37 Constipation

• Constipation has a variety of meanings to patients. Ask about pain, stool frequency, stool hardness, and difficulty with passage.

• Dangerous conditions such as early bowel obstruction can mimic functional constipation, especially in the elderly. Red flags include severe pain, vomiting, fever, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute onset without an obvious cause (e.g., opiate use), peritoneal signs, and significant systemic symptoms.

• In most patients, constipation has a functional, nonemergency cause that is often related to medications or lifestyle habits such as dietary fiber intake, fluid intake, and toileting.

• The treatment goal for uncomplicated constipation consists of initial cleansing, a maintenance plan, and preventive lifestyle changes.

• A wide range of underlying conditions, such as malignancy and systemic disorders, can cause constipation. Primary care follow-up is warranted.

Perspective

Epidemiology

Constipation is common at all ages, with the reported prevalence ranging from 2% to 27%,1 depending on the definition used. Prevalence is higher in women than in men (approximately 2 : 1), perhaps related to an increased prevalence of pelvic floor dyssynergy in women.2 Prevalence is higher in the elderly: in those older than 84 years, self-reported rates are 25.7% in men and 34.1% in women,3 and up to 74% of elderly nursing home residents are taking laxatives daily.2 The condition is much less common in populations with non-Western diets containing more bulk. Although many people do not seek medical attention for their constipation, this condition is estimated to result in almost $7 billion in medical costs in the United States each year.3

Pathophysiology

Constipation is often multifactorial, with disordered movement of stool through the colon and anorectum. Oral intake, hydration, and general mobility affect colonic function. Numerous anatomic and structural entities, gastrointestinal (GI) disorders, medications, and systemic disorders may secondarily lead to constipation (Boxes 37.1 to 37.4) by altering intraluminal contents, fluid balance, intestinal contractions, or neuromuscular coordination. However, the majority of patients have primary chronic functional constipation that falls into one or more of three categories. Many actually have normal intestinal transit time; their constipation is perceptual and related to habits. Others have slow transit times because of overall colonic slowing (pancolonic inertia) or sigmoid spasm (left colonic hypermotility with uncoordinated segmental contractions and poor propulsion). An important but underrecognized group has pelvic floor dyssynergy (obstructive defecation), an acquired behavioral condition that begins with chronically ignoring the urge to defecate. Disordered defecatory function of the pelvic floor muscles and sphincters eventually produces difficulty expelling stool, even if soft. Hormonal contributions are unclear, but constipation is common in pregnancy4 and before menstruation. Contrary to past thinking, chronic laxative abuse does not cause chronic constipation.5 High rates in the elderly are not due to aging itself but to concomitant conditions or medications.6

Box 37.2 Systemic Causes of Constipation

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

A formal consensus definition is therefore used by gastroenterologists, and the label of chronic functional constipation requires two or more of the following occurring for at least 3 months of the past year: straining for at least 25% of defecations, lumpy or hard stools in 25% or more of defecations, sensation of incomplete evacuation in 25% or more of defecations, sensation of anorectal obstruction or blockage in 25% or more of defecations, manual maneuvers to facilitate passage (digital evacuation or support of the pelvic floor) in 25% or more of defecations, or fewer than three defecations per week.7 A practical pediatric definition is delay or difficulty in defecation present for 2 or more weeks.8

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Constipation is a symptom that may be secondary to a myriad of other causes, but it most often represents chronic functional constipation. Boxes 37.1 to 37.4 list the various causes of secondary constipation—GI and systemic disorders, medications, and additional causes in children.

Red flags for a more serious acute condition include severe pain, vomiting, fever, GI bleeding, acute onset, persistent tachycardia, hypotension, and peritoneal signs. Elderly patients warrant higher clinical suspicion for worrisome causes, particularly if febrile, and extraabdominal infections may be manifested as general failure to thrive or constipation. In adults older than 50 years, anemia, weight loss, acute change in bowel habits, GI bleeding, and a family history of colon cancer or inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS) are “alarm” findings of possible underlying malignancy or IBS and warrant early referral for endoscopy or radiographic studies.9

Considerations by Patient Age

Adolescents

Constipation is more common in adolescent girls than boys, with the predominant symptom being straining to initiate defecation. Typically, this is a functional problem arising from chronic suppression of the urge to defecate for psychosocial reasons. An underlying eating disorder or surreptitious opiate use should also be considered.10

Elderly Institutionalized Patients

Mental confusion, immobility, poor oral intake, limited toileting opportunities, and medications all contribute to a high prevalence of chronic constipation and high risk for fecal impaction. Impaction is the most common cause of fecal incontinence and may lead to stercoraceous ulceration or perforation of the colon.11

Considerations by Cause

Functional Constipation

In the vast majority of patients, constipation has an idiopathic functional cause related to psychosocial stressors, unintentionally learned rectal dysfunction, and lifestyle habits such as dietary fiber intake, fluid intake, and toileting. About 25% of patients have a component of pelvic dyssynergy. IBS is a common functional dysmotility disorder characterized by intermittent abdominal pain, distention, and variable diarrhea or constipation with no structural lesions found; concomitant upper GI symptoms and pelvic dyssynergy are common.12,13

Treatment

Patients with pseudoobstruction warrant inpatient care unless they are known to have chronic intermittent pseudoobstruction with only a mild exacerbation of their constipation. For acute megacolon from colonic pseudoobstruction, the prokinetic neostigmine is a standard therapy, but this is usually ordered by the gastroenterologist and followed by decompressive colonoscopy.14 Prokinetic agents are contraindicated in patients with obstruction, perforation, or peritonitis.

The plan for bowel care includes:

• Initial cleansing (usually laxatives, both oral and rectal)

• Maintenance plan (increase fluid and fiber intake, consideration of laxatives or softeners)

• Behavioral modification (diet, toilet habits, exercise)

• Other interventions tailored to the suspected underlying cause or causes

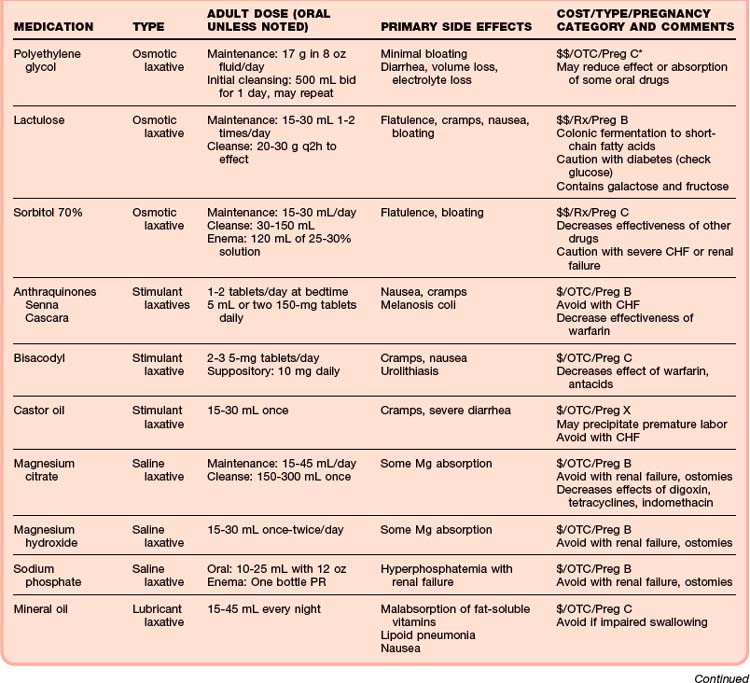

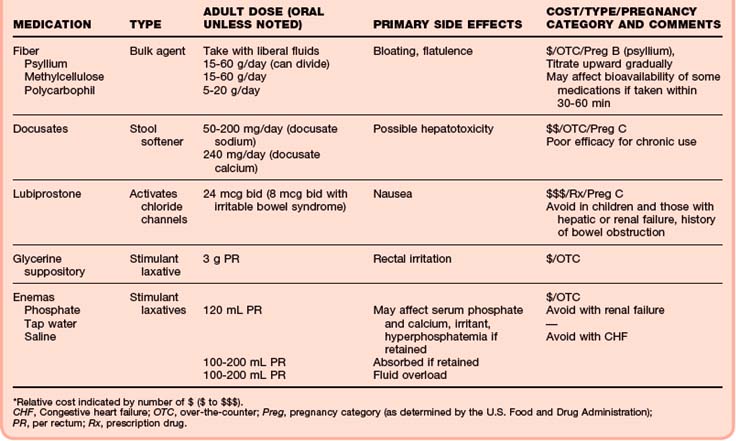

Most patients are sent home with a management plan and education, but initial cleansing in the ED or observation unit and serial reexamination should be considered if a suspicion remains about a more serious underlying cause or if the patient may not be able to perform the initial steps (or has no reliable caretaker to do so). A myriad of products are available for constipation (Table 37.1).15 Selection should focus on efficacy, safety, and cost, as well as patient preference.

see Table 37.1 Therapeutic Agents for Constipation in Adults, online at www.expertconsult.com

If ED cleansing is necessary, time constraints prompt the use of stimulant laxatives per rectum, either suppositories (glycerin or bisacodyl) or enemas (tap water or phosphate). A topical anesthetic gel will decrease defecatory pain. Digital disimpaction may speed the process but is generally reserved as a last resort. Digital stimulation (several gentle rotations of a gloved, well-lubricated finger within the rectum) may loosen up fecal concretions and stimulate spontaneous defecation; this may be repeated after a 10-minute pause. If no response is seen, the lumps will need to be gently broken up and removed by finger. In spinal cord or elderly patients, the pulse and blood pressure should be monitored during disimpaction for changes secondary to vagal stimulation or autonomic dysreflexia.16

Outpatient treatment should start with osmotic laxatives such as PEG to be taken at home or just bulk agents, prune juice, or dried prunes if the constipation is mild. A stimulant laxative (e.g., glycerin suppository) is to be taken if the simpler treatment fails.17 Strong evidence supports the use of PEG, moderate evidence supports lactulose and psyllium, and little evidence exists for or against other agents.18,19 In the elderly, all laxative categories may cause some bloating, flatulence, or abdominal pain.20

Osmotic laxatives are hyperosmotic agents that generally provide excellent relief of constipation and may be used in small doses for the long term if needed. A large volume of PEG is used for procedural preparation or initial cleansing of large fecal loads, but most cases of constipation respond to one packet (17 g) daily, which may be continued as a maintenance dosage; PEG without electrolytes is more palatable. Lactulose and sorbitol (given orally or as enemas) are nonabsorbable sugars degraded by colonic bacteria to acids that increase stool acidity and osmolarity and thereby lead to accumulation of fluid in the colon to speed defecation. Lactulose is excellent for long-term use in small doses but should be avoided in most diabetics. Corn syrup is used in infants.8

• Higher intake of fluids (≥2 L daily) and fiber

Concomitant treatment of underlying causes and contributors is essential. Treatment of painful rectal problems improves overall bowel function. Although they are not generally prescribed in an ED setting, other treatments are available.19 Lubiprostone is a bicyclic fatty acid that activates GI chloride channels to increase intestinal fluid secretion and effectively treats chronic functional constipation.21 Even in the elderly, pelvic floor dyssynergy may respond well to physical therapy, behavioral modification, and biofeedback training.22,23 Surgery may relieve specific defects, such as rectoceles, and is the mainstay for treatment of Hirschsprung disease.9

Follow-Up Care and Patient Education

Patient Education

Patient education is crucial. Patients are often frightened and disturbed by symptoms that the physician may take lightly; reassurance and discussion are invaluable. As appropriate, the EP should explain that cancer or other serious disease is highly unlikely but that compliance with follow-up remains essential. The patient should be taught about “normal” bowel function, general measures to improve symptoms, and reasonable goals. The EP and nurse must also ensure that patients know how to use the items recommended, especially suppositories or enemas.24

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Functional Constipation

General Concepts

Goals: bowel movements three or more times per week, pain free, with minimal straining.

Daily bowel movements are not needed.

The long-term prognosis is excellent and serious diseases such as cancer are not likely, but outpatient follow-up is always important to see how you are doing and whether other tests may be needed.

If constipation is long-standing, return to “normal” bowel habits may take several weeks.

Keep a bowel diary (brief description of food and fluid intake, bowel movements, problems) for 1 to 2 weeks to review with your primary care doctor.

Recommended Medications and Laxatives

Follow the plan recommended by your physician today.

Short-term use of strong laxatives for the next few days is OK for initial cleansing, but avoid long-term use unless your primary care doctor advises you to do so.

Small daily doses of osmotic laxatives such as lactulose or polyethylene glycol may be needed for a few weeks, along with bowel retraining.

Healthy Bowel Habits

Visit the toilet every day after the meal of your choice (breakfast is best), and sit for 15 to 20 minutes:

Drink at least 2 L of fluids (without caffeine or alcohol) daily to stay well hydrated.

Gradually increase your fiber intake (bran, high-fiber cereals, fruits, vegetables, or nonprescription fiber products such as psyllium) to about 25 g/day.

Note whether milk or milk products aggravate your symptoms.

Regular exercise (walking) may help stimulate improved bowel movements.

Bouras EP, Tangalos EG. Chronic constipation in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:463–480.

Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5–21.

Constipation Guideline Committee of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children: recommendations from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(3):e1–13.

Rao SS. Dyssynergic defecation and biofeedback therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:569–586.

Youssef NN, Sanders L, Di Lorenzo C. Adolescent constipation: evaluation and management. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15:37–52.

1 Lembo AJ, Camilleri M. Chronic constipation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1360–1368.

2 Brandt LJ, Prather CM, Quigley EM, et al. Systematic review on the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(Suppl 1):S5–21.

3 Crane SJ. Chronic gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:721–734.

4 Wald A. Constipation, diarrhea, and symptomatic hemorrhoids during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:309.

5 Wald A. Is chronic use of stimulant laxatives harmful to the colon? J Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;36:386–389.

6 World Gastroenterology Organization. Practice guidelines: constipation. Available at guidelines@worldgastroenterology.org, 2007.

7 Lembo AJ, Ullman SP. Constipation. 9th ed. Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, eds. Sleisinger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2010;vol 1:259–279.

8 Constipation Guideline Committee of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. Evaluation and treatment of constipation in infants and children: recommendations from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006;43(3):e1–13.

9 Ternent CA, Bastawrous AL, Morin NA, et al. Practice parameters for the evaluation and management of constipation. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:2013.

10 Youssef NN, Sanders L, Di Lorenzo C. Adolescent constipation: evaluation and management. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15:37–52.

11 Creason N, Sparks D. Fecal impaction: a review. Nurs Diagn. 2000;11:15–21.

12 Laine C, Goldmann D, Wilson JF. In the clinic: irritable bowel syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:ITC7-1–ITC-16.

13 Schoenfeld P. Efficacy of current drug therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: what works and does not work. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:319–335.

14 Batke M, Cappell MS. Adynamic ileus and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92:649–670.

15 Singh S, Rao SS. Pharmacologic management of chronic constipation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010;39:509–527.

16 Kyle G, Prunn P, Oliver H. A procedure for the digital removal of faeces. Nurs Stand. 2005;19:33–39.

17 Rao SS. Constipation: evaluation and treatment. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2003;32:659–683.

18 Ramkumar D, Rao SS. Efficacy and safety of traditional medical therapies for chronic constipation: systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:936–971.

19 American College of Gastroenterology Constipation Task Force. An evidence-based approach to the management of chronic constipation in North America. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:4.

20 Zarowitz BJ. Pharmacologic consideration of commonly used gastrointestinal drugs in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:447–562.

21 Johansen JF, Ueno R. Lubiprostone, a locally acting chloride channel activator, in adult patients with chronic constipation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;25:1351–1361.

22 Rao SS. Dyssynergic defecation and biofeedback therapy. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2008;37:569–586.

23 Bouras EP, Tangalos EG. Chronic constipation in the elderly. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2009;38:463.

24 MD Consult. Patient education: laxatives, OTC products for constipation (2008); constipation (2008); constipation, management of (2011). Mdconsult.com.