre-assessment consultations can be programmed in advance for 30–60 minute interviews depending on the complexity of the patient.

3. At the surgical outpatient clinic. Where a number of surgical clinics are running concurrently, it is cost effective to offer patients a ‘one-stop’ pre-assessment service. Patients requiring more complex pre-assessment can be deferred to a planned pre-assessment clinic at a later date.

4. By telephone, postal questionnaire or internet (e-mail or on-line). This model is suitable for fit patients undergoing straightforward procedures especially if they have already had a basic health screen performed at the GP surgery.

Medication

Warfarin

• Atrial fibrillation (AF): Anticoagulation with warfarin reduces the annual embolic stroke rate from 4% to 2%. Stopping warfarin one week prior to surgery to normalize coagulation poses little risk of stroke.

• VTE: After DVT or PE patients are usually anticoagulated for 3–6 months. Ideally, surgery should be deferred until the course of anticoagulation has ceased. If this is not possible then conversion to heparin therapy preoperatively is advocated.

• Prosthetic heart valves: Mitral valves are intolerant of normal coagulation and conversion to heparin therapy is required, thereby excluding such patients from day surgery. Aortic valves are less susceptible to embolization due to high blood flows and closing pressures and warfarin can be safely stopped 3 days before surgery and restarted immediately after operation.

Past medical history

Diabetes

The three key principles in managing the diabetic patient as a day case are:

Investigations

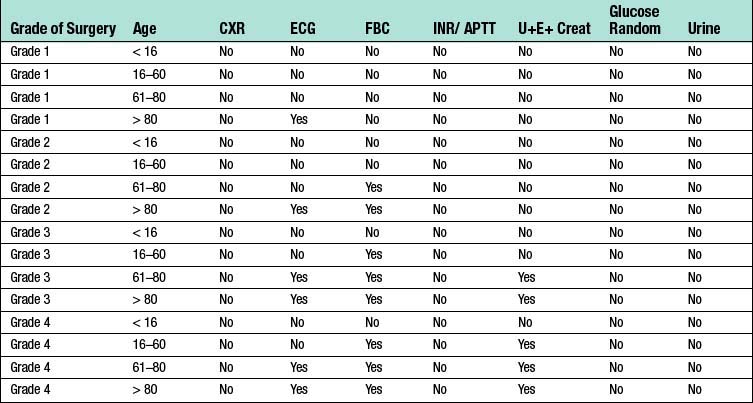

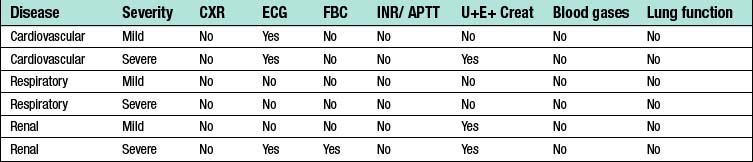

Many preoperative assessment clinics take blood and record 12-lead electrocardiograms for their patients but this is not evidence-based. NICE (National Institute for Clinical Evidence) conducted an extensive systematic review of routine preoperative tests and concluded that the evidence for investigations did not exist. The NICE guidelines are therefore based on the consensus opinion of healthcare professionals and relate to the grade of surgery being performed (Table 10.2), the patient’s age (Table 10.3), and the severity of any underlying disease, whether cardiovascular, respiratory or renal (Table 10.4).

Table 10.2 Grade of surgery related to NICE preoperative investigations

| Grade 1 | Diagnostic laparoscopy or endoscopy, breast biopsy |

| Grade 2 | Inguinal hernia, varicose veins, knee arthroscopy, tonsillectomy |

| Grade 3 | Thyroidectomy, abdominal hysterectomy, TURP |

| Grade 4 | Colonic resection, joint replacement, artery reconstruction |

A sickle cell test is required for:

• patients of African or Afro-Caribbean descent

• patients with a family history of homozygous sickle cell disease or heterozygous trait

• patients from the Eastern Mediterranean, Middle East and Asia.

Summary Box 10.3 Pre-assessment

• All elective surgical patients should be pre-assessed

• All patients undergoing a procedure suitable for day surgery should initially be defaulted to day surgery, and only if not clinically fit should they be allocated to an overnight stay

• The pre-assessment team should be empowered to allocate the appropriate length of stay to each individual patient

• Pre-assessment should be performed early in the patient pathway to avoid late cancellation for surgery. This can occur if the patient is found to be unfit for day surgery, with insufficient time to optimize their health.

Admission for surgery

An efficient and effective ambulatory pathway requires the patient to arrive at the day unit on the day of surgery fully prepared for their procedure both physically and mentally (Fig. 10.2). Admission administration is minimal. Patients can sign their consent form to confirm they wish to proceed with their operation at any appropriate point before their procedure. If the patient signs the form in advance, a health professional involved in their care on the day should also sign it to confirm the patient still wishes to proceed. The diagnosis and planned surgery should be confirmed as still appropriate and the operation site marked. Although consent remains valid indefinitely unless withdrawn by the patient, many hospitals time-limit consent forms to 3 months after dating on safety grounds.

Recovery

• First stage – until the patient is awake after anaesthesia

• Second stage – until the patient is discharged from hospital

• Late – until the patient has returned to normal activities.

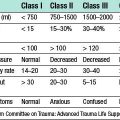

The management of PONV can be divided into general measures given to all patients and specific medication given to those at higher risk (Table 10.5). General measures include the use of short-acting anaesthetics, pre-emptive non-opioid analgesia and a reduction in the fluid deficit by minimizing the preoperative fast and giving IV fluids peroperatively. Patients at risk for PONV may require the routine administration of a 5HT3 antagonist such as ondansetron or granisetron; if at very high risk, dexamethasone 4–8 mg may be given in addition.

| Key risk factors | Additional surgical risk factors |

|---|---|

| Female gender | Oral or ENT surgery |

| Non-smoker | Squint surgery |

| Previous history of PONV | Laparoscopic surgery |

| Suffers motion sickness | |

| Perioperative use of opioids |

Discharge criteria

The decision as to when a patient is fit for discharge from the day unit should be taken by trained nursing staff using agreed discharge criteria protocols (Table 10.6). A postoperative visit by the surgeon and anaesthetist is encouraged at the end of the operating list, but awaiting a member of the busy surgical team to discharge the patient usually results in delay.

• wound care dressing renewal and suture removal (if required)

• return to normal activities including work, sexual activities and exercise

• signs and symptoms which may indicate a problem

• contact emergency telephone number and follow-up arrangements

Day surgery procedures

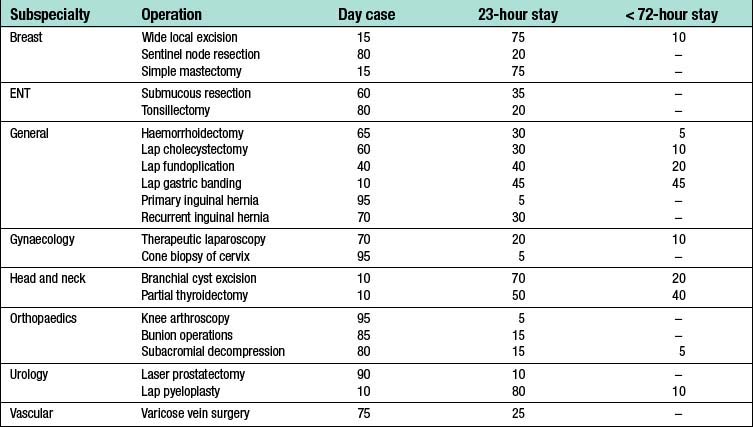

The rapid expansion of minimal access techniques in surgery over the last 20 years has offered many possibilities for converting a surgical procedure from an in-patient to a day case. Anaesthesia and analgesia have markedly improved and procedures up to 2 hours long can even be performed on a day case basis provided they are scheduled early in the day. For many years the Audit Commission ‘Basket of 25’ surgical procedures provided a template for day surgery (Table 10.7). However, as most of these procedures are minor or intermediate in nature (accounting for only about 25% of all day surgery) and several others are now obsolete, the ‘Basket’ is now of limited value. There is also a realization that reducing the length of stay of the short stay surgical pathway for each patient by one day provides a similar reduction in overnight bed days as converting a patient from a 23-hour stay to a day case. The British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) directory of procedures offers information on over 200 day and short stay surgical procedures indicating the percentage of a particular procedure which could be performed as a day case, as an overnight 23-hour stay or a short stay admission up to 72 hours given ideal theatre and organizational conditions. A selection of these aspirational percentages for common day and short stay surgical procedures is shown in Table 10.8.