3 Cranial Nerve I

Olfactory

Dysfunction of the olfactory nerve is quite rare, occurring in certain very select circumstances. Examination of olfactory function is not routinely pursued during the average neurologic evaluation (Chapter 1). However, in clinical settings such as in the above vignette, it is essential to routinely evaluate olfactory function by asking the patient to identify a few familiar odors such as coffee, perfumes, tobacco, etc. On occasion, the patient may not be aware of or assign much importance to the loss of his or her smell sensation. This may be particularly true when there is a concomitant neurologic deficit as seen in occasional patients with potentially treatable olfactory groove meningiomas that also compromise frontal lobe function.

Anatomy

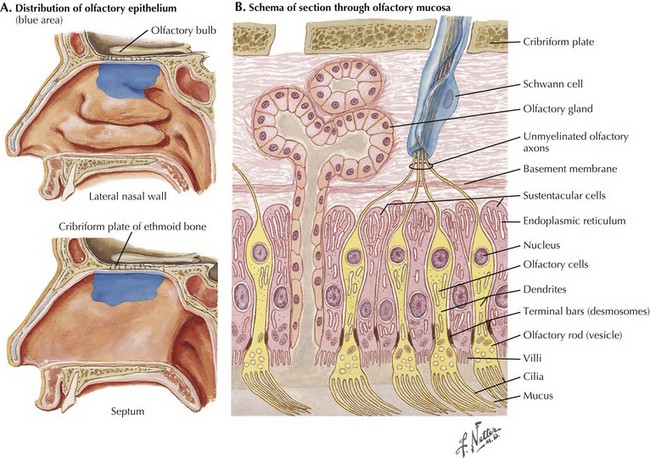

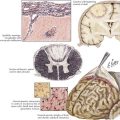

When identifying odors, humans rely on volatile substances entering their nasal cavity to excite receptors. Olfactory receptor cells are bipolar sensory neurons whose dendrites form a delicate sensory carpet on the superior aspect of the nasal cavity (Fig. 3-1). The thin, unmyelinated axons of the bipolar sensory cells collectively form the olfactory nerve. These travel through the cribriform plate into the olfactory bulb at the base of the fronto-orbital lobe. Within the bulb, CN-I fibers synapse with the dendrites of the large mitral cells, whose axons constitute the olfactory tract passing along the base of the frontal lobe and projecting directly into the primary olfactory cortex within the temporal lobe. In contrast to all other sensory modalities, olfactory sensation does not have a central processing site such as within the thalamic nuclei (Fig. 3-2). This direct pathway to the cerebral limbic structures may have had an important evolutionary function in lower animals and, later, primates.

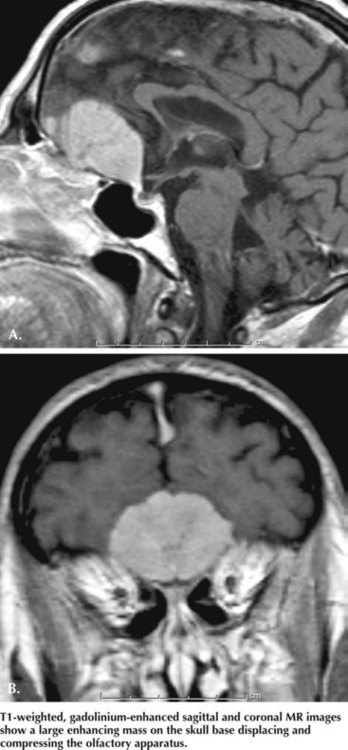

The human primary olfactory cortex includes the uncus, hippocampal gyrus, amygdaloid complex, and entorhinal cortex (Fig. 3-2). Cortical representation of smell is bilateral. Although most of the olfactory tract fibers supply the ipsilateral olfactory cortex, some fibers decussate in the anterior commissure and terminate in the opposite hemisphere. Consequently, a unilateral lesion distal to the decussation rarely produces any olfactory dysfunction.

Differential Diagnosis

Acquired Disorders

Olfactory groove meningiomas are quite infrequent; however, if these remain undiagnosed, these histologically benign tumors may still lead to significant morbidity unless treated early on. Usually meningiomas are slow growing; olfactory groove lesions comprise 8–18% of all intracranial meningiomas (Fig. 3-3). Although unilateral or bilateral olfactory dysfunction is thought to be their first symptom, very few patients present with just a disturbance in their sense of smell. This is probably because their slow and orderly growth leads to a very gradual decline in olfactory function. Furthermore, as most meningiomas are unilateral, they lead to unilateral anosmia and thus patients still retain olfactory function on the contralateral side. Thus, they are usually unaware of any focal loss. Consequently, most orbital meningiomas are not diagnosed until the tumor is large enough (e.g., >4 cm in diameter) to cause other symptoms resulting from pressure on the frontal lobes and optic tracts. These include headache, visual disturbances, personality changes, and memory impairment. Early diagnosis of olfactory groove meningiomas remains challenging. At times, the behavioral changes can be profound and may create a sense the patient is demented or mentally unbalanced.

. The Smell and Taste Center at The University of Pennsylvania. Available at http://www.med.upenn.edu/stc Accessed in June 2008

De Kruijk JR, Leffers P, Menheere PP, et al. Olfactory function after mild traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 2003;17:73-78. In this study, high prevalence of olfactory dysfunction was found in patients with mild traumatic injury

Dode C, Levilliers J, Dupont JM, et al. Loss-of-function mutations in FGFR1 cause autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:463-465. The authors expand our insight into molecular genetics of autosomal dominant Kallmann syndrome

Doty RL, Shaman P, Dann M. Development of University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test. Physiol Behav. 1984;32:489-502. Authors describe development of the first standardized olfactory test battery (UPSIT). The UPSIT provided the needed scientific basis for many subsequent studies

Hawkes Ch. Olfaction in neurodegenerative disorder. Mov Disord. 2003;18:364-372. This excellent review summarizes our knowledge about olfaction in various neurodegenerative conditions, and focuses on the intriguing role of smell disturbance in Parkinson disease and Alzheimer dementia

Rubin G, Ben David U, Gornish M, et al. Meningiomas of the anterior cranial fossa floor: review of 67 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;129:26-30. In this retrospective review, the authors describe the clinical characteristic and prognosis of their large cohort of patients with anterior fossa meningiomas