10 Cranial Nerves XI and XII

Accessory and Hypoglossal

Cranial Nerve XI: The Spinal Accessory Nerve

Anatomy

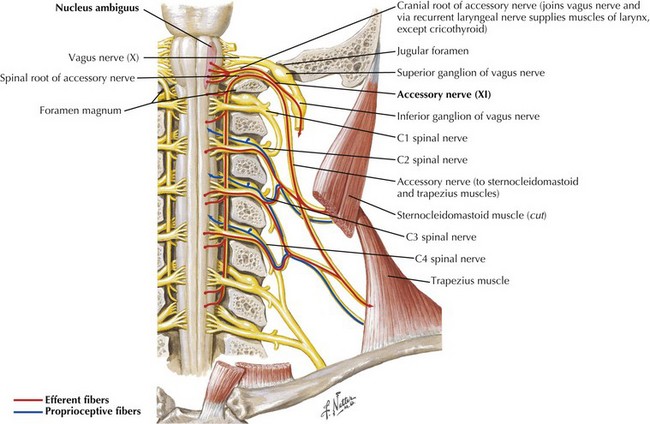

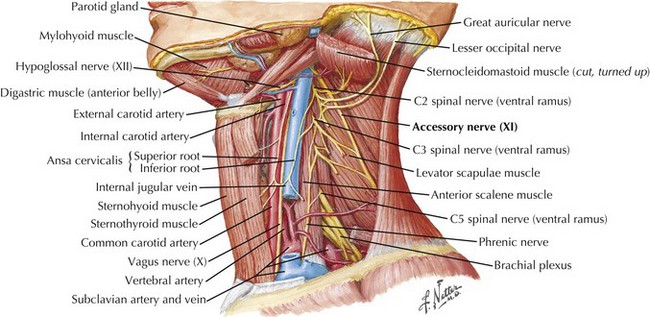

The SAN is primarily a motor nerve innervating the SCM and trapezius muscles in the neck and back (Fig. 10-1). In contrast to the other cranial nerves, its lower motor neuron cell bodies are located primarily within the spinal cord. The accessory nucleus is a cell column within the lateral anterior gray column of the upper five or six cervical spinal cord segments. Proximally it lies nearly in line with the nucleus ambiguus and caudally within the dorsolateral ventral horn. Originating from the accessory nucleus, the rootlets emerge from the cord and unite to form the trunk of CN-XI. This extends rostrally through the foramen magnum into the posterior cranial fossa. Intracranially, it accompanies the caudal fibers of the vagus nerve (CN-X) exiting the skull through the jugular foramen. The SAN then descends in close proximity to the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein (Fig. 10-2).

The supranuclear innervation of the CN-XI nuclei is still a matter of debate. Although the trapezius muscle is innervated from the opposite hemisphere, there is some question as to whether the supranuclear innervation of the SCM is also contralateral. One standard neuroanatomy text, Brodal 1998, states that with clinical corticobulbar lesions there is paresis of the contralateral SCM as well as the trapezius. Others note, based on intracarotid Amytal injections, that the SCM is innervated predominantly from the ipsilateral hemisphere. Suffice it to say that the most proximal and midline musculature can be activated bilaterally. Therefore, one needs to be circumspect when attempting to lateralize the source of unilateral SCM weakness.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Approach

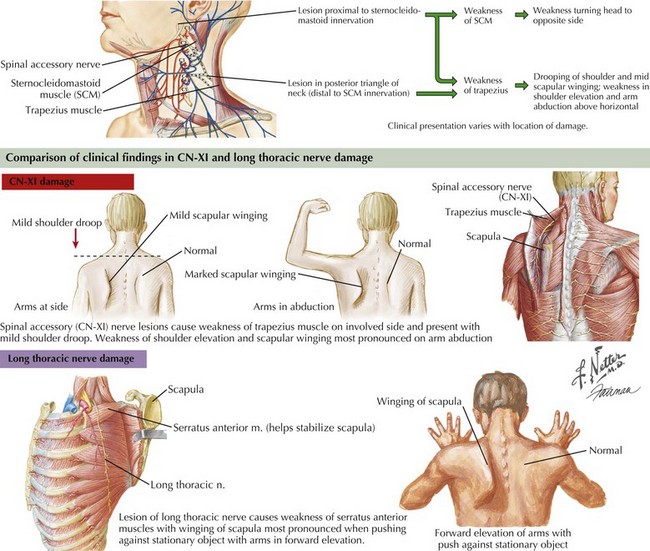

Involvement of the trapezius manifests as drooping of the shoulder and mild scapular winging away from the chest wall with slight lateral displacement. Weakness in shoulder elevation and arm abduction above horizontal is typical. Winging is apparent with arms hanging along the trunk, and becomes accentuated when patients abduct the arms. In contrast, scapular winging from serratus anterior weakness due to long thoracic nerve palsy is most prominent on forward elevation of the arms (Fig. 10-3).

Cranial Nerve XII: Hypoglossal

Anatomy

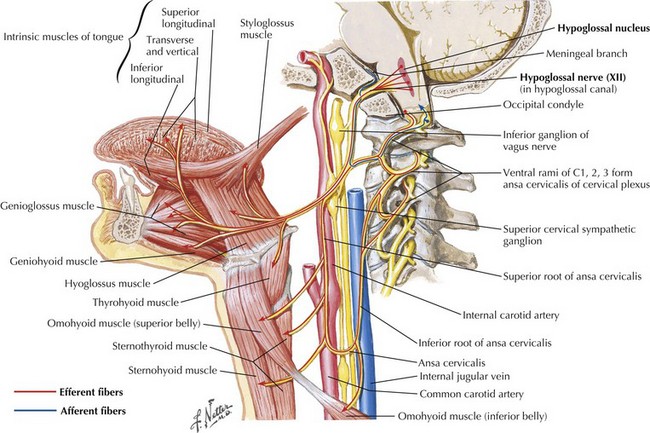

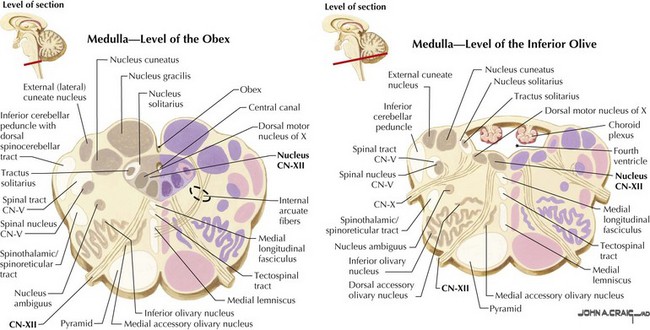

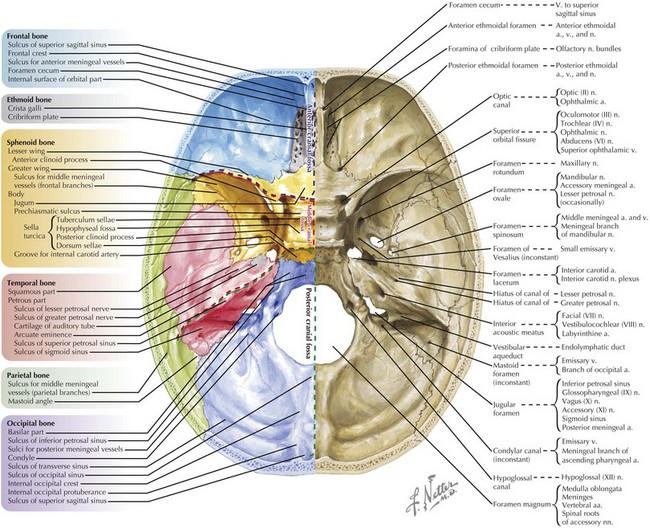

CN-XII carries motor fibers that supply all intrinsic and most extrinsic tongue muscles, that is, the hyoglossus, styloglossus, genioglossus, and geniohyoid (Fig. 10-4). Its fibers originate from the hypoglossal nucleus beneath the floor of the fourth ventricle (Fig. 10-5). In its intramedullary course, CN-XII axons pass ventrally and lateral to the medial lemniscus emerging from the medulla in the ventrolateral sulcus between the olive and the pyramid. The rootlets unite to form CN-XII, which exits the skull through the hypoglossal foramen adjacent to the foramen magnum within the posterior cranial fossa (Fig. 10-6).

After exiting the skull, CN-XII runs medial to CN-IX, -X, and -XI. It continues between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein, and deep into the posterior belly of the digastric muscle. It then loops anteriorly, coursing on the lateral surface of the hyoglossus muscle, and later, it divides to supply the intrinsic and extrinsic muscles of the ipsilateral tongue (see Fig. 10-4).

Clinical Presentation

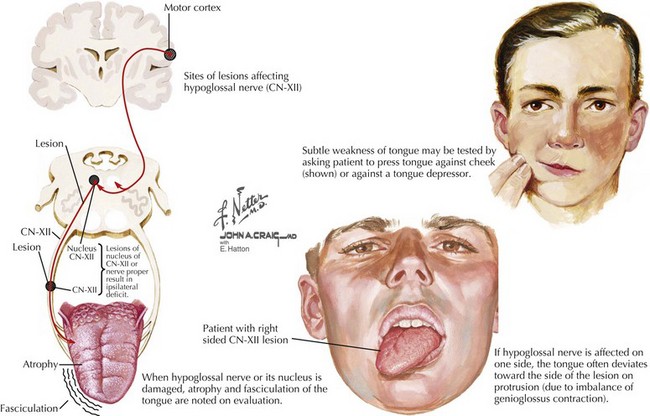

Straight protrusion of the tongue is accomplished by balanced action of both genioglossus muscles. Therefore, bilateral CN-XII lesions impair tongue protrusion as well as up, down, and side-to-side movements. This in turn causes dysarthria and swallowing difficulties. A unilateral lower motor neuron hypoglossal nerve lesion causes the tongue to deviate toward the side of the lesion when the patient attempts to protrude the tongue forwards. Typically, these lesions are also associated with atrophy, fasciculations, and increased furrowing of the ipsilateral side of the tongue (Fig. 10-7). Swallowing and/or speech dysfunction may not be present early on. Fine quivering or flickering movements are normally seen in healthy patients asked to hold the tongue protruded for more than a few seconds, and these may occasionally be confused with true fasciculations. The most reliable way to evaluate for fasciculations is to keep the tongue at rest on the floor of the mouth. Sometimes, fasciculations may be enhanced by stroking the lateral aspect of the resting tongue with a standard wooden tongue blade. A unilateral upper motor neuron lesion may on occasion result in deviation of the tongue; however, this is contralateral to the central lesion, and there is never any accompanying atrophy or fasciculations. In certain disorders, particularly amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, both upper and lower motor neuron components may be present, with the combination leading to some initial diagnostic confusion if this area is the first to become clinically affected.

Differential Diagnosis

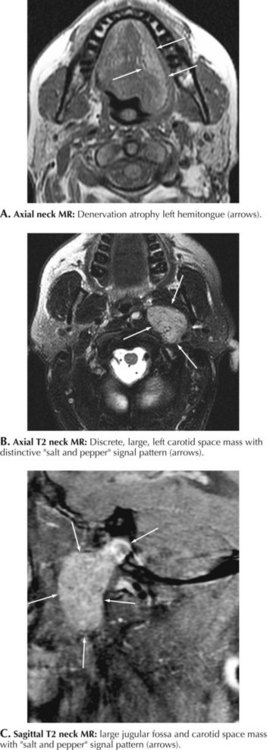

The close spatial relation between the hypoglossal nerve and the carotid artery makes this nerve vulnerable to primary carotid pathology within the neck. Very rarely, dissection of the internal carotid artery is accompanied by a CN-XII neuropathy, most likely related to nerve compression by the increased circumference of the dissected vessel. Occasionally, an iatrogenic hypoglossal neuropathy occurs subsequent to a carotid endarterectomy or other types of neck surgery. A nasopharyngeal cancer may damage CN-XII along its intracranial course or within the neck per se; this is usually in conjunction with involvement of other cranial nerves. Glomus jugulare tumor is a rare hypervascular malignancy that arises from the paraganglionic tissue at the jugular foramen and can compress CN-XII either at the base of the brain or conceivably within the neck (Fig. 10-8A–C). Similar to other cranial nerves, the CN-XII may also be affected by radiation therapy and neck trauma. Most uncommonly, the hypoglossal nerve is affected as part of two primary demyelinating peripheral nerve syndromes, namely, hereditary neuropathy with liability to pressure palsies (HNPP) or a variant of chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), the Lewis–Sumner syndrome.

Berger PS, Bataini JP. Radiation-induced cranial nerve palsy. Cancer. 1977;40:152-155. This classic paper describes 25 patients with cranial nerve palsies following radiation therapy for head and neck cancer; the spinal accessory nerve was involved in 5 patients

Brodal P. The Central Nervous System, Structure and Function, 2nd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998. p. 452-453

Brown H. Anatomy of the spinal accessory nerve plexus: relevance to head and neck cancer and atherosclerosis. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2002;227:570-578. This article provides a detailed review of surgical anatomy of spinal accessory nerve and its relationship to cervical and brachial plexus as well as other neck structures. Special attention is given to the nerve’s vascular supply

DeToledo JC, Dow R. Sternomastoid function during hemispheric suppression by Amytal: insights into inputs to the spinal accessory nerve nucleus. Mov Disord. 1998;13:809-812. Weakness of the SCM ipsilateral to the Amytal carotid injection argues that ipsilateral hemisphere is the one more involved in supranuclear innervation of the SCM

Friedenberg SM, Zimprich T, Harper CM. The natural history of long thoracic and spinal accessory neuropathies. Muscle Nerve. 2002;25:535-539. This retrospective review of 56 cases seen at Mayo Clinic over 22 years provides insight into the natural history, outcome predictors, and role of electrophysiology in spinal accessory nerve lesions

Greenberg HS, Deck MD, Vikram B, et al. Metastasis to the base of the skull: clinical findings in 43 patients. Neurology. 1981;31(5):530-537. In this classic paper, the combination of occipital headache and unilateral hypoglossal palsy due to a skull base metastasis was first described as the occipital condyle syndrome

Gutrecht JA, Jones HR. Bilateral hypoglossal nerve injury after bilateral carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 1988;19:261-262. This instructive case points out the often dramatic difference between the clinical presentation of bilateral versus unilateral hypoglossal neuropathy

Keane JR. Twelfth-nerve palsy. Analysis of 100 cases. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:561-566. In this large series, nearly half of the cases of hypoglossal neuropathy were due to a neoplasm

Kim DH, Cho YJ, Tiel RL, et al. Surgical outcomes of 111 spinal accessory nerve injuries. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1106-1112. This is a retrospective review of injury mechanisms, operative techniques and surgical outcomes of 111 cases of spinal accessory neuropathy that underwent surgical repair

Wesselmann U, Reich SG. The dynias. Semin Neurol. 1996;16:63-74. In this review of “dynias,” authors discuss the controversial syndrome of glossodynia