Chapter 6 Critical care nursing

NATURE AND FUNCTION OF CRITICAL CARE NURSING

Nurses are the one round-the-clock constant for critically ill patients and their families, acting as the ‘glue’ that holds the critical care service together. Nurses ensure safety and provide continuity and fine-tuning, coordinating and communicating all the elements of treatment and care needed by the patient.

Skilled critical care nurses provide:

There is inevitably an emphasis on technology in the intensive care unit (ICU), and nurses must be technically competent. However, treatments should be administered with an understanding of the essential human elements of care. ICU patients report that such care is often missing: one described his experience as ‘rooted in the minute analysis of charts and the balancing of chemicals, not so much in the warmth of human contact’.3

Patients are not usually able to control what happens to them during the first phases of critical illness, but seek to reassert their autonomy as they begin to recover, e.g. when weaning from ventilation or with the transition to lower levels of care. Critical care nurses can enable patients to have a say in the management of these processes while still ensuring safe progression through different stages of treatment. Studies highlight the value of connecting with patients both psychologically and physically,4 and that patient-centred care and emotional support can be lost when the nursing resource is reduced.5 Fundamental care (e.g. personal cleansing, protection of tissue integrity, prevention of infection) is also generally undertaken or supervised by nurses. Other important functions (e.g. chest physiotherapy, mobilisation, delivery of nutrition) may be managed by other specialists, but it is nurses who integrate these treatments into a complete package of care.

A SYSTEMATIC APPROACH TO CARE

Further detail may then be gained from review of:

More sophisticated models can be used to frame a wider impression of the patient and to reflect a particular philosophy or approach to nursing. For example, the Roy model7 expresses a view of nursing as a vehicle for enabling adaptive adjustments to any dysfunction. The model prompts analysis of both immediate and other contributing influences in a systematic consideration of oxygenation, nutrition, elimination, activity and rest, protective mechanisms, sensory function, fluid, electrolyte and acid–base balance, neurological and endocrine function, as well as the patient’s self-concept, role-mastery and psychosocial interdependence.7 Such an approach has a commendable breadth of vision, but may be too complex for the novice. Articulation of patient problems may be aided by the use of validated nursing diagnoses, as developed in North America. This system provides definitions and recommended nursing responses for many problems, and specifies appropriate outcome measures. What is most important is that any system used gives unambiguous definitions of patient problems and a clear statement of specific, measurable therapeutic goals.

NURSING AND PATIENT SAFETY

Inadequate nurse staffing is linked to increases in adverse events, patient morbidity and mortality. Significant numbers of patients suffer serious harm caused by errors in clinical practice, but nurses prevent many more incidents by intercepting and mitigating errors made by other professionals.8 Direct observation and patient care remain key to patient safety:9 it has been calculated that at least seven nurses need to be employed for each patient if a nursing presence is required continually 24 hours a day.1 No particular system of critical care nursing has been shown to be definitively superior to others,9 but ensuring appropriate nursing numbers, skills and experience to meet patient need is a gold standard of care10 (see Staffing the critical care unit, below).

EVOLVING ROLES OF CRITICAL CARE NURSES

Critical care nurses’ range of practice has evolved rapidly with progress in technology and with changes in the working of interdisciplinary team colleagues. The benefits of developing new skills must be balanced against ensuring the maintenance of fundamental patient care.11 There remains a large variation in the array of tasks undertaken by nurses in critical care, with invasive procedures and drug prescriptions still usually performed by doctors. However, from 2006 qualified nurse (and pharmacist) prescribers in the UK have been enabled – in theory at least – to prescribe licensed medicines for the whole range of medical conditions. Nurse prescribing is not as yet a widespread phenomenon in critical care, but may become a routine part of practice in the future.

Critical care nurses also have a large and developing role in decision-making regarding the ongoing adjustment, titration and troubleshooting of such key treatments as ventilation, fluid and inotrope administration, and renal replacement therapy. The use of less invasive techniques (e.g. transoesophageal Doppler ultrasonography for cardiac output estimation) means that it is possible for nurses to institute relatively sophisticated monitoring and administer appropriate therapies for restoration of homeostasis. There is evidence that nurses can achieve good outcomes in these areas, especially with the use of clinical guidelines and protocols; for example, by reducing the time to wean respiratory support.12 This indicates that further development of protocols, guidelines, care pathways and the like can be used to enhance the nursing contribution to critical care.

NEW NURSING ROLES IN CRITICAL CARE

Medical and nursing staffing in the ICU is an ongoing problem in many countries. This has led to the development of various new ways of working to deliver both fundamental and more sophisticated modes of care.13 New nursing roles include those that essentially substitute for medical roles, as well as those that retain a nursing focus and aim to fill gaps in health care with nursing practice rather than medical care. For example, the UK has designated a relatively small number of nurse consultant posts in all areas of health care, with the largest proportion in critical care, particularly in outreach roles. These are advanced practitioners focusing primarily on clinical practice but also required to demonstrate professional leadership and consultancy, development of appropriate education and training, macrolevel practice and service development, research and evaluation.14

Other sorts of non-nursing staff are increasingly being used to deliver what has been seen as basic nursing care (e.g. oral and ocular care, recording of vital signs), in order to support trained nurses and enable them to concentrate on more advanced practices.15 Nursing shortages may make such developments inevitable in some areas, but it is imperative that nurses continue to ensure best outcomes for patients with proper arrangements for training, support and working systems.

CRITICAL CARE NURSING BEYOND THE ICU: CRITICAL CARE OUTREACH

Around the world, general wards are required to manage an increasing throughput of patients who are, on average, older than before, with more complex, chronic diseases, and more acute and critical illness. Review of admissions to ICU from general wards shows that many patients experience substandard care before transfer.16 Various factors are implicated, including lack of knowledge and failure to appreciate clinical urgency and to seek advice, compounded by poor organisation, breakdown in communication and inadequate supervision.

These issues are problems for the whole interdisciplinary team, but the nursing contribution is significant. It is nurses who record or supervise the recording of vital signs, suggesting that there is often poor understanding of the seriousness of such indicators, or failures to communicate effectively with medical staff, or difficulty in ensuring that appropriate treatment is prescribed and administered. Nurse-led outreach teams can support ward staff caring for at-risk and deteriorating patients, and facilitate transfer to intensive care when appropriate17 (see Chapter 2). They can also support the care of patients on wards after discharge from ICU, and after discharge from the hospital (see Chapter 8). Potential problems with these approaches include a loss of specialist critical care staff from the ICU, and being sure that outreach teams have the necessary skills to manage high-risk patients in less well-equipped areas, particularly when there are limitations placed on nurses prescribing and administering treatments.

NURSING IN THE INTERDISCIPLINARY TEAM

Effective critical care is based on interdisciplinary teamwork, with:

QUALITY OF CARE

Robust systems of audit are the foundation of quality care. Various measures have been suggested as indicators of the effectiveness of nursing structures, processes and outcomes, e.g. pressure ulcer prevalence, nosocomial infection rates and patient satisfaction. Although nurses should take responsibility for the care that they deliver, there are few, if any, nursing activities that can be considered entirely separately from other variables that influence patient outcomes. Furthermore, there are few, if any, medical interventions that are unaffected by nursing care. Rather, quality care depends on a collective interdisciplinary commitment to continuous improvement.19 This interdependence of different critical care personnel was illustrated in a multicentre investigation where interaction and communication between team members were more significant predictors of patient mortality than the therapies used or the status of the institution.20

STAFFING THE CRITICAL CARE UNIT1

STRESS MANAGEMENT AND MOTIVATION

The ICU can be extremely stressful, demanding considerable cognitive, affective and psychomotor effort. Supervisory arrangements and feedback mechanisms should be in place to alleviate such demands, and enable prompt recognition of staff who are having difficulties at work. Regular individual performance reviews and formulation of development plans provide positive assurance and encouragement and can identify individuals’ personal requirements, such as educational needs. They also provide an opportunity to identify poor practice that can then be rectified in a constructive manner. Study of human resource practices in acute hospitals has found a strong association between the quantity and quality of staff appraisal and patient mortality.21 Organisations that emphasise training and team-working also have better outcomes.21 Developing nurses’ critical thinking and decision-making skills is important for effective working. The nurse manager should provide a system that facilitates such training.

NURSE EDUCATION

Critical care nurses generally enjoy well-established educational programmes, although there is variability in the content and quality of such training. Nurses usually wish to gain formal academic credentials, and there is a role for study of relevant philosophy, nursing theory and research methods. However, there is a fundamental requirement for learning that focuses on clinical practice issues and problem-solving that benefits patients.22 It is also clear that there should be more widespread deployment of critical care nursing skills. These imperatives drive a need to produce unambiguous statements about the standards necessary for proper nursing assessment and nursing management of critically ill patients.

Summarised examples of competencies for critical care nurses might include the following:23

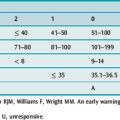

Various frameworks to identify different levels of performance have been developed, e.g. based on Benner’s hierarchy4 (Table 6.1). These can be used to mark progression to particular standards in core skills.

CRITICAL CARE NURSING RESEARCH

REVIEWING RESEARCH

UNDERTAKING A RESEARCH PROJECT

STAGE 2: GATHER RELEVANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION

It is important to collect information that enables an understanding of the issues under investigation, and helps justify performing the study. Hospital libraries are useful, not least because there may be staff who can give advice about the project. Indexes for journals and books are in print and computer-based formats, with databases and texts also available through the internet. A good starting point is Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com/). This uses a broad approach to locating articles in searches across many disciplines and sources. More specific medical/nursing websites include:

The researcher must also evaluate the quality of the information gathered. Different types of research are traditionally considered to have different weights, e.g. results obtained from randomised controlled trials are considered to be high-grade evidence, whereas observational studies are deemed less useful.25 This hierarchy is not always applicable and may devalue some sorts of valuable work, but it does emphasise the need to examine critically the credibility of research.

STAGE 3: DESIGN A METHOD THAT:

STAGE 6: PRESENT AND EXPLAIN THE DATA

Prsentation can take many forms, but it is always necessary to set out the question asked, to describe the research method so that it is clear what was done, to illustrate the results and their analysis and to present the key findings and conclusions. The conclusions should follow from the analysis, without inappropriate extrapolations. Any applications to clinical practice should be highlighted. The report must be presented succinctly and in a constructive manner, but with any shortcomings or problems in the study discussed. The goal is that the reader can understand the methodology and how the results were interpreted, while acknowledging any limitations of the work.

RESEARCH ETHICS

The practitioner must always consider the ethical issues associated with conducting research: in many countries it is a criminal offence to undertake medical research without ethical approval. The researcher generally needs to submit a detailed application document for approval to an ethics committee. There are local differences in the process of obtaining ethical approval for research on humans, but most systems incorporate the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (see the World Medical Association website at http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm).

An ethics committee is usually made up of professional and lay members attached to hospitals or universities. The committee looks beyond the stated necessity and significance of the proposed research to evaluate a range of matters particular to the patients who may be involved, and to aspects of the study design. Some of these issues are summarised in Table 6.2.

Table 6.2 Issues for consideration in the review of research proposals

| Particular to the patient/research subject | Particular to study design/integrity |

|---|---|

|

• The degree of inconvenience to the patient/research subject (or associated persons, e.g. patients’ relatives)

|

1 Royal College of Nursing. Guidelines for Nurse Staffing in Critical Care. London: Royal College of Nursing, 2003.

2 Chinn P, Kramer M. Integrated Knowledge Development in Nursing. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 2003.

3 Watt B. Patient: The True Story of a Rare Illness. London: Penguin, 1996.

4 Benner P. From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Addison-Wesley: Menlo Park, 1984.

5 Ball C, McElligot M. Realising the potential of critical care nurses: an exploratory study of the factors that affect and comprise the nursing contribution to the recovery of critically ill patients. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 2003;19:226-238.

6 Hillman K, Bishop G, Flabouris A. Patient examination in the intensive care unit. In Yearbook of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 2002. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2002.

7 Roy C, Andrews H. The Roy Adaptation Model. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1999.

8 Rothschild J, Hurley A, Landrigan C, et al. Recovery from medical errors: the critical care nursing safety net. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Safe. 2006;32:63-72.

9 Coombs M, Lattimer V. Safety, effectiveness and costs of different models of organising care for critically ill patients: literature review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2007;44:115-129.

10 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. AACN Standards for Establishing and Sustaining Healthy Work Environments. Aliso Viejo, CA: American Association of Critical Care-Nurses, 2005.

11 Mullally S. Improving the quality of clinical practice. Nurs Ethics. 2000;7:531-532.

12 Kollef M, Shiparo S, Silver P, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of protocol directed versus physician directed weaning from mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:567-574.

13 Scholes J, Furlong S, Vaughan B. New roles in practice: charting three typologies of role innovation. Nurs Crit Care. 1999;4:268-275.

14 NHS Executive. Health Service Circular 1999/217. Nurse, Midwife and Health Visitor Consultants. Leeds: NHS Executive, 1999.

15 Hind M, Jackson D, Andrews C, et al. Health care support workers in the critical care setting. Nurs Crit Care. 2000;5:31-39.

16 Cullinane M, Findlay G, Hargraves C, et al. An Acute Problem? A Report of the National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death. London: NCEPOD, 2005.

17 Watson W, Mozley C, Cope J, et al. Implementing a nurse-led critical care outreach service in an acute hospital. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:105-110.

18 Department of Health-Emergency Care Team. Quality Critical Care: Beyond ‘Comprehensive Critical Care’: A Report by the Critical Care Stakeholder Forum. London: Department of Health-Emergency Care Team, 2005.

19 Curtis J, Cook D, Wall R, et al. Intensive care unit quality improvement: a ‘how-to’ guide for the interdisciplinary team. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:211-218.

20 Tarnow-Mordi W, Hau C, Warden A, et al. Hospital mortality in relation to staff workload: a 4-year study in an adult intensive care unit. Lancet. 2000;356:185-189.

21 West M, Borrill C, Dawson J, et al. The link between the management of employees and patient mortality in acute hospitals. Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2002;13:1299-1310.

22 Wigens L, Westwood S. Issues surrounding educational preparation for intensive care nursing in the 21st century. Intens Crit Care Nurs. 2000;16:221-227.

23 SW London Critical Care Nursing Curriculum Planning Group. Critical Care Competencies. London: Kingston University and St George’s Hospital Medical School Faculty of Healthcare Sciences, 2002.

24 Wilcock P, Brown G, Bateson J, et al. Using patient stories to inspire quality improvement within the NHS Modernization Agency collaborative programmes. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12:422-430.

25 Concato J, Shah N, Horwitz R. Randomized, controlled trials, observational studies, and the hierarchy of research designs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1887-1892.