27

Contraception

Introduction

Over the last 70 years, the global population has tripled from 2 billion to over 6 billion. According to the median variation of the United Nations’ Review of World Population Prospects, 2010, the world population is expected to increase from 6.9 billion in 2011 to 9.3 billion in 2050 and to reach 10.1 billion by 2100. The current ‘ecological footprint’, the productive area of earth necessary to support the lifestyle of an individual, is approximately double the level that is sustainable long term. Many of the world’s population already does not have enough food to eat, the number of people experiencing water shortages is continuing to rise and is estimated to reach between 500 million and 3 billion by 2050. Widely available, effective contraception has a central role to play in limiting population expansion.

Contraception also has the potential to make a contribution to maternal and child survival. It has been estimated that family planning could save the lives of 3 million children a year by helping women to space births at least 2 years apart, and to bear children during their healthiest reproductive years. When women have the ability to space their births, they are better able to recover from nutritional depletion, blood loss and reproductive-system damage, allowing them to have healthier babies. Many women in the developing world would like to space or limit their births, but do not have access to family planning information or services.

Reproductive health programmes aid in the prevention of HIV transmission and other sexually transmitted diseases. Half of all new HIV infections in the developing world are among women and nearly 10% are among infants and children.

The provision of appropriate contraception is arguably one of the most important branches of medicine today worldwide. In the UK, it is estimated that for every £1 spent on contraception, £14 is saved for the NHS. A wide variety of effective contraceptive methods are available, but there is no ‘ideal’ contraceptive and choice must be based on the balance of risks and benefits of each method for each individual. For most women, the use of contraception is safe, but there are limited data on the use of contraception by women with certain medical conditions. In view of this, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed Medical Eligibility Criteria, which provide evidence-based recommendations to facilitate the safe use of contraception without imposing unnecessary medical restrictions. A UK version is available (www.fsrh.org.uk) and the categories used to define risk are summarized in Table 27.1.

Table 27.1

UKMEC categories

| UKMEC category | Definition |

| UKMEC 1 | A condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method |

| UKMEC 2 | A condition for which the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks |

| UKMEC 3 | A condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the methoda |

| UKMEC 4 | A condition which represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used |

a The provision of a method to a woman with a condition given a UKMEC category 3 requires expert clinical judgement and/or referral to a specialist contraceptive provider, since use of the method is not usually recommended unless other methods are not available or not acceptable.

Defining ‘contraceptive failure’ is not easy, as it depends on the population studied: studies on a young population will suggest a higher failure rate than in an older group, as fertility is higher in younger people. Caution is therefore required when interpreting relevant figures. The ‘method’ failure includes the inherent risk of failure providing the method is used correctly. It is quantified in the units per 100 woman-years (HWY), the number of women who would become pregnant if 100 of them used that method of contraception for 1 year. ‘User’ failure is the failure rates when the method is not used correctly (e.g. missed pills, late injections, drug interactions). If used consistently and correctly, hormonal contraceptives (combined hormonal method, progestogen-only pills, injectable, implant and intrauterine system) and the non-hormonal methods (copper intrauterine device, male and female sterilization) are more than 99% effective in preventing pregnancy. These methods, as well as emergency contraception, barrier methods and natural family planning methods, are described in this chapter. Evidence-based guidance on all methods of contraception and the use of contraception in specific groups or situations is available on the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare website (www.fsrh.org.uk).

Methods of contraception

Contraception can be considered as either hormonal (pills, patch, intravaginal ring, injectable, subdermal and the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system, LNG-IUS) or non-hormonal (copper intrauterine device, Cu-IUD, barrier methods, sterilization, lactational amenorrhoea method and natural family planning). UK national statistics show that oral contraception remains the most popular method used by women of reproductive age with sterilization used by older women. Increasingly popular are the so-called long acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods, which include subdermal implants and both copper and levonorgestrel intrauterine methods. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on LARC indicate that these methods are very cost-effective in the prevention of pregnancy. With long duration of use (between 3 and 10 plus years of use depending on the method chosen and the age at insertion), low user failure rates, good satisfaction rates and high efficacy they are becoming increasingly popular in the UK.

Combined oestrogen–progestogen methods (pills, transdermal patch and intravaginal ring)

Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHC) work primarily by inhibiting ovulation via the hypothalamo–pituitary–ovarian axis to reduce luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone. In addition, cervical mucus is less favourable to sperm penetration and the endometrium is more atrophic. Most data on the use and safety of CHC relates specifically to the combined oral contraceptive pill (COC). This evidence is extrapolated to the transdermal patch and intravaginal ring, as they also contain oestrogen and progestogen.

Most currently available COC pills contain ethinyloestradiol (EE) and progestogens (synthetic progesterone), which include levonorgestrel and norethisterone (second generation), desogestrel and gestodene (third generation) and drospirenone (fourth generation). All oestrogen-containing COCs increase the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) above the background risk of 4–5 per 10 000 woman years among women not using a COC. This background rate is almost 10-fold higher than previously recognized, which means that the magnitude of additional risk of VTE associated with COCs is less than previously considered. In the past, studies have suggested differing VTE risk associated with different COCs, depending on the type of progestogen. However, in general, the risk of VTE in COC users appears to be double the risk of VTE in non-COC users. The risk is greatest in the first few months after initiating the COC and the risk falls to that of non-users within weeks of discontinuation. Nevertheless, the absolute risk for VTE is very small (Table 27.2). Risk factors for VTE must be considered when counselling women regarding COC use.

Table 27.2

Risk of venous thromboembolism associated with COC use

| Absolute risk of VTE per 10 000 woman-years | Circumstance |

| 4–5 | For women not using COC and not pregnant |

| 9–10 | For women using a COC |

| 29 | For women who are pregnant |

| 300–400 | For women who are immediately postpartum |

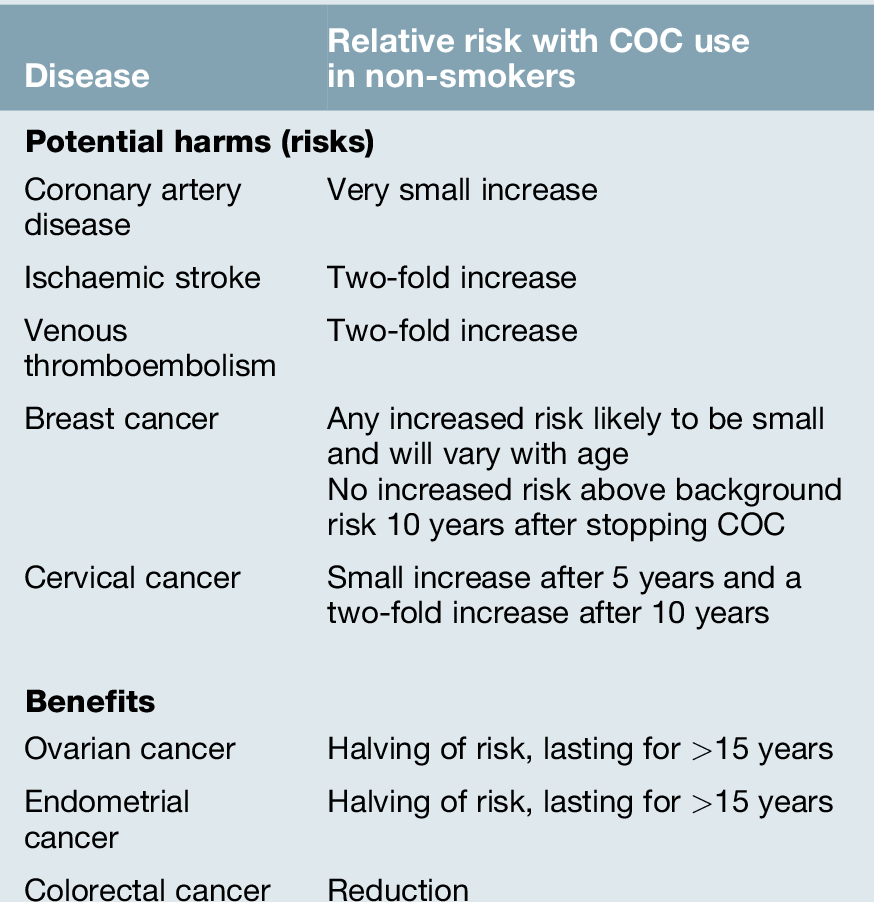

Women considering the COC should be informed of the potential risks and benefits associated with use (Table 27.3). Combined hormonal contraception is safe for most women, most of the time. Indeed, a non-smoker may safely continue with COC use to age 50 years if she has no contraindications for use. Deaths in COC users over 35 years of age are eight times more common in smokers than non-smokers. It is recommended that women who continue to smoke at the age of 35 years should use an alternative form of contraception (UKMEC category 3 if aged ≥ 35 years and smoking < 15 cigarettes/day or UKMEC category 4 if smoking ≥ 15 cigarettes/day). The use of COC may pose an unacceptable health risk in women with cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, stroke, hypertension, venous thromboembolism), liver disease (severe cirrhosis, active viral hepatitis, tumours) or migraine with aura at any age.

How to take the COC

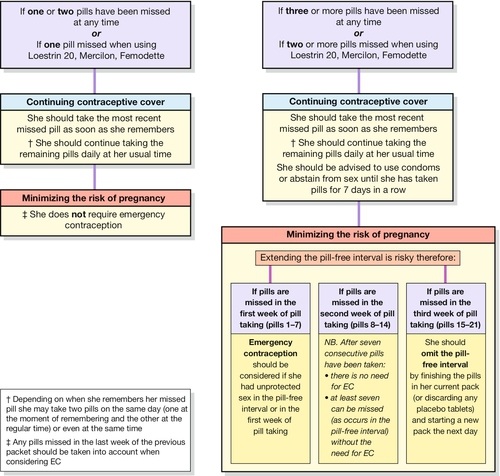

Usually a fixed dose monophasic pill containing 20–35 μg of EE and a progestogen is used. There are no proven benefits of a biphasic or triphasic COC (where doses of the constituent hormones are varied) over a monophasic pill. A COC can be started up to and including day 5 of the menstrual cycle to provide immediate contraceptive protection. If started after this time, condoms or abstinence is advised for the next 7 days. Most COC packages contain 21 active tablets: one tablet is taken daily for 21 consecutive days, followed by a 7-day pill-free interval. A withdrawal bleed usually occurs in the pill-free interval due to the withdrawal of hormones which induces endometrial shedding. Women should be encouraged to take COCs daily at or around the same time every day. Missed pill advice is summarized in Figure 27.1. In general, one pill can be missed at any time in the packet without loss in efficacy or the need to use barrier contraception.

Drug interactions

Liver enzyme-inducing drugs (such as carbamazepine, some antiretrovirals, griseofulvin, rifampicin and the over the counter herbal medicine St John’s Wort) accelerate the hepatic breakdown of contraceptive steroids, thus potentially reducing the efficacy of the COC. The options for women using liver enzyme-inducing drugs long term who wish to continue with COC use is to increase the dose of EE to 50–60 μg/day (usually taking two pills per day), although use in this manner is unlicensed. In addition, it is recommended to reduce the pill-free interval. Condoms should also be used, however, as there are no studies to identify the correct dose of COC required to maintain contraceptive efficacy in these situations. The antibiotic rifampicin and the antifungal griseofulvin are potent liver enzyme inducers and advice is as for other liver enzyme-inducing drugs but in addition barrier contraception is advised for at least 4 weeks after cessation of these liver enzyme-inducing medications. An alternative is to use a method of contraception, which is unaffected by liver enzyme-inducing medication (such as a progestogen-only injectable, the LNG-IUS or a copper intrauterine device, Cu-IUD).

COCs can affect the levels of some drugs. Serum levels of the anticonvulsant lamotrigine are reduced with COC use. Lamotrigine levels can increase in the pill free week or when stopping COC.

Gut bacterial flora is involved in the breakdown of EE in the large bowel; this facilitates the secondary reabsorption of EE via the enterohepatic circulation. Antibiotics commonly alter this bowel flora and were considered to have the potential to reduce the secondary reabsorption of EE. However, new advice form the FSRH and the British National Formulary (BNF) is that women using combined hormonal methods who start a (non-liver enzyme inducing) antibiotic do not require additional contraceptive protection.

Follow-up

A 12-month supply of COC can be given at the first visit, but for some women a follow-up at 3 months may be appropriate to assess any problems and provide re-instruction if necessary. Blood pressure should be assessed annually, but women should be encouraged to attend at any time if problems arise. The pill should be discontinued if any potentially serious side-effects occur (e.g. chest pain, leg pain or swelling). Follow-up visits are also an opportunity to carry out other well-woman screening (e.g. blood pressure, cervical cytology).

The COC should be stopped and an alternative method used at least 6 weeks before any planned major surgery where immobilization is expected. If women are travelling to altitudes > 4500 m for more than 1 week, changing to an EE free method may be advised.

Combined hormonal contraceptive patch

The risks and benefits associated with transdermal patch (Evra®) use are as described as for the COC (Table 27.3). A patch can be applied to the abdomen, buttock or thigh on the same day each week for three consecutive weeks. This is followed by a patch-free week, during which time there is endometrial shedding and a withdrawal bleed. The transdermal patch should be changed every 7 days, although a single patch will provide effective contraceptive protection for up to 9 days. As for the COC, the transdermal patch can be started up to and including day 5 of the menstrual cycle to provide immediate contraceptive protection. If started after this time, condoms or abstinence is advised for the next 7 days.

Combined hormonal intravaginal contraceptive ring

The risks and benefits associated with intravaginal ring (Nuvaring®) use are as described for the COC (Table 27.3). The intravaginal ring is associated with serum concentrations of EE of only 15 μg. The ring is inserted into the vagina on the same day each month and is retained for 3 weeks. This is followed by a ring-free week, during which time the endometrium sheds and there is a withdrawal bleed. Once inserted above the pelvic floor it is not felt and it does not need to be removed during intercourse. As for the COC, the intravaginal ring can be inserted up to and including day 5 of the menstrual cycle to provide immediate contraceptive protection. If started after this time, condoms or abstinence is advised for the next 7 days.

Progestogen-only contraception

Progestogen-only contraception (pills, injectables, subdermal implant and the LNG-IUS) avoids the potential increased risks attributed to oestrogen. Most progestogen-only methods are associated with a disturbance in the bleeding pattern and this is often the main reason for discontinuation of these otherwise very effective methods. Other side-effects have been reported (abdominal bloating, weight changes, acne, headaches and mood changes) but few have been objectively related to progestogen use.

Drug interactions

The effect of liver enzyme-inducing drugs on the metabolism of progestogens is similar to that for oestrogens. This reduces the efficacy of a progestogen-only pill or subdermal implant and alternative methods of contraception are recommended. The progestogen-only injectable depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) and the LNG-IUS, however, are not affected by liver enzyme inducing medication. The dose of MPA in injectable contraception is sufficient to provide contraceptive protection by inhibition of ovulation and the usual 12-week injection interval can be maintained. For women using the LNG-IUS, the progestogen dose is delivered directly to the uterine cavity having a direct local endometrial contraceptive effect. This direct effect is not reduced by drugs which induce liver enzymes.

Progestogen is not reabsorbed from the large bowel and the efficacy of progestogen-only contraception is not reduced by (non-liver-enzyme-inducing) antibiotics.

Progestogen-only pills (POPs)

Traditional POPs (those containing levonorgestrel or norethisterone) and a newer POP (containing desogestrel) are currently available in the UK. Although POPs are suitable for most women, they are often used by women for whom a COC is contraindicated (e.g. when breastfeeding, for women over the age of 35 years who smoke or for women of any age who have migraine with aura). All POPs thicken cervical mucus, thus preventing sperm penetration into the upper reproductive tract and this is the primary mode of action of POPs. In addition, some POPs also inhibit ovulation, although not in every cycle. Traditional POPs inhibit ovulation in up to 60% of cycles and the desogestrel-only pill inhibits ovulation in up to 97% of cycles. A POP should be taken at or around the same time every day without a pill-free interval. A POP can be started up to and including day 5 of the menstrual cycle (within 7 days of a termination of pregnancy or up to day 21 postpartum) to provide immediate contraceptive protection. If started at other times, additional contraceptive protection, such as condoms, is required for the first 48 h. A traditional POP is late if taken ≥ 3 hours after when it was due to be taken; the desogestrel-only pill is late if > 12 h has elapsed. Contraception from intercourse prior to the missed pill is provided but barrier methods are recommended until two consecutive pills have been taken, by which time the cervical mucus effect preventing sperm penetration is maximal again.

Progestogen-only injectable contraception

The most widely used progestogen-only injectable in the UK is depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA), which is licensed to be given as an intramuscular injection every 12 weeks. The primary mode of action of progestogen-only injectables is inhibition of ovulation. Unpredictable bleeding is common in the initial months of use but usually settles and up to 70% of women are amenorrhoeic at 1 year of use. Studies have suggested a delay in return to fertility following cessation of DMPA compared with other contraceptive methods, but no actual reduction in fertility. This is possibly due to the serum levels of MPA, which in some women can still be detected between 6 and 9 months after a single injection, and for some women, in concentrations sufficient to inhibit ovulation.

A reversible loss of bone mineral density occurs with DMPA use. Most of this bone loss is in the initial 2 years of use and thereafter, there is no further loss. There is no indication to consider DEXA bone scans routinely in women using DMPA, even with long-term use. Serum concentrations of oestrogen in women using DMPA are similar to concentrations seen in the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle and therefore women are not hypo-oestrogenic. There is no apparent increase in risk of fracture and moreover, bone mineral density recovers after cessation of DMPA use. There are few long-term data on the use of DMPA in women under the age of 18 years, who have yet to achieve peak bone density. Nevertheless, after counselling, women aged under 18 years can use DMPA (UKMEC 2, benefits outweigh risk). Women can use DMPA up to the age of 50 years, at which time an alternative method should be used. Women should be counselled about the risks and benefits of DMPA and lifestyle factors, which may also be linked to bone loss such as smoking and this should be reassessed every second year of continuing use. Weight gain is a recognized effect of DMPA use.

Other progestogen-only methods of contraception include the progestogen-only emergency contraceptive, subdermal implants and the LNG-IUS, which are discussed further below.

Long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARC)LARC methods include subdermal implants and intrauterine contraceptives. These methods are very effective in pregnancy prevention and are highly cost-effective.

Progestogen-only subdermal implants

This is a single subdermal etonogestrel implant or rod (Nexplanon®) made from a non-biodegradable polymer, which contains an active slow-release progestogen formulation, and is about the size of a matchstick. The implant is licensed to provide contraception for up to 3 years. Changes in bleeding patterns are common and discontinuation due to this is common (up to 43% within 3 years). Up to 20% of users will have no bleeding, but almost 50% will have infrequent, frequent or prolonged bleeding. These bleeding patterns may not settle with time. There is no evidence of a causal association between the use of the implant and weight change, mood change, loss of libido or headache. Health professionals who insert and remove progestogen-only implants should be appropriately trained and insertion is intended to render the implant palpable beneath the skin. Barium sulphate is added to the implant so that if an implant cannot be palpated, an X-ray of the upper arm can identify the implant’s location and facilitate its removal.

Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS)

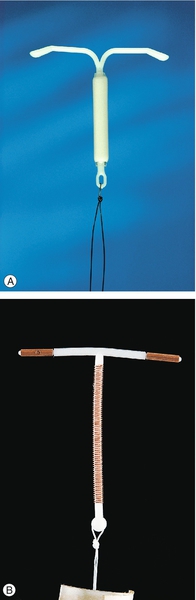

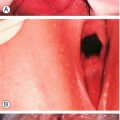

The LNG-IUS (Mirena®) offers a highly effective and reversible contraceptive method (Fig. 27.2A). It is licensed for 5 years’ use as contraception or as a treatment for heavy menstrual bleeding. (It is also licensed for up to 4 years’ use as the progestogenic component of hormone replacement therapy.) Failure rates for 5 years’ use are low (1%). The LNG-IUS works primarily by its effect on the endometrium, preventing implantation. In addition, effects on cervical mucus reduce sperm penetration. Ovulation may be inhibited in up to 25% of women. Irregular bleeding with the LNG-IUS is common in the first few months after insertion but often settle by 6 months after insertion. Menstrual loss is reduced by an average of 90% at 12 months with 20% of women experiencing amenorrhoea. Systemic side-effects due to absorption of levonorgestrel are often mild and usually settle with time. For women who have the device inserted after the age of 45 years, the LNG-IUS may be continued until the menopause is confirmed or until the age of 55 years, at which time the majority of women are postmenopausal. The adverse effects and complications associated with insertion – including expulsion, perforation and infection – are as for a copper intrauterine device (see below).

Non-hormonal contraception

Copper intrauterine devices (Cu-IUDs)

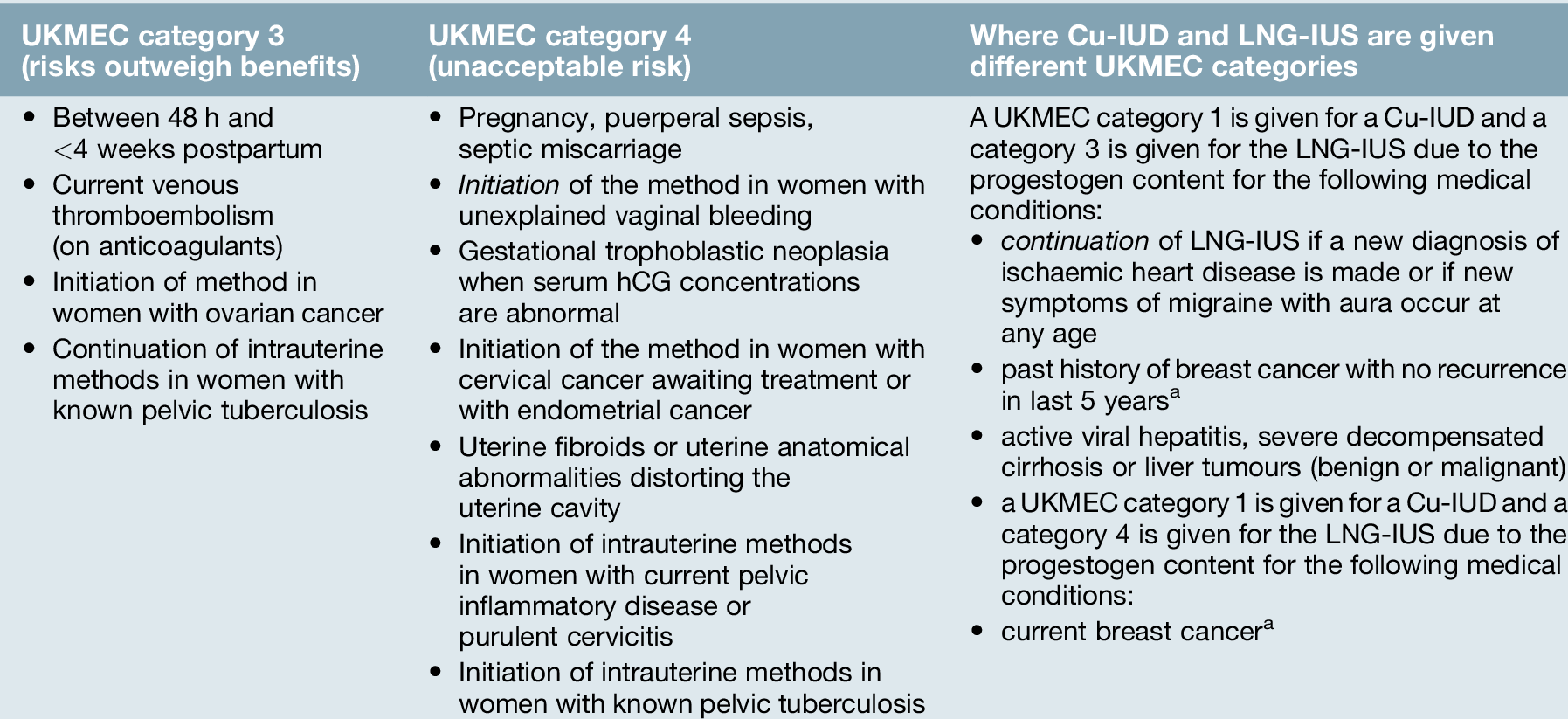

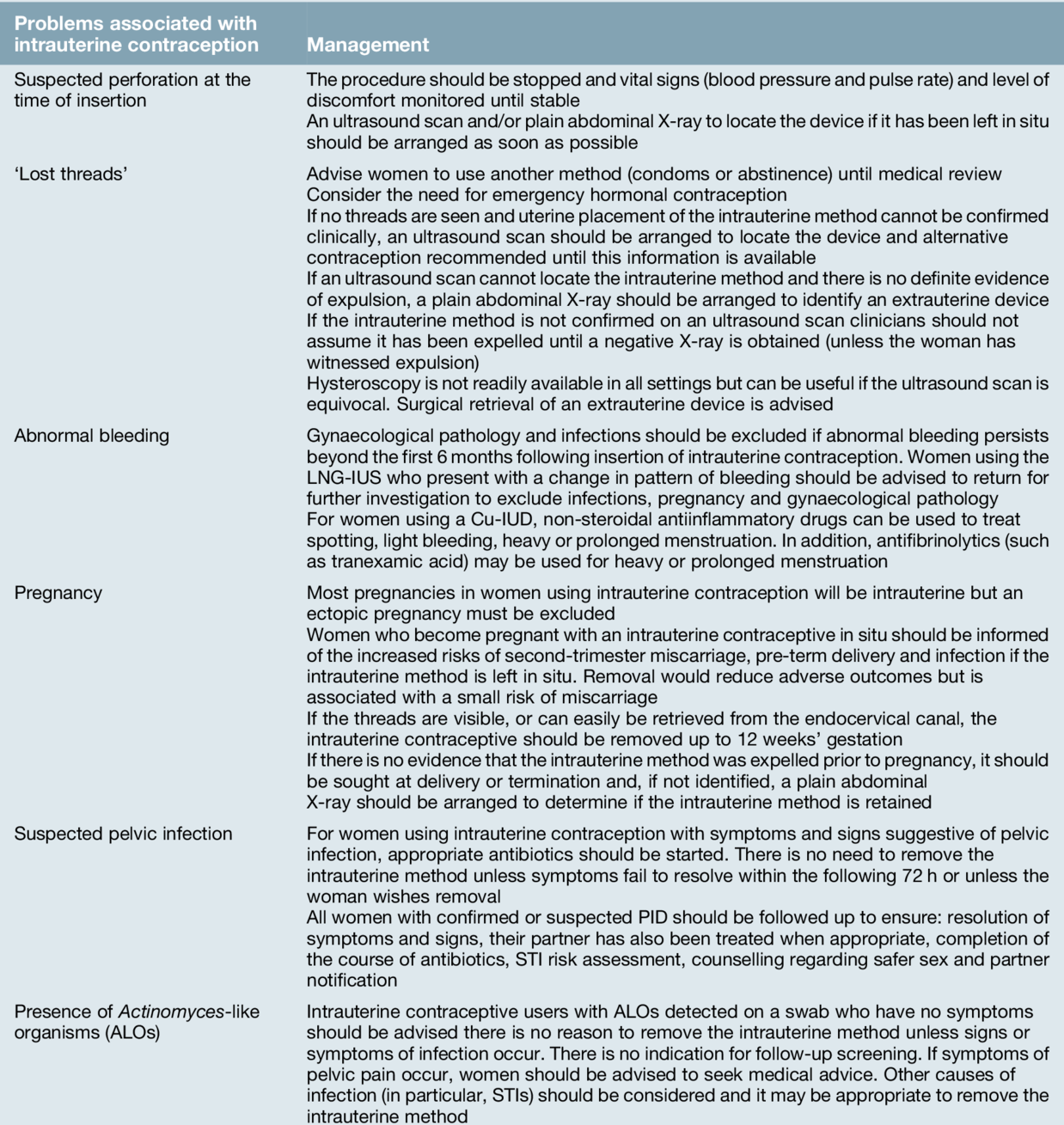

Copper is toxic to ova and sperm and the Cu-IUD works primarily by inhibiting fertilization. In addition, the endometrial inflammatory reaction generated by the Cu-IUD has an anti-implantation effect and alterations in cervical mucus inhibit sperm penetration. Failure rates for intrauterine contraception at 5 years use are low (2% with a 380 mm2 Cu-IUD). Banded Cu-IUDs, which have 380 mm2 of copper in the vertical stem and copper sleeves on the horizontal arms, are the most effective intrauterine devices available and are recommended to be used as a first-line device (Fig. 27.2B). Banded devices available in the UK can be used for up to 10 years. There is no delay in return to fertility after removal of intrauterine contraception. Spotting, light bleeding or heavier or prolonged bleeding is common in the first 3–6 months of Cu-IUD use, but this may settle. There are few contraindications to use of intrauterine contraception (Table 27.4). The management of common problems associated with Cu-IUD use are outlined in Table 27.5.

Insertion

Clinicians who insert intrauterine contraception should be appropriately trained. Discomfort during and/or after insertion of intrauterine contraception and the need for pain relief during insertion should be discussed with women in advance and administered when appropriate. Emergency equipment must be available in all settings where intrauterine contraception is being inserted, and local referral protocols must be in place for women who require further medical input.

Expulsion and perforation

The risk of expulsion with intrauterine contraception is around 1 in 20 but is most common in the first year of use, particularly within 3 months of insertion. The risk of uterine perforation associated with intrauterine contraception is up to 2 per 1000 insertions. Most perforations occur at the time of insertion, but a delayed ‘migration’ is recognized to occur. Immediate perforation may be detected because of acute pain or it may be detected later if pregnancy occurs. Most commonly, perforation is identified following the investigation of ‘missing threads’, although the most common reason for missed threads is that they have curled up and are intrauterine with a normally placed device. The management of suspected perforation and lost threads are outlined in Table 27.5. If the device is not in the uterine cavity, an abdominal X-ray will identify a Cu-IUD (or a LNG-IUS) if it is lying within the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 27.3). Abdominally sited copper IUDs may cause dense adhesion formation and should be removed by laparoscopy or laparotomy.

Pelvic infection

There is an increased risk of pelvic infection in the 20 days following insertion of intrauterine contraception; after this, however, the risk is the same as for the non-IUD-using population. The risk of acquiring pelvic inflammatory disease is related to sexual activity and not the Cu-IUD. A clinical history (including sexual history) should be taken to identify those at higher risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), principally those aged < 25 years or those > 25 years with a new sexual partner or more than one partner in the last year, or if their regular partner has other partners. Women who are at higher risk of STIs or who request STI screening should be tested in advance of insertion of intrauterine contraception. Many laboratories provide dual testing for Chlamydia trachomatis and the Gonococcus via a self-administered low vaginal swab. If results are unavailable before insertion, prophylactic antibiotics should be considered for the higher-risk group (at least to cover C. trachomatis).

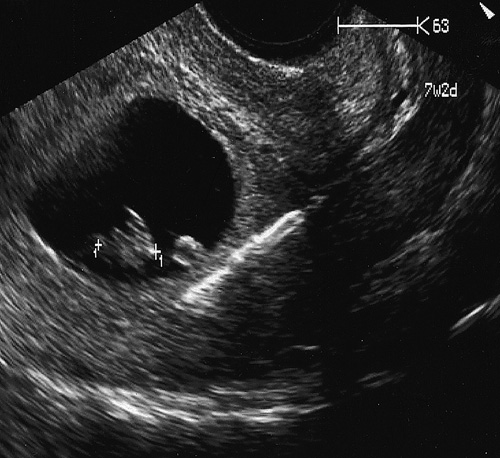

Pregnancy

An IUD-failure pregnancy is rare, but if it occurs, the chance of having an ectopic pregnancy is higher than in those without a device (Table 27.5). The overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is reduced with use of intrauterine contraception when compared to using no contraception, however. No particular device is associated with a lower rate of ectopic pregnancy. If the pregnancy is intrauterine, there is a considerable increase in the risk of spontaneous miscarriage and pre-term labour (Fig. 27.4). Removal of the IUD reduces these risks and should be carried out as soon as is practical, provided the threads are easily seen. If not, no attempt at retrieval should be made (Table 27.5).

Barrier methods

Barrier methods of contraception aim to prevent sperm gaining access to the female upper reproductive tract. An extensive array of barriers has been used (male and female condoms, diaphragms and cervical caps). Barrier methods offer advantages in terms of safety and reversibility, but their efficacy is critically dependent upon consistency and quality of use. The failure rates can be low when they are used correctly by well-motivated couples.

Male and female condoms

Used consistently and correctly, male condoms are up to 98% effective at preventing pregnancy and female condoms are up to 95% effective. Failure rates with ‘real life’ use however, can be much higher and often failures are not recognized at the time. In general, evidence supports the use of condoms to reduce the risk of STI transmission, but, even with correct and consistent use, transmission may occur. Men and women with latex sensitivity or allergy can use polyurethane or deproteinized latex condoms. An advance provision of emergency contraception should be offered to women using condoms as the sole method of contraception. Condom users should be made aware of the risk of pregnancy and STIs should a condom fail.

Male condoms are available in a variety of shapes and colours, with or without spermicide. Condoms lubricated with non-spermicidal lubricant are recommended for use. Additional lubricant should be recommended for use of male condoms for anal sex to reduce the risk of breakage. Non-oil-based lubricants are recommended, as they can be used safely with latex and non-latex condoms. Male condoms must be unrolled over the erect penis before there is any genital contact. Difficulties may occur when air is not excluded from the teat, or when trying to put them on inside out, or if snagging with fingernails occurs, and the condom should be held onto the penis during withdrawal from the vagina to avoid leakage of semen. The standard size available in a particular country may not meet the requirements of all men; a condom that is too large may roll off during intercourse.

The female condom is a polyurethane sheath, its open end attached to a flexible polyurethane ring, which sits at the vaginal entrance, and is available in one size (Fig. 27.5).

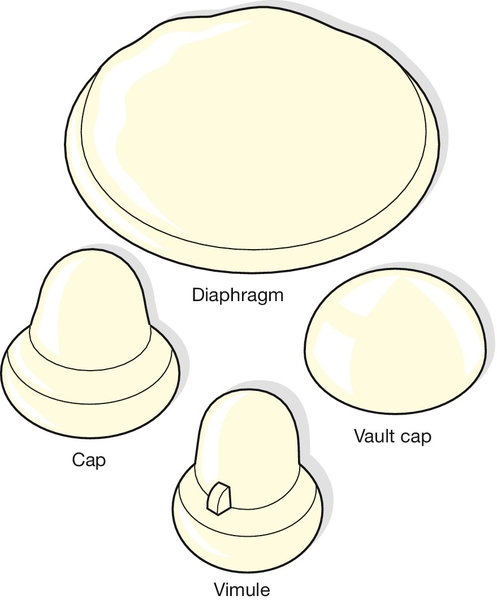

Female diaphragms and caps

These require a relatively high degree of user motivation, and failure rates are comparable with those observed with the male condom. They are divided into two groups: the diaphragm and those that cover only the cervix (caps) (Fig. 27.6). The diaphragm consists of a soft dome, the edge of which contains a supporting metal spring to exert a slight pressure on the vaginal walls. It is inserted to lie diagonally across the vagina between the back of the symphysis pubis and the posterior fornix, but it does not form a complete barrier between the upper and lower vagina. Cervical and vault caps, and the Vimule cap, depend on suction to hold the cap over the cervix or the vaginal vault. When used consistently and correctly and with spermicide, diaphragms and cervical caps are estimated to be between 92% and 96% effective at preventing pregnancy.

There is limited evidence on the use of diaphragms and cervical caps for reducing the risk of STIs. There may be some protection against cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) with diaphragms. Available evidence generally supports the use of female condoms to reduce the risk of STIs, but, even with consistent and correct use, transmission may occur. Women with sensitivity to latex proteins can use a silicone diaphragm or cervical cap, or a polyurethane female condom. The use of a diaphragm or cervical cap by women who have, or are at high risk of HIV infection is not generally recommended. For women with a history of toxic shock syndrome, the use of diaphragms and cervical caps is also not generally recommended. Guidance on the correct use of diaphragms and caps is outlined in Box 27.1. It is usually recommended that diaphragms and caps are used with a spermicide. The use of spermicide alone is not considered to provide effective contraception. Nonoxinol-9 (N-9) is the only spermicide commercially available in the UK. N-9 is a surfactant, which disrupts cell membranes. Epithelial disruption in the vagina and rectum has been identified in association with N-9 use in human and animal models. Repeated and high-dose use of N-9 is associated with an increased risk of genital lesions, which may increase the risk of HIV acquisition, and the WHO recommends that women at high risk of HIV infection should not use N-9. The risks of using a diaphragm or cervical cap (with N-9) in women with a high risk of HIV or those with HIV or AIDS generally outweigh the benefits (UKMEC 3; Table 27.1).

Natural family planning

The Billings method is the most commonly used natural family planning method and should only be taught by an experienced teacher of the technique (see History box). This method requires the restriction of intercourse to those days of the menstrual cycle on which conception is least likely to occur.

Women assess cervical mucus changes throughout the cycle. Prior to ovulation (the fertile period) cervical mucus is clear, watery (i.e. of low viscosity) and is easily stretched into strands (‘spinnbarkeit’). After ovulation (the non-fertile period), mucus is thick and sticky. This knowledge can be used to identify days where intercourse can occur with reduced likelihood of conception.

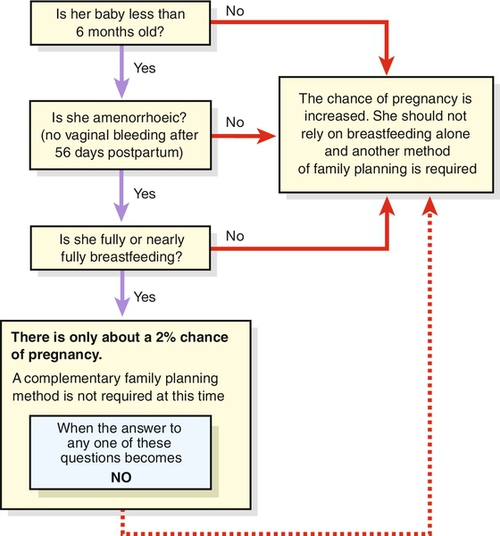

The lactational amenorrhoea method (LAM) provides a very effective technique (98%) if the woman is: fully breastfeeding (day and night on demand) with no supplementary feeds, she is less than 6 months postpartum and she is amenorrhoeic. Another method of contraception should be introduced if periods return (bleeding before 56 days after delivery is not considered in this context) with the introduction of weaning, or after 6 months (Fig. 27.7).

Emergency contraception

Emergency contraception (EC) can be used:

![]() after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI)

after unprotected sexual intercourse (UPSI)

![]() after ‘accidents’ with a barrier method (e.g. burst condom or diaphragm removed too early)

after ‘accidents’ with a barrier method (e.g. burst condom or diaphragm removed too early)

![]() if pills are missed, injectable methods are late or an intrauterine method is expelled.

if pills are missed, injectable methods are late or an intrauterine method is expelled.

It can be difficult to accurately assess an individual woman’s risk of pregnancy. A woman who has a single act of UPSI mid-cycle has approximately a 20–30% risk of pregnancy. This pregnancy risk will vary depending on the time of the cycle. The risk reduces to 2–3% before day 10 and after day 17, in a regular 28-day cycle. Other factors have an effect on pregnancy risk, such as the age of the woman. Three methods are currently available: progestogen-only emergency contraception (POEC), ulipristal acetate (UPA) and the Cu-IUD. The most effective emergency method of contraception is the Cu-IUD and all women should be offered this option. However, women may decline this option for the less invasive oral methods POEC and UPA.

Progestogen-only emergency contraception (POEC)

The progestogen-only (levonorgestrel) method is effective up until 72 h after UPSI. The pills (1.5 mg LNG) inhibit or delay ovulation and prevent up to 84% of expected pregnancies. For women using liver-enzyme-inducing drugs, a single 3 mg POEC may be considered between 73 and 120 h after UPSI but women should be informed of the limited evidence of efficacy, that such use is outside product licence and the alternative of a Cu-IUD. Women who experience vomiting within 2 h of administration of POEC will require repeat dose or may consider a Cu-IUD. POEC does not provide contraception for the remainder of the cycle and effective contraception or abstinence is advised. Women should be advised to undergo a pregnancy test if their period is more than 7 days late or lighter than usual.

Current advice is to initiate the chosen future method of contraception at or around the time of POEC use to reduce the future risk of pregnancy from further UPSI. This is the so-called ‘quick start’ method advocated by the FSRH. It will take a further 7 days (or 2 days in the case of POP) before contraceptive protection is achieved. A pregnancy test is recommended at least 3–4 weeks after ‘quick start’ contraception. There is no good evidence that initiating a hormonal method of contraception (including DMPA) is associated with increased risk of teratogenicity should EC fail.

Ulipristal acetate (UPA)

The progesterone receptor modulator ulipristal acetate was introduced to the UK in 2009 (ellaOne®). A 30-mg dose of UPA is licensed to be used up to 5 days (120 h) after UPSI. The primary mode of action of UPA is to inhibit or delay ovulation. There is some effect of UPA on the endometrium but it is unclear if this will inhibit implantation. UPA is at least as effective as POEC and prevents around 85% of expected pregnancies. Use of UPA can cause delay in the onset of menstruation and menstrual irregularities similar to POEC. For women using a liver enzyme-inducing drug, UPA is not recommended. Use of UPA is not recommended for women with severe asthma or severe hepatic impairment. UPA is excreted in breast milk for up to 36 h and breast milk should be discarded during this time. The efficacy of UPA may be reduced by use of antacids, proton pump inhibitors and H2 receptor antagonists. Following UPA administration, ‘quick start’ can be used to initiate the woman’s future contraception. The current advice is that if commencing CHC, subdermal implant or injectable contraception, condoms are advised for 7 days (as usual) plus a further 7 days before contraceptive protection is provided. For POP ‘quick start’ after UPA condoms are recommended for a total of 9 days (the usual 2 days plus 7 days to allow effect of UPA on progesterone receptors to reverse).

The Cu-IUD

A Cu-IUD can be inserted up to 5 days after the first episode of UPSI or up to 5 days after the predicted date of ovulation (which may be more than 5 days after intercourse). Almost 99% of expected pregnancies can be prevented. It is for this reason that women of any age may opt for this method of emergency contraception. The copper is immediately toxic to ovum and sperm, thus making it effective immediately after insertion. Women who attend following UPSI more than 5 days previously can be offered a Cu-IUD, which can be inserted if she is within 5 days of her expected date of ovulation (that is up to day 19 in a woman with a regular 28-day cycle), at which time a pregnancy will not yet exist. The LNG-IUS is not effective as emergency contraception and should not be used for this indication.

Sterilization

Female sterilization

Counselling and advice on sterilization procedures should be provided to women and men within the context of a service, providing a full range of information and access to other methods of contraception. This should include information on the advantages and disadvantages and relative failures. Other female methods of contraception such as subdermal implants have lower failure rates compared with female sterilization, and intrauterine methods have similar failure rates. Vasectomy carries a lower failure rate and there is less risk related to that procedure. All women must be informed of the risks of laparoscopy, including those of visceral and vascular injury necessitating additional surgery. Laparoscopic sterilization is usually carried out using a technique called tubal occlusion (blocking of the fallopian tubes) most often achieved with a titanium clip, under general anaesthesia.

A more recently developed method of hysteroscopic female sterilization is also available in many centres throughout the UK. This involves tubal cannulation and occlusion of the fallopian tubes from within the uterine cavity. The procedure is designed to be performed under local anaesthetic.

Failures can occur with all methods of sterilization and a pregnancy can occur several years after the procedure. The lifetime risk of failure is estimated to be 1 in 200 for laparoscopic sterilization. The overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is not increased after sterilization compared with women using no method of contraception; however, women should be informed that, if pregnancy occurs, the resulting pregnancy may be ectopic (because tubal anatomy is distorted).

Laparoscopic sterilization is intended to be permanent, however it may be reversed but has variable success rates and women should be informed of this. Hysteroscopic sterilization is not reversible owing to scarring in the fallopian tubes.

Female sterilization is not associated with an increased risk of heavier or longer periods when performed after 30 years of age. There is an association with a subsequent increased hysterectomy rate, although there is no evidence that tubal occlusion leads to problems that require hysterectomy.

Sterilization involving ligation of the fallopian tubes can be performed at the time of caesarean section if there has been appropriate pre-procedure counselling.

Vasectomy

Vasectomy is the ligation of the vasa deferentia for the purpose of excluding spermatozoa from the ejaculate. The procedure is usually performed under local anaesthesia. Vasectomy is intended to be permanent but men should be given information on the success rates associated with reversal. Following vasectomy, an effective contraceptive must be used until azoospermia has been confirmed by semen analysis. It can take up to 20 ejaculations to clear any sperm ahead of the now blocked vas deferens.

There is no increase in risk of testicular cancer or heart disease associated with vasectomy. The association, in some reports, of an increased risk of being diagnosed with prostate cancer is currently considered not to be causal. Men should be informed about the possibility of chronic testicular pain after vasectomy. Serum testosterone concentrations, libido and the colour, consistency and volume of the ejaculate are unaltered following vasectomy. Vasectomy is highly reliable with a failure rate of 1 in 2000.