Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, NK-cell lymphoma, and myeloid leukemia

Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and NK-cell lymphoma

Mycosis fungoides

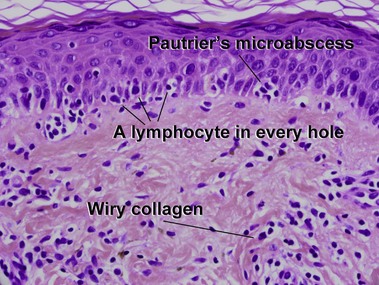

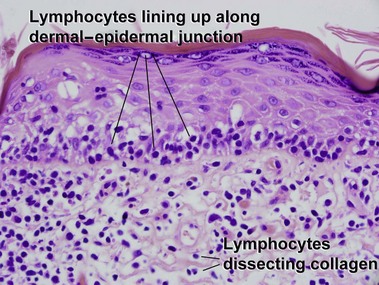

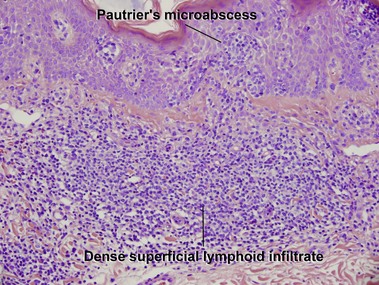

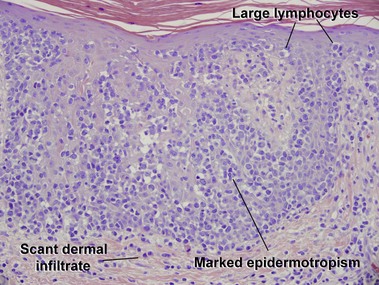

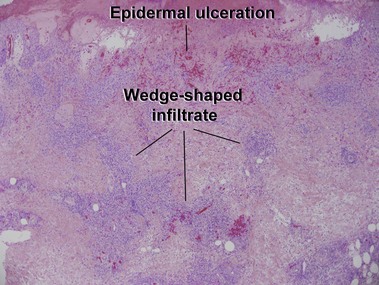

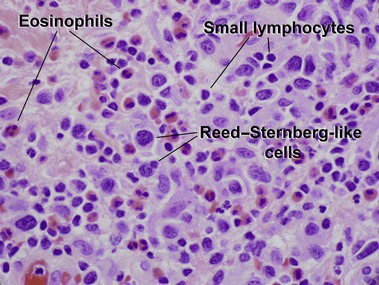

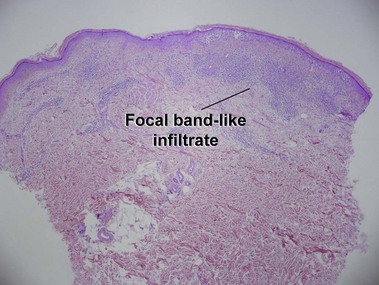

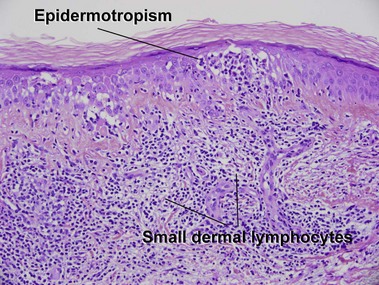

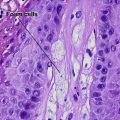

Patch stage

Table 24-1

Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas, NK-cell lymphomas, and precursor hematologic neoplasm in the 2008 WHO classification

Mature T-cell and NK-cell neoplasms

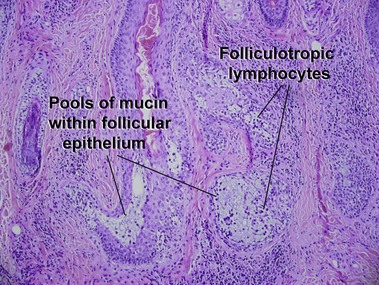

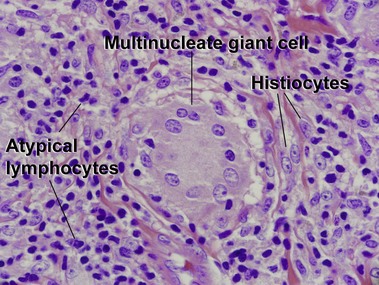

Mycosis fungoides variants and subtypes

Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma

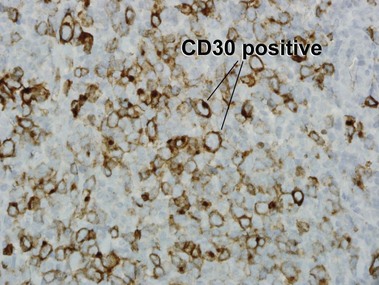

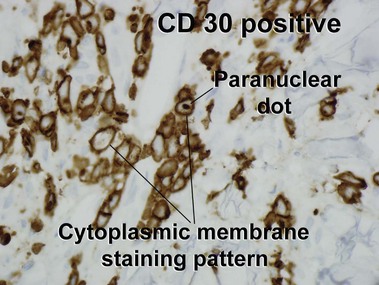

Primary cutaneous CD30+ T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders

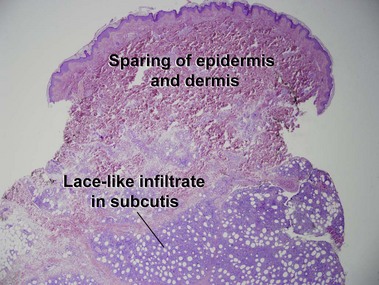

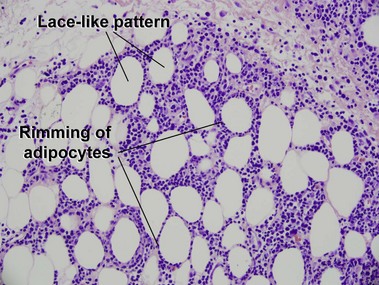

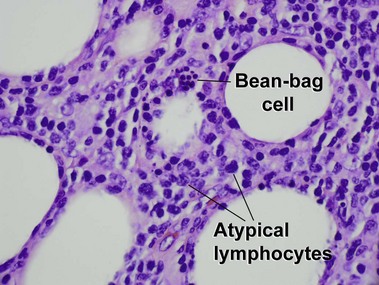

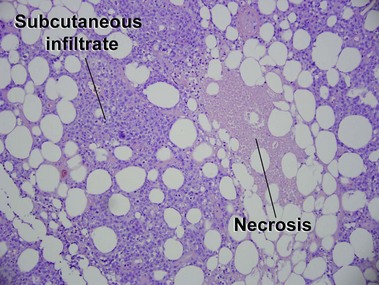

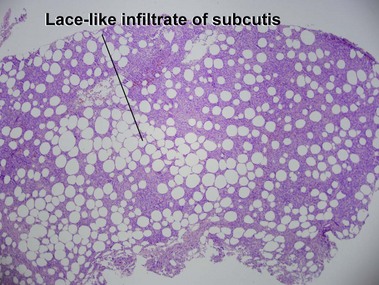

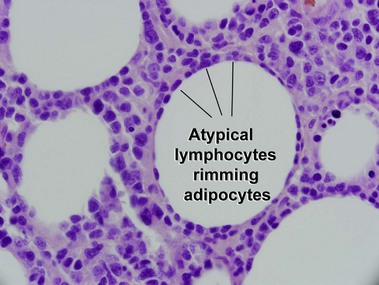

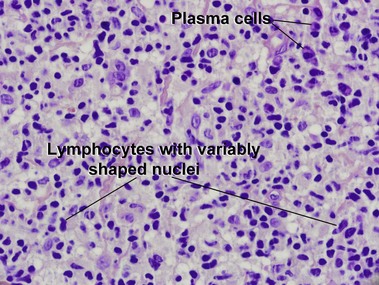

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma

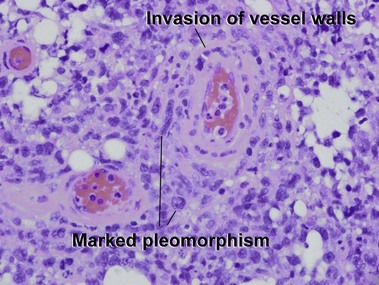

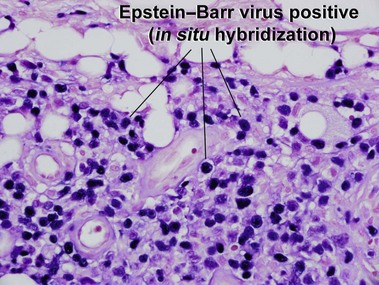

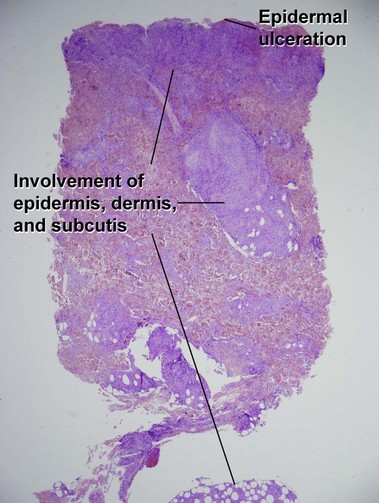

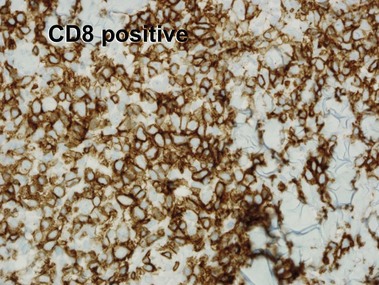

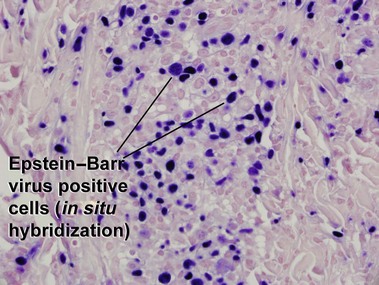

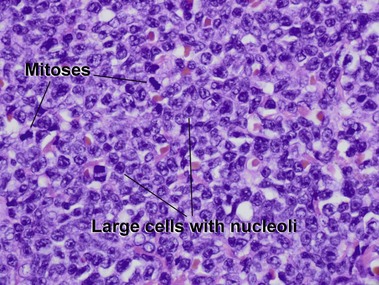

Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type

Precursor hematologic neoplasm

Adapted from WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn. Lyon, France: IARC; 2008.

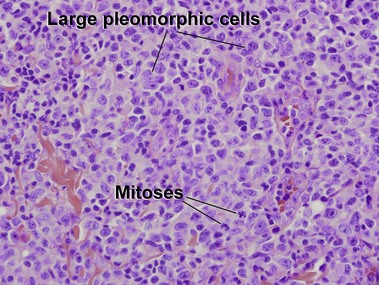

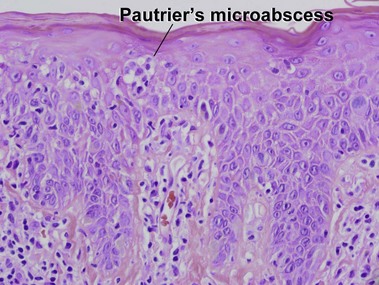

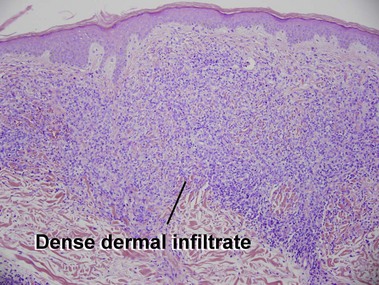

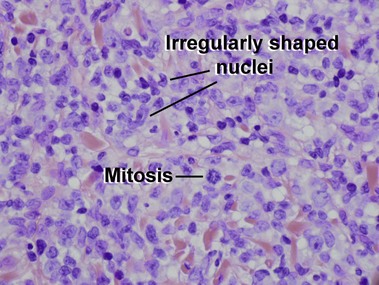

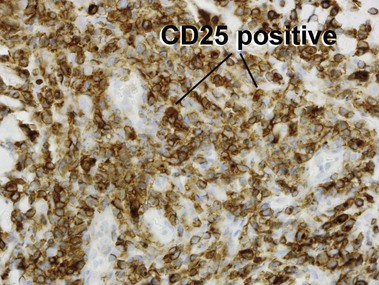

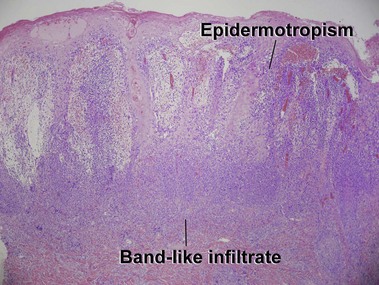

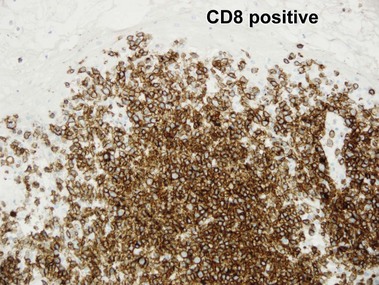

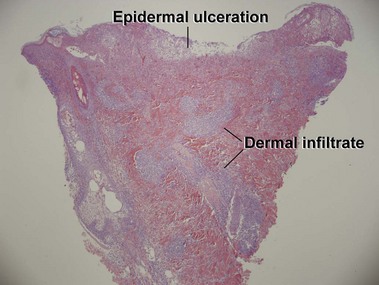

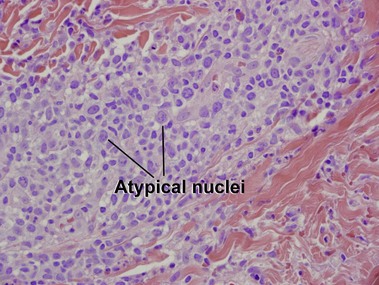

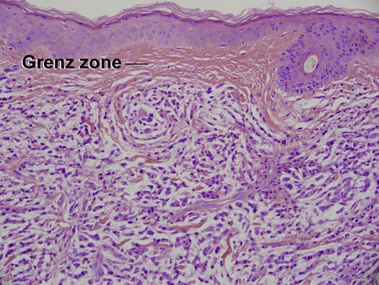

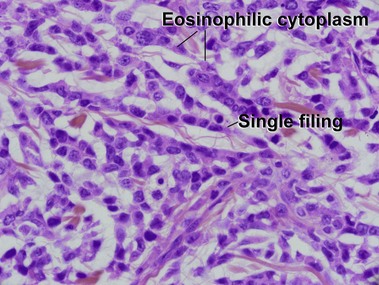

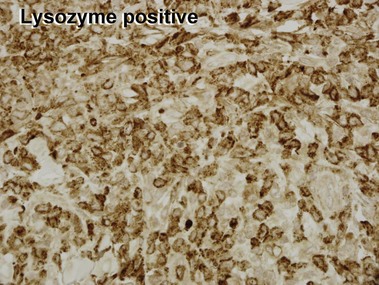

Mycosis fungoides (MF) is the most common type of cutaneous lymphoma. In most cases, the disease is indolent and slowly progressive over a period of years or decades. Three main stages of the lymphoma are recognized: patch, plaque, and tumor stages. In the patch stage of mycosis fungoides, patients typically present with broad pink or tan oval-shaped patches with a predilection for the bathing trunk area. The patches may be asymptomatic or pruritic. Both clinically and histopathologically, distinction from eczematous dermatitis is sometimes difficult in the earliest stages of the lymphoma. In the evaluation of patch stage mycosis fungoides, multiple shave biopsies are often helpful, since the shave technique provides a broad area of epidermis for examination. The typical immunophenotype is CD3+, CD4+, CD8−, CD30−. Aberrant immunophenotypes (with loss of normal T-cell markers, such as CD7) can frequently be demonstrated. Clonal rearrangement of the T-cell receptor gene is helpful in supporting the diagnosis, although the earliest cases may sometimes not have a detectable clone.

Primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders

Battistella, M, Beylot-Barry, M, Bachelez, H, et al. Primary cutaneous follicular helper T-cell lymphoma. Arch Dermatol. 2012; 148:832–839.

Beltraminelli, H, Leinweber, B, Kerl, H, et al. Primary cutaneous CD4+ small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a cutaneous nodular proliferation of pleomorphic T lymphocytes of undetermined significance? A study of 136 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009; 31:317–322.

Bittencourt, AL, Barbosa, HS, Vieira, MD, et al. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (ATL) presenting in the skin: clinical, histological and immunohistochemical features of 52 cases. Acta Oncol. 2009; 48:598–604.

Campbell, JJ, Clark, RA, Watanabe, R, et al. Sezary syndrome and mycosis fungoides arise from distinct T-cell subsets: a biologic rationale for their distinct clinical behaviors. Blood. 2010; 116:767–771.

Cota, C, Vale, E, Viana, I, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm – morphologic and phenotypic variability in a series of 33 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:75–87.

El Shabrawi-Caelen, L, Kerl, H, Cerroni, L. Lymphomatoid papulosis: reappraisal of clinicopathologic presentation and classification into subtypes A, B, and C. Arch Dermatol. 2004; 140:441–447.

Fernandez-Flores, A. Comments on cutaneous lymphomas: since the WHO-2008 classification to present. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012; 34:274–284.

Gerami, P, Guitart, J. The spectrum of histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings in folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31:1430–1438.

Kaddu, S, Zenahlik, P, Beham-Schmid, C, et al. Specific cutaneous infiltrates in patients with myelogenous leukemia: a clinicopathologic study of 26 patients with assessment of diagnostic criteria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 40:966–978.

Kempf, W, Kazakov, DV, Schärer, L, et al. Angioinvasive lymphomatoid papulosis: a new variant simulating aggressive lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2013; 37:1–13.

Kempf, W, Ostheeren-Michaelis, S, Paulli, M, et al. Granulomatous mycosis fungoides and granulomatous slack skin. Arch Dermatol. 2008; 144:1609–1617.

Kempf, W, Sander, CA. Classification of cutaneous lymphomas – an update. Histopathology. 2010; 56:57–70.

Lee, J, Viakhireva, N, Cesca, C, et al. Clinicopathologic features and treatment outcomes in Woringer-Kolopp disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008; 59:706–712.

Massone, C, El-Shabrawi-Caelen, L, Kerl, H, et al. The morphologic spectrum of primary cutaneous anaplastic large T-cell lymphoma: a histopathologic study on 66 biopsy specimens from 47 patients with report of rare variants. J Cutan Pathol. 2008; 35:46–53.

Nofal, A, Abdel-Mawla, MY, Assaf, M, et al. Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ T-cell lymphoma: proposed diagnostic criteria and therapeutic evaluation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67:48–59.

Rodríguez-Pinilla, SM, Barrionuevo, C, Garcia, J, et al. EBV-associated cutaneous NK/T-cell lymphoma: review of a series of 14 cases from Peru in children and young adults. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:1773–1782.

Saggini, A, Gulia, A, Argenyi, Z, et al. A variant of lymphomatoid papulosis simulating primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell lymphoma. Description of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010; 34:1168–1175.

Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al, eds. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues, 4th edn, Lyon: IARC, 2008.

Willemze, R, Jaffe, ES, Burg, G, et al. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2005; 105:3768–3785.

Willemze, R, Jansen, PM, Cerroni, L, et al. Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma: definition, classification, and prognostic factors: an EORTC cutaneous lymphoma group study of 83 cases. Blood. 2008; 111:838–845.

Xu, Z, Lian, S. Epstein-Barr virus-associated hydroa vacciniforme-like cutaneous lymphoma in seven Chinese children. Pediatr Dermatol. 2010; 27:463–469.