5

Cornea

Trauma

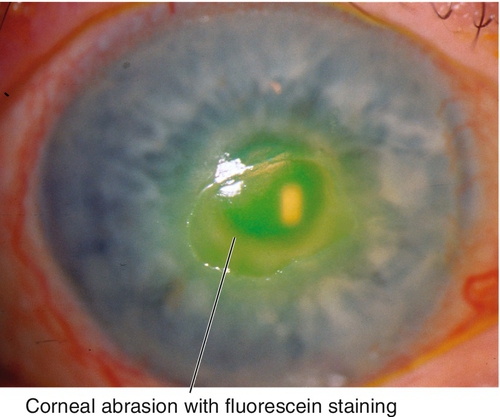

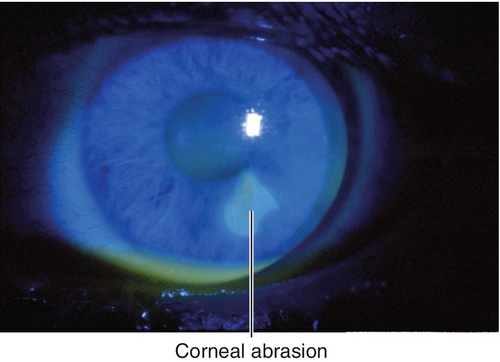

Abrasion

Corneal epithelial defect usually due to trauma. Patients note pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and red eye. May have normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, and an epithelial defect that stains with fluorescein.

• Consider topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (ketorolac tromethamine [Acular], nepafenac [Nevanac, Ilevro], bromfenac [Bromday, Prolensa], or diclofenac sodium [Voltaren] tid for 48–72 hours) for pain.

• Consider topical cycloplegic (cyclopentolate 1% bid) for pain and photophobia.

• Pressure patch or bandage contact lens if area larger than 10 mm2. (Note: DO NOT patch if patient is contact lens wearer, there is corneal infiltrate, or injury caused by plant material, as these scenarios represent high risk for infectious keratitis if patched; no patching necessary if area of abrasion is < 10 mm2.)

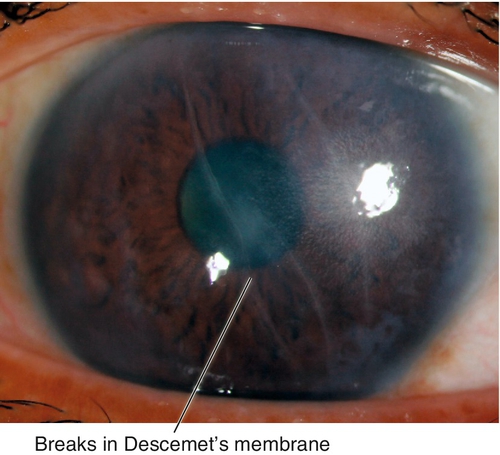

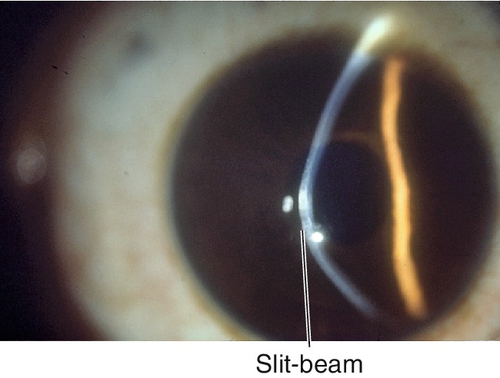

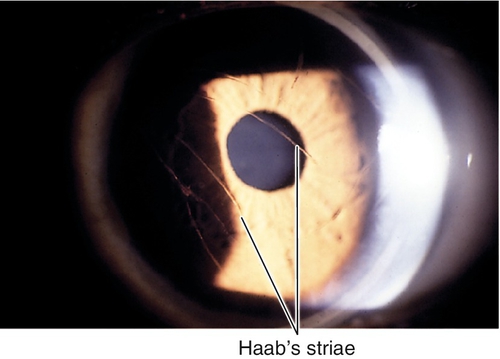

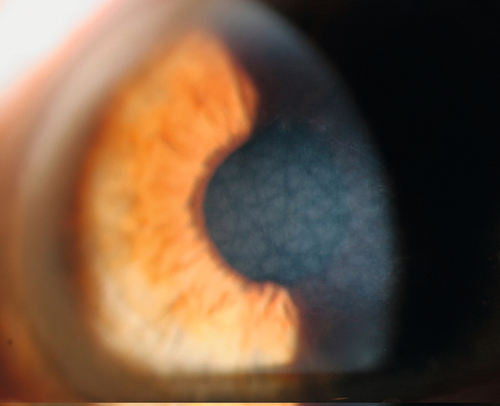

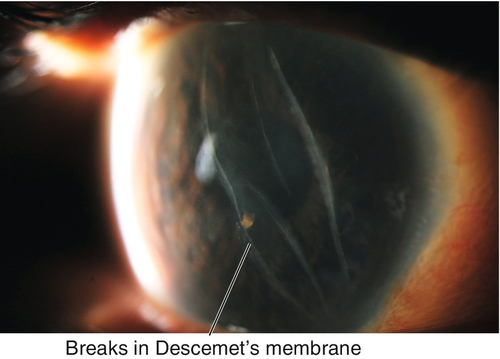

Birth Trauma

Vertical or oblique breaks in Descemet’s membrane due to forceps injury at birth. Results in acute corneal edema, scars in Descemet’s membrane; associated with astigmatism and amblyopia; may develop corneal decompensation and bullous keratopathy later in life.

• Consider Descemet’s stripping automated endothelial keratoplasty (DSAEK), Descemet’s membrane endothelial keratoplasty (DMEK), or penetrating keratoplasty for corneal decompensation.

Figure 5-4 Same patient as Figure 5-3 demonstrating the corneal scars as seen with sclerotic scatter of the slit-beam light.

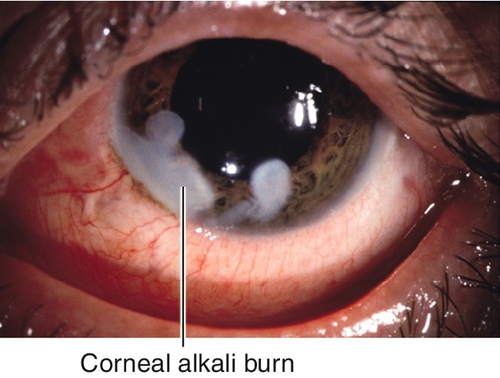

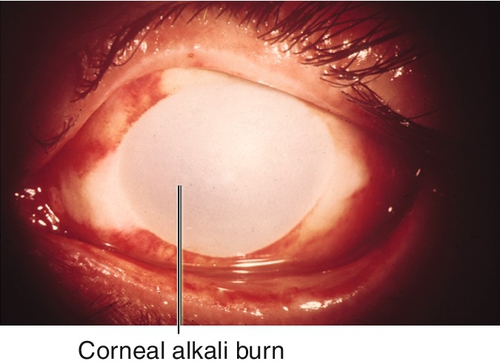

Burn

Corneal tissue destruction (epithelium and stroma) due to chemical (acid or base) or thermal (e.g., welding, intense sunlight, tanning lamp) injury; alkali causes most severe injury (penetrates and disrupts lipid membranes) and may cause perforation. Patients note pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and red eye. May have normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, epithelial defects that stain with fluorescein, and scleral or limbal blanching due to ischemia in severe chemical burns. Prognosis variable, worst for severe alkali burns.

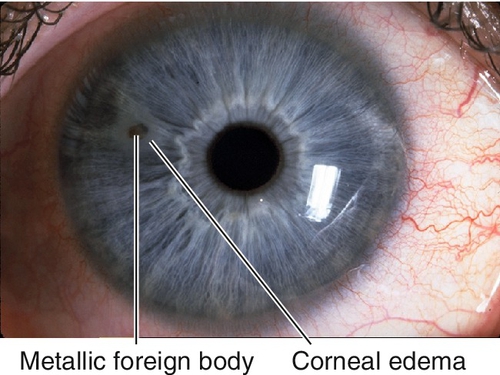

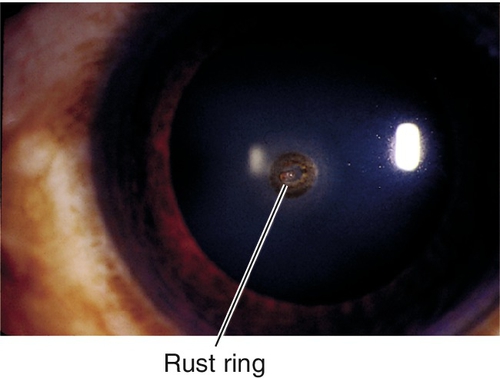

Foreign Body

Foreign material on or in cornea; usually metal, glass, or organic material; may have associated rust ring if metallic. Patients note pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and red eye; may be asymptomatic if deep and chronic. May have normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, foreign body, rust ring, epithelial defect that stains with fluorescein, corneal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare. Usually good prognosis unless rust ring or scarring involves visual axis.

• Remove rust ring with Alger brush or automated burr.

• Seidel test if deep foreign body to rule out open globe (see below).

• Topical antibiotic (polymyxin B sulfate-trimethoprim [Polytrim], moxifloxacin [Vigamox]/gatifloxacin [Zymaxid], or tobramycin [Tobrex] tid–qid).

• Consider topical cycloplegic (cyclopentolate 1% bid) for pain.

• Pressure patch or bandage contact lens as needed (same indications as for corneal abrasion; see above).

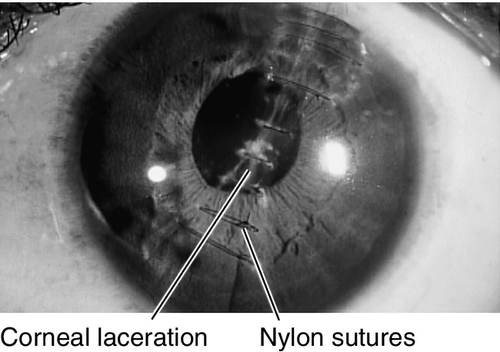

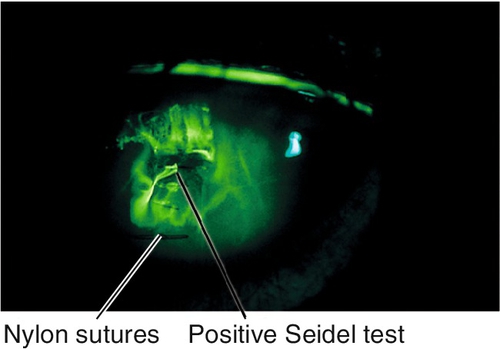

Laceration

Partial- or full-thickness cut in cornea (see Open Globe section in Chapter 4) due to trauma. Patients note pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, and red eye. May have normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, intraocular foreign body, positive Seidel test, corneal edema, breaks or scars in Descemet’s membrane, anterior chamber cells and flare, low intraocular pressure. Potentially good prognosis unless laceration crosses the visual axis.

• Partial-thickness lacerations require topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (gatifloxacin [Zymaxid] or moxifloxacin [Vigamox] tid–qid) and cycloplegic (cyclopentolate 1% or scopolamine 0.25% tid).

• Daily follow-up until wound has healed.

• Pressure patch or bandage contact lens as needed for self-sealing or small wounds; if wound gape exists, consider surgical repair.

• Full-thickness lacerations usually require surgical repair (see Open Globe section in Chapter 4).

• Consider orbital radiographs or computed tomography (CT) scan to rule out intraocular foreign body when full-thickness laceration exists; magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is contraindicated if foreign body is metallic.

Recurrent Erosion

Recurrent bouts of pain, foreign body sensation, photophobia, tearing, red eye, and spontaneous corneal epithelial defect usually upon awakening. Associated with anterior basement membrane dystrophy in 50% of cases, or previous traumatic corneal abrasion (usually from superficial shearing injury such as from a fingernail, paper, plant, or brush); also occurs in Meesman’s, Reis–Bücklers, lattice, granular, Fuchs’, and posterior polymorphous dystrophies, and rarely after surgery (cataract or corneal refractive).

• Topical lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears up to q1h or Muro 128 drops.

• Consider debridement (manual or with 20% alcohol for 30–40 seconds), diamond burr polishing, bandage contact lens, anterior stromal puncture /reinforcement, Nd : YAG laser reinforcement, superficial keratectomy, or phototherapeutic keratectomy (PTK) for multiple recurrences.

• Consider doxycycline 50 mg po bid for 2 months (matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibitor) and topical steroid tid for 2–3 weeks.

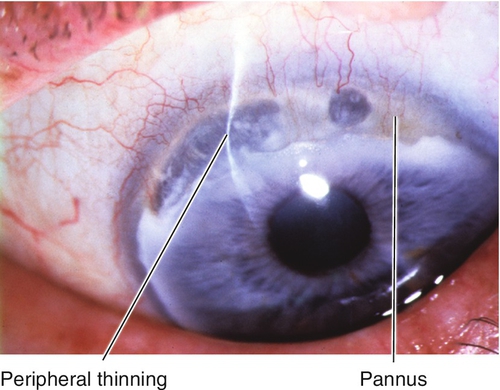

Peripheral Ulcerative Keratitis

Definition

Progressive stromal ulceration and thinning of the peripheral cornea with an overlying epithelial defect associated with inflammation.

Etiology

Due to noninfectious systemic or local diseases as well as systemic or local infections.

Marginal Keratolysis

Acute peripheral ulcerative keratitis (PUK) due to an autoimmune or collagen vascular disease (rheumatoid arthritis [most common], systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, relapsing polychondritis, and Wegener’s granulomatosis).

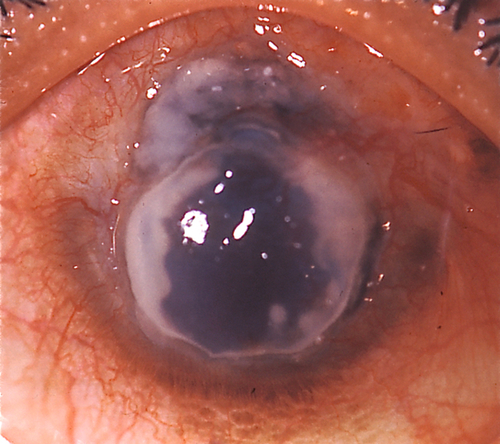

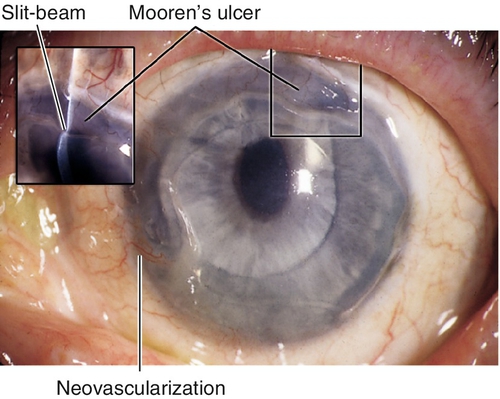

Mooren’s Ulcer

Idiopathic. Two types:

Type I

More common (75%), benign, and unilateral; occurs in older patients; responds to conservative management.

Type II

Progressive and bilateral; occurs in younger patients; more common in African-American males; may be associated with coexistent parasitemia.

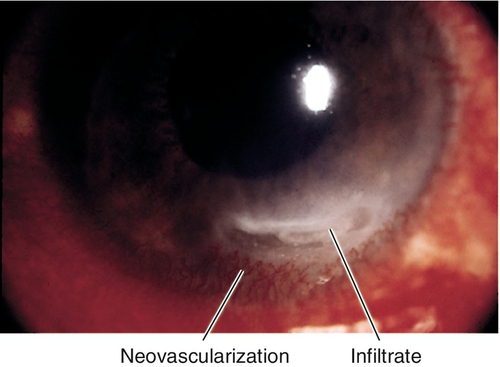

Staphylococcal Marginal Keratitis

Immune response (hypersensitivity) to Staphylococcus aureus; associated with staphylococcal blepharitis, rosacea, phlyctenule, and vascularization.

Symptoms

Pain, tearing, photophobia, red eye, and decreased vision; may be asymptomatic.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, corneal thinning, corneal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare, hypopyon; may have corneal infiltrate; may perforate.

Marginal Keratolysis

Acute ulceration with rapid progression, usually in one sector; corneal epithelium absent; melting resolves after healing of overlying epithelium; may have associated scleritis.

Mooren’s Ulcer

Thinning and ulceration that spreads circumferentially and then centrally with undermining of the leading edge; may develop neovascularization.

Staphylococcal Marginal Keratitis

Ulceration and white infiltrate(s) 1–2 mm from the limbus with an intervening clear zone; often stains with fluorescein; may progress to a ring ulcer or become superinfected.

Differential Diagnosis

Infectious ulcer, sterile ulcer (diagnosis of exclusion), Terrien’s marginal degeneration, pellucid marginal degeneration, senile furrow degeneration.

Evaluation

• Consider corneal topography (computerized videokeratography).

• Lab tests: Complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, urinalysis (UA); consider hepatitis C antigen (Mooren’s ulcer).

• Consider cultures or smears to rule out infectious etiology.

• Medical or rheumatology consultation for systemic disorders or when treatment with immunosuppressive medications is anticipated.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; poor for marginal keratolysis and Mooren’s ulcer.

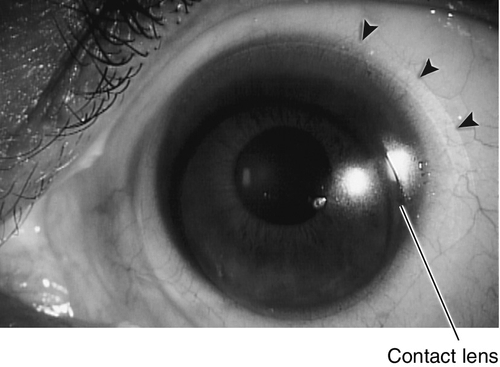

Contact-Lens-Related Problems

Definition

A variety of abnormalities induced by contact lenses. Several types of lenses exist, broadly divided into rigid and soft lenses. They are used primarily to correct refractive errors (myopia, hyperopia, astigmatism, and presbyopia), but also can serve as a therapeutic device (bandage lens) for unhealthy corneal surfaces or even for cosmetic use (to apparently change iris color or create a pseudopupil).

Rigid Lenses

Hard

Polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) lenses impermeable to oxygen; blinking allows tear film to enter the space beneath the lens providing nutrition to the cornea. Used for daily wear with good visual results but can lead to corneal edema and visual blur due to corneal hypoxia. Rarely used today.

Gas-permeable

Rigid lenses composed of cellulose acetate butyrate, silicone acrylate, or silicone combined with polymethylmethacrylate; high oxygen permeability allows for greater comfort and improved corneal nutrition. Used for daily wear; lens of choice for patients with keratoconus and high astigmatism. Hardest contact lens to adjust to but lowest rate of contact-lens-related keratitis. Also available as specialized and hybrid lenses (i.e., SynergEyes, Boston ocular surface prosthesis [PROSE lens]).

Soft Lenses

Daily wear

Hydrogel lenses (hydroxymethyl methacrylate); more comfortable and flexible than rigid lenses; conform to corneal surface, therefore poorly correct large degrees of astigmatism; length of time of wear depends on oxygen permeability and water content. Toric versions available up to 3 diopters.

Extended wear

Disposable lenses discarded after extended wear from 1 week to 30 days; higher risk (10–15 ×) of infectious keratitis with overnight wear (occurs in approximately 1 : 500).

Symptoms

Foreign body sensation, decreased vision, red eye, tearing, itching, burning, pain, lens awareness, and reduced contact lens wear time.

Signs and management

Corneal Abrasion

Corneal fluorescein staining due to epithelial defect; contact-lens-related etiologies include foreign bodies under lens, damaged lens, poor lens fit, corneal hypoxia, poor lens insertion or removal technique (see Trauma: Corneal Abrasion section above).

• Treat as for traumatic corneal abrasion except do not patch any size abrasion.

Corneal Hypoxia

Acute

Conjunctival injection and epithelial defect (PMMA contact lens).

• Topical antibiotic ointment (polymyxin B sulfate-bacitracin [Polysporin] tid for 3 days).

• When acute hypoxia has resolved, refit with higher Dk / L (oxygen transmissibility) contact lens.

Chronic

Punctate staining, corneal epithelial microcysts, stromal edema, and corneal neovascularization.

• Suspend contact lens use or decrease contact lens wear time.

• Refit with higher Dk / L contact lens.

Contact-Lens-Related Dendritic Keratitis

Conjunctivitis, pseudodendritic lesions.

Contact Lens Solution Hypersensitivity or Toxicity

Conjunctival injection, diffuse corneal punctate staining or erosion; occurs with solutions that contain preservatives (e.g., thimerosal).

• Identify and discontinue toxic source; thoroughly clean, rinse, and disinfect contact lenses; reinstruct patient in proper contact lens care or change system of care; replace soft contact lenses or polish rigid contact lens.

• Topical antibiotic ointment (erythromycin or bacitracin tid for 3 days); do not patch.

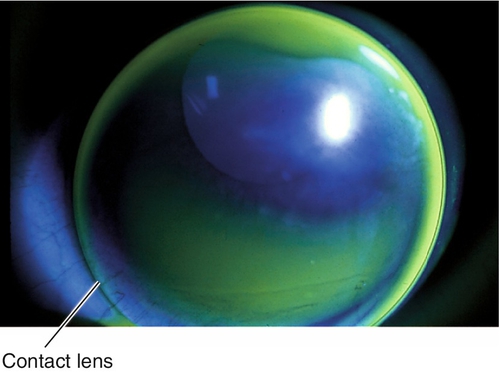

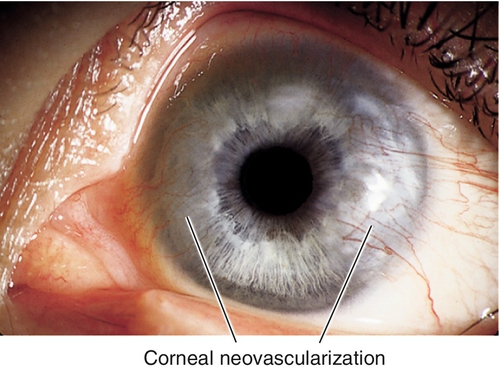

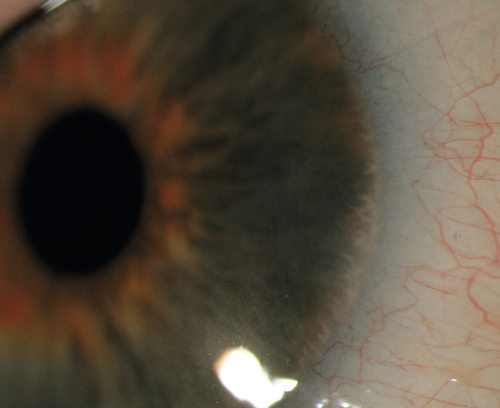

Corneal Neovascularization

Superficial or deep vascular ingrowth due to chronic hypoxia. Superior corneal pannus 1–2 mm in soft contact lens wearers is common and benign; larger than 2 mm is serious; deep vessels may cause stromal hemorrhage, lipid deposits, and scarring.

• Consider topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% qid) to cause regression.

• Consider argon laser photocoagulation of large or deep vessels to prevent stromal hemorrhage or rebleed.

• Consider bevacizumab (Avastin) subconjunctival injections adjacent to the neovascularization (2.5 mg /0.1 mL q month for up to 5 months).

Corneal Warpage

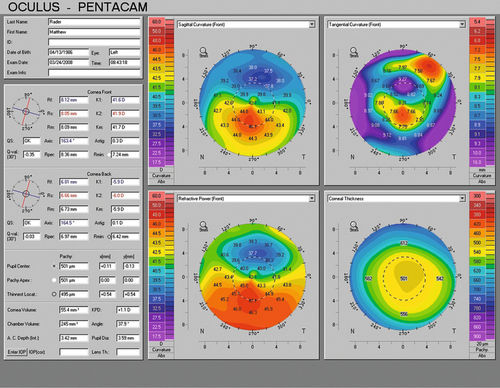

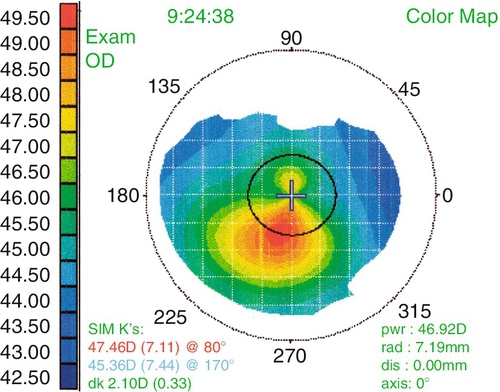

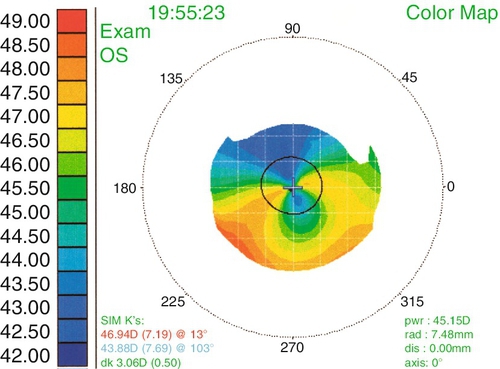

Change in corneal shape (regular and irregular astigmatism) not associated with corneal edema; related to lens material (hard > rigid gas-permeable contact lens [RGP] > soft), fit, and length of time of wear. Usually asymptomatic, but some patients may notice poorer vision with glasses or contact lens intolerance; may have loss of best spectacle-corrected visual acuity or change in refraction (especially axis of astigmatism); hallmark is abnormal corneal topography (computerized videokeratography), which shows irregular astigmatism and may mimic keratoconus (pseudokeratoconus), may affect IOL calculations.

• Periodic evaluations with refraction and corneal topography until stabilization occurs.

Damaged Contact Lens

Pain with lens insertion and prompt relief with removal; look for chips in rigid lenses and fissures or tears in soft lenses.

• Replace defective contact lens.

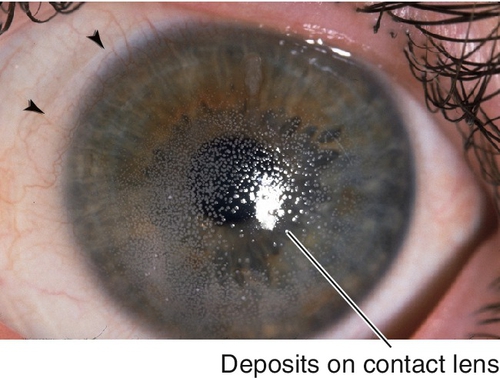

Deposits on Contact Lens

Significant contact lens deposits (film or bumps), conjunctival injection, corneal erosion, excess contact lens movement, giant papillary conjunctivitis; old contact lens.

Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis

Due to contact lens protein deposits, conjunctival contact-lens-related mechanical irritation, or soft contact lens material sensitivity reaction. Signs include large upper lid tarsal conjunctival papillae (> 0.33 mm), ropy mucous discharge, contact lens coating, and possible contact lens decentration secondary to papillae; also caused by exposed suture or ocular prosthesis (see Giant Papillary Conjunctivitis section in Chapter 4).

• Severe: Suspend contact lens use; short course (few weeks) of topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% or fluorometholone qid).

Infectious Keratitis

Pain, red eye, infiltrate with epithelial defect, and anterior chamber cells and flare. All contact lens-related corneal infiltrates should be treated as an infection, suspect Pseudomonas or Acanthamoeba. Occurs more often in extended wear and soft contact lens wearers (see Infectious Keratitis section below); fungal infections are more common in warmer climates.

• Lab tests: Cultures of cornea, contact lenses, solutions, and contact lens cases.

• Topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (fluoroquinolone [Vigamox, Zymaxid, or Besivance] or a fortified antibiotic q1h); be alert for Pseudomonas and Acanthamoeba.

• NEVER patch an infiltrate or epithelial defect in a contact lens wearer.

Sterile Corneal Infiltrates

Small (1 mm), peripheral, often multifocal, white, nummular, corneal lesions; corneal epithelium usually intact; diagnosis of exclusion.

• Use preservative-free solutions.

• Must treat as an infection (see above).

Poor Fit (Loose)

Upper eyelid irritation, limbal injection, excess contact lens movement with blinking, poor contact lens centration, lens edge bubbles, lens edge stand-off, variable keratometry mires with blinking, and lower portion of retinoscopy reflex darker and faster.

• Increase sagittal vault; choose steeper base curve or larger-diameter contact lens.

Poor Fit (Light)

Injection or indentation around limbus, minimal contact lens movement with blinking, blurred retinoscopic reflex, corneal edema, and distorted keratometry mires that clear with blinking.

• Decrease sagittal vault; choose flatter base curve or smaller-diameter contact lens.

Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis

Due to contact lens hypersensitivity reaction or poor contact lens fit. Signs include upper tarsal micropapillae, superior limbal injection, fluorescein staining of superior bulbar conjunctiva, and 12 o’clock micropannus (see Superior Limbic Keratoconjunctivitis section in Chapter 4).

• For persistent cases, consider topical steroid (prednisolone acetate 1% or fluorometholone qid) or silver nitrate 0.5–1.0% solution.

Superficial Punctate Keratitis

Punctate fluorescein staining of corneal surface due to poor lens fit, dry eye, or contact lens solution reaction (see Superficial Punctate Keratitis section below).

• Topical lubrication with artificial tears up to q1h.

• Consider topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (polymyxin B sulfate-trimethoprim [Polytrim], moxifloxacin [Vigamox], or tobramycin [Tobrex] qid) if severe.

• Refit contact lens.

• Consider punctal plugs for dry eyes.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history with attention to contact lens wear and care habits.

• Complete eye exam with attention to contact lens fit, contact lens surface, everting upper lids, conjunctiva, keratometry, and cornea.

• Consider corneal topography (computerized videokeratography).

• Consider dry eye evaluation: tear meniscus, tear break-up time, lissamine green or rose bengal staining, and Schirmer’s testing (see Chapter 4).

• Lab tests: Cultures or smears of cornea, contact lens, contact lens case, and contact lens solutions if infiltrate exists to rule out infection.

Prognosis

Usually good except for severe or central corneal infections.

Miscellaneous

Definitions

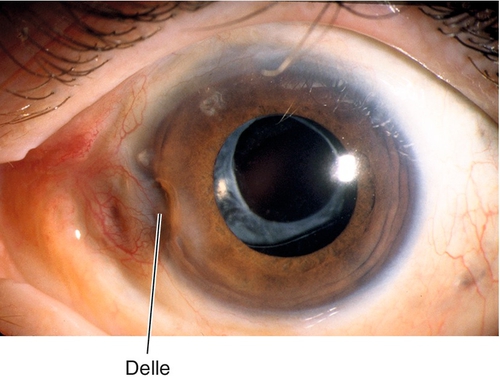

Dellen

Areas of corneal thinning secondary to corneal drying from adjacent areas of tissue elevation. Appear as focal excavations with overlying pooling of fluorescein dye; usually occur near pterygium or filtering bleb.

Exposure Keratopathy

Drying of the cornea with subsequent epithelial breakdown; due to neurotrophic (cranial nerve V palsy, cerebrovascular accident, aneurysm, multiple sclerosis, tumor, herpes simplex, herpes zoster), neuroparalytic (cranial nerve VII palsy [Bell’s palsy]), lid malposition, nocturnal lagophthalmos, or any cause of proptosis with lagophthalmos; sequelae include filamentary keratitis, corneal ulceration and scarring.

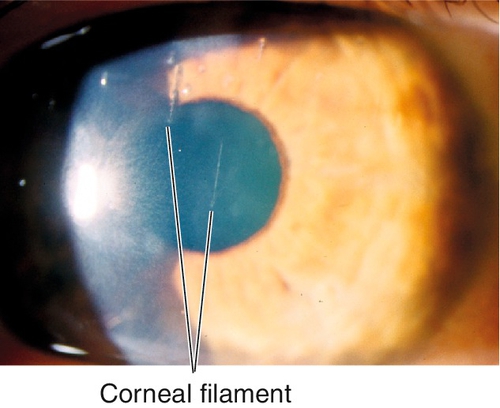

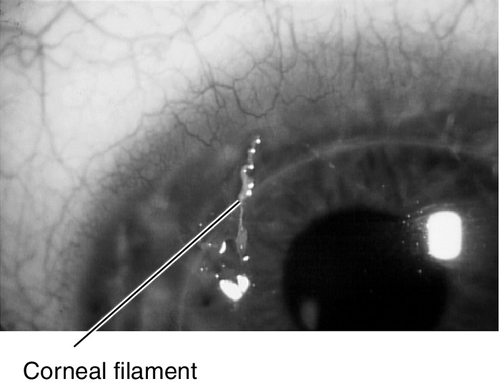

Filamentary Keratitis

Strands of mucus and desquamated epithelial cells adherent to corneal epithelium due to many conditions including any cause of dry eye, patching, recurrent erosion, bullous keratopathy, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, herpes simplex, medicamentosa, or ptosis; blinking causes pain as filaments pull on intact epithelium.

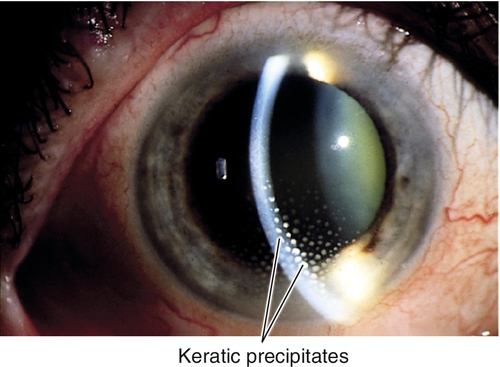

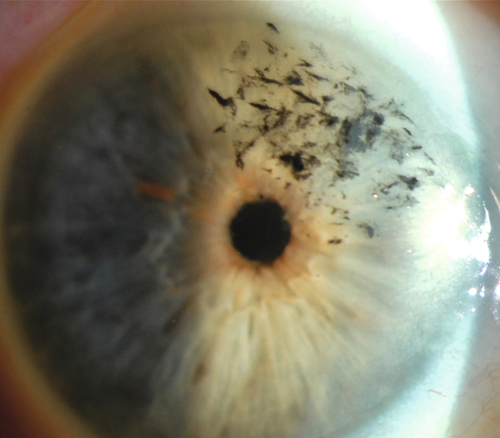

Keratic Precipitates

Fine, medium, or large deposits of inflammatory cells on the corneal endothelium due to a prior episode of inflammation. Usually round white spots, but can be translucent or pigmented; may have mutton fat (in granulomatous uveitis) or stellate (in Fuchs’ heterochromic iridocyclitis) appearance; often melt or disappear or become pigmented with time.

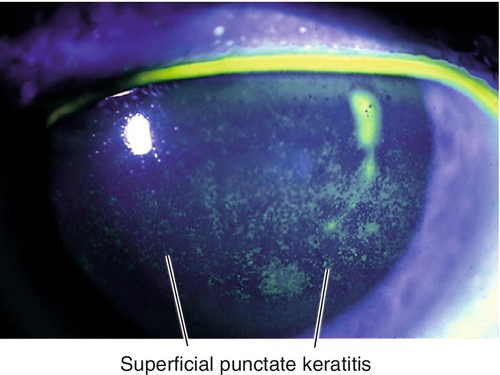

Superficial Punctate Keratitis

Nonspecific, pinpoint, epithelial defects; punctate staining with fluorescein. Associated with blepharitis, any cause of dry eye, trauma, foreign body, trichiasis, ultraviolet or chemical burn, medicamentosa, contact-lens-related, exposure, and conjunctivitis.

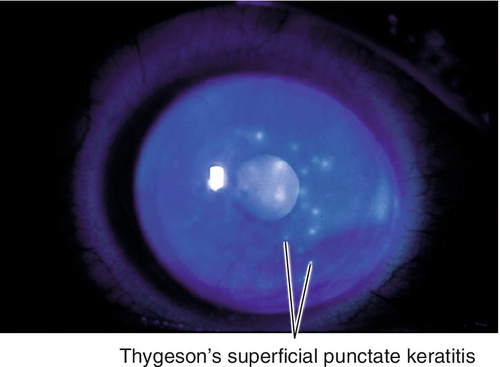

Thygeson’s Superficial Punctate Keratitis

Bilateral, recurrent, gray-white, slightly elevated epithelial lesions (similar to early subepithelial infiltrates in adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis) in a white and quiet eye; minimal or no staining with fluorescein. Unknown etiology, possibly viral; usually occurs in second to third decades.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have dryness, foreign body sensation, discharge, tearing, photophobia, red eye, and decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity; may have lagophthalmos, conjunctival injection, decreased corneal sensation, corneal staining, superficial punctate keratitis (inferiorly or in a central band in exposure keratopathy), filaments (stain with fluorescein), subepithelial infiltrates, keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells, and flare.

Differential Diagnosis

See above.

Evaluation

Prognosis

Usually good.

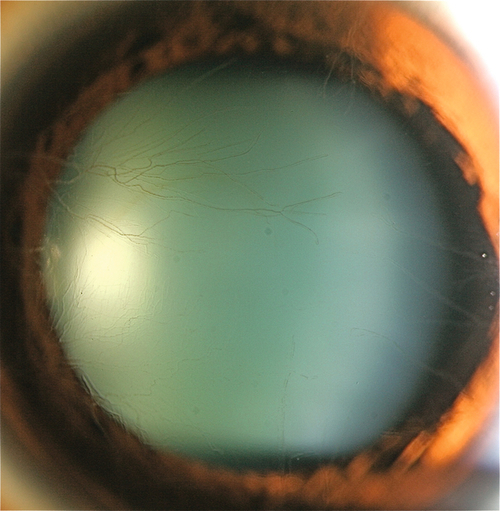

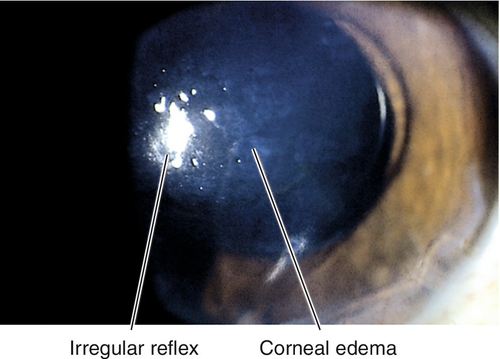

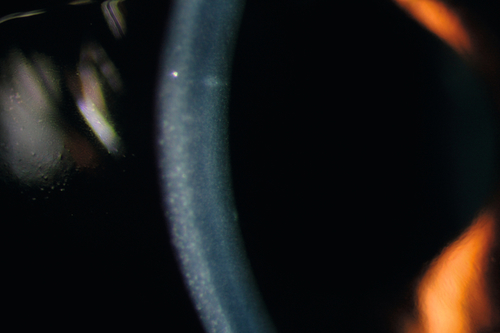

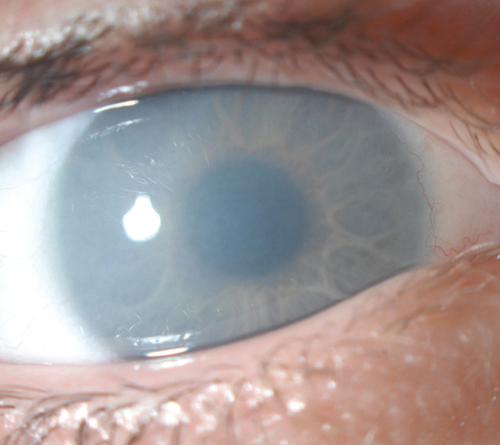

Corneal Edema

Definition

Focal or diffuse hydration and swelling of the corneal stroma (stromal edema due to endothelial dysfunction) or epithelium (intercellular or microcystic edema due to increased intraocular pressure or epithelial hypoxia).

Etiology

Inflammation, infection, Fuchs’ dystrophy, posterior polymorphous dystrophy, congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy, hydrops (keratoconus or pellucid marginal degeneration), acute angle-closure glaucoma, congenital glaucoma, previous ocular surgery (aphakic or pseudophakic bullous keratopathy or graft failure), contact lens overwear, hypotony, trauma, postoperative, iridocorneal endothelial syndrome, Brown–McLean syndrome (peripheral edema in aphakic patients possibly from endothelial contact with floppy iris), anterior segment ischemia.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have photophobia, foreign body sensation, tearing, pain, halos around lights, decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, poor corneal light reflex, thickened cornea, epithelial microcysts and bullae, nonhealing epithelial defects, superficial punctate keratitis, stromal haze, Descemet’s folds, guttata, anterior chamber cells and flare, decreased or increased intraocular pressure, iridocorneal touch, aphakia, pseudophakia, vitreous in anterior chamber; may develop subepithelial scar (pannus) late.

Differential Diagnosis

Interstitial keratitis, corneal scar, Salzmann’s nodular degeneration, crocodile shagreen, band keratopathy, anterior basement membrane dystrophy, Meesman dystrophy.

Evaluation

• Check pachymetry.

• Consider specular or confocal microscopy.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

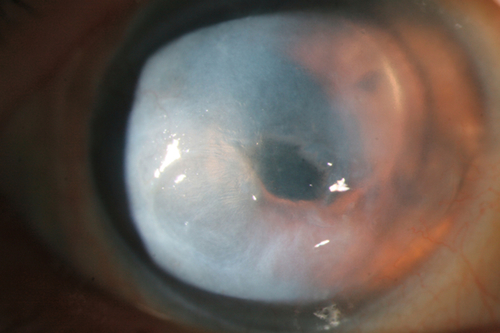

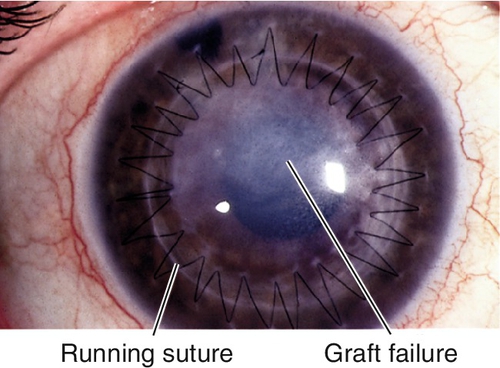

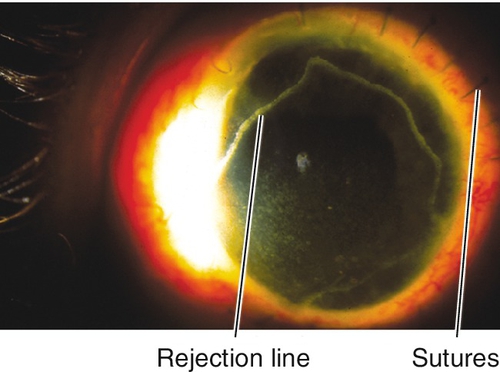

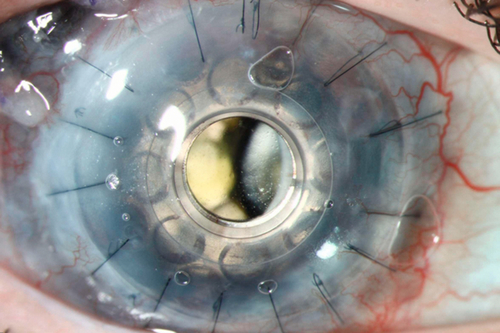

Graft Rejection or Failure

Definition

Graft Rejection

Allograft rejection is an immune response that may occur early or late after corneal transplant surgery. Epithelial rejection is rare but occurs early, stromal rejection may appear with subepithelial infiltrates, and endothelial rejection usually does not occur before 2 weeks after transplantation.

Graft Failure

Corneal edema and opacification due to primary donor failure (graft does not clear within 6 weeks after surgery), allograft rejection, recurrence of disease, glaucoma, or neovascularization.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, red eye, and decreased vision.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, corneal edema, vascularization, subepithelial infiltrates, epithelial rejection line, endothelial rejection line (Khodadoust line), keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells and flare; may have increased intraocular pressure.

Differential Diagnosis

Endophthalmitis, herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis, anterior uveitis, anterior segment ischemia.

Evaluation

• Consider pachymetry.

Prognosis

Thirty percent of patients have rejection episodes within 1 year after surgery. Often good if treated early and aggressively; poorer for a penetrating keratoplasty secondary to prior graft failure, HSV keratitis, acute corneal ulcer, chemical burn, and eyes with other ocular disease (dry eye disease, exposure keratopathy, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, uveitis, and glaucoma); better for a penetrating keratoplasty secondary to corneal edema (aphakic or pseudophakic bullous keratopathy, Fuchs’ dystrophy), keratoconus, corneal scar or opacity, and dystrophy.

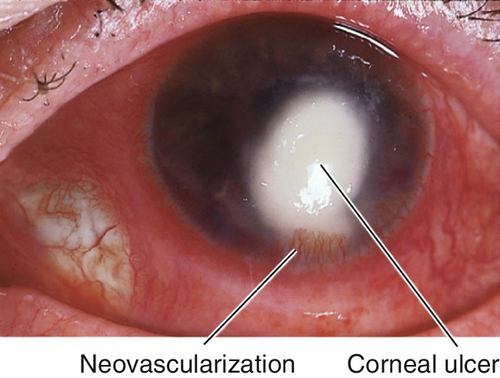

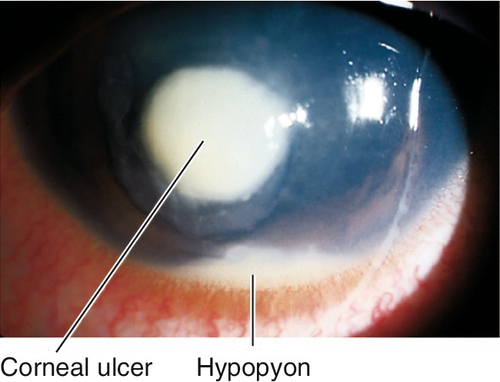

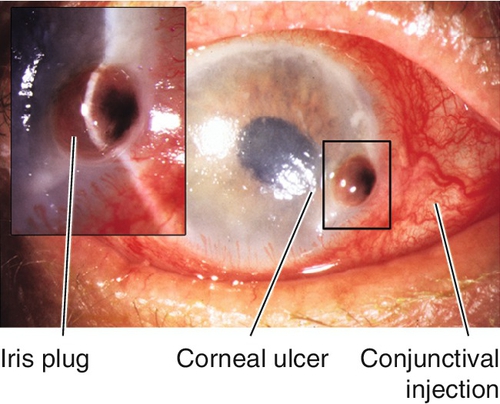

Infectious Keratitis (Corneal Ulcer)

Definition

Destruction of corneal tissue (epithelium and stroma) due to inflammation from an infectious organism. Risk factors include contact lens wear, trauma, dry eye, exposure keratopathy, bullous keratopathy, neurotrophic cornea, and lid abnormalities.

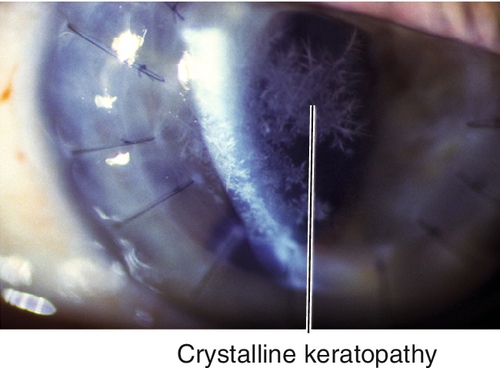

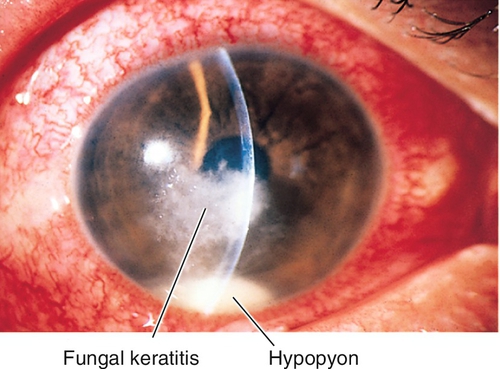

Etiology

Bacterial

Most common infectious source; usually due to Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catarrhalis; beware of Neisseria species, Corynebacterium diphtheriae, Haemophilus aegyptius, and Listeria because they can penetrate intact epithelium. Streptococcus viridans causes crystalline keratopathy (central branching cracked-glass appearance without epithelial defect; associated with chronic topical steroid use).

Fungal

Usually Aspergillus, Candida, or Fusarium species. Often have satellite infiltrates, feathery edges, endothelial plaques; can penetrate Descemet’s membrane. Associated with trauma, especially involving vegetable matter.

Parasitic

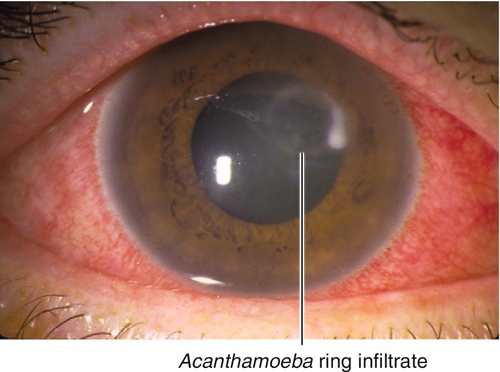

Acanthamoeba

Resembles HSV epithelial keratitis early, perineural and ring infiltrates later; usually occurs in contact lens wearers who use nonsterile water or have poor contact-lens-cleaning habits. Patients usually have pain out of proportion to signs.

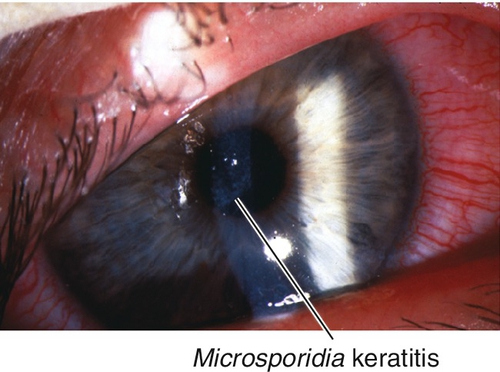

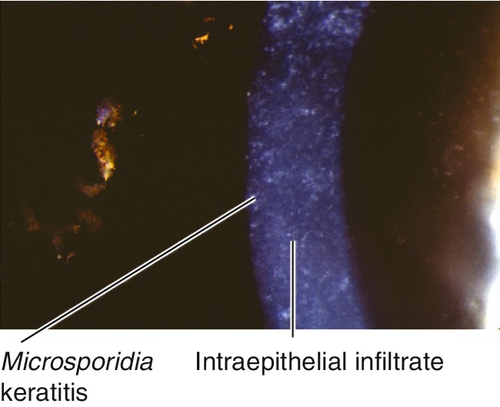

Microsporidia

Causes diffuse epithelial keratitis with small, white, intraepithelial infiltrates (organisms); occurs in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Figure 5-41 Same patient as Figure 5-40 demonstrating the intraepithelial infiltrates of Microsporidia keratitis.

Viral

Herpes simplex virus

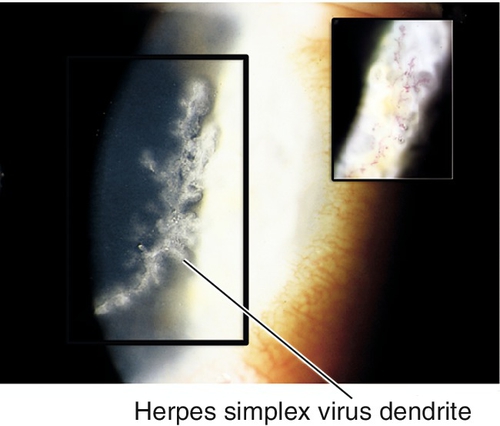

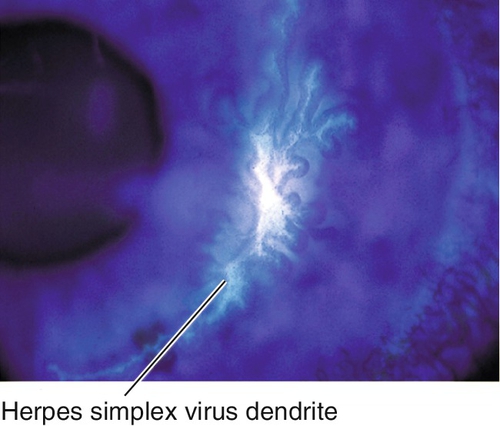

Recurrent HSV is the most common cause of central infectious keratitis and leading cause of infectious blindness in the US. Seropositivity for HSV1 is 25% at age 4 years old and 100% at age 60 years old. After primary infection, latent virus resides in trigeminal ganglion or cornea. Reactivation is associated with UV exposure, fever, stress, menses, trauma, illness, and immunosuppression. Recurrence rate is approximately 25% at 1 year and 50% at 5 years; risk of recurrence increases with number of recurrences. Various types of HSV keratitis exist:

Epithelial keratitis

Can appear as a superficial punctate keratitis, vesicles, dendrite (ulcerated, classically with terminal bulbs), geographic ulcer (scalloped borders), or marginal ulcer (dilated limbal vessels, no clear zone at limbus [vs Staph marginal ulcer that has clear zone]); associated with scarring and decreased corneal sensation (neurotrophic cornea).

Figure 5-43 Same patient as Figure 5-42 demonstrating staining of herpes simplex virus dendrite with fluorescein.

Stromal keratitis

Two types:

Necrotizing keratitis: Antigen–antibody–complement-mediated immune reaction with epithelial defect, dense stromal inflammation, ulceration, and severe iritis; risk of stromal melting and perforation.

Endothelial keratitis (endotheliitis or disciform keratitis)

Keratouveitis with corneal edema (disciform, diffuse, or linear), keratic precipitates, increased intraocular pressure, anterior chamber cells and flare.

Metaherpetic or neurotrophic (trophic) ulcer

Noninfectious, nonhealing epithelial defect with heaped-up gray edges due to HSV basement membrane disease with possible neurotrophic component.

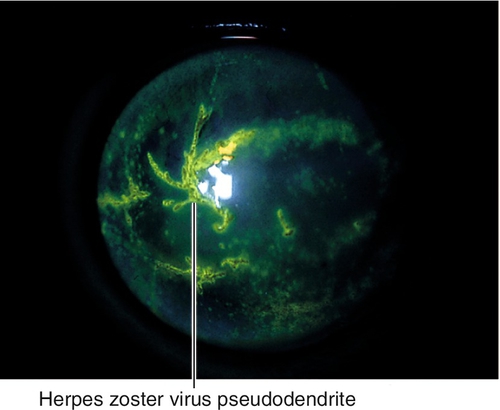

Herpes zoster virus

Ocular involvement and complications of herpes zoster ophthalmicus (HZO; see Chapter 3) are due to infection, inflammation, immune response, and scarring; may be acute, chronic, or recurrent, and can be sight-threatening. In addition to keratitis (65%), there may be lid changes, conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, uveitis, retinitis, optic neuritis, vasculitis (iris atrophy, orbital apex syndrome), and cranial nerve (III, IV, or IV) palsies; patients may also develop glaucoma and cataracts. Various types of HZV keratitis exist:

Epithelial keratitis

Can appear as a superficial punctate keratitis (early) or pseudodendrites (early or late; coarser, heaped-up epithelial plaques without terminal bulbs); virus may persist on corneal surface for 1 month.

Stromal keratitis

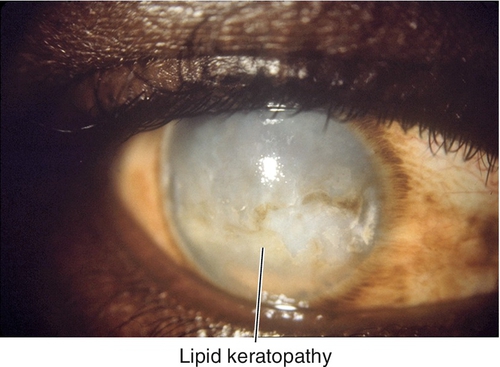

Can be anterior stromal infiltrates or disciform or peripheral edema (late) that may become chronic and cause vascularization, scarring, ulceration, and lipid keratopathy.

Endotheliitis

Viral infection or immune response that causes a keratouveitis with focal stromal edema, keratic precipitates, anterior chamber cells and flare; chronic corneal edema occurs with extensive endothelial damage.

Mucus plaque keratopathy

Mucus plaques months or years later; vary in size, shape, and location daily; associated with decreased corneal sensation, stromal keratitis, anterior segment inflammation, increased intraocular pressure, and cataracts.

Interstitial keratitis

Corneal vascularization and scarring (see Interstitial Keratitis section below).

Neurotrophic keratopathy

Decreased corneal sensation due to nerve damage; often improves spontaneously, but if not poor blink response and tear dysfunction can cause epithelial breakdown with infections, ulceration, and perforation.

Exposure keratopathy

Due to lid scarring, lagophthalmos, and neurotrophic cornea; may develop severe dry eye with ulceration and scarring (see Exposure Keratopathy section above).

Symptoms

Pain, discharge, tearing, photophobia, red eye, decreased vision; may notice white spot on cornea.

Signs

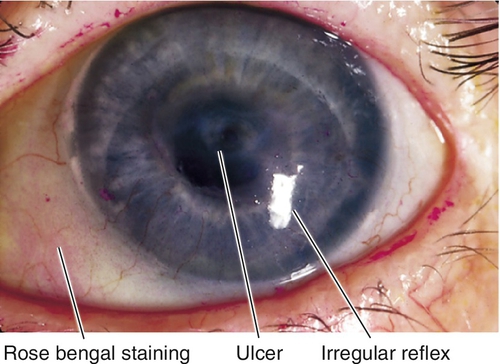

Normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, ciliary injection, white corneal infiltrate with overlying epithelial defect that stains with fluorescein, satellite lesions (fungal), corneal edema, Descemet’s folds, dendrite (HSV), pseudodendrite (HZV), cutaneous herpes vesicles, perineural and ring infiltrates (Acanthamoeba), corneal thinning, descemetocele, anterior chamber cells and flare, hypopyon, mucopurulent discharge; may have scleritis, increased intraocular pressure, iris atrophy, cataracts, retinitis, optic neuritis, or cranial nerve palsy.

Differential Diagnosis

Sterile ulcer, shield ulcer (vernal keratoconjunctivitis), staphylococcal marginal keratitis, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis subepithelial infiltrates, ocular rosacea, marginal keratolysis, Mooren’s ulcer, Terrien’s marginal degeneration, corneal abrasion, recurrent erosion, stromal scar, Thygeson’s superficial punctate keratitis, anesthetic abuse (nonhealing epithelial defect usually with ragged edges and “sick”-appearing surrounding epithelium with or without haze or an infiltrate), tyrosinemia (pseudodendrite).

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history with attention to trauma and contact lens use and care regimen.

• Complete eye exam with attention to visual acuity, lids, sclera, cornea (sensation, size and depth of ulcer, character of infiltrate, fluorescein and rose bengal staining, amount of thinning), tonometry, and anterior chamber.

• Lab tests: Scrape corneal ulcer with sterile spatula or blade and smear on microbiology slides; send for routine cultures (bacteria), Sabouraud’s media (fungi), chocolate agar (H. influenzae, N. gonorrhoeae), Gram stain (bacteria), Giemsa stain (fungi, Acanthamoeba); consider calcofluor white (Acanthamoeba) and acid fast (Mycobacteria) if these entities are suspected.

• Consider corneal biopsy for progressive disease, culture-negative ulcer, or deep abscess (usually fungal, Acanthamoeba, crystalline keratopathy).

• Consider confocal microscopy to identify fungal hyphae and Acanthamoeba cysts.

Prognosis

Depends on organism, size, location, and response to treatment; sequelae may range from a small corneal scar without alteration of vision to corneal perforation requiring emergent grafting. Poor for fungal, Acanthamoeba, and chronic herpes zoster keratitis; herpes simplex and Acanthamoeba commonly recur in corneal graft. Neurotrophic corneas are at risk for melts and perforation.

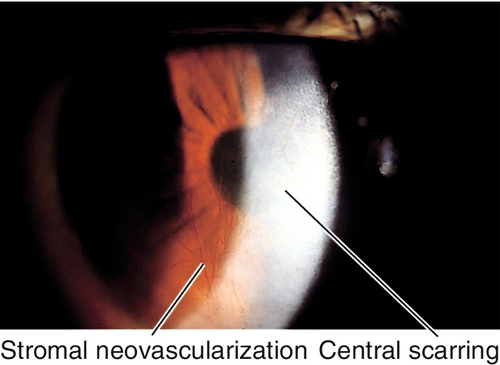

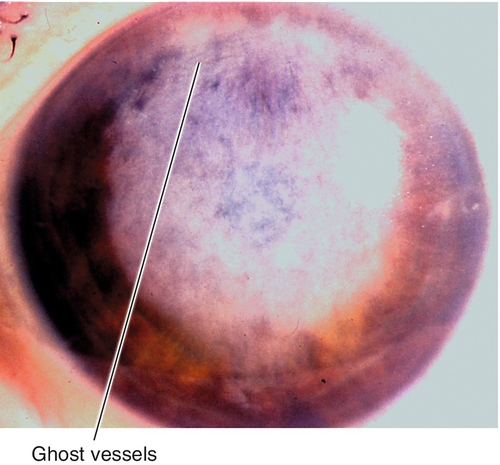

Interstitial Keratitis

Definition

Diffuse or sectoral vascularization and scarring of the corneal stroma due to nonnecrotizing inflammation and edema; may be acute or chronic.

Etiology

Most commonly congenital syphilis (90% of cases), tuberculosis, and herpes simplex; also herpes zoster, leprosy, onchocerciasis, mumps, lymphogranuloma venereum, sarcoidosis, and Cogan’s syndrome (triad of interstitial keratitis, vertigo, and deafness).

Symptoms

Acute

Decreased vision, pain, photophobia, red eye.

Chronic

Usually asymptomatic.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity.

Acute

Conjunctival injection, salmon patch (stromal vascularization), stromal edema, anterior chamber cells and flare, keratic precipitates.

Chronic

Deep corneal haze, scarring, thinning, vascularization, ghost vessels; may have other stigmata of congenital syphilis (optic nerve atrophy, salt-and-pepper fundus, deafness, notched teeth, saddle nose, sabre shins).

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, PPD and controls, and chest radiographs; consider angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE).

• Consider medical and otolaryngology (Cogan’s syndrome) consultation.

Prognosis

Good; corneal opacity is nonprogressive.

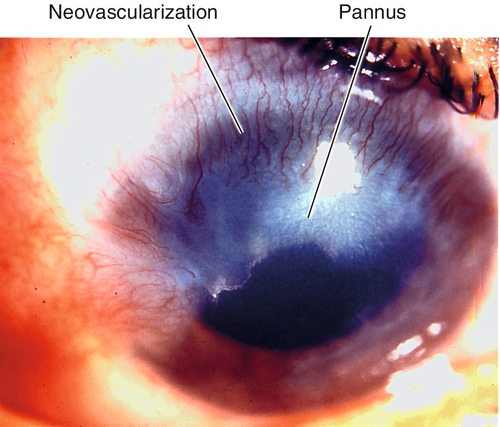

Pannus

Definition

Superficial vascularization and scarring of the peripheral cornea due to inflammation; histologically, fibrovascular tissue between epithelium and Bowman’s layer. Two types:

Inflammatory

Bowman’s layer destruction, with inflammatory cells.

Degenerative

Bowman’s layer intact, with areas of calcification.

Etiology

Trachoma, contact-lens-related neovascularization, vernal keratoconjunctivitis, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis, atopic keratoconjunctivitis, staphylococcal blepharitis, Terrien’s marginal degeneration, ocular rosacea, herpes simplex, chemical injury, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, Stevens–Johnson syndrome, aniridia, or idiopathic.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision if visual axis is involved.

Signs

Corneal vascularization and opacification past the normal peripheral vascular arcade; micropannus (1–2 mm), gross pannus (> 2 mm).

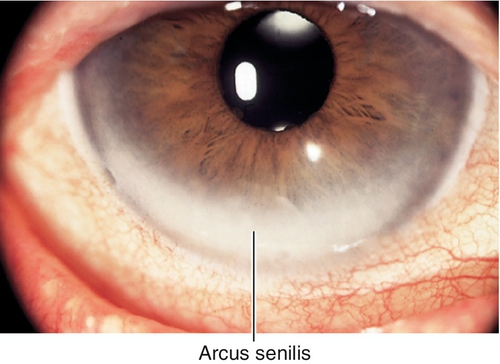

Differential Diagnosis

Arcus senilis, staphylococcal marginal keratitis, phlyctenulosis, Salzmann’s nodular degeneration.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to everting lids, conjunctiva, and cornea.

Prognosis

Good; may progress.

Degenerations

Definition

Acquired lesions secondary to aging or previous corneal insult.

Arcus Senilis

Bilateral, white ring in peripheral cornea; occurs in elderly individuals due to lipid deposition at level of Bowman’s and Descemet’s membranes; clear zone exists between arcus and limbus. Check lipid profile if patient is under 40 years old; unilateral is due to contralateral carotid occlusive disease; arcus juvenilis is the congenital form.

Band Keratopathy

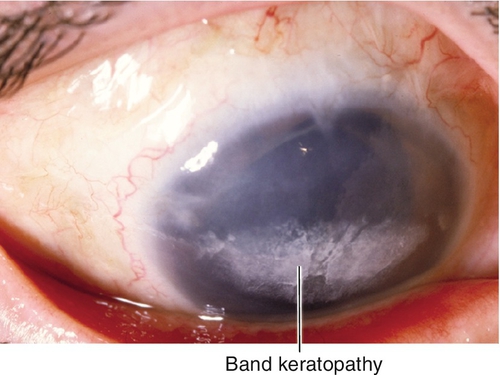

Interpalpebral, subepithelial, patchy calcific changes in Bowman’s membrane; Swiss cheese pattern; due to chronic ocular inflammation (edema, uveitis, glaucoma, interstitial keratitis, phthisis, dry eye syndrome), hypercalcemia, gout, mercury vapors, or hereditary.

Crocodile Shagreen

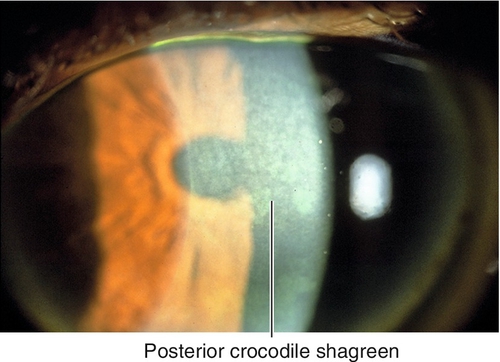

Bilateral, gray-white opacification at the level of Bowman’s layer (anterior) or the deep stroma (posterior); mosaic or cracked ice pattern. Usually asymptomatic.

Furrow Degeneration

Corneal thinning in the clear zone between arcus senilis and the limbus (more apparent than real); perforation is rare; nonprogressive.

Lipid Keratopathy

Yellow-white, subepithelial and stromal infiltrate with feathery edges due to lipid deposition from chronic inflammation and vascularization.

Spheroidal Degeneration (Actinic Degeneration, Labrador Keratopathy, Climatic Droplet Keratopathy, Bietti’s Nodular Dystrophy)

Bilateral, elevated, interpalpebral, yellow, stromal droplets due to sun exposure. Male predilection; associated with band keratopathy.

Salzmann’s Nodular Degeneration

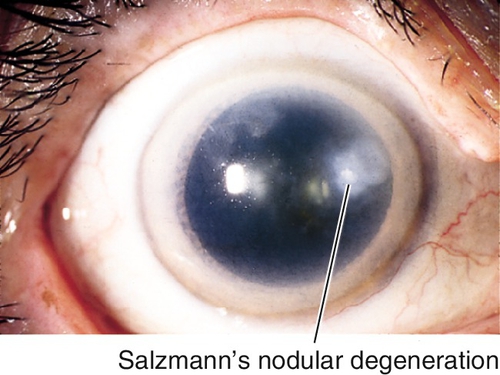

Elevated, usually midperipheral, smooth, opaque, blue-white, subepithelial, hyaline nodules due to chronic keratitis. Female predilection. Causes irregular astigmatism, refractive change.

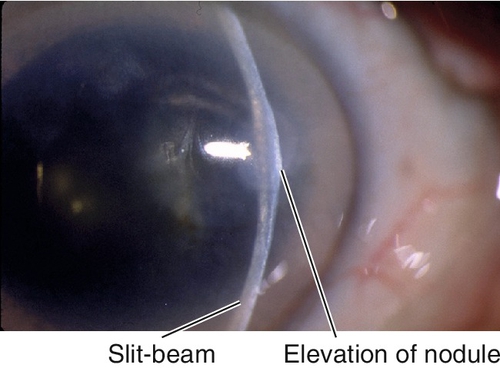

Figure 5-54 Same patient as Figure 5-53, demonstrating elevation of nodule with fine slit-beam.

Terrien’s Marginal Degeneration

Noninflammatory, slowly progressive, peripheral thinning of cornea with pannus; starts superiorly and spreads circumferentially; epithelium intact. Slight male predilection. Causes progressive against-the-rule astigmatism; rarely perforates.

White Limbal Girdle of Vogt

Bilateral, white, needle-like opacities in interpalpebral peripheral cornea; occurs in elderly patients. Two types:

Type I

Calcific (lucid interval at limbus).

Type II

Elastotic (no lucid interval).

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have tearing, photophobia, decreased vision, and foreign body sensation.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, corneal opacity.

Differential Diagnosis

See above, corneal dystrophy, metabolic disease, corneal deposits.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to cornea.

• Consider corneal topography (computerized videokeratography) for Terrien’s marginal degeneration.

Prognosis

Good, most are benign incidental findings; poor for band and lipid keratopathy, because these are progressive conditions secondary to chronic processes.

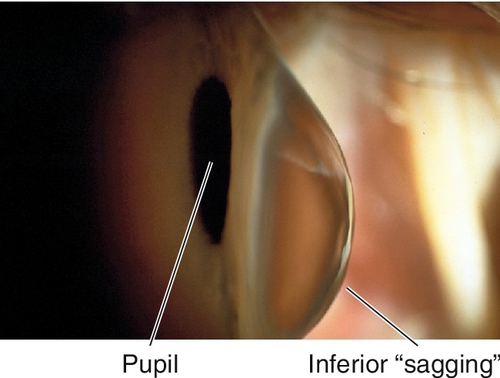

Ectasias

Definition

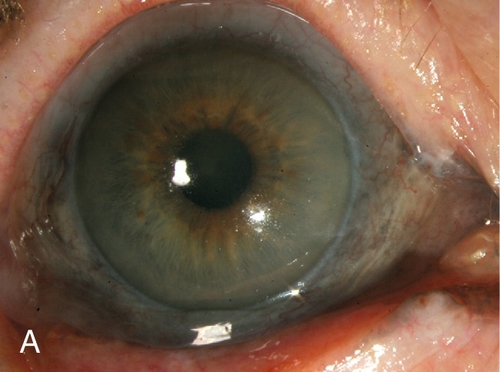

Keratoconus

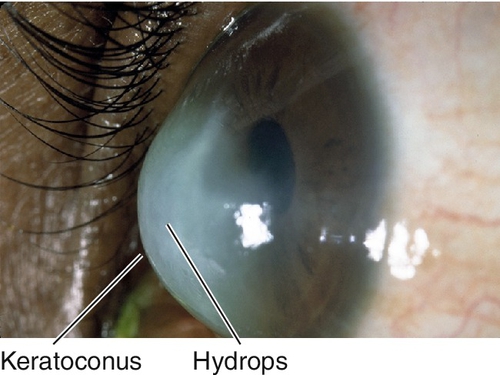

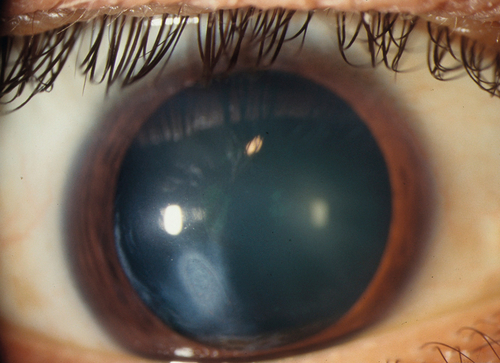

Bilateral, asymmetric, cone-shaped deformity of the cornea due to progressive central or paracentral corneal thinning. Patients develop irregular astigmatism, corneal striae, superficial scarring from breaks in Bowman’s membrane, acute painful stromal edema from breaks in Descemet’s membrane (hydrops). Usually sporadic, but may have positive family history (10% of cases); occurs in up to 0.6% of the population (1 : 2000) and has been reported in up to 10% of individuals in contact lens or refractive surgery clinics; associated with atopy and vernal keratoconjunctivitis (eye rubbing), Down’s syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, and contact lens wear (hard lenses).

Keratoglobus

Rare, globular deformity of the cornea due to diffuse thinning and steepening that is maximal at the base of the protrusion. Sporadic; associated with Ehlers–Danlos syndrome.

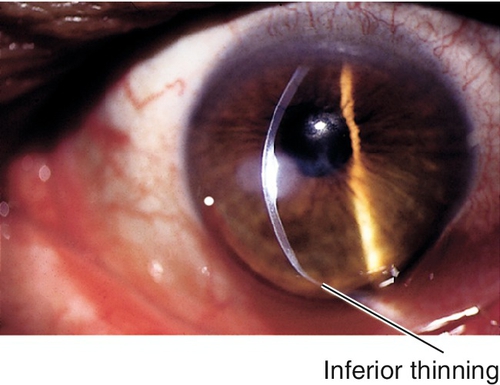

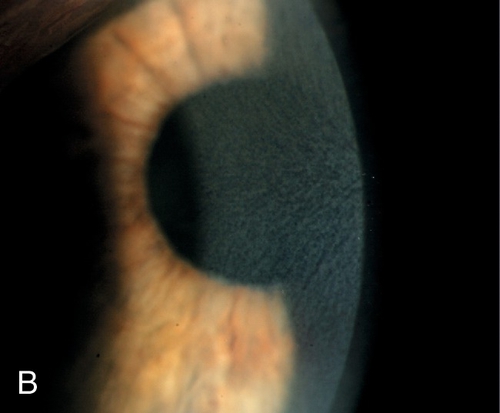

Pellucid Marginal Degeneration

Bilateral, inferior, peripheral corneal thinning (2 mm from limbus) with protrusion above thinned area. Patients develop irregular against-the-rule astigmatism; no scarring, cone, or striae occurs.

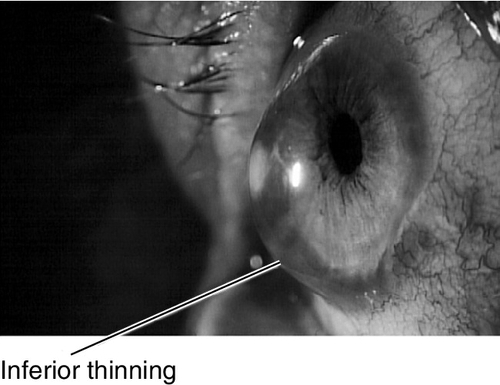

Figure 5-63 Side view of same patient as Figure 5-62 demonstrating protrusion of cornea.

Symptoms

Decreased vision; may have sudden loss of vision, pain, photophobia, tearing, and red eye in hydrops.

Signs

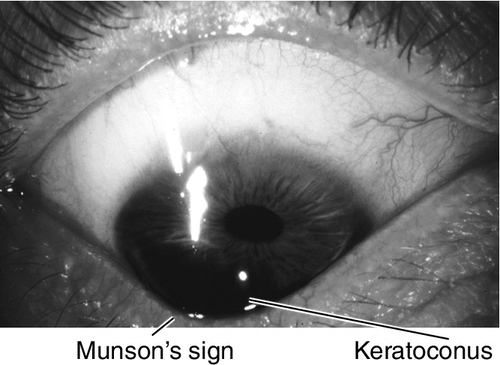

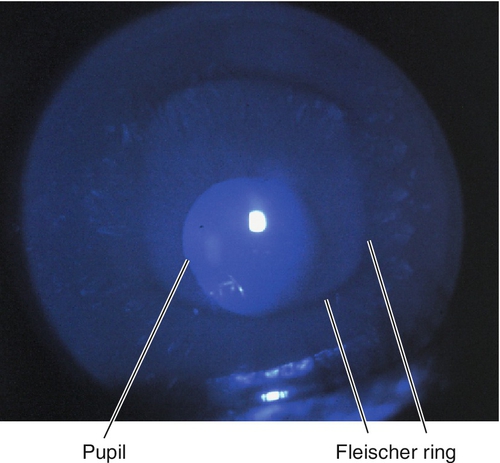

Decreased visual acuity, abnormally shaped cornea, astigmatism, steep keratometry with irregular mires, abnormal corneal topography. In keratoconus, may have central thinning, scarring, Fleischer ring (epithelial iron deposition around base of cone, best seen with blue light), Vogt’s striae (deep, stromal, vertical stress lines at apex of cone), Munson’s sign (protrusion of lower lid with downgaze), and Rizzuti’s sign (triangle of light on iris from penlight beam focused by cone). In keratoconus and pellucid marginal degeneration, may have hydrops (opaque edematous cornea, ciliary injection, and anterior chamber cells and flare).

Differential Diagnosis

See above; Terrien’s marginal degeneration, contact-lens-induced corneal warpage (pseudokeratoconus), corneal topography artifact.

Evaluation

• Corneal topography (computerized videokeratography, CVK): Characteristic pattern of irregular astigmatism (central or inferior steepening in KC, and similar pattern or asymmetric skewed bow-tie pattern in form fruste or KC suspects; inferior claw or lazy-C pattern of steepening in PMD). Three specific CVK parameters have classically been used to aid in the diagnosis of KC (central corneal power > 47.2D, difference in corneal power between fellow eyes > 0.92D, and I–S value [difference between average inferior and superior corneal powers 3 mm from the center of the cornea] > 1.4D). Most CVK instruments have built-in software to identify early and subclinical ectasias, and elevation maps may provide increased sensitivity.

Prognosis

Good; penetrating keratoplasty and DALK have high success rate for keratoconus and keratoglobus.

Congenital Anomalies

Definition

Variety of developmental corneal abnormalities:

Cornea Plana (Autosomal Dominant [AD] or Autosomal Recessive [AR])

Flat cornea (curvature often as low as 20–30D); corneal curvature equal to scleral curvature is pathognomonic; associated with sclerocornea and microcornea; increased incidence of angle-closure glaucoma. Mapped to chromosome 12q.

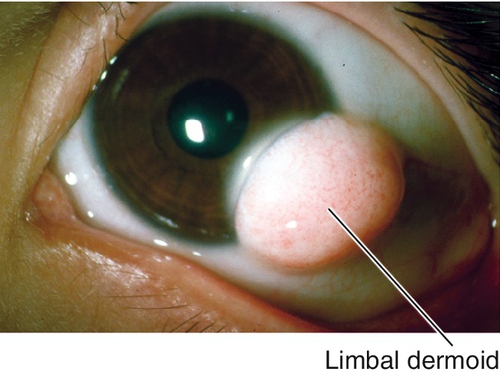

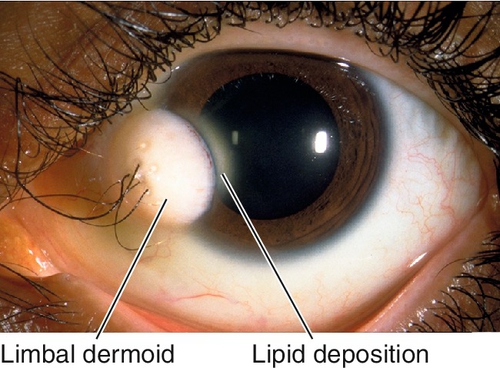

Dermoid

Choristoma (normal tissue in abnormal location) composed of dense connective tissue with pilosebaceous units and stratified squamous epithelium; usually located at inferotemporal limbus, can involve entire cornea. May cause astigmatism and amblyopia; may be associated with preauricular skin tags and vertebral anomalies (Goldenhar’s syndrome).

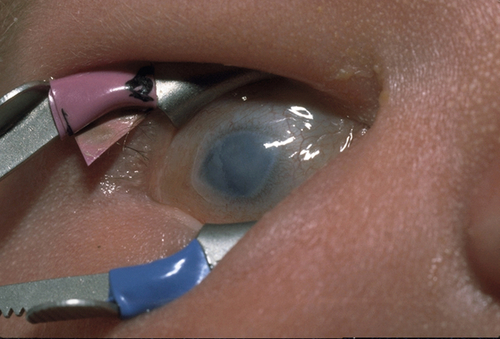

Haab’s Striae

Horizontal breaks in Descemet’s membrane due to increased intraocular pressure in children with congenital glaucoma.

Megalocornea (X-Linked)

Enlarged cornea (horizontal diameter ≥ 13 mm); male predilection (90%). Usually isolated, nonprogressive, and bilateral; associated with weak zonules and lens subluxation.

Microcornea (AD and AR)

Small cornea (diameter < 10 mm); increased incidence of hyperopia and angle-closure glaucoma.

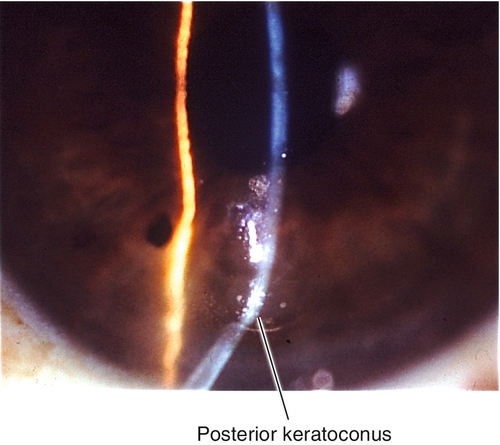

Posterior Keratoconus

Focal, central indentation of the posterior cornea with intact endothelium and Descemet’s membrane; no change in anterior corneal surface. Rare, usually unilateral, and nonprogressive; female predilection.

Sclerocornea

Scleralized peripheral or entire cornea; nonprogressive. 50% sporadic, 50% hereditary (AR more severe); 90% bilateral; 80% associated with cornea plana.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, abnormal corneal size or shape, corneal opacity, edema, or scarring; may have other anterior segment abnormalities (angle, iris, or lens) and increased intraocular pressure.

Differential Diagnosis

• Small cornea: microphthalmos, nanophthalmos.

• Large cornea: congenital glaucoma (buphthalmos).

• Cloudy cornea: interstitial keratitis, birth trauma, metabolic disease, Peter’s anomaly, edema, dystrophy, rubella, staphyloma.

• Posterior keratoconus: internal ulcer of von Hippel (excavation of the posterior cornea with scarring due to focal absence of endothelium and Descemet’s membrane), Peter’s anomaly.

Evaluation

• May require examination under anesthesia.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology.

Dystrophies

Definition

Primary, hereditary, corneal diseases; usually bilateral, symmetric, central, and progressive with early onset.

Anterior (Epithelial and Bowman’s Membrane)

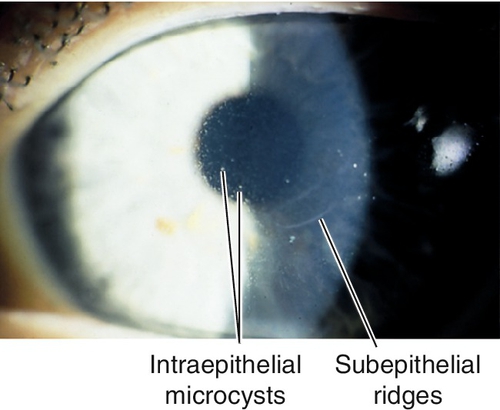

Anterior Basement Membrane Dystrophy (Epithelial Basement Membrane Dystrophy, Map-Dot-Fingerprint Dystrophy, Cogan’s Microcystic Dystrophy) (AD)

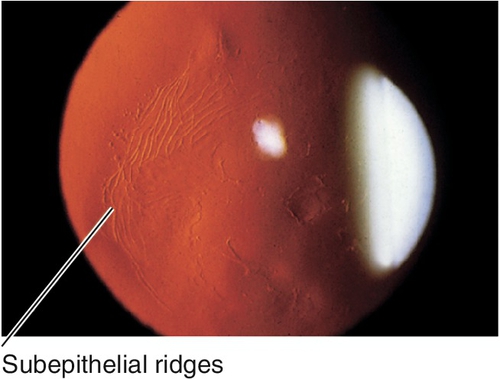

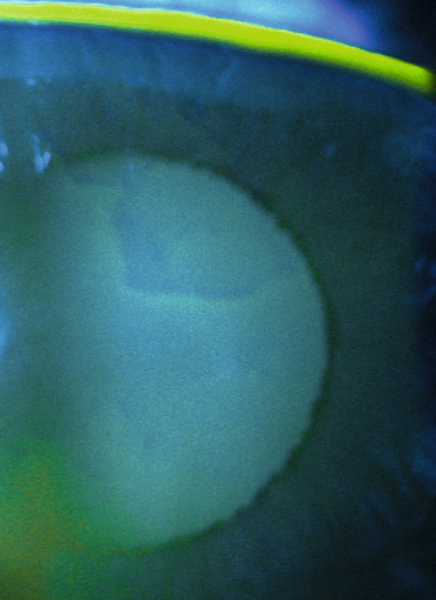

Most common anterior corneal dystrophy. Abnormal epithelial adhesion causes intraepithelial and subepithelial basement membrane reduplication with intraepithelial microcysts (dots) and subepithelial ridges and lines (map-like and fingerprint-like). Ten per cent of patients with anterior basement membrane dystrophy (ABMD) develop recurrent erosions, whereas 50% of patients with recurrent erosions have ABMD; may develop scarring and decreased vision (due to irregular astigmatism) starting after age 30 years. Slight female predilection.

Gelatinous Drop-like Dystrophy (AR)

Subepithelial, central, mulberry-like, protuberant opacity. Composed of amyloid; lack Bowman’s membrane; rare. Decreased vision, photophobia, and tearing occur in first decade.

Meesman Dystrophy (AD)

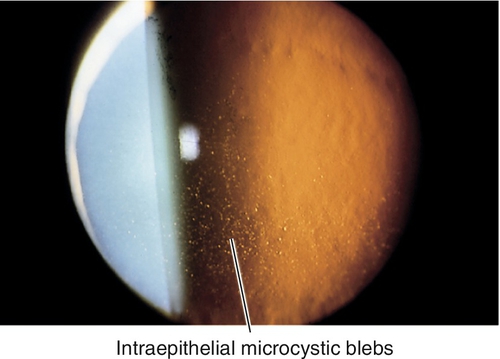

Intraepithelial microcystic blebs concentrated in the interpalpebral zone extending to the limbus; surrounded by clear epithelium. Blebs contain periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive material (“peculiar substance”) and appear as numerous dots with retroillumination. Rare; recurrent erosions common; retain good vision. Mapped to chromosomes 12q (KRT3 gene) and 17q (KRT 12 gene).

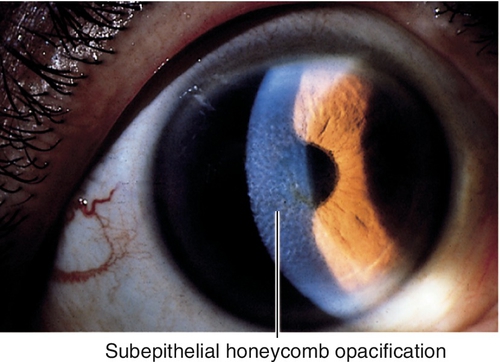

Reis–Bückler Dystrophy (Honeycomb Dystrophy, Thiel–Behnke Dystrophy) (AD)

Progressive subepithelial opacification and scarring of Bowman’s membrane with honeycomb appearance. Recurrent erosions early, usually in the first or second decade; often recurs after penetrating keratoplasty. Mapped to chromosome 5q31 (TGFBI gene).

Stromal

Avellino Dystrophy / Granular Dystropy Type II (AD)

Combination of granular and lattice dystrophies (see below) with discrete granular-appearing opacities; intervening stroma contains lattice-like branching lines and dots (not clear as in granular dystrophy). Composed of a combination of hyaline and amyloid that stains with Congo red and Masson’s trichrome, respectively. Mapped to chromosome 5q31 (TGFBI gene).

Central Cloudy Dystrophy of François (AD)

Small, indistinct, cloudy gray areas in central posterior stroma with intervening clear cracks (like crocodile shagreen, but does not extend to periphery). Nonprogressive; usually asymptomatic.

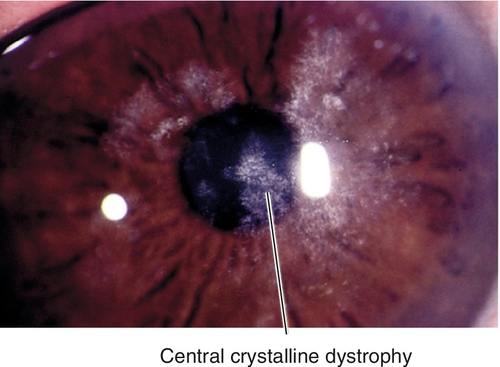

Schnyder’s Central Crystalline Dystrophy (AD)

Central, yellow-white ring of fine, needle-like, polychromatic crystals with stromal haze; also have dense arcus and limbal girdle. Composed of cholesterol and neutral fats that stain with oil-red-O. Very rare and nonprogressive; associated with hyperlipidemia, genu valgum, and xanthelasma; usually asymptomatic. Mapped to chromosome 1p36 (UBIAD1 gene).

Congenital Hereditary Stromal Dystrophy (AD)

Superficial, central, feathery, diffuse opacity; alternating layers of abnormal collagen lamellae. Nonprogressive; associated with amblyopia, esotropia, and nystagmus. Mapped to chromosome 12q21.33 (DCN gene).

Fleck Dystrophy / François–Neetans Fleck (Mouchetée) Dystrophy (AD)

Subtle, gray-white, dandruff-like specks that extend to the limbus. Composed of abnormal glycosaminoglycans that stain with Alcian blue. Can be unilateral and asymmetric; nonprogressive and usually asymptomatic. Mapped to chromosome 2q35 (PIP5K3 gene).

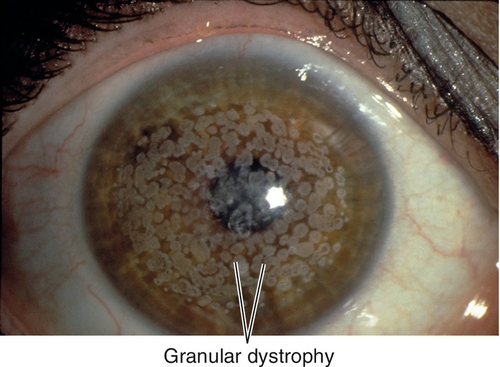

Granular Dystrophy Type I / Groenouw Type I (AD)

Most common stromal dystrophy. Central, discrete, white, breadcrumb- or snowflake-like opacities; intervening stroma usually clear, but may become hazy late; corneal periphery spared. Composed of hyaline that stains with Masson’s trichrome. Recurrent erosions rare; decreased vision late. Mapped to chromosome 5q31 (TGFBI gene).

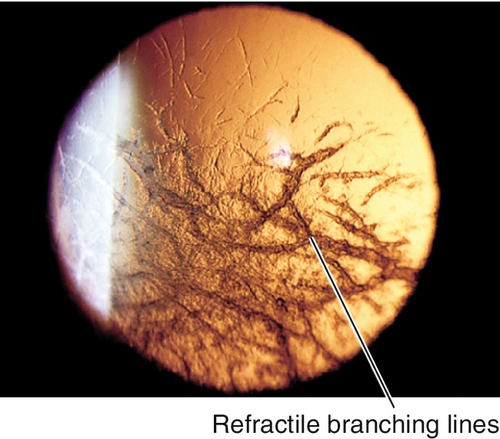

Lattice Dystrophy Type I / Biber–Haab–Dimer Dystrophy (AD)

Refractile branching lines, white dots, and central haze; intervening stroma becomes cloudy, with ground-glass appearance. Composed of amyloid that stains with Congo red. Recurrent erosions common, decreased vision in third decade; often recurs after penetrating keratoplasty. Mapped to chromosome 5q31 (TGFBI gene).

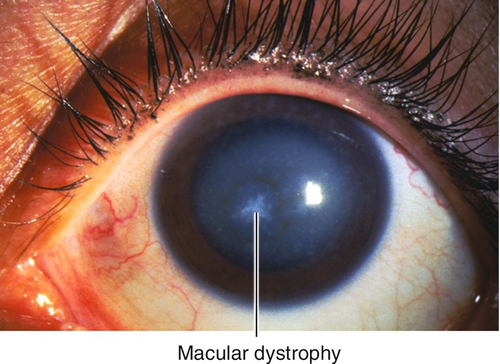

Macular Dystrophy / Groenouw Dystrophy Type II (AR)

Diffuse haze with focal, irregular, gray-white spots that have a sugar-frosted appearance; extends to limbus. Composed of abnormal glycosaminoglycans that stain with Alcian blue. Rare; recurrent erosions occasionally; decreased vision early. Mapped to chromosome 16q22 (CHST6 gene).

Pre-Descemet’s Dystrophy (Deep Filiform Dystrophy) (AD)

Fine, gray, posterior opacities; various morphologies. Composed of lipid. Onset in fourth to seventh decades; usually asymptomatic. Four types: pre-Descemet’s, polymorphic stromal, cornea farinata, and pre-Descemet’s associated with ichthyosis and pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Posterior (Endothelial)

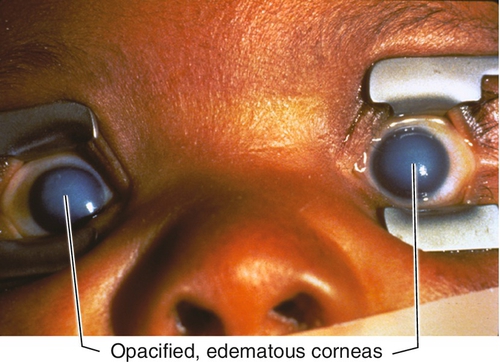

Congenital Hereditary Endothelial Dystrophy (AR > AD)

Opacified, edematous corneas at birth due to endothelial dysfunction; rare. Mapped to chromosome 20p. Two types:

Type 1

More common, autosomal recessive, nonprogressive; no pain or tearing.

Type II

Autosomal dominant, delayed onset (age 1–2 years old), progressive; pain and tearing; may require penetrating keratoplasty. Mapped to chromosome 20 (SLC4A11 gene).

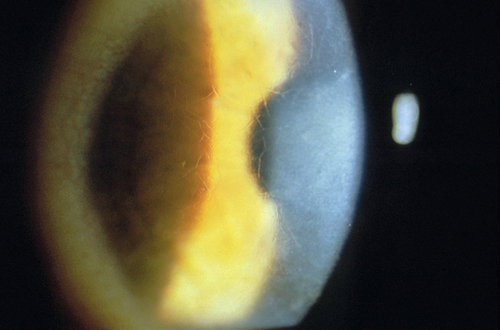

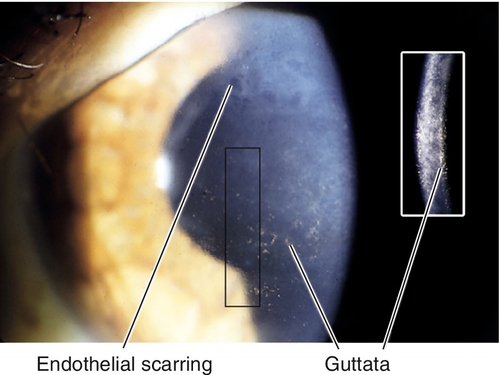

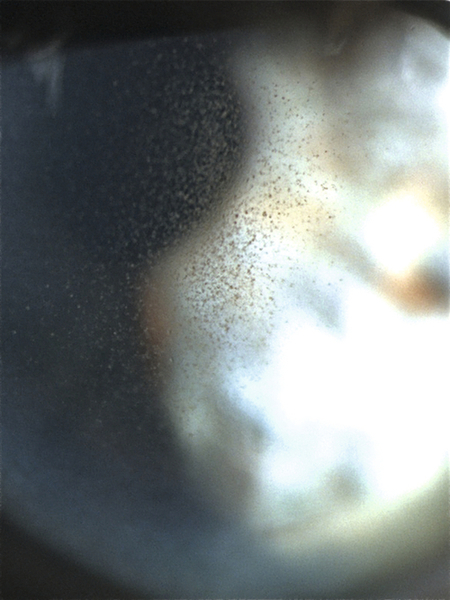

Fuchs’ Endothelial Dystrophy (AD)

Cornea guttata (thickened Descemet’s membrane with PAS-positive excrescences [orange peel appearance]) and endothelial dysfunction. Decreased endothelial cell density, increased pleomorphism, and increased polymegathism; endothelial pigment; early stromal edema, late epithelial edema, bullae, and fibrosis. Female predilection; may have decreased vision (worse in the morning), pain with ruptured bullae, and subepithelial scarring. Mapped to chromosome 18 (TCF4 gene).

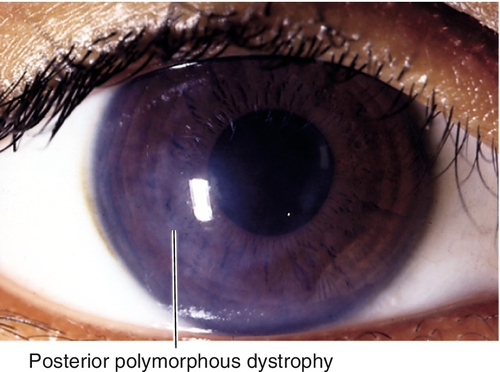

Posterior Polymorphous Dystrophy (AD)

Asymmetric patches of grouped vesicles, scalloped bands, and geographic, gray, hazy areas; epithelial-like endothelium (loss of contact inhibition with proliferation and growth over angle and iris). May develop stromal edema, iris and pupil changes similar to those in iridocorneal endothelial syndrome (see Chapter 7), broad peripheral anterior synechiae, and glaucoma; usually asymptomatic. Mapped to chromosome 20q.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have pain, foreign body sensation, tearing, photophobia, decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, corneal opacities; may have corneal edema or scarring.

Differential Diagnosis

See above, corneal degeneration, corneal deposits, metabolic diseases, interstitial keratitis.

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography if unable to visualize the fundus.

• Consider pachymetry and specular microscopy for Fuchs’ dystrophy.

• Lab tests: Lipid profile for Schnyder’s central crystalline dystrophy.

Prognosis

Usually good; may recur in graft (Reis-Bückler > macular > granular > lattice); may develop glaucoma (posterior polymorphous).

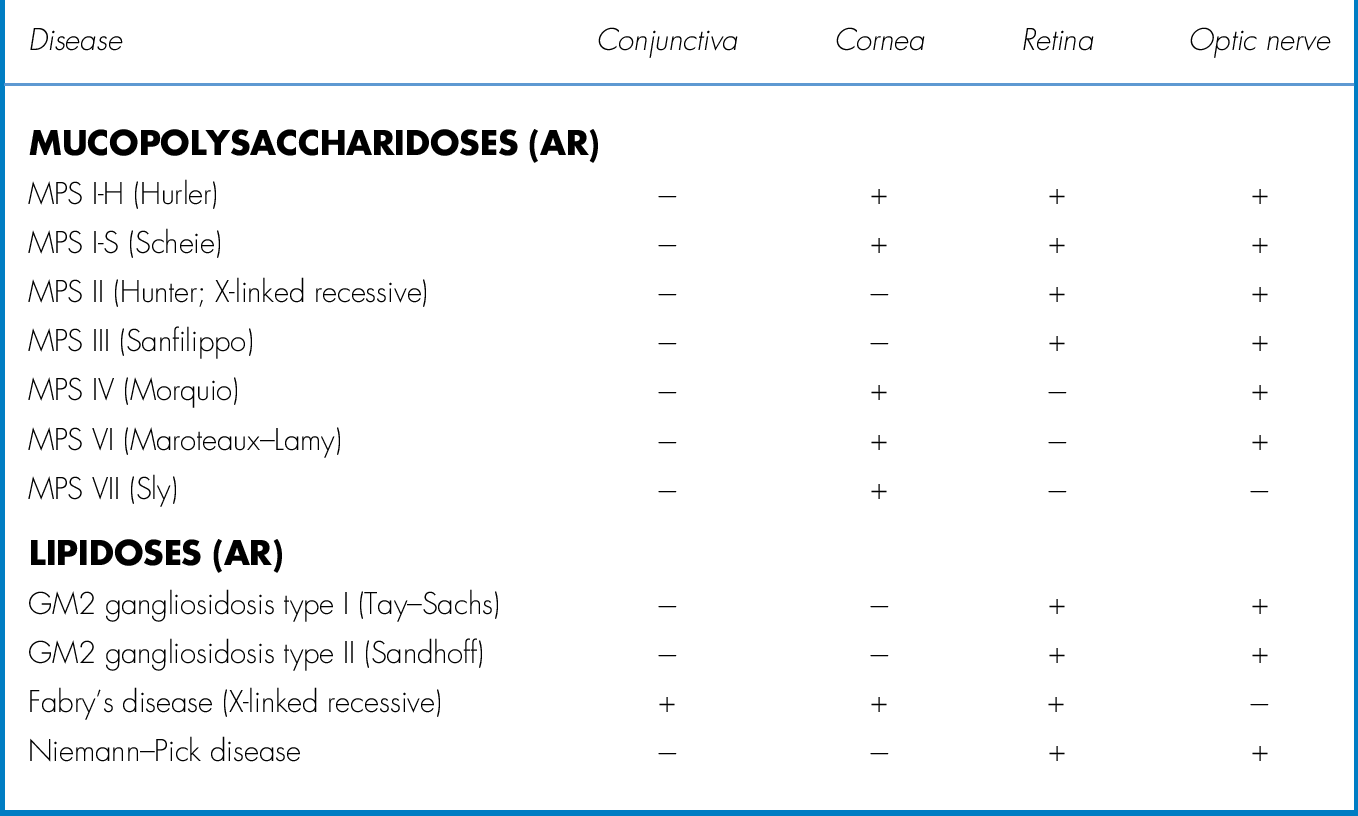

Metabolic Diseases

Definition

Hereditary (AR) enzymatic deficiencies that result in accumulation of substances in various tissues as well as bilateral corneal opacities.

Etiology

Mucopolysaccharidoses, mucolipidoses, sphingolipidoses, gangliosidosis type 1; corneal clouding does not occur in Hunter’s or Sanfilippo’s syndromes.

Symptoms

Decreased vision.

Signs

Decreased visual acuity and corneal stromal opacification; may have nystagmus, cataracts, retinal pigment epithelial changes, macular cherry-red spot, optic nerve atrophy, and other systemic abnormalities.

Differential Diagnosis

See above; congenital glaucoma, birth trauma, congenital hereditary endothelial dystrophy, Peter’s anomaly, sclerocornea, dermoid, interstitial keratitis, corneal ulcer, rubella, staphyloma.

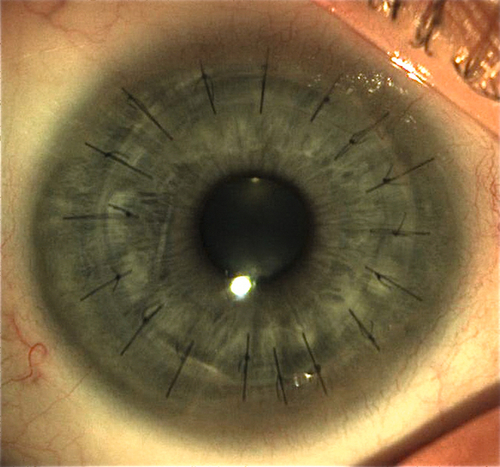

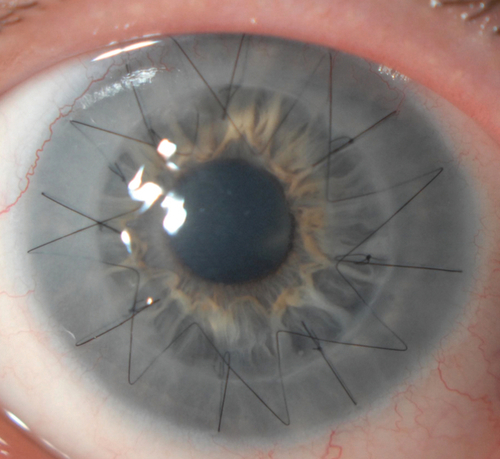

Figure 5-89 DALK in same patient as Figure 5-88 demonstrating clear graft with running and interrupted sutures.

Evaluation

• May require examination under anesthesia.

• Pediatric consultation.

Prognosis

Poor.

Deposits

Definition

Pigment or crystal deposition at various levels of the cornea.

Calcium

Yellow-white deposits in Bowman’s membrane (see Degenerations: Band Keratopathy section).

Copper

Chalcosis

Green-yellow pigmentation of Descemet’s membrane and iris; causes sunflower cataract. Occurs with intraocular foreign body composed of less than 85% copper; pure copper causes suppurative endophthalmitis.

Wilson’s disease

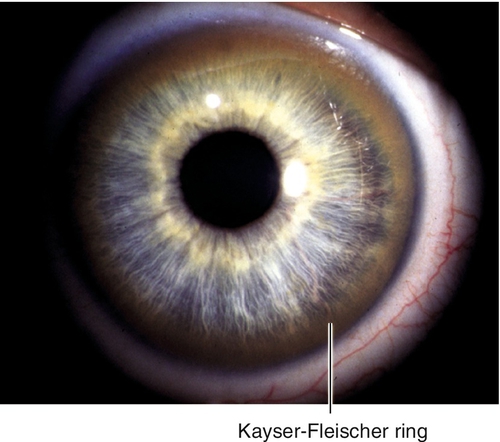

Ninety-five percent have Kayser–Fleischer ring at Descemet’s membrane (brown-yellow-green peripheral pigmentation that starts inferiorly, no clear interval at limbus); best identified by gonioscopy.

Figure 5-90 Copper deposition in a patient with Wilson’s disease, demonstrating peripheral, brown, Kayser–Fleischer ring.

Cysteine (Cystinosis)

Stromal, polychromatic crystals.

Drugs

Epinephrine

Black, conjunctival and corneal adrenochrome deposits.

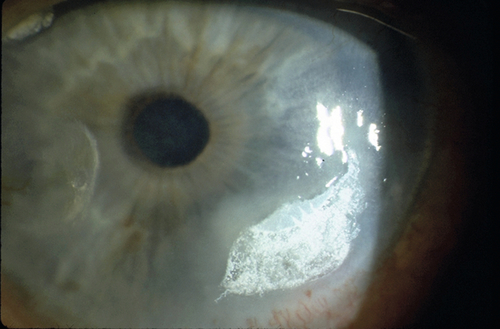

Ciprofloxacin

White precipitate over epithelial defect of corneal ulcer; dose related (i.e., topical drops every 1–2 hours).

Gold (chrysiasis)

Deposits in conjunctival and stromal periphery; dose related.

Mercury

Preservative in drops causes orange-brown band in Bowman’s membrane.

Silver (argyrosis)

Conjunctival and deep stromal deposits.

Thorazine or stelazine

Brown, stromal deposits; also anterior subcapsular lens deposits.

Immunoglobulin (Multiple Myeloma)

Stromal deposits (also occur in Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and benign monoclonal gammopathy).

Iron

Blood staining

Stromal deposits, from hyphema.

Ferry line

Epithelial deposits, under filtering bleb.

Fleischer ring

Epithelial deposits, at base of cone in keratoconus.

Hudson–Stahli line

Epithelial deposits, across inferior one-third of cornea.

Siderosis

Stromal deposits, from intraocular metallic foreign body.

Stocker line

Epithelial deposits, at head of pterygium.

Ink or Chemical Dye

Corneal tattooing

Black stromal deposits; may be used for treatment of corneal opacities and mature cataracts (cosmetic) or glare from iris defects (therapeutic).

Lipid or Cholesterol (Dyslipoproteinemias)

Hyperlipoproteinemia

Arcus in types 2, 3, and 4.

Fish-eye disease (partial LCAT deficiency)

Diffuse corneal clouding, denser in periphery. Mapped to chromosome 16q22 (LCAT gene).

Lecithin–cholesterol acyltransferase (LCAT) deficiency

Dense arcus and diffuse, fine, gray, stromal dots. Mapped to chromosome 16q22 (LCAT gene).

Tangier’s disease (familial high-density lipoprotein deficiency)

Diffuse or focal, small, deep, stromal opacities. Mapped to chromosome 9q31 (ABCA1 gene).

Melanin

Krukenberg spindle

Endothelial deposits, central vertical distribution in pigment dispersion syndrome.

Scattered endothelial pigment

Ingested by abnormal endothelial cells (Fuchs’ dystrophy).

Tyrosine (Tyrosinemia) Type II / Richner–Hanhart Syndrome

Epithelial and subepithelial pseudodendritic opacities; may ulcerate and cause vascularization and scarring. Deficiency of the enzyme tyrosine aminotransferase, encoded by the gene TAT.

Urate (Gout)

Epithelial, subepithelial, and stromal, fine, yellow crystals; may form brown, band keratopathy with ulceration and vascularization.

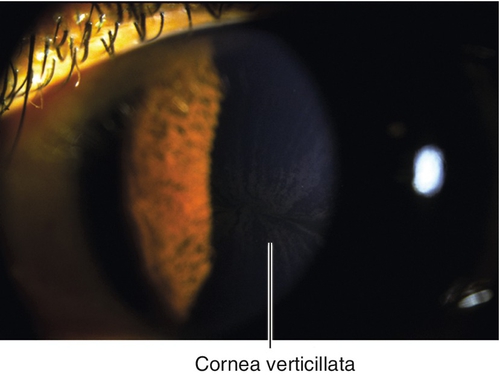

Verticillata (Vortex Keratopathy)

Brown, epithelial, whorl pattern involving inferior and paracentral cornea; occurs in Fabry’s disease (X-linked recessive) including carriers (women); also due to amiodarone, chloroquine, indometacin, chlorpromazine, or tamoxifen deposits.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have photophobia and, rarely, decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, corneal deposits; may have iris heterochromia (siderosis and chalcosis), cataract (Wilson’s disease, intraocular metallic foreign body, tyrosinemia), corneal ulcer (tyrosinemia, gout).

Differential Diagnosis

See above; Dieffenbachia plant sap, ichthyosis (may have fine, white, deep, stromal opacities), hyperbilirubinemia, foreign bodies (i.e., blast injury).

Evaluation

• Electroretinogram (ERG) for intraocular metallic foreign body.

• Medical consultation for systemic diseases.

Prognosis

Good except for siderosis, chalcosis, Wilson’s disease, and multiple myeloma.

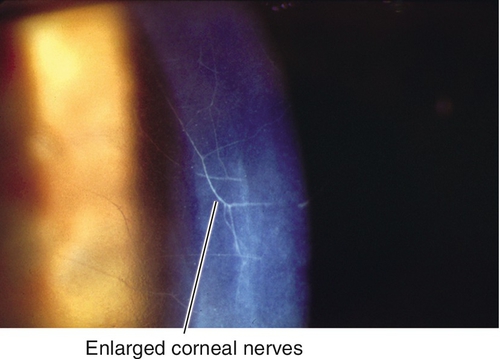

Enlarged Corneal Nerves

Definition

Prominent, enlarged corneal nerves.

Etiology

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIb (MEN-IIb), leprosy, Fuchs’ dystrophy, amyloidosis, keratoconus, ichthyosis, Refsum’s syndrome, neurofibromatosis, congenital glaucoma, trauma, posterior polymorphous dystrophy, and idiopathic.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic.

Signs

Prominent, white, branching, lines in the cornea.

Differential Diagnosis

See above; lattice dystrophy.

Evaluation

• Medical consultation for systemic diseases.

Prognosis

Enlarged nerves are benign; underlying etiology may have poor prognosis (i.e., MEN-IIb).

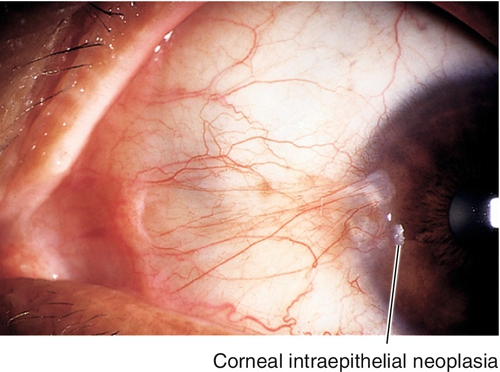

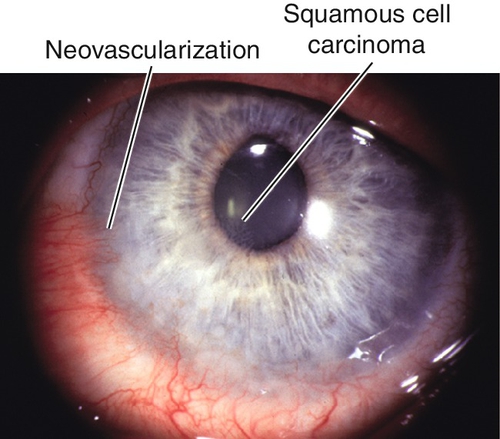

Tumors

Definition

Corneal intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) or squamous cell carcinoma involving the cornea; usually arises from conjunctiva near limbus (see Chapter 4).

Epidemiology

Usually unilateral; more common in elderly, Caucasian males; associated with ultraviolet radiation, human papilloma virus, and heavy smoking; suspect AIDS in patients < 50 years of age.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have foreign body sensation, red eye, decreased vision, or notice growth (white spot) on cornea.

Signs

Gelatinous, thickened, white, nodular or smooth, limbal or corneal mass with loops of abnormal vessels.

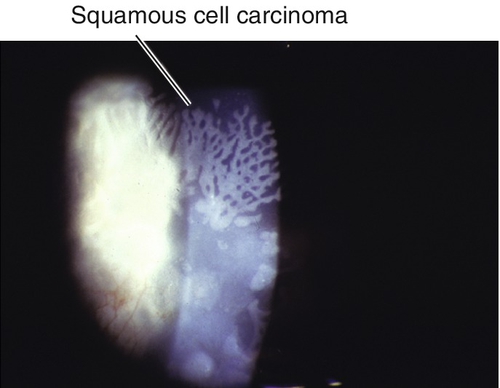

Figure 5-100 Same patient as Figure 5-99 demonstrating a close-up of the white gelatinous lesion.

Differential Diagnosis

Pinguecula, pterygium, pannus, dermoid, Bitot’s spot, papilloma, pyogenic granuloma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia ([PEH] benign, rapid, conjunctival proliferation onto cornea), hereditary benign intraepithelial dyskeratosis ([HBID] elevated white-gray interpalpebral conjunctival plaques with abnormal vessels; may involve cornea and affect vision; oral mucosa also affected; occurs in American Indians from North Carolina; AD, mapped to chromosome 4q35).

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to conjunctiva and cornea.

• MRI to rule out orbital involvement if suspected.

• Medical consultation and systemic workup.

Prognosis

Depends on extent and ability to completely excise. Intraocular spread, orbital invasion, and metastasis are rare; recurrence after excision is < 10%; mortality rate of up to 8%.