Chapter 643 Cutaneous Nevi

Nevus skin lesions are characterized histopathologically by collections of well-differentiated cell types normally found in the skin. Vascular nevi are described in Chapter 642. Melanocytic nevi are subdivided into 2 broad categories: those that appear after birth (acquired nevi) and those that are present at birth (congenital nevi).

Acquired Melanocytic Nevus

Prognosis and Treatment

Acquired pigmented nevi are benign, but a very small percentage undergoes malignant transformation. Suspicious changes are indications for excision and histopathologic evaluation; they include rapid increase in size; development of satellite lesions; variegation of color, particularly with shades of red, brown, gray, black, and blue; pigmentary incontinence; notching or irregularity of the borders; changes in texture such as scaling, erosion, ulceration, and induration; and regional lymphadenopathy. Most of these changes are due to irritation, infection, or maturation; darkening and gradual increase in size and elevation normally occur during adolescence and should not be cause for concern. Two common benign changes are clonal nevi (fried-egg moles) and rim nevi. A clonal nevus is light brown with a dark raised center representing a clonal change of a subset of nevus cells within the lesion. Rim nevi are flat and light brown with dark brown rims. They are seen primarily in the scalp (Fig. 643-1). Consideration should be given to the presence of risk factors for development of melanoma and the patient’s parents’ wishes about removal of the nevus. If doubt remains about the benign nature of a nevus, excision is a safe and simple outpatient procedure that may be justified to allay anxiety.

Congenital Melanocytic Nevus

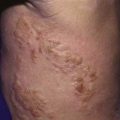

Giant congenital pigmented nevi (<1/20,000 births) occur most commonly on the posterior trunk (Fig. 643-2) but may also appear on the head or extremities. These nevi are of special significance because of their association with leptomeningeal melanocytosis (neurocutaneous melanocytosis) and their predisposition for development of malignant melanoma. Leptomeningeal involvement occurs most often when the nevus is located on the head or midline on the trunk, particularly when associated with multiple “satellite” melanocytic nevi (>20 lesions). Nevus cells within the leptomeninges and brain parenchyma may cause increased intracranial pressure, hydrocephalus, seizures, retardation, and motor deficits and may result in melanoma. Malignancy can be identified by careful cytologic examination of the cerebrospinal fluid for melanin-containing cells. MRI demonstrates asymptomatic leptomeningeal melanosis in ≈ 30% of individuals with giant congenital nevus of the type described above. The overall incidence of malignant melanoma arising in a giant congenital nevus has been estimated to be ≈ 5-10% but is more likely to be approximately 1-2%. The median age at diagnosis of the melanomas that arise within a giant congenital nevus is 7 yr. The mortality rate approaches 100%. The risk of melanoma is greater in patients in whom the predicted adult size of the nevus is > 40 cm. Management of giant congenital nevi remains controversial and should involve the parents, pediatrician, dermatologist, and plastic surgeon. If the nevus lies over the head or spine, MRI may allow detection of neural melanosis, the presence of which makes gross removal of a nevus from the skin a futile effort. In the absence of neural melanosis, early excision and repair aided by tissue expanders or grafting may reduce the burden of nevus cells and thus the potential for development of melanoma, but at the cost of many potentially disfiguring operations. Nevus cells deep within subcutaneous tissues may evade excision. Random biopsies of the nevus are not helpful, but biopsy of newly expanding nodules is indicated. Follow-up every 6 mo for 5 yr and every 12 mo thereafter is recommended. Serial photographs of the nevus may aid in detecting changes.

Halo Nevus

Halo nevi occur primarily in children and young adults, most commonly on the back (Fig. 643-3). Development of the lesion may coincide with puberty or pregnancy. Several pigmented nevi frequently develop halos simultaneously. Subsequent disappearance of the central nevus over several months is the usual outcome, and the depigmented area usually repigments. Excision and histopathologic examination of the lesion is indicated only when the nature of the central lesion is in question. An acquired melanocytic nevus occasionally develops a peripheral zone of depigmentation over a period of days to weeks. There is a dense inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes and histiocytes in addition to the nevus cells. The pale halo reflects disappearance of the melanocytes. This phenomenon is associated with congenital nevi, blue nevi, Spitz nevi, dysplastic nevi, neurofibromas, and primary and secondary malignant melanoma, and occasionally with poliosis, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome, and pernicious anemia. Patients with vitiligo have an increased incidence of halo nevi. Individuals with halo nevi have circulating antibodies against the cytoplasm of melanocytes and nevus cells.

Spitz Nevus (Spindle and Epithelioid Cell Nevus)

Spitz nevus manifests most commonly in the 1st 2 decades of life as a pink to red, smooth, dome-shaped, firm, hairless papule on the face, shoulder, or upper limb (Fig. 643-4). Most are <1 cm in diameter, but they can achieve a size of 3 cm. Rarely, they occur as numerous grouped lesions. Visually similar lesions include pyogenic granuloma, hemangioma, nevocellular nevus, juvenile xanthogranuloma, and basal cell carcinoma, but these entities are histologically distinguishable. Spitz nevus may be difficult to distinguish histopathologically from malignant melanoma because nuclear atypia is a common feature, particularly after local recurrence of the nevus. Difficulty arises in the fact that many other clinical types of melanocytic nevi have a similar histologic appearance. Local recurrence after excision may occur up to 5% of the time. If a nevus arouses clinical suspicion that it may be a melanoma, an excisional biopsy of the entire lesion is recommended. If the margins of excision of a Spitz nevus are positive, re-excision of the site is prudent to avoid difficulties in histopathologic interpretation of the lesion in the future.

Nevus Spilus (Speckled Lentiginous Nevus)

Nevus spilus is a flat brown patch within which are darker flat or raised brown melanocytic elements (Fig. 643-5). It varies considerably in size and can occur anywhere on the body. The color of the macular component may vary from light to dark brown, and the number of darker lesions may be low or high. Nevus spilus is rare at birth and is commonly acquired in late infancy or early childhood. Dark elements within the nevus are usually present initially and tend to increase in number gradually over time. The darker macules represent nevus cells in a junctional or dermal location; the patch has increased numbers of melanocytes in a lentiginous epidermal pattern. The malignant potential of these nevi is uncertain; nevus spilus is found more commonly in individuals with melanoma than in matched control subjects. The nevi need not be excised, unless atypical features or recent clinical changes are noted.

Nevus Depigmentosus (Achromic Nevus)

Nevi depigmentosi are usually present at birth; they are localized macular hypopigmented patches or streaks, often with bizarre, irregular borders (Fig. 643-6). They can resemble hypomelanosis of Ito clinically, except that they are more localized and often unilateral. Small lesions may also resemble the ash leaf macules of tuberous sclerosis. Nevi depigmentosi appear to represent a focal defect in transfer of melanosomes to keratinocytes.

Epidermal Nevi

Epidermal nevi are classified into a number of variants, depending on the morphology and extent of the individual nevus and the predominant epidermal structure. An epidermal nevus may appear initially as a discolored, slightly scaly patch that, with maturation, becomes more linear, thickened, verrucous, and hyperpigmented. Systematized refers to a diffuse or extensive distribution of lesions, and ichthyosis hystrix indicates that the distribution is extensive and bilateral (Fig. 643-7). Morphologic types include pigmented papillomas, often in a linear distribution; unilateral hyperkeratotic streaks involving a limb and perhaps a portion of the trunk; velvety hyperpigmented plaques; and whorled or marbled hyperkeratotic lesions in localized plaques or over extensive areas of the body along Blaschko lines. An inflammatory linear verrucous variant is markedly pruritic and tends to become erythematous, scaling, and crusted.

Nevus Sebaceus (Jadassohn)

A relatively small, sharply demarcated, oval or linear, elevated yellow-orange plaque that is usually devoid of hair, nevus sebaceus occurs on the head and neck of infants (Fig. 643-8). It may occur occasionally on the trunk. Although the lesion is characterized histopathologically by an abundance of sebaceous glands, all elements of the skin are represented. It is frequently flat and inconspicuous in early childhood. With maturity, usually during adolescence, the lesions become verrucous and studded with large rubbery nodules. The changing clinical appearance reflects the histologic pattern, which is characterized by a variable degree of hyperkeratosis, hyperplasia of the epidermis, malformed hair follicles, and often a profusion of sebaceous glands and the presence of ectopic apocrine glands. It is believed that these nevi form from pluripotential primary epithelial germ cells, which can dedifferentiate into various epithelial tumors. Consequently, during adulthood, these nevi are frequently complicated by secondary malignancies and benign adnexal tumors, most commonly basal cell carcinoma or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Deletions in the PTCH gene, the putative gene defect in basal cell carcinoma, have been found in sebaceus nevi. The treatment of choice is total excision before adolescence. Sebaceus nevi associated with central nervous system, skeletal, and ocular defects represent a variant of the epidermal nevus syndrome.

Becker Nevus (Becker Melanosis)

Becker nevus develops predominantly in males, during childhood or adolescence, initially as a hyperpigmented patch. The lesion commonly develops hypertrichosis, limited to the area of hyperpigmentation, and evolves into a unilateral, slightly thickened, irregular, hyperpigmented plaque. The most common sites are the upper torso and upper arm (Fig. 643-9). The nevus shows an increased number of basal melanocytes and variable epidermal hyperplasia. Becker melanosis is commonly associated with a smooth muscle hamartoma, which may appear as slight perifollicular papular elevations or slight induration. Stroking of such a lesion may induce smooth muscle contraction and make the hairs stand up. The nevus is benign, has no risk for malignant change, and is rarely associated with other anomalies.

Smooth Muscle Hamartoma

Smooth muscle hamartoma is a developmental anomaly resulting from hyperplasia of the smooth muscle (arrector pili) associated with hair follicles. It is usually evident at birth or shortly thereafter as a flesh-colored or lightly pigmented plaque with overlying hypertrichosis on the trunk or limbs (Fig. 643-10). Transient elevation or a rippling movement of the lesion, caused by contraction of the muscle bundles, can sometimes be elicited by stroking of the surface. Smooth muscle hamartoma can be mistaken for congenital pigmented nevus, but the distinction is important because the former has no risk for malignant melanoma and need not be removed.

Altaykan A, Ersov-Evans S, Erkin G, et al. Basal carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceous during childhood. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:616-619.

Crane LA, Mokrohisky ST, Dellavalle RP, et al. Melanocytic nevus development in Colorado children born in 1998. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1-9.

Guidbakke KK, Khachemoune A, Deng A, et al. Naevus comedonicus: a spectrum of body involvement. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;32:488-492.

Gupta M, Berk DR, Gray C, et al. Morphologic features and natural history of scalp nevi in children. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(5):506-511.

Huynh PM, Grant-Kels JM, Grin CM. Childhood melanoma: update and treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:715-723.

Kazakov DV, Calonie E, Zelger B, et al. Sebaceous carcinoma arising in nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: a clinicopathological study of five cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:242-248.

Kinsler VA, Birley J, Atherton DJ. Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children registry for congenital melanocytic naevi: prospective study 1988–2007. Part 1: epidemiology, phenotype and outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:143-150.

Krengel S, Hauschild A, Schafer T. Melanoma risk in congenital melanocytic naevi: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155:1-8.

Schaffer JV. Pigmented lesions in children: when to worry. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2007;19:430-440.

Sulit DJ, Guardiano RA, Krvida S. Classic and atypical Spitz nevi: review of the literature. Cutis. 2007;79:141-146.

Xu AE, Huang B, Li YW, et al. Clinical, histopathological and ultrastructural characteristics of naevus depigmentosus. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:400-405.

Zaal LH, Mooi WJ, Klip H, et al. Risk of malignant transformation of congenital melanocytic nevi: a retrospective nationwide study from the Netherlands. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1902-1909.