93

Cutaneous Melanoma

• Some cutaneous melanomas (CMs) arise de novo, whereas others arise within precursor lesions (e.g. melanocytic nevi; see Chapter 92).

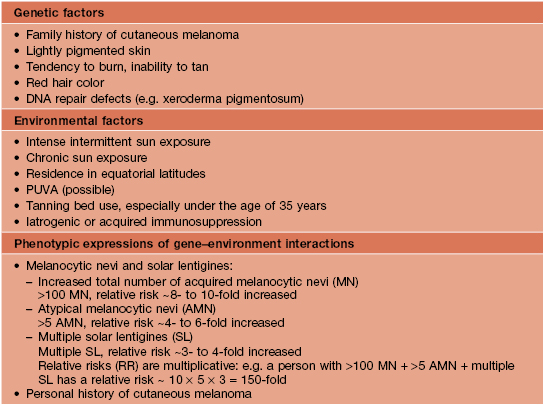

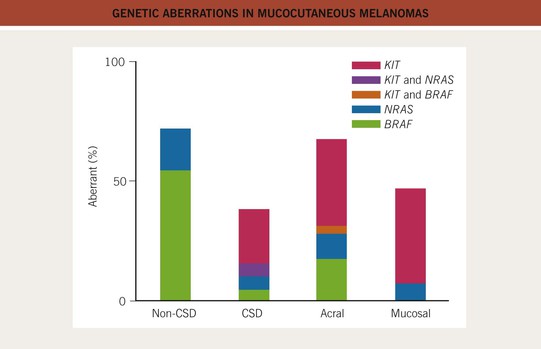

• Tremendous advances have been made in understanding the molecular pathways and mutations from which many CMs originate, resulting in identification of genetic markers, tools for aiding in the histologic diagnosis, and targeted treatments for CM (Figs. 93.1 and 93.2; see Table 93.11).

Fig. 93.1 Genetic aberrations in mucocutaneous melanomas. CSD, skin with chronic sun-induced changes such as marked solar elastosis; non-CSD, skin without chronic sun-induced damage. From Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:4340–4346.

Fig. 93.2 RAS-RAF-MEK-ERK (MAPK) and PI3K-AKT signaling pathways. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway is physiologically activated by growth factor binding to receptor tyrosine kinases. The stimulus is relayed to the nucleus via the GTPase activity of NRAS and the kinase activity of BRAF, MEK, and ERK. Within the nucleus, this results in increased transcription of genes involved in cell growth, proliferation and survival. The central role of this pathway in melanocytic neoplasia is highlighted by the fact that either NRAS or BRAF is mutated in approximately 80% of all cutaneous melanomas and melanocytic nevi. The PI3K-AKT pathway is another important regulator of cell survival, growth, and apoptosis. A key inhibitor of this pathway is PTEN, and inactivation of the gene that encodes PTEN via mutations, deletions, or promoter methylation also occurs in cutaneous melanomas. As a result, there is increased activity of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway. PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog. Adapted from Eggermont AM, Robert C. Melanoma in 2011: A new paradigm tumor for drug development. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2012;9:74–76.

Epidemiology

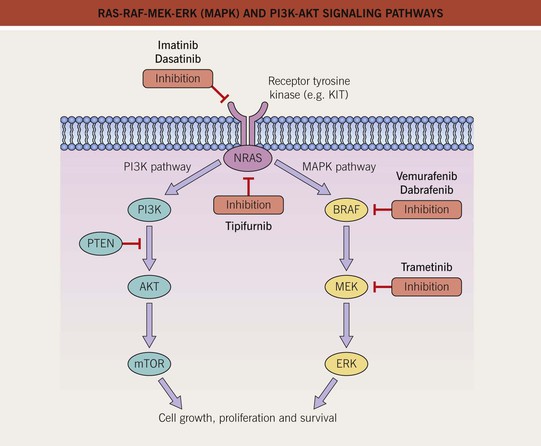

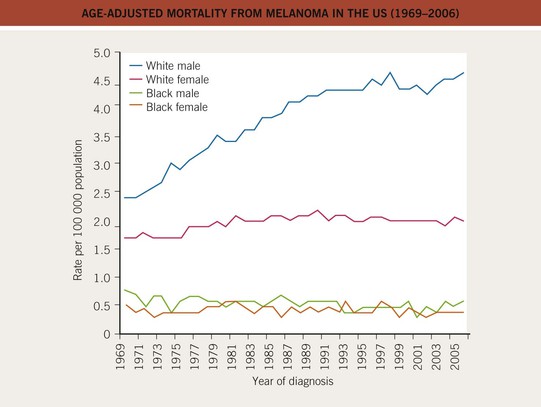

• There has been a marked increase in the incidence of CM during the past 40–50 years, with a modest increase in mortality, especially among older males (Figs. 93.3 and 93.4).

Fig. 93.3 Age-adjusted incidence rates of melanoma in the United States (1973–2007). The incidence has increased in the male and female Caucasian populations during the past three decades, and this trend has not yet stopped. The African-American population shows a constant low incidence, mostly caused by acral and mucosal melanomas. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute.

Fig. 93.4 Age-adjusted mortality from melanoma in the United States (1969–2006). The mortality has increased, especially for the male Caucasian population, during the past three decades. For females, the increase was less pronounced and has leveled off since the 1980s. Data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program of the National Cancer Institute.

• Death occurs at a younger age than for most other cancers.

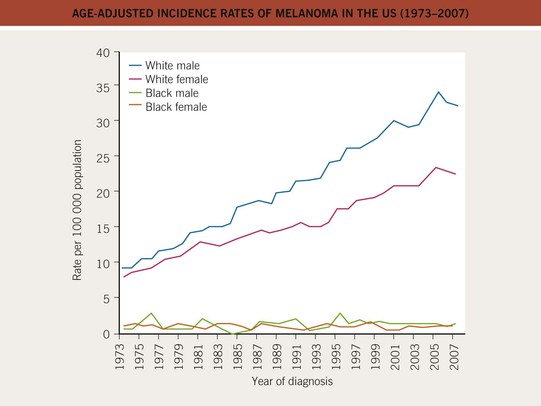

• Risk factors are divided into three major groups: genetic, environmental, and phenotypic (Table 93.1).

• Primary prevention: sun protective measures and avoidance of tanning beds.

Clinical

• The clinical presentation of CM varies greatly; although the ABCDE‘s (Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variegation, Diameter >6 mm, Evolution) are often used in public awareness campaigns to help promote the clinical recognition of CM, they have their shortcomings; to rectify this, the EFG rule (Elevated, Firm, Growing) has been added for nodular and amelanotic CMs.

• There are four major subtypes of primary invasive CM, based on clinicopathologic features:

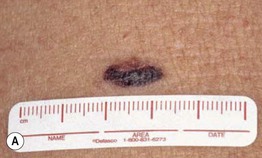

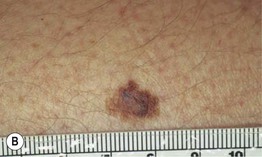

– Superficial spreading melanoma (SSM; ~60% of melanomas) (Fig. 93.5).

Fig. 93.5 Superficial spreading melanomas. A–C All of these early lesions demonstrate asymmetry due to variation in color and irregularity in outline. In addition, there is pink discoloration in (C). A, B were less than 0.5 mm in thickness and (C) was 0.8 mm. D In this more advanced lesion, note the asymmetry, irregular borders, variation in colors, scarlike regression zones, and an inferior pink papule, indicating vertical growth phase. E Superficial spreading melanoma arising within a compound melanocytic nevus. Note the irregular outline and variable pigmentation. A, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; B, C, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; D, Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

– Nodular melanoma (NM; ~20%) (Fig. 93.6).

Fig. 93.6 Nodular melanoma. Rapidly growing black nodule that was >15 mm in diameter on the back of a male patient. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

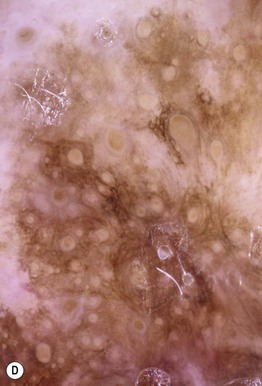

– Lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM; ~9%) (Fig. 93.7).

Fig. 93.7 Lentigo maligna (LM) and lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM). A Large-sized brown patch with some variation in color representing lentigo maligna. B Similarly sized lesion, but with marked variation in color and topography. There was invasion to a depth of 1.1 mm within the blue-gray papules, representing LMM. C LMM on the dorsal nose, with irregular borders, light to dark brown color, and marked asymmetry. D Dermoscopy of this lesion demonstrating annular structures corresponding to follicular openings surrounded by melanoma cells (‘circle in a circle’). B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD; C, D, Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

– Acral lentiginous melanoma (ALM; ~4%) (Fig. 93.8).

Fig. 93.8 Acral lentiginous melanoma. Irregularly pigmented lesion on the plantar surface of the foot. These tumors may become amelanotic and are then easily overlooked or misdiagnosed as verrucae or other benign lesions, often resulting in a significantly delayed diagnosis. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

• In cutaneous melanoma in situ (MIS), the malignancy is confined to the epidermis and/or the hair follicle epithelium (Fig. 93.9); all types of CM (except for NM) can have an in situ phase; lentigo maligna is a type of MIS that arises within chronically sun-damaged skin and can remain in situ for years to decades.

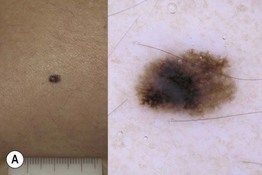

Fig. 93.9 Melanoma in situ. A Note the asymmetry, border irregularity, color variation, and erythema (‘little red riding hood’ sign). B The dermoscopic findings include a broadened network, dots, and some globules. C This melanoma in situ measured less than 3 mm in diameter. Small melanomas can be easily overlooked, especially if they are less heavily pigmented. This lesion was the ‘ugly duckling’ of all of this patient’s nevi. Dermoscopy assists in making an earlier diagnosis. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

– Amelanotic melanoma: color ranges from pink to red and any type of CM may be amelanotic (Fig. 93.10); children can develop amelanotic nodular CM, and the lesion may resemble a persistent arthropod bite or pyogenic granuloma.

Fig. 93.10 Amelanotic melanoma. A, B Skin-colored to light pink nodule on the right scapula of a female patient. Pathology revealed an amelanotic nodular melanoma with a tumor thickness of 4 mm. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

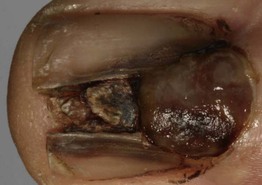

– Nail matrix melanoma: see Table 58.3 and Fig. 93.11.

Fig. 93.11 Melanoma of the nail matrix. Ulcerated tumor destroying the nail plate. The longitudinal pigmentation of the nail plate adjacent to the nodular portion is a clue to the diagnosis of melanoma. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

• Childhood CM is rare; prepubertal patients tend to have thicker lesions that can be difficult to distinguish from atypical Spitz nevi histologically, and overall the prognosis is favorable.

Diagnosis

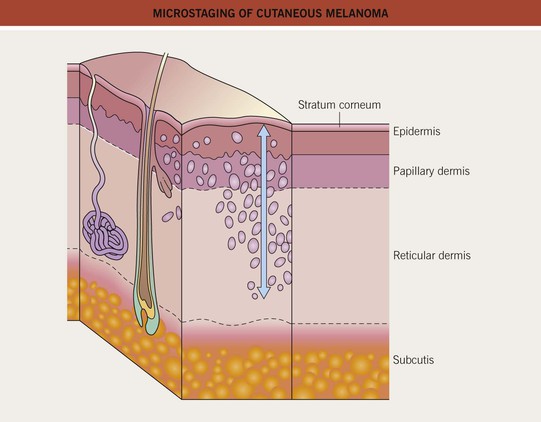

• The biopsy should attempt to remove the entire lesion, including a depth adequate to determine an accurate Breslow depth (Fig. 93.12); if limited by large size, representative samples should be obtained; evaluation is then performed by a dermatopathologist.

Fig. 93.12 Microstaging of cutaneous melanoma: Breslow tumor thickness. Breslow method: measure in millimeters from the top of the granular layer of the epidermis (or the base of an ulcer) to the deepest part of the tumor.

• When doing a total body skin examination (TBSE), signs such as the ‘ugly duckling sign’ (a pigmented lesion that stands out as atypical within the context of surrounding nevi; see Fig. 93.9C and Chapter 92) and the ‘little red riding hood sign’ can prove useful (see Fig. 93.9A).

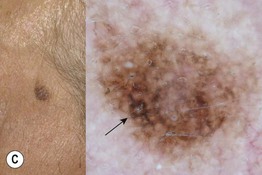

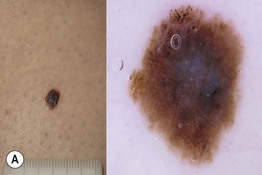

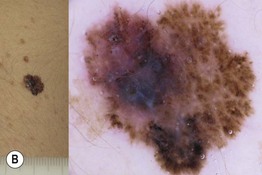

• Photography and dermoscopy can aid in diagnosis (Figs. 93.13 and 93.14); for the latter, the first step is to determine if the lesion is melanocytic (Table 93.2) and then assess for worrisome features (Tables 93.3 and 93.4).

Fig. 93.13 The four most common types of cutaneous melanoma. A Small superficial melanoma typified dermoscopically by asymmetry of color and structure, atypical network, blue-white structures, and irregular streaks at the periphery. B Large thick nodular melanoma with predominant blue-white veil. The combination of blue color with irregular black to brown dots, globules, and blotches is highly specific for the diagnosis of thick melanoma. C Small facial melanoma in situ (lentigo maligna) typified by gray color and rhomboidal structures (arrow) by dermoscopy. D Acral melanoma in situ typified by the characteristic parallel-ridge pattern. Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, and Iris Zalaudek, MD.

Fig. 93.14 Dermoscopy of an in situ and an invasive superficial cutaneous melanoma. A Melanoma in situ typified dermoscopically by asymmetry of color and structure, atypical network, blue-white structures centrally, and irregular black dots and globules (at the upper portion of the lesion). B Melanoma 0.9 mm in depth. Clinically, a palpable area is visible, corresponding dermoscopically to the presence of blue-white veil, a sign of increased tumor thickness. Irregular dots and globules, irregular streaks at the periphery, and uneven brown to black pigmented areas (blotches) are also observed. Courtesy, Giuseppe Argenziano, MD, and Iris Zalaudek, MD.

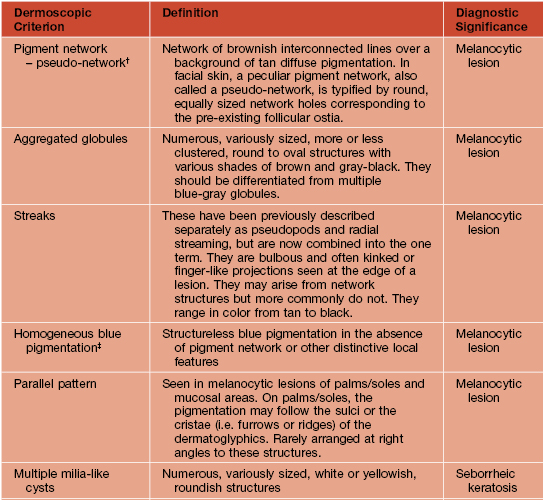

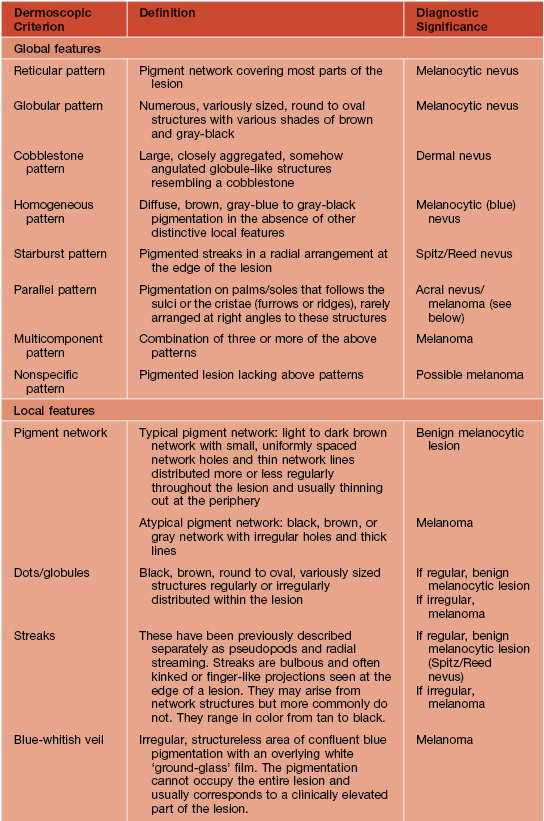

Table 93.2

Dermoscopic pattern analysis: first-step algorithm for differentiation between melanocytic and non-melanocytic lesions.

* To diagnose a basal cell carcinoma, the negative feature of pigment network must be absent and one or more of the positive features listed here must be present.

† Exception 1: Pigment network or pseudo-network is also present in solar lentigo and rarely in seborrheic keratosis and pigmented actinic keratosis. A delicate, annular pigment network is also commonly seen in dermatofibroma and accessory nipple (clue for diagnosis of dermatofibroma and accessory nipple: central white patch).

‡ Exception 2: Homogeneous blue pigmentation (dermoscopic hallmark of blue nevus) is also seen (uncommonly) in some hemangiomas and basal cell carcinomas and (commonly) in intradermal melanoma metastases.

§ Exception 3: Ulceration is also seen less commonly in invasive melanoma.

Adapted from Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: Results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;48:679–693.

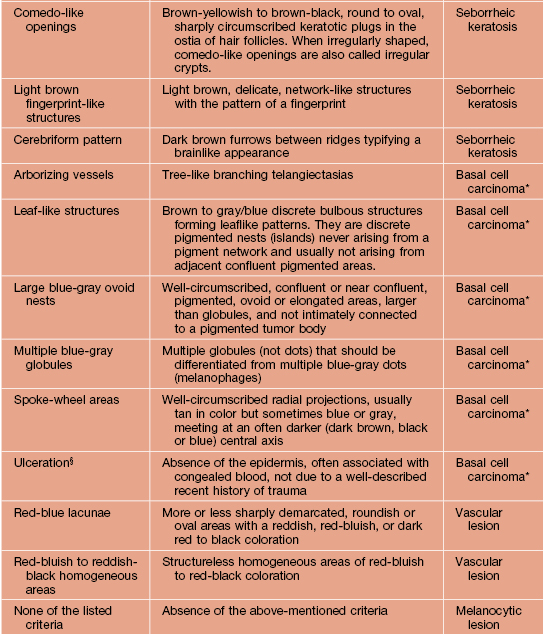

Table 93.3

Dermoscopic pattern analysis: second-step algorithm for differentiation between melanocytic nevi and melanoma.

Adapted from Argenziano G, Soyer HP, Chimenti S, et al. Dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions: Results of a consensus meeting via the Internet. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003;48:679–693.

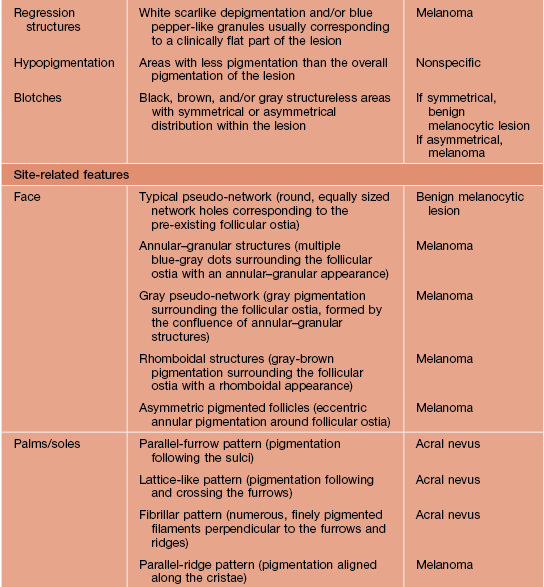

Table 93.4

Definitions of dermoscopic criteria for the 3-point checklist.

The presence of more than one criterion suggests a suspicious lesion.

| Criterion | Definition |

| Asymmetry | Asymmetrical distribution of colors and dermoscopic structures |

| Atypical network* | More than one type of network (in terms of color and thickness of the meshes) irregularly distributed within the lesion |

| Blue-white structures† | Presence of any type of blue and/or white color |

* Usually found in early melanoma.

† Usually found in both melanoma and pigmented basal cell carcinoma.

Adapted from Argenziano G, Puig S, Zalaudek I, et al. Dermoscopy improves accuracy of primary care physicians to triage lesions suggestive of skin cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2006;24:1877–1882.

• DDx: outlined in Table 93.5.

Table 93.5

Differential diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma.

BCC, basal cell carcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

Prognosis and Staging

• Of the histologic features of a primary invasive CM, the Breslow depth (in millimeters) is the strongest predictor of survival (see Fig. 93.12); the presence or absence of lymph node involvement is an even stronger predictor of survival.

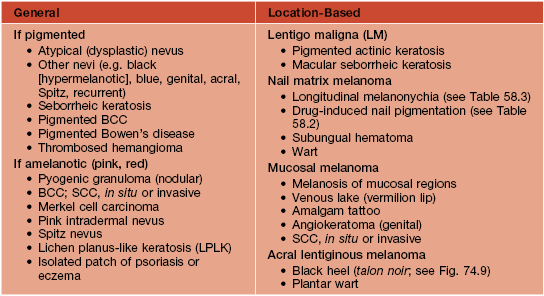

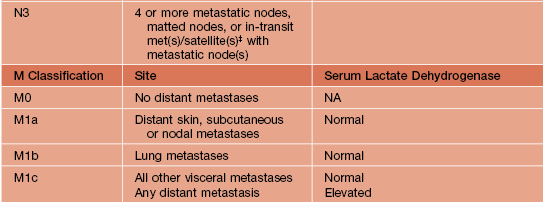

• The American Joint Committee on Cancer’s (AJCC) TNM classification and staging system for CM are outlined in Tables 93.6 and 93.7.

Table 93.6

Melanoma TNM classification.

For defining T1 melanomas, Clark level of invasion is used as default criterion only if mitotic rate cannot be determined. Histologic evaluation of lymph nodes must include at least one immunohistochemical marker (e.g. HMB45, Melan-A/MART-1).

* Micrometastases are diagnosed after sentinel or elective lymphadenectomy.

† Macrometastases are defined as clinically detectable nodal metastases confirmed by therapeutic lymphadenectomy or when nodal metastasis exhibits gross extracapsular extension.

‡ In-transit metastases are >2 cm from the primary tumor but not beyond the regional lymph nodes, whereas satellite lesions are within 2 cm of the primary.

NA, not applicable.

Adapted from Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. Reprinted with permission from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

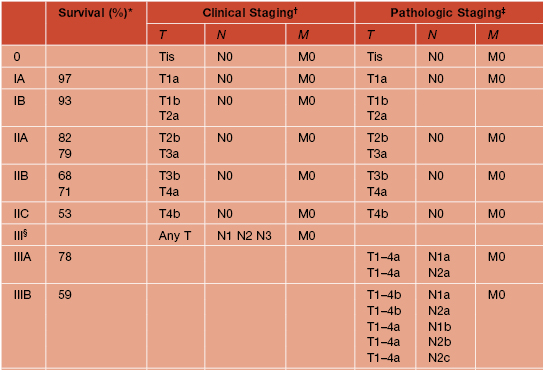

Table 93.7

Stage groupings for cutaneous melanoma.

* Approximate 5-year survival (%), modified from Balch et al. (2009).

† Clinical staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and clinical/radiologic evaluation for metastases. By convention, it should be used after complete excision of the primary melanoma with clinical assessment for regional and distant metastases.

‡ Pathologic staging includes microstaging of the primary melanoma and pathologic information about the regional lymph nodes after partial or complete lymphadenectomy. Pathologic stage 0 or stage IA patients are the exception.

§ There are no stage III subgroups for clinical staging.

|| Higher survival rate associated with normal serum LDH levels and lower rate with elevated LDH levels.

Adapted from Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009;27:6199–6206. Reprinted with permission from the American Society of Clinical Oncology.

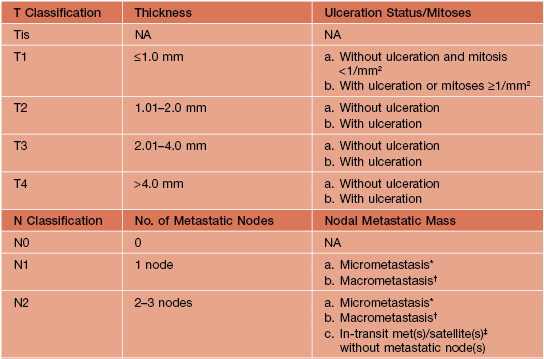

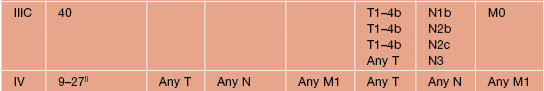

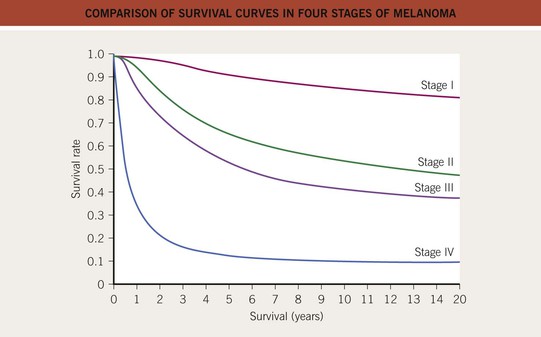

• As with other cancers, prognosis is dependent on the stage at the time of diagnosis (Fig. 93.15); other independent prognostic factors for survival have also been identified (Table 93.8).

Fig. 93.15 Comparison of survival curves in four stages of melanoma. Redrawn from Balch CM. Melanoma of the skin. In Edge SB, Byrd DR, Compton CC, et al., eds., AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 7th edn. New York: Springer, 2009.

Table 93.8

Major independent prognostic factors for survival in multivariate analyses.

| Prognostic Factor | Commentary |

| Tumor thickness | ≤1 mm, low risk; >1 mm, higher risk melanoma |

| Ulceration | Worse prognosis with ulceration |

| Mitotic rate | Worse prognosis with ≥1 mitoses/mm2 |

| Age | Worse prognosis with older age |

| Sex | Men have poorer prognosis (only for localized disease) |

| Anatomic site | Trunk, head, and neck associated with poorer prognosis than extremities |

| Number of involved lymph nodes | Cutoff points: 1, 2–3, 4 or more lymph nodes (see Table 93.6) |

| Regional lymph node tumor burden | Macroscopic (palpable) nodal metastases with poorer prognosis than microscopic (nonpalpable) nodal metastases |

| Site of distant metastases | Visceral metastases associated with poorer prognosis than nonvisceral metastases (skin, subcutaneous, distant lymph nodes) |

Management

• Once the histologic diagnosis of CM is confirmed, evaluation includes TBSE and palpation of the surrounding skin and lymph node basins prior to re-excision (Table 93.9).

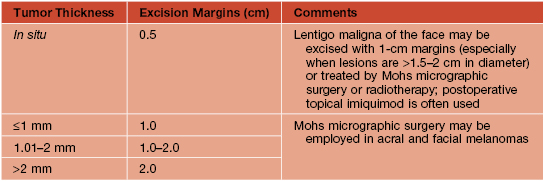

Table 93.9

Surgical treatment of primary cutaneous melanoma.

Evidence from available randomized trials is insufficient to address the optimal margins for the excision of primary cutaneous melanoma, but multiple expert international committees have produced fairly consistent guidelines, as summarized here. Of note, further investigative efforts will likely alter the standards of care over time.

Adapted from Sladden MJ, et al. Surgical excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2009;(4):CD004855.

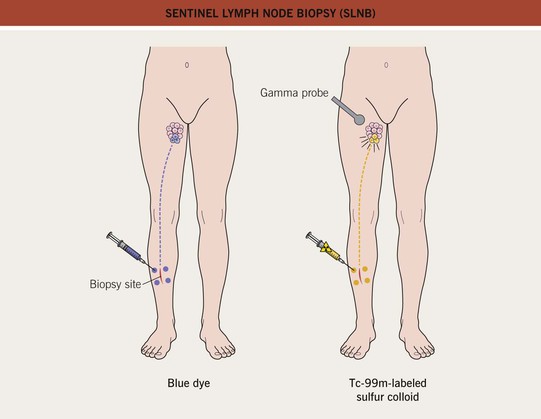

• Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB):

– Indications for consideration of SLNB: CM with T ≥1 mm and no clinically involved regional lymph nodes or distant metastases; selected patients with T <1 mm but with ulceration and/or mitoses ≥1/mm2.

– Typically performed at the time of re-excision (Fig. 93.16).

Fig. 93.16 Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB). Identification of the sentinel node(s) using the injection of blue dye, technetium-99m-labeled sulfur colloid, or both. Re-excision is performed after the injections. Redrawn from Olhoffer IH and Bolognia JL. What’s new in the treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Semin. Cutan. Med. Surg. 1998;17(2):96–107.

– Advantages: provides additional diagnostic and staging information; allows for entry into clinical trials.

– Disadvantages: can cause lymphedema; expensive; usually requires general anesthesia.

• Imaging studies for identification of metastases include: ultrasound of lymph node basins; CT scan of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis or PET scan in high-risk patients; and if symptoms, cranial MRI; serum LDH is measured serially as it influences prognosis (see Table 93.7).

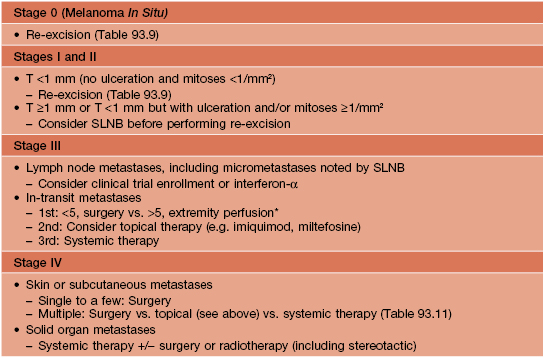

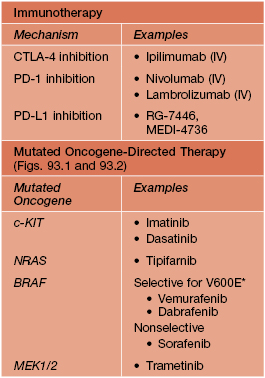

• Additional Rx is outlined in Tables 93.10 and 93.11.

Table 93.10

General guidelines for treatment of cutaneous melanoma (CM) based on stage at diagnosis, in addition to re-excision of the primary CM.

* Should be performed as part of a controlled study.

SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Table 93.11

Drugs recently approved or in clinical development for unresectable or metastatic melanoma.

With the discovery of genetic mutations that lead to dysfunction of signal transduction pathways, targeted therapies are being developed.

* Of melanomas with BRAF mutations, at least ~80% lead to an amino acid change at position 600, most commonly glutamic acid (E) substitutes for valine (V); can also be V600D or V600K.

IV, intravenous

• A melanoma patient worksheet can help organize all of this information for both the patient and the clinician (see Appendix).

Follow-Up

• Primary objectives include identification of potentially curable local recurrences (~4% of patients; Fig. 93.17) or regional metastases (e.g. in transit, lymph node; Fig. 93.18) and to identify second primary CMs (up to 5% of patients).

Fig. 93.17 Local recurrence of cutaneous melanoma. A Recurrent lentigo maligna along upper lateral margin of the excision on the chin; inked lesion on central upper lip is an actinic keratosis. B Recurrent, in situ acral lentiginous melanoma at the 10 o’clock position on the split-thickness skin graft. C Amelanotic nodular recurrence of a desmoplastic melanoma within the skin graft. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 93.18 In-transit metastases of melanoma. A Multiple pink papulonodules along the lymphatics were treated with intralesional low-dose IL-2 for 6 weeks. B Complete remission after 1 year, which persisted during the follow-up period of 7 years. Courtesy, Claus Garbe, MD.

• Although up to 10% of patients with CM have familial melanoma, mutations have been detected in a limited number of high-penetrance genes (e.g. CDKN2A >> CDK4); when a patient with CM has multiple primaries, ≥2 family members with CM, and/or a family history of pancreatic cancer, consideration of genetic counseling should be discussed.

For further information see Ch. 113. From Dermatology, Third Edition.