CHAPTER 20 Data collection

Introduction

In the developed world there is a ‘Quality Chasm’ between the quality of care that can be achieved and the quality and consistency of care that is being delivered. Several types of quality problems have been documented including, undue variation within services, underuse of services, overuse of services, misuse of services, and regional or ethnic disparities. Health care’s problems with safety and quality are often because it relies on outdated systems of work. Only by re-designing systems of care including the use of information technology and automated decision support will consistently improved quality of care be delivered. Both in the United States of America (USA)1 and in the United Kingdom (UK)2 major reports have highlighted these problems and charted a route to higher quality health care in the future.

Cataract surgery – how should data be collected?

Alternatives to EMR systems for aggregating clinical process and outcomes data are national or international registries. Sweden led the way with an active National Cataract Register that has been able to identify changing trends since 19923. Initially data were submitted on paper proformas but web-based data entry is now the norm. The European Society of Cataract and Refractive Surgery has recently been funded to establish a pan-European registry with web-based data entry4. Whilst registries are welcome there are limited mechanisms to guarantee the accuracy of data or to determine what cases have been omitted. The work involved in entering data into a web-based registry is always additional to the work involved in hand writing the paper notes or entering data into local EMR systems, which limits the volume and detail of data that can be collected.

Cataract surgery – what data should be collected?

The UK has had a formal national process involving all relevant stakeholders to define the ‘Cataract National Dataset’ (CND)5. When this is ratified it will be a standard to which all EMR suppliers to the UK National Health Service (NHS) must conform. The UK CND represents the most detailed definition of data collection for cataract surgery in the world and numerous peer reviewed publications have demonstrated that it is fit for purpose in allowing detailed audit of the process and outcome of care as a by-product of routine clinical care6–8. Almost a third of the 300 000 cataract operations performed per annum in the NHS in England are now recorded within EMR systems from the same supplier, but each hospital has a separate instance of the program. To date there has been no automatic mechanism for aggregating pseudoanonymized data from all sites but a National Ophthalmology Database is being established for this purpose.

Cataract surgery – how should the data be used?

Clinician self-improvement

Clinicians will be interested in automated risk analysis and decision support that improves clinical decision making for their patients. For example EMR systems allow clinicians to accurately quantify the risk of posterior capsular rupture in eyes with multiple risk factors for different grades of surgeon6 and can automatically calculate customized ‘A’ constants for IOL calculation formulae, which substantially improves the predictability of the refractive outcomes of cataract surgery.

Accreditation, regulation, and revalidation

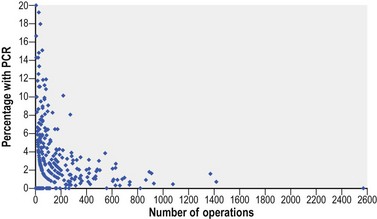

In some health economies clinicians are required by regulators to audit their clinical outcomes and demonstrate their continued fitness to practice. Numerous clinical studies document ‘mean’ outcomes, but very few studies analyse variations in clinical outcomes between surgeons or institutions, whilst taking due account of case mix. This is necessary if acceptable boundaries of performance are to be scientifically defined without the risk of making surgeons averse to operating on complex cases. Posterior capsular rupture rates between surgeons of different grades have been published for a dataset of 55 567 cataract operations7 (Fig. 20.1) and future publications will adjust each surgeon’s rate according to their case mix complexity using a statistical process control chart (or funnel plot) to identify outliers.

Purchasers

Purchasers of health care have a legitimate interest in ensuring there is no ‘overuse’ or ‘under-provision’ of cataract surgery. In New Zealand and in some parts of the UK there have been examples of access to cataract surgery being crudely limited according to levels of preoperative visual acuity, which is known to be an insufficiently sensitive measure of need. Purchasers of health care and professional bodies have in the past relied on crude proxy measures of quality such as length of stay or frequency of return to theater within 28 days, but are now attempting to identify more specific indicators to drive quality improvement in clinical processes and outcomes (for example, percentage of eyes without co-pathology achieving 20/40 or better visual acuity postoperatively; percentage of eyes having a defined comprehensive preoperative assessment, percentage of eyes having an anterior vitrectomy at the time of cataract surgery). The National Quality Measures Clearinghouse website provides information on specific evidence-based health care quality measures and currently has ten measures related to cataract surgery9.

Epidemiological research

As very clearly articulated by Dr JC Javitt in an editorial titled ‘Rule Britannia’10, EMR systems open many opportunities for reliable epidemiological research at low cost. True ‘outcome studies’ are now possible where EMR data are collected from a ‘sufficiently broad sample of the population as to be representative of the results typically obtained in community practice’. This is achieved because data collected for routine clinical practice and for clinical research are one and the same.

1 Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine, National Academy Press; 2001.

2 Professor the Lord Darzi of Denham KBE. High quality care for all: NHS Next Stage Review final report. Edinburgh: TSO; 2008.

3 Available from www.cataractreg.com/index.htm

4 Available from www.eurequo.org

5 Available from www.rcophth.ac.uk/about/college/doas-cataract

6 Narendran N, Jaycock P, Johnston RL, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55 567 operations: risk stratification for posterior capsule rupture and vitreous loss. Eye. 2008;23:31-37.

7 Johnston RL, Taylor H, Smith R, et al. The Cataract National Dataset Electronic Multi-centre Audit of 55 567 Operations: variation in posterior capsule rupture rates between surgeons. Eye (Lond). 2010;24(5):888-893.

8 Benzimra JD, Johnston RL, Jaycock P, et al. The Cataract National Dataset electronic multicentre audit of 55 567 operations: antiplatelet and anticoagulant medications. Eye. 2008;23:10-16.

9 Available from www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/search/searchresults.aspx?Type=3&txtSearch=cataract&num=20