98

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphoma

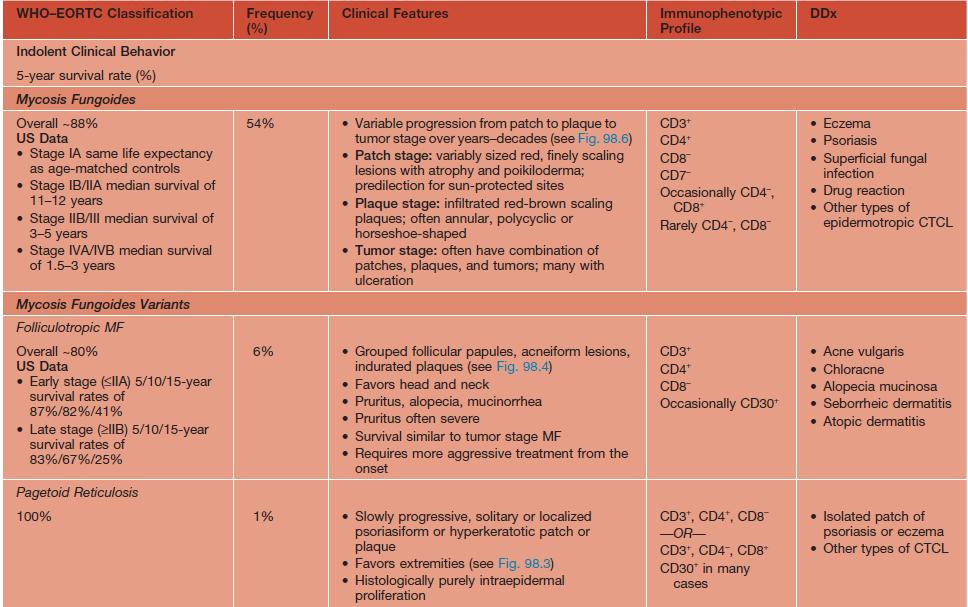

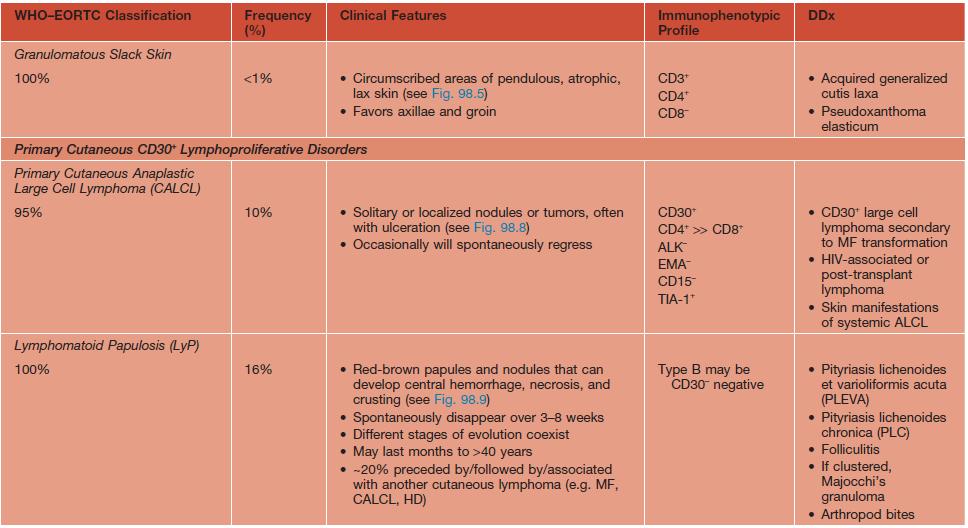

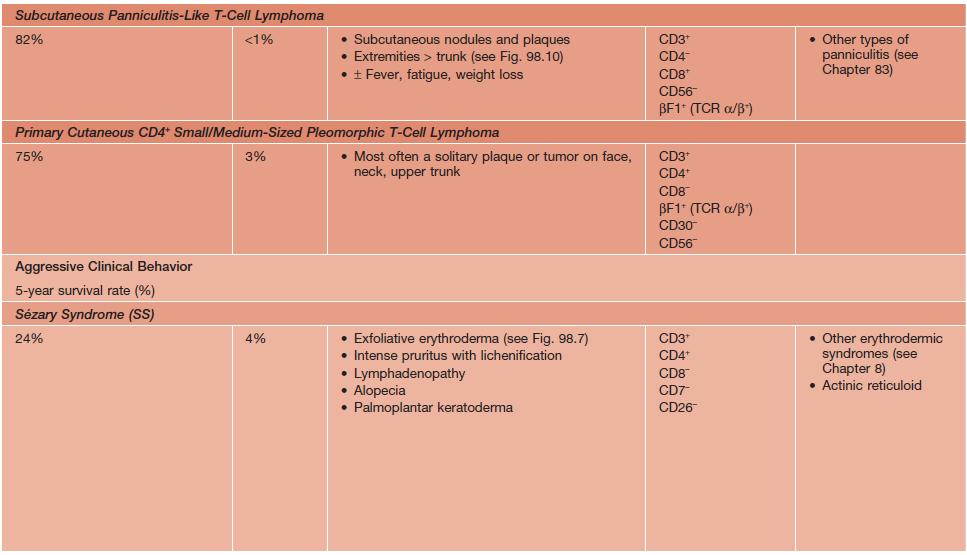

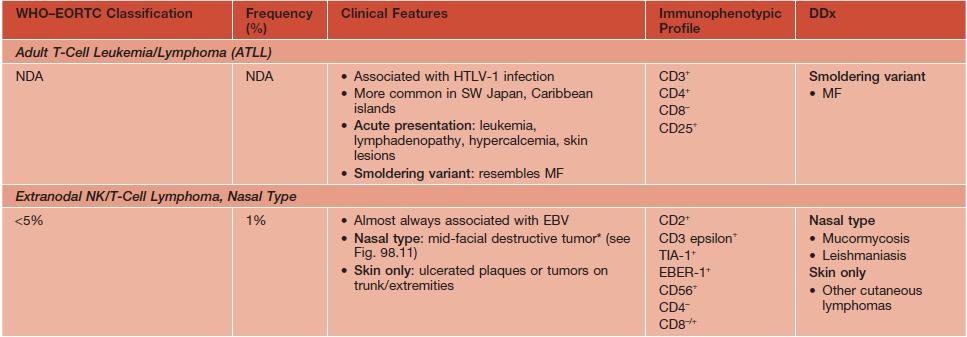

• The term CTCL will be used herein to describe the heterogeneous group of primary cutaneous lymphomas composed of neoplastic T cells or natural killer (NK) cells (Table 98.1).

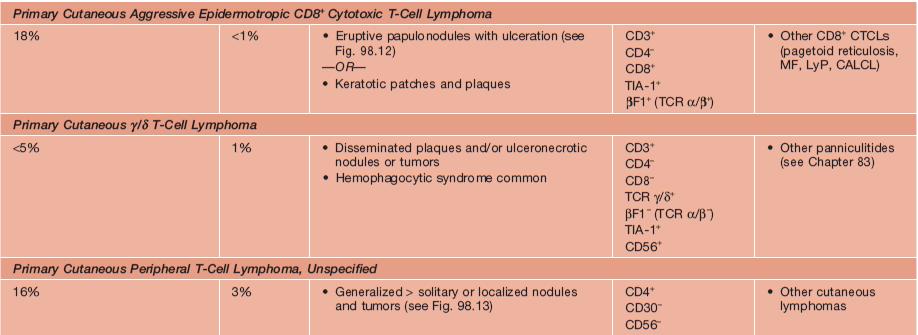

Table 98.1

WHO–EORTC classification for and features of cutaneous T-cell lymphomas.

* Previously called lethal midline granuloma.

NDA, no data available; EBV, Epstein-Barr virus; HD, Hodgkin disease; HTLV-1, human T-lymphotrophic virus 1; TCR, T-cell receptor.

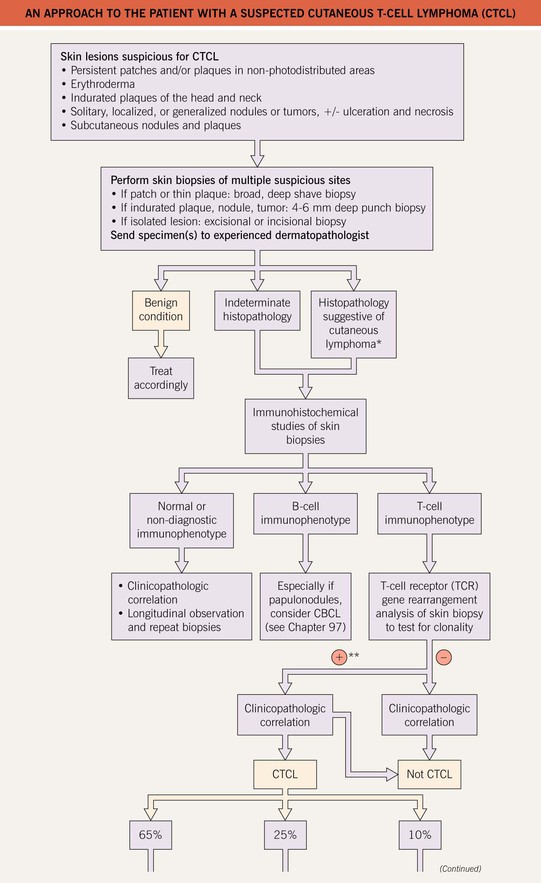

• An approach to the evaluation of a patient with suspected CTCL is presented in Fig. 98.1.

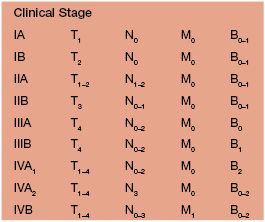

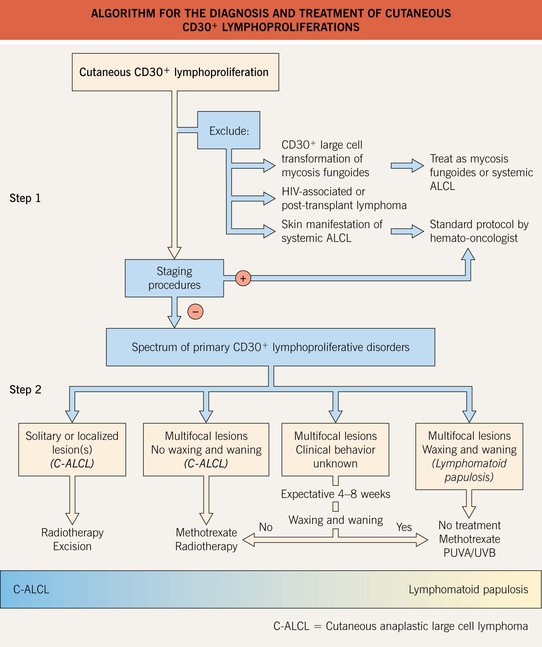

• Of the various CTCLs, approximately 65% are mycosis fungoides (MF), MF variants, or Sézary syndrome (SS) (see Table 98.1); 25% are within the spectrum of CD30+ lymphoproliferative disorders (see Table 98.1 and Fig. 98.2); and the remainder (10%) are composed of other rare entities (see Table 98.1).

Fig. 98.2 Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of primary cutaneous CD30+ lymphoproliferations. Brentuximab targets CD30 and is used to treat systemic ALCL. From Bekkenk M, Geelen FAMJ, van Voorst Vader PC, et al. Primary and secondary cutaneous CD30-positive lymphoproliferative disorders: long term follow-up data of 219 patients and guidelines for diagnosis and treatment. A report from the Dutch Cutaneous Lymphoma Group. Blood. 2000;95:3653–61.

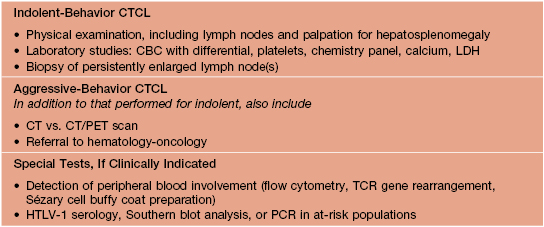

• In general, the aggressive-behaving CTCLs (see Tables 98.1 and 98.2) require more extensive staging, referral to a hematologist–oncologist, and systemic chemotherapy or targeted immunotherapy (e.g. rituximab, brentuximab).

Table 98.2

Recommended staging evaluation for indolent- and aggressive-behavior cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL).

CBC, complete blood count; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TCR, T-cell receptor; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; CT, computed tomography; PET, positron emission tomography.

Mycosis Fungoides (MF)

• The most common subtype of CTCL, representing about 50% of all primary cutaneous lymphomas.

• Other clinical variants with similar behavior include hypo- and hyperpigmented MF and bullous MF.

• Three rare clinical variants of MF with distinctive clinicopathologic features are considered separately, namely pagetoid reticulosis (Fig. 98.3), folliculotropic MF (Fig. 98.4), and granulomatous slack skin (Fig. 98.5).

Fig. 98.4 Folliculotropic mycosis fungoides. Infiltrated erythematous plaques and acneiform lesions on the forehead and eyebrows with concurrent hair loss. The infiltration, thickening, and accentuation of the skin folds is referred to as a ‘leonine facies.’ Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.5 Granulomatous slack skin. Pendulous fold of atrophic lax skin in the right inguinal area. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

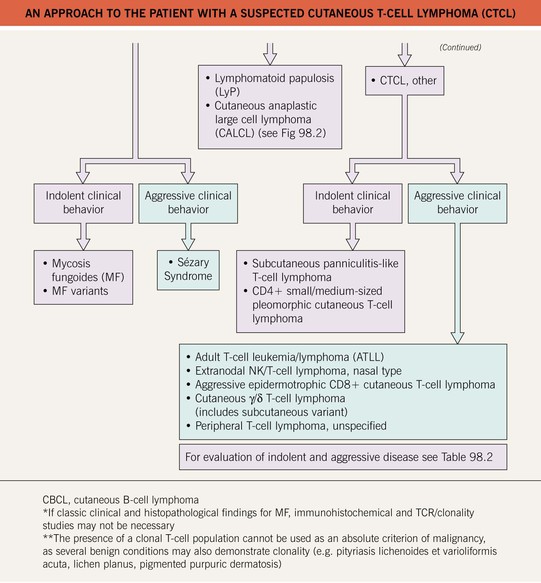

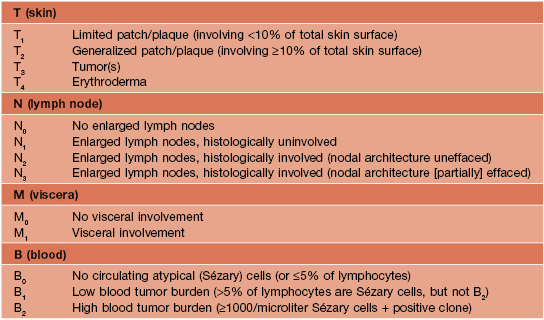

• Clinical presentation depends on stage at diagnosis (Tables 98.3 and 98.4), but classically patients progress from persistent patch/plaque stage to tumor stage over years to decades (Fig. 98.6).

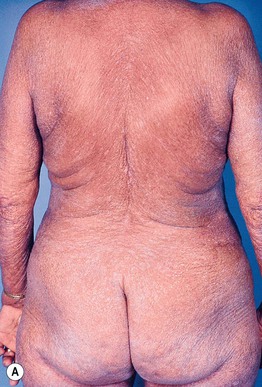

Fig. 98.6 Mycosis fungoides. A Limited patch/plaque stage disease (stage 1A). Patches on the buttocks, involving less than 10% of the skin surface. B Generalized patch/plaque disease (stage 1B). Extensive patches and plaques involving more than 10% of the skin surface. C Tumor stage. Multiple skin tumors in combination with typical patches and plaques. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

• Most patients have years of nonspecific eczematous or psoriasiform skin lesions and nondiagnostic biopsies before a definitive diagnosis of MF is made.

• Extracutaneous disease is extremely rare in patch/plaque stage, uncommon with generalized plaques, and most likely with extensive tumors or erythroderma.

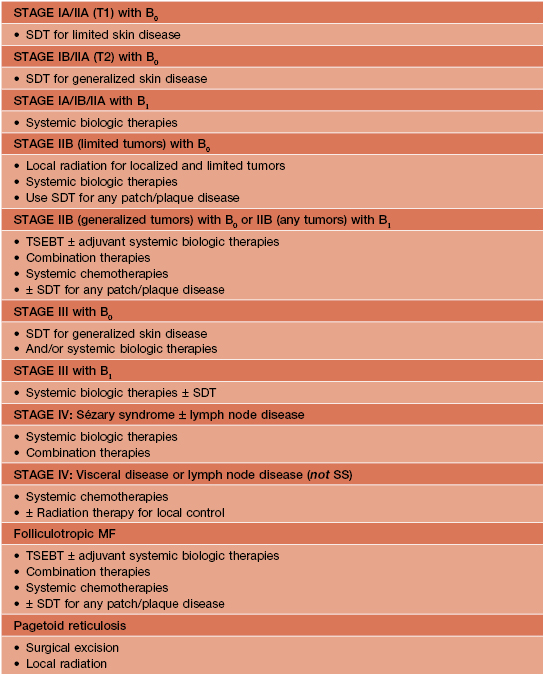

• Treatment is dependent on the stage at diagnosis, the host’s immune status, and the general condition of the patient (Table 98.5).

Table 98.5

Primary treatment of mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS) based on clinical stage.

SDT, skin directed therapy; TSEBT, total skin electron beam therapy.

• Available therapies are effective in controlling disease but usually do not prolong life.

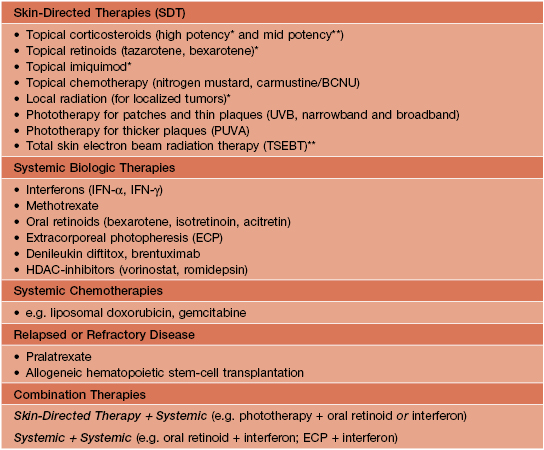

• Three main treatment categories are available: (1) skin-directed therapies (SDT); (2) systemic biologic therapies; and (3) systemic chemotherapies; combination therapy is also utilized (Table 98.6).

Table 98.6

Treatment options for mycosis fungoides (MF) and Sézary syndrome (SS).

* Limited skin disease.

** Generalized skin disease.

• Prognosis depends on stage, the type and extent of skin lesions, and the presence of extracutaneous disease (see Table 98.3).

Sézary Syndrome (SS)

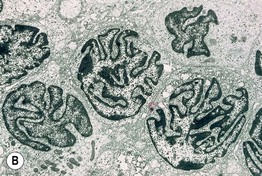

• Defined historically by the triad of (1) erythroderma; (2) generalized lymphadenopathy; and (3) the presence of neoplastic T cells (Sézary cells) in the skin, lymph nodes, and peripheral blood (Fig. 98.7).

Fig. 98.7 Sézary syndrome. A Diffuse erythroderma is present. B Electron photomicrograph of a skin biopsy showing characteristic Sézary cells. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.8 Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Characteristic clinical presentation with a solitary ulcerating tumor. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.9 Lymphomatoid papulosis (LyP). Clinical presentation with papulonecrotic skin lesions at different stages of evolution. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.10 Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma (SPTCL). Pink nodular skin lesions (arrowhead) as well as an area of lipoatrophy (arrow) at the site of a resolved nodule. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.11 Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type. An extensive ulceronecrotic nasal mass, previously referred to as lethal midline granuloma. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.12 Aggressive epidermotropic CD8+ cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Generalized skin tumors with central ulceration. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

Fig. 98.13 Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified. Rapidly growing nodules and tumors. Note: The skin lesions in the left upper corner do not represent patches but, rather, deep plaques present for 2 weeks. Courtesy, Rein Willemze, MD.

• Prognosis is generally poor and most patients die from opportunistic infections due to immunosuppression.

• Systemic treatment is required, with skin-directed therapies sometimes being used as adjuvant therapy (see Tables 98.4 and 98.5).

For further information see Ch. 120. From Dermatology, Third Edition.