6 Cranial Nerve V

Trigeminal

Anatomy

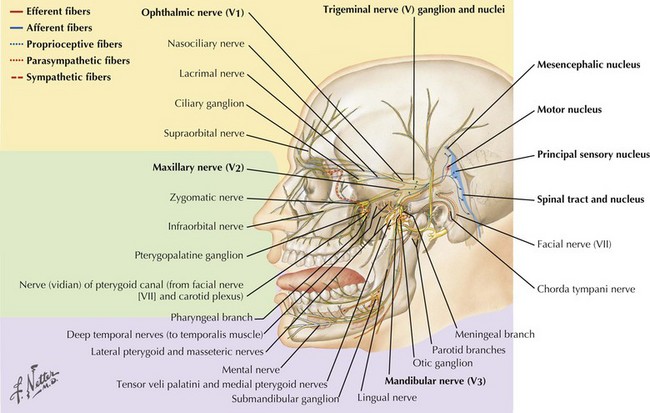

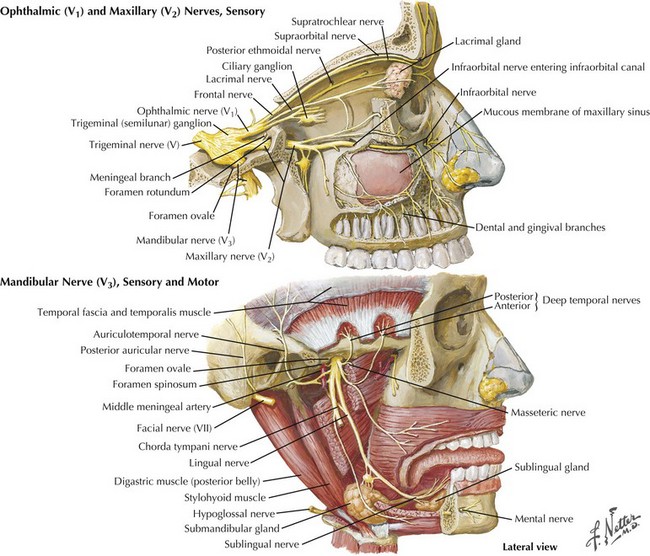

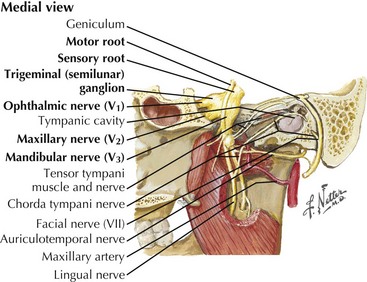

The trigeminal cranial nerve (CN-V) has three major divisions: ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular (Figs. 6-1 and 6-2). CN-V is the major sensory nerve of the face, mouth, and nasal cavity. It also supplies motor and proprioceptive fibers to the muscles of mastication. The trigeminal nerve sensory and motor roots are derived from a large sensory and smaller motor nucleus within the pons. These roots converge to emerge at the midlateral pons, then continue toward the trigeminal (Gasserian) ganglion at the base of the middle cranial fossa. General sensory fibers are derived from their cell bodies of origin within this ganglion. Distal to the trigeminal ganglion, three sensory divisions respectively exit the skull through the superior orbital fissure, foramen rotundum, and foramen ovale. The motor component passes through the trigeminal ganglion into the mandibular division.

CN-V Nuclei

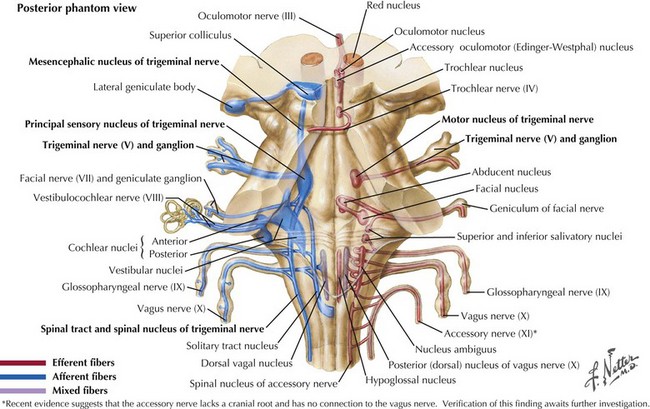

The sensory nucleus is the largest of the trigeminal pontine complex. This begins rostrally within the midbrain, and extends caudally through the pons and medulla into the second segment of the cervical spinal cord (Fig. 6-3). It is subdivided into three portions: (1) the spinal tract nucleus primarily dedicated to pain and temperature fibers; (2) the principal sensory nucleus, the pontine trigeminal portion, which primarily receives tactile stimuli and, therefore, principally subserves light touch; (3) the mesencephalic sensory nucleus, which contains cell bodies of sensory fibers carrying proprioceptive information from the masticatory muscles. Lastly, there is a motor nucleus located within the pons medial to the large sensory nucleus.

Principal Sensory Component

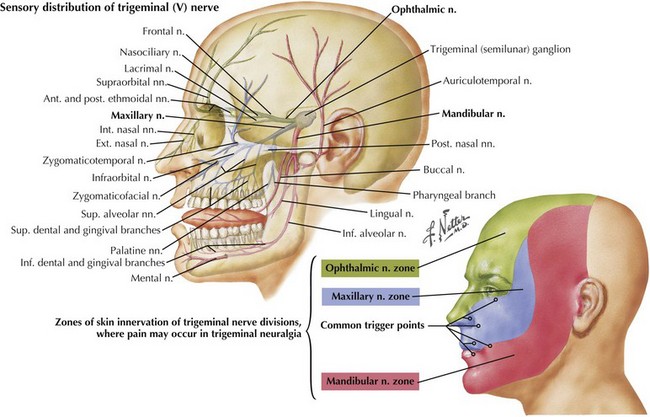

This component of CN-V conveys general sensation from the facial skin and scalp to the top of the head, tragus of the ear, and anterior wall of the external auditory meatus (Fig. 6-4). Also, it provides general sensation from the mouth, including the tongue and teeth, nasal and paranasal sinuses, and meninges lining the anterior and middle cranial fossae.

Trigeminal (Gasserian, Semilunar) Ganglion

The cell bodies of almost all sensory CN-V fibers are located within the trigeminal ganglion (Fig. 6-5). This is contained within a skull-based depression, the Meckel cave, that is located in the floor of the middle cranial fossa. Central processes of neuronal cell bodies constitute the large sensory root that enters the pons and projects into the pontine trigeminal main sensory nucleus and spinal tract nucleus. The peripheral processes of this nerve divide into the three sensory divisions that exit the skull through the superior orbital fissure, the foramen rotundum, and the foramen ovale.

CN-V Lesions

Clinical Presentation and Diagnostic Approach

Trigeminal neuralgia is the most common fifth cranial nerve disorder as discussed in Primary and Secondary Headache, Chapter 11. In contrast, a primary trigeminal neuropathy, as illustrated in this chapter’s vignette, is very uncommon.

Differential Diagnosis

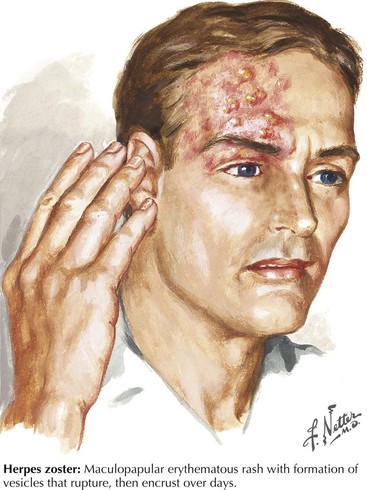

In the Western world, Herpes zoster is the most common infectious cause of a trigeminal neuropathy (Fig. 6-6). Herpes zoster ophthalmicus occurs when latent varicella zoster virus infection within the trigeminal ganglion becomes reactivated, almost always affecting the ophthalmic division. However, very rarely, the maxillary or mandibular divisions may be primarily affected. Most patients present with a characteristic periorbital vesicular rash and severe neuralgic pain within the ophthalmic division (see Fig. 6-6). Similar to other herpes zoster syndromes, the pain may precede the eruption of cutaneous lesions. Permanent visual impairment is the most serious outcome of ophthalmic zoster infection. Antiviral agents such as acyclovir are the main therapy. Corticosteroid eyedrops are shown to decrease pain and hasten corneal healing and are sometimes prescribed by ophthalmologists if there are no other ocular or systemic diseases that might contraindicate their use. Rarely, an ipsilateral middle cerebral artery infarction may subsequently develop in these patients as the virus travels within the trigeminal nucleus and affects the adjacent intracavernous portion of the carotid artery or its branches with a granulomatous angiitis of the brain. CSF varicella zoster virus antibodies are frequently found, and antiviral treatment is felt to be helpful.

Worldwide, leprosy or Hansen disease is a more common cause of CN-V neuropathy. This primarily occurs in economically depressed countries. It generally affects the coolest areas of the skin. Thus, if sensory loss is confined to the tip of the nose or the pinna of the ear, Hansen disease is a primary consideration (Box 6-1).

Box 6-1 Differential Diagnosis of CN-V Lesion Origin

Brainstem: stroke, brainstem gliomas, multiple sclerosis, or syringobulbia

Skull base lesions: metastasis, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, lymphoma, basilar meningitis

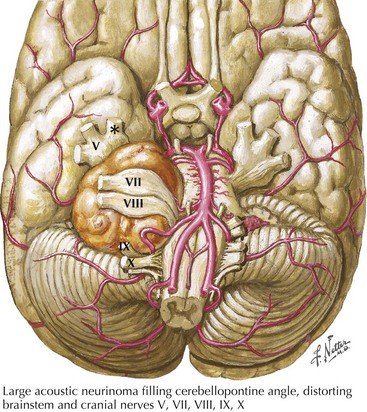

Cerebellopontine angle tumors, typically acoustic neurinomas arising form CN-VIII (Fig. 6-7), may enlarge and compress the trigeminal sensory root and lead to facial numbness or pain with subsequent ipsilateral loss of the corneal reflex. Other neoplasms include meningiomas, epidermoids, lymphomas, hemangioblastomas, gangliocytomas, chondromas, and sarcomas. Similarly, certain skull base tumors, such as nasopharyngeal carcinoma, salivary gland adenocarcinoma, and metastatic disease, may invade various trigeminal divisions. The numb chin syndrome consists of unilateral numbness of the chin and adjacent lower lip. Although seemingly harmless, it is usually an ominous sign of primary or metastatic cancer involving the mandible, skull base, or leptomeninges. Lymphoproliferative malignancies and metastatic breast cancer are the most common etiologies.

Chan WO, Madge S, Dodd TJ, et al. Multiple cranial nerve palsies as a result of perineural invasion by squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2008 Aug;69(8):476-477.

Elias WJ, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia and other neuropathic pain syndromes of the head and face. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:115-124.

Hughes RAC. Diseases of the fifth cranial nerve. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, Griffin JW, et al, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1993:801-817.

Loeser JD. Tic douloureux. Pain Res Manag. 2001;6:156-165.

Maillefert JF, Gazet-Maillefert MP, Tavernier C, et al. Numb chin syndrome. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67:86-93.

Nager GT. Neurinomas of the trigeminal nerve. Am J Otolaryngol. 1984;5:301-333.

Rosenbaum R. Neuromuscular complications of connective tissue diseases. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:154-169.

Rowe JG, Radatz MW, Walton L, et al. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery for unilateral acoustic neuromas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2003;74:1536-1542.

Severson EA, Baratz KH, Hodge DO, et al. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus in Olmsted County, Minnesota: have systemic antivirals made a difference? Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:386-390.

Starr CE, Pavan-Langston D. Varicella-zoster virus: mechanisms of pathogenicity and corneal disease. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 2002;15:7-15.

Sweeney PJ, Hanson MR. The cranial neuropathies. In: Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, et al, editors. Neurology in Clinical Practice: Principles of Diagnosis and Management. 2nd ed. Boston, Mass: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1996:1721-1732.

Zhu JJ, Padillo O, Duff J, et al. Cavernous sinus and leptomeningeal metastases arising from a squamous cell carcinoma of the face: case report. Neurosurgery. 2004 Feb;54(2):492-498. discussion 498-499