95 Cranial Nerve Disorders

• The 12 cranial nerves supply motor and sensory innervation to the head and neck.

• Cranial nerve disorders generally cause visual disturbances, facial weakness, or facial pain or paresthesias, depending on the nerve or nerves involved.

• Trigeminal neuralgia and Bell palsy are common cranial nerve disorders.

• A thorough history and physical examination should focus on assessing the potential for trauma (skull fracture), tumor, cerebrovascular accidents, vascular derangements (aneurysm, dissection, thrombosis), and infection (meningitis, abscess).

• The presence of concomitant focal neurologic or systemic signs should heighten suspicion for a central rather than a peripheral cause of the neurologic dysfunction.

Epidemiology

Cranial neuropathies are a heterogeneous group of disorders with a variety of causes. Trauma is a common cause, and diabetes and hypertension are common comorbid conditions. Cranial nerves I, VI, and VII are the most frequently affected after minor head trauma.1 Trigeminal neuralgia is a common cause of facial pain that affects approximately 4.5 per 100,000 individuals; women are affected twice as often as men, and it is more common in those older than 60 years.2 Trigeminal neuralgia can be severely debilitating and has been termed the “suicide disease.”3 Bell palsy is the most common cause of acute facial paralysis worldwide. The peak age at incidence has been reported to be between 15 and 45 years,4 but other investigators have noted an increased incidence in individuals older than 70.5,6 Pregnant women and patients with diabetes have an associated increased incidence of the disease. A familial association of Bell palsy is noted in 4% of cases,4 and it can cause both significant psychologic and physical morbidity.

Pathophysiology

Cranial Nerve II (Optic Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Orbital compressive tumors or aneurysms cause mass effects that compromise optic nerve function.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential patterns of visual loss are described in Box 95.1.

Box 95.1 Differential Patterns of Visual Loss

A central retinal etiology of the fovea or optic disk compromises visual acuity or causes central loss of vision in the affected eye only.

Unilateral blindness is usually associated with an optic nerve lesion, and only the affected eye has complete visual field loss.

Unilateral nasal visual field loss can be caused by an internal carotid artery aneurysm compressing the lateral optic chiasm.

Bitemporal hemianopia can be caused by a midchiasmatic lesion.

Homonymous hemianopia from an optic tract lesion causes full contralateral visual field loss in both eyes.

Homonymous quadrantanopia secondary to a Meyer loop lesion causes contralateral one-quarter visual field loss in both eyes.

Cranial Nerve III (Oculomotor Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

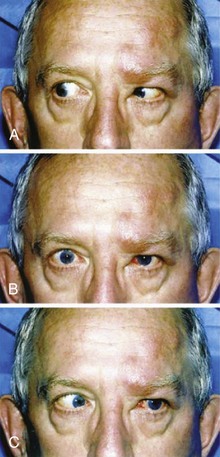

Cranial nerve III palsy is more common in patients older than 60 years and in those with diabetes or hypertension (Fig. 95.1).

Patients with herniation syndromes will have a history of trauma (Fig. 95.2), tumor, or other neurologic findings.7

Pain associated with unilateral mydriasis should alert the emergency physician (EP) to look for an aneurysm involving the terminal internal carotid artery. Computed tomographic angiography is more reliable than magnetic resonance angiography.8

Patients with an abscess or cavernous sinus thrombosis may have headaches, altered mental status, and seizures. This diagnosis should be considered in patients with signs and symptoms in the contralateral eye, previous sinus or midface infection, fever, chemosis, eyelid or periorbital edema, and exophthalmos. Extension of internal carotid artery dissection intracranially into the cavernous sinus can result in third, fourth, and sixth cranial nerve palsies.9

Cranial Nerve IV (Trochlear Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

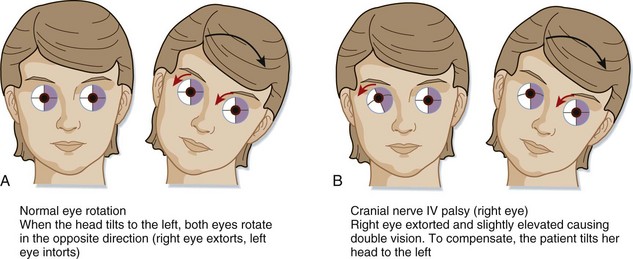

Patients with a fourth cranial nerve palsy have double vision exacerbated by looking downward. The classic complaint is difficulty going down stairs. Most commonly, a history of trauma is reported. On physical examination the patient may unconsciously tilt the head away from the affected side (Fig. 95.3). Etiologic mechanisms are similar to those for the third cranial nerve and include inflammatory processes, trauma, and vascular causes.10

Cranial Nerve V (Trigeminal Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

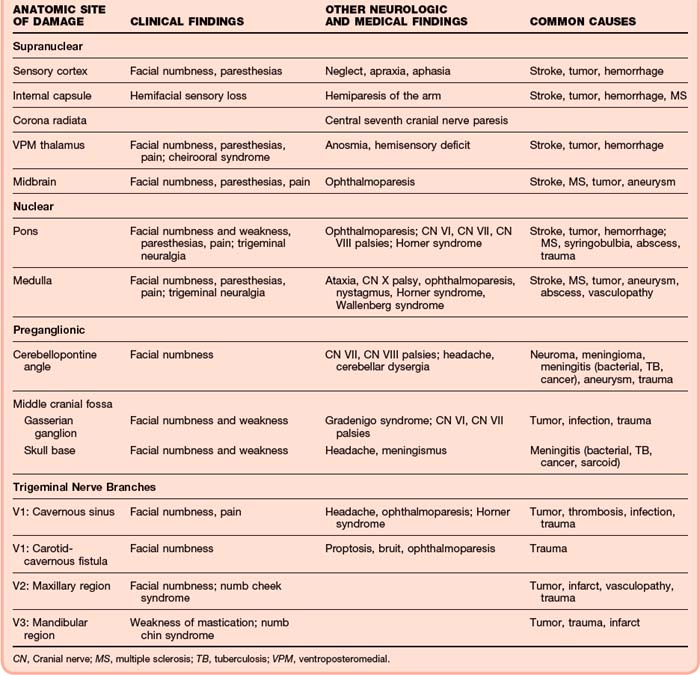

The presence of associated cranial nerve deficits (III, IV, IV, or any combination of these nerves) suggests cavernous sinus involvement. In the setting of trauma, if a bruit over the orbit can be detected, a carotid–cavernous sinus fistula may be present. Associated involvement of cranial nerve VII or VIII or gait ataxia should raise suspicion for a cerebellopontine angle or lateral pontine tumor (Table 95.1).

Associated Horner syndrome may indicate a cervical or lateral brainstem lesion.

The main categories of trigeminal nerve dysfunction are trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuropathy. A sudden onset of symptoms should raise suspicion for a vascular, traumatic, or demyelinating cause, whereas a more indolent course suggests tumor or inflammation (Table 95.2).

Table 95.2 Selected Specific Causes Associated with Trigeminal Nerve Disorders

| ETIOLOGIC CATEGORY | SELECTED SPECIFIC CAUSES |

|---|---|

| Structural Disorders | |

| Developmental | Brainstem vascular loop, syringobulbia |

| Degenerative and compressive | Paget disease |

| Hereditary and Degenerative Disorders | |

| Chromosomal abnormalities, neurocutaneous disorders | Hereditary sensorimotor neuropathy type I, neurofibromatosis (schwannoma) |

| Degenerative motor, sensory, and autonomic disorders | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| Acquired Metabolic and Nutritional Disorders | |

| Endogenous metabolic disorders | Diabetes |

| Exogenous disorders (toxins, illicit drugs) | Trichloroethylene, trichloroacetic acid |

| Nutritional deficiencies, syndromes associated with alcoholism | Thiamine, folate, vitamin B12, pyridoxine, pantothenic acid, vitamin A deficiencies |

| Infectious Disorders | |

| Viral infections | Herpes zoster, unknown |

| Nonviral infections | Bacteria, tuberculous meningitis, brain abscess, Gradenigo syndrome, leprosy, cavernous sinus thrombosis |

| HIV infection, AIDS | Opportunistic infection; abscess, herpes zosterStroke, hemorrhage, aneurysm |

| Neurovascular Disorders | |

| Neoplastic Disorders | |

| Primary neurologic tumors | Glial tumors, meningioma, schwannoma |

| Metastatic neoplasms, paraneoplastic syndromes | Lung, breast; lymphoma, carcinomatous meningitis |

| Demyelinating Disorders | |

| Central nervous system disorders | Multiple sclerosis, acute demyelinating encephalomyelitis |

| Peripheral nervous system disorders | Guillain-Barré syndrome, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathyTolosa-Hunt syndrome, sarcoidosis, lupus, orbital pseudotumor |

| Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disorders | |

| Traumatic Disorders | Carotid-cavernous fistula, cavernous sinus thrombosis, maxillary/mandibular injury |

| Epilepsy | Focal seizures |

| Headache and Facial Pain | Raeder neuralgia, cluster headache |

| Drug-Induced and Iatrogenic Neurologic Disorders | Orbital, facial, dental surgery |

AIDS, Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus.

From Goetz CG, editor. Textbook of clinical neurology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003.

Trigeminal Neuropathy

Until proved otherwise, neuropathies of cranial nerve V, the chin (numb chin; V3), and the suborbital region (numb cheek) should be presumed to be due to malignancies.11

Tic Douloureux

The term tic douloureux was coined by Nicolaus André, a French surgeon, in 1756. Its mechanism is probably compression of the trigeminal nerve root within millimeters of entry into the pons.12 The maxillary and mandibular divisions are most commonly affected, either alone or in combination. In one longitudinal case series, no cases of trigeminal neuralgia affecting both the ophthalmic and mandibular divisions were reported.2 Causes of tic douloureux are listed in Box 95.2.

Treatment

A trial of carbamazepine can be therapeutic as well as diagnostic because failure to improve with carbamazepine suggests some other cause. Treatment options are listed in Box 95.3.3 Surgical approaches are considered when medication cannot control the pain or pain medication is not tolerated.13

Box 95.3

Treatment of Trigeminal Neuralgia

Second-Line Agents

Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal)—Start at 300 mg daily and increase by 300 mg every 3 days as needed to a total daily dose of 1200 to 1800 mg divided into two doses.

Gabapentin (Neurontin)—Start at 300 mg three times daily and increase as needed to a total daily dose of 3600 mg divided into three doses. Also commonly used as first-line therapy.

Phenytoin (Dilantin)—Start at 300 mg daily and increase as needed, divided into two or three doses.

Reprinted with permission from Prasad S, Galetta S. Trigeminal neuralgia: historical notes and current concepts. Neurologist 2009;15:87–94.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with an abducens nerve palsy usually complain of double vision. The head may be turned away from the affected side to maintain binocularity. Diabetes and hypertension are common risk factors. Another common sign is “crossed eyes” (esotropia or strabismus) (Fig. 95.4).14

Differential Diagnosis

An abducens nerve palsy occurring in isolation is rare. Usually, the seventh and eighth cranial nerves are also involved, which signals a central cause. Causes of abducens nerve palsy are listed in Box 95.4.

Box 95.4 Causes of Abducens Nerve Palsy

Trauma—a blowout fracture of the orbit may result in a trapped medial rectus muscle and mimic a sixth nerve palsy

Subarachnoid disorders—hemorrhage, infection (meningitis), tumor

Vascular—intracavernous aneurysms; sixth nerve palsies are almost always the first clinical feature because of this nerve’s close relationship to the carotid artery and the fact that it is unsupported by a fibrous covering

Pseudotumor cerebri—may be manifested as an isolated abducens nerve palsy in 30% of cases

Inflammatory (postviral or demyelinating) leptomeningeal involvement secondary to carcinomatous meningitis; inflammatory or infiltrating lesions of the cavernous sinus

Cranial Nerve VII (Facial Nerve)—Bell Palsy

Mechanisms

The pathophysiology of Bell palsy has not been clearly established. Several theories have been proposed, including infectious or ischemic inflammation leading to nerve compression within the narrow canal as the nerve exits the stylomastoid foramen. Because the nerve is encased in a tight dural sheath within the temporal bone, this edema then causes additional compression of the vascular supply to the nerve.15

The cause of Bell palsy is most commonly idiopathic (66%).4 Numerous observed associations have been described in the literature. The palsy is often preceded by a viral syndrome, and a correlation has been noted with herpes simplex virus (HSV). Its association with shingles and the characteristic blistering (from varicella-zoster virus [VZV]) is given the designation Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Reactivation of VZV has also been theorized as a cause. In addition, Bell palsy may be seen in patients with Lyme disease in places where the disease is endemic.

Diabetes, hypertension, human immunodeficiency virus infection, sarcoidosis, Sjögren syndrome, parotid nerve tumors, eclampsia, amyloidosis, and the intranasal influenza vaccine have been associated with the development of Bell palsy.5,16 Other common triggers include stress, trauma, fever, tooth extraction, and a chilling episode from exposure to drafts and cold.

Complete facial weakness, severe non–ear-related pain (e.g., retroauricular, cheek), late onset of recovery or no recovery by 3 weeks, diabetes, pregnancy, age older than 60 years, hypertension, and Ramsay Hunt syndrome are risk factors for incomplete recovery.17,18

Electroneurographic studies demonstrate a steady decline in electrical activity on days 4 to 10. When excitability is retained, 90% of patients recover fully, but when excitability diminishes to absence, only 20% of patients recover completely.5

Anatomy

The geniculate ganglion contains the nerve cell bodies of the sensory taste fibers of the anterior two thirds of the tongue.19

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

To the patient, the most alarming symptom of Bell palsy is the abrupt onset of unilateral facial paralysis. Approximately 50% of patients believe that they have suffered a stroke, 25% think that they have an intracranial tumor, and the remaining 25% have no clear conception of what is wrong but are extremely anxious.4

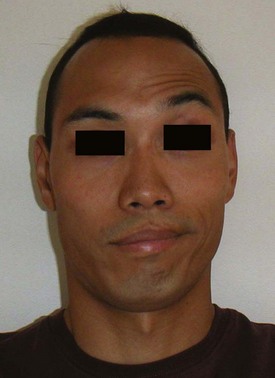

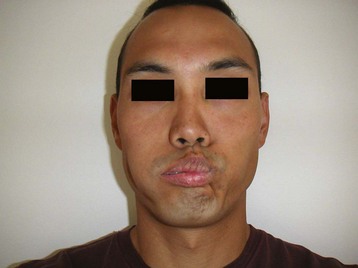

The EP may note drooping of the eyebrow or the corner of the mouth (or both) and loss of wrinkles on the forehead or the nasolabial folds (or both). Inability to raise the eyebrow and furrow the forehead is a cardinal sign of Bell palsy (Fig. 95.5). Preservation of forehead motor neuron innervation should raise suspicion for a central cause.17 Because the forehead receives bilateral upper motor neuron innervation, a central stroke will spare the forehead and allow the patient to raise the eyebrow. If the patient can do this, it is not Bell palsy.

Loss of nasolabial fold and nasal flaring is common. Loss of buccinator strength causes an inability to blow out the cheeks. An inability to close the eye on the affected side is a hallmark of Bell palsy. Speech is affected and may sound slurred or garbled, similar to dysarthria from a stroke. An asymmetric smile is often noted on examination (Fig. 95.6).

The signs and symptoms vary depending on the site of the affected nerve. They are listed in Box 95.5.

Box 95.5 Signs and Symptoms of Bell Palsy

Overt paralysis preceded by a sensation of subjective numbness or weakness on the affected side

Ear pain in the external auditory canal

Fullness or snapping sound in the affected ear

Inability to keep liquids in the mouth or chew

Noticeable dryness of the oral and nasal mucous membranes on the affected side

Diagnostic Testing and Differential Diagnosis

The “blow out your cheeks” test (Fig. 95.7) demonstrates loss of buccinator function. A sensitive variation of this test is to ask patients to hold water in their mouth and contract the buccal muscles. The water will either dribble out of the corner of the mouth or shoot across the room.

The presence of vesicles on the tympanic membrane or in the oropharynx (Fig. 95.8) or the presence of grouped vesicular lesions on the face or around the ear (Fig. 95.9) suggests a diagnosis of Ramsay Hunt syndrome.

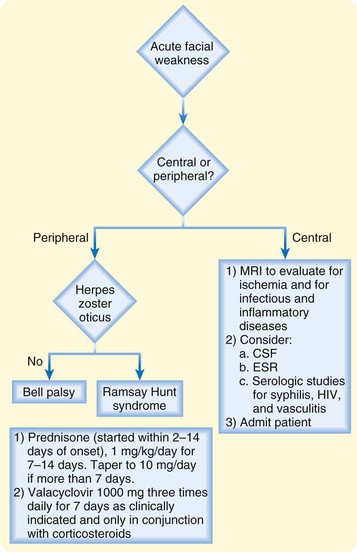

Treatment

The algorithm shown in Figure 95.10 outlines the treatment of patients with Bell palsy.

The evidence available indicates that steroids are safe and effective in shortening the course of the neurologic deficit and improving facial function.5,20–24 Patients receiving steroid therapy are up to 1.2 times more likely to attain good functional outcomes than untreated patients are.25 Corticosteroids reduce the risk for unsatisfactory recovery by 9%, with the number needed to benefit (NNTB) being 11.21 Corticosteroids were also associated with a 14% absolute reduction in risk for synkinesis and autonomic dysfunction, with an NNTB of 7.22

No studies have demonstrated significantly worse facial functional outcomes in patients treated with steroids.21,22,25

The most commonly reported treatment regimen is oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg up to 70 mg/day for a 10-day course. Dosing can be once daily or split into twice daily. The starting dose is continued for 6 days and tapered over the next 4 days.22,25 Alternatively, prednisone, 1 mg/kg/day, may be given for 7 days without a taper.4

Recent studies and metaanalyses have questioned the benefit of using antivirals for the treatment of Bell palsy.20–2426 Antiviral agents used alone did not provide any benefit over placebo, and their use as the sole therapeutic agent is not recommended.20 When combined with corticosteroid therapy, antiviral therapy may have incremental benefit,21 but this remains to be shown conclusively. Therefore, until definitive studies are performed, clinical judgment will probably guide the use of antiviral therapy in cases in which a viral cause is strongly suspected (i.e., patients in whom HSV or VZV is contributory). Valacyclovir, 1 g three times daily for 7 days, can be prescribed in conjunction with corticosteroids.

Prognosis

In a prospective study describing the spontaneous untreated course of idiopathic peripheral nerve palsy in patients with diabetes, 38% of patients had complete palsies, and only 25% regained normal facial muscle function.4 This is significantly worse than the observed rate of spontaneous full recovery in nondiabetic patients.27 Recurrence is rare (6.3%28) and should prompt a work-up for other causes such as myasthenia gravis, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, Lyme disease, and rarely, Guillain-Barré syndrome.5,29,30

Cranial Nerve VIII (Vestibulocochlear Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with vestibulocochlear nerve dysfunction usually exhibit various degrees of hearing loss, tinnitus, vertigo, falling, and imbalance. The mechanism is asymmetric integration of vestibular input to the central nervous system or asymmetric disruption of sensory input from the vestibular organs.31 If the vertigo is severe, nausea and vomiting also occur. Symptoms may be constant or episodic. Vestibular neuronitis causes vertigo that lasts for weeks, and central vertigo may persist for years.32

The examination should be focused on determining reproducibility of the symptoms, gait, balance, and ataxia; on evaluation of possible acute stroke symptoms; and on the character of the nystagmus and severity of the ataxia. The presence or absence of associated cerebellar signs such as lateralizing dysmetria, motor weakness, sensory loss, and abnormal reflexes should be noted, as well as the Babinski reflex and cranial nerve abnormalities such as ophthalmoplegia, dysarthria, and Horner syndrome.31 Abnormalities in cerebellar function should prompt consideration of a central cause. Patients should also be examined for vertical and rotatory nystagmus, which are not typically present in patients with peripheral vertigo; their presence warrants imaging and neurologic evaluation.

Diagnostic Testing and Differential Diagnosis

The Dix-Hallpike maneuver is commonly used to elicit positional nystagmus (see Fig. 96.1), which is associated with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo and usually lasts 5 to 60 seconds. Prolonged nystagmus is unlikely to be a result of this disorder. Gait and balance can be assessed with tandem walking and the Romberg test. Ataxia and lateralizing dysmetria can be assessed with finger-to-nose and heel-knee-shin testing. Hearing can be evaluated with the finger rub or finger snap, the Weber test, and the Rinne test. The ear and external auditory canal should be examined for evidence of cerumen, otitis media, perforation of the tympanic membrane, and mass lesions.

Cranial Nerve IX (Glossopharyngeal Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with glossopharyngeal nerve palsy usually have associated symptoms involving other cranial nerves, most commonly cranial nerves X and XI. The most common symptoms are dysphagia and choking. If the vagus nerve is involved, the patient complains of hoarseness and demonstrates ipsilateral paralysis of the soft palate. Head, neck, and oral trauma or surgery can cause acute dysfunction of cranial nerve IX. Glossopharyngeal nerve palsy is a known complication of tonsillectomy surgery.33

Cranial Nerve XI (Accessory Nerve)

Anatomy

The accessory nerve provides motor function to the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.

Cranial Nerve XII (Hypoglossal Nerve)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Patients with hypoglossal nerve palsies usually have unilateral tongue weakness.

Differential Diagnosis

The primary diagnostic consideration is distinguishing an upper from a lower motor neuron lesion. An upper motor neuron lesion causes contralateral tongue deviation and fasciculations, and tongue atrophy is absent. A lower motor neuron lesion causes ipsilateral tongue deviation and fasciculations, and tongue atrophy is present. A 26-year review of 100 cases of hypoglossal nerve palsy revealed that tumors, predominantly malignant ones, produced nearly half of the palsies. Only 15% of patients made a complete or nearly complete recovery.34 External lesions that cause compression or stretching of the nerve include internal carotid artery dissection or aneurysm, intracranial tumor, abscess, and other pharyngeal space tumors.

Treatment

Tips and Tricks

Patients with palsies of any of the 12 cranial nerves have heterogeneous symptoms reflecting the intrinsic function of each nerve.

Patients with cranial nerve disorders generally have visual disturbances, facial weakness or pain, or paresthesias, depending on the nerve or nerves involved.

Knowledge of the function of each of the cranial nerves helps the emergency physician recognize the classic signs and symptoms of cranial nerve palsies.

Trigeminal neuralgia and Bell palsy are common cranial nerve disorders encountered in the emergency department.

Corticosteroids are beneficial in the treatment of Bell palsy. Additional benefit of antiviral therapy is unclear.

The majority of patients with an acute onset of facial weakness are concerned about a stroke.

A thorough history and physical examination should be focused on assessing the potential for trauma (skull fracture), tumor, cerebrovascular accident, vascular derangements (aneurysm, dissection, thrombosis), and infection (meningitis, abscess). Morbidity primary results from these entities.

The diagnostic work-up and disposition depend on the clinical findings.

The presence of concomitant focal neurologic or systemic signs should heighten suspicion for a central rather than a peripheral cause of the neurologic dysfunction.

de Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:985–993.

Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell’s palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:993–1000.

Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1323–1331.

Gilden D. Treatment of Bell’s palsy—the pendulum has swung back to steroids alone. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:976–977.

Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, et al. Corticosteroids for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2010. CD001942

Sherbino J. Evidence-based emergency medicine: clinical synopsis. Do antiviral medications improve recovery in patients with Bell’s palsy? Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:475–476.

Worster A, Keim SM, Sahsi R, et al. Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine (BEEM) Group. Do either corticosteroids or antiviral agents reduce the risk of long-term facial paresis in patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy? J Emerg Med. 2010;38:518–523.

1 Coello AF, Canals AG, Gonzalez JM, et al. Cranial nerve injury after minor head trauma. J Neurosurg. 2010;113:547–555.

2 Katusic S, Beard CM, Bergstralh E, et al. Incidence and clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia, Rochester, Minnesota, 1945-1984. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:89–95.

3 Prasad S, Galetta S. Trigeminal neuralgia: historical notes and current concepts. Neurologist. 2009;15:87–94.

4 Peitersen E. Bell’s palsy: the spontaneous course of 2500 peripheral facial nerve palsies of different etiologies. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 2002;549:4–30.

5 Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1323–1331.

6 Katusic SK, Beard CM, Wiederholt WC, et al. Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell’s palsy, Rochester, Minnesota, 1968-1982. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:622–627.

7 Baker C, Cannon J. Images in clinical medicine. Traumatic cranial nerve palsy. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1955.

8 Chaudhary N, Davagnanam I, Ansari SA, et al. Imaging of intracranial aneurysms causing isolated third cranial nerve palsy. J Neuroophthalmol. 2009;29:238–244.

9 Menon RK, Norris JW. Cervical arterial dissection: current concepts. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1142:200–217.

10 Brazis PW. Isolated palsies of cranial nerves III, IV, and VI. Semin Neurol. 2009;29:14–28.

11 Vahedi K, Bousser MG. Clinical examination of paralysis of the cranial nerves and principal etiologies. In: Doyon D, Marsot-Dupuch K, Francke JP. The cranial nerves. Teterboro, NJ: Icon Learning Systems; 2004:1–6.

12 Love S, Coakham HB. Trigeminal neuralgia: pathology and pathogenesis. Brain. 2001;124:2347–2360.

13 Toda K. Operative treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: review of current techniques. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008;106:788–805.

14 Jude E, Chakraborty A. Images in clinical medicine. Left sixth cranial nerve palsy with herpes zoster ophthalmicus. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:e14.

15 Gacek RR. Hilger: The nature of Bell’s palsy (Laryngoscope 1949;59:228-35). Laryngoscope. 1996;106:1465–1468.

16 Mutsch M, Zhou W, Rhodes P, et al. Use of the inactivated intranasal influenza vaccine and the risk of Bell’s palsy in Switzerland. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:896–903.

17 Allen D, Dunn L. Aciclovir or valaciclovir for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;3:CD001869.

18 Holland NJ, Weiner GM. Recent developments in Bell’s palsy. BMJ. 2004;329:553–557.

19 Wilson-Pauwels L, Akesson EJ. Cranial nerves—anatomy and clinical comments. Toronto: BC Decker; 1988:177.

20 Engström M, Berg T, Stjernquist-Desatnik A, et al. Prednisolone and valaciclovir in Bell’s palsy: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:993–1000.

21 de Almeida JR, Al Khabori M, Guyatt GH, et al. Combined corticosteroid and antiviral treatment for Bell palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;302:985–993.

22 Salinas RA, Alvarez G, Daly F, et al. Corticosteroids for Bell’s palsy (idiopathic facial paralysis). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;3:CD001942.

23 Worster A, Keim SM, Sahsi R, et al. Best Evidence in Emergency Medicine (BEEM) Group. Do either corticosteroids or antiviral agents reduce the risk of long-term facial paresis in patients with new-onset Bell’s palsy? J Emerg Med. 2010;38:518–523.

24 Sherbino J. Evidence-based emergency medicine: clinical synopsis. Do antiviral medications improve recovery in patients with Bell’s palsy? Ann Emerg Med. 2010;55:475–476.

25 Grogan PM, Gronseth GS. Practice parameter: steroids, acyclovir, and surgery for Bell’s palsy (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:830–836.

26 Gilden D. Treatment of Bell’s palsy—the pendulum has swung back to steroids alone. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:976–977.

27 Kanazawa A, Haginomori S, Takamaki A, et al. Prognosis for Bell’s palsy: a comparison of diabetic and nondiabetic patients. Acta Otolaryngol. 2007;127:888–891.

28 Katusic SK, Beard CM, Wiederholt WC, et al. Incidence, clinical features, and prognosis in Bell’s palsy, Rochester, Minnesota, 1968-1982. Ann Neurol. 1986;20:622–627.

29 Keane JR. Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology. 1994;44:1198–1202.

30 English JB, Stommel EW, Bernat JL. Recurrent Bell’s palsy. Neurology. 1996;47:604–605.

31 Delaney KA. Bedside diagnosis of vertigo: value of the history and neurological examination. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10:1388–1395.

32 Hain TC. Cranial nerve VIII: vestibulocochlear system. In: Goetz CG, ed. Textbook of clinical neurology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003:195–210.

33 Windfuhr JP, Schlöndorff G, Sesterhenn AM, et al. From the expert’s office: localized neural lesions following tonsillectomy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:1621–1640.

34 Keane JR. Twelfth-nerve palsy. Analysis of 100 cases. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:561–566.