11.2 Connective tissue and the pudendal nerve in chronic pelvic pain

Connective tissue dysfunction in chronic pelvic pain

Mechanisms of development of subcutaneous panniculosis

Superficial to muscles with myofascial trigger points

Dermatomes of inflamed neural structures

Superficial to areas of joint dysfunction

Connective tissue restrictions and altered neural dynamics

Efficacy of connective tissue mobilization

Connective tissue manipulation

The pudendal nerve in chronic pelvic pain

Connective tissue dysfunction in chronic pelvic pain

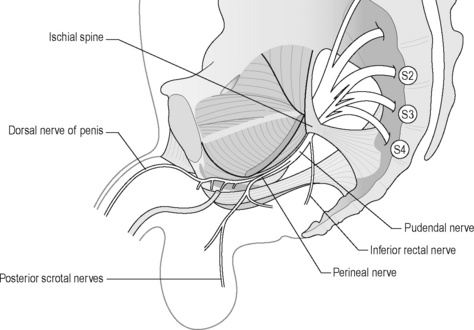

Several different terms have been used to describe connective tissue restrictions and/or dysfunction. According to orthopaedic physician Robert Maigne, cellulagia is ‘defined as neurotrophic manifestations that include subcutaneous tenderness and thickening’. It can be detected by using the ‘pinch-roll’ test, in which a fold of skin is rolled between the fingers causing pain, with the clinician noting thickening (Maigne 1995) (Figure 11.2.1).

Figure 11.2.1 • Skin rolling test: the skin of the perineum is pinched just below the level of the anus and rolled to the front searching for a sharp pain at one level (Beco 2004)

Physical therapist Maria Ebner (1985) used the term trophic oedema to describe thickened hypersensitive loose connective tissue. Other literature sources have referred to dermographia, which is defined as a condition in which pressure or friction of the skin gives rise to a transient reddish mark so that a line on the skin becomes visible (Merck Manual 2008). Finally, the terms panniculosis and fibrositis have also been used to describe dysfunctional connective tissue (Travell & Simons 1993), defined as inflammatory hyperplasia of the white fibrous tissue. This text will use the term subcutaneous panniculosis to describe thickened connective tissue that is tender upon pinch rolling (i.e. dysfunctional connective tissue).

In addition to presenting as thickened or dense upon skin rolling, areas of subcutaneous panniculosis may show vasomotor, pilomotor and sudomotor reactions, increased subcutaneous fluid and atrophy or hypertrophy of the underlying muscles (Chaitow 2010). Underlying muscle atrophy is the resultant effect of the thickened tissue interfering with proper functioning of sodium–potassium pumping mechanisms in muscles (Ebner 1975). Panniculosis can cause local nociceptive pain via the peripheral nervous system, and it is hypothesized to cause referred pain in distant locations including the viscera through the central nervous system (Bischof & Elmiger 1963).

Mechanisms of development of subcutaneous panniculosis

When connective tissue becomes dysfunctional the problems that arise are in proportion to the support the tissues provide when they are healthy. Several mechanisms have been identified to explain how dysfunction develops in the subcutaneous tissue. These are as the result of visceral referred pain, in tissue superficial to myofascial trigger points, in the cutaneous distribution of inflamed peripheral nerves, and superficial to or referred from areas of joint dysfunction (Ebner 1975, Travell & Simons 1993, Beco 2004, Maigne 1996).

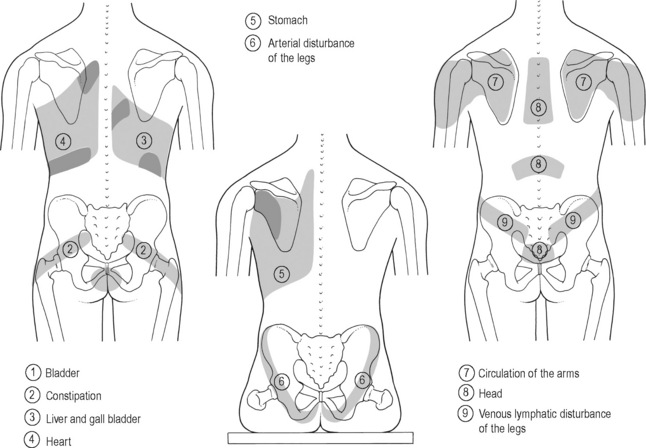

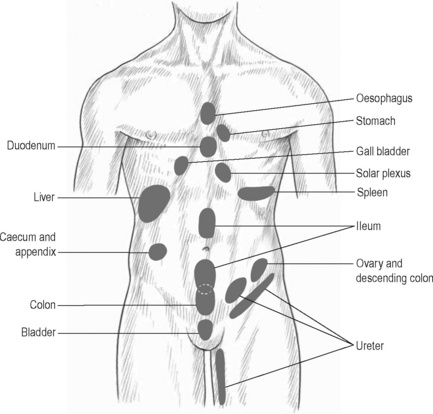

Viscerosomatic reflex

The viscerosomatic reflex is a reflex in which somatic manifestations occur in response to visceral disturbances. More specifically, the visceral-cutaneous reflex is a phenomenon where disturbances or disease in visceral organs refer pain along the distribution of somatic nerves which share the same spinal segment as the sensory sympathetic fibres to the organ affected (Head 1893). The visceral-cutaneous reflexes have been studied by many and are commonly referred to as Head’s zones, Chapman’s reflexes, or Mackenzie’s zones (Beal 1985) (see Figures 11.2.2, 11.2.3). The reflex is initiated by afferent impulses from visceral receptors, impulses travel to the dorsal horn of the spinal cord, synapse with interconnecting neurons, connect with sympathetic and peripheral motor efferents resulting in sensory changes in the blood vessels and skin (and also muscle and viscera) (Bischof & Elminger 1963). If the pathological visceral afferent stimulation becomes chronic, neurogenic plasma extravasation will occur in the skin, thereby causing vasoconstriction in the periphery, hyperaesthesia and thixotropic changes. In more recent literature, three plausible neural mechanisms have been identified in animal models to explain visceral-cutaneous reflexes.

Figure 11.2.2 • Head’s zones.

Adapted from Chaitow (2003) Modern Neuromuscular Techniques, second ed, Elsevier.

Figure 11.2.3 • McKenzie’s zones.

Adapted from Chaitow (2003) Modern Neuromuscular Techniques, second ed, Elsevier.

In 1996 Takahashi & Nakajima published that plasma extravasation occurred as a result of antidromic stimulation of C-fibres in spinal nerves. It is noted that with unilateral stimulation changes in the skin can occur unilaterally or bilaterally (Takahashi & Nakajima 1996).

Studies suggest that the actual mechanism may be a combination of the three described processes, as noted by Ursula Wesslemann et al. in 1997. One potential mechanism is described because dichotomizing sensory neurons have a branch to both the uterus and to the skin. Uterine inflammation could cause excitation of the visceral branch of the afferent neuron, leading to antidromic activation of the somatic branch causing neurogenic plasma extravasation. Wesselmann also hypothesized that visceral afferent neurons may excite cutaneous afferent neurons. The result of this spinal mechanism is antidromic activation of cutaneous afferent fibres, again resulting in plasma extravasation. Finally, the paper discussed the possibility that sympathetic post-ganglionic nerve terminals must be intact. This was demonstrated by a decrease in plasma extravasation when the anterior spinal root was not intact (Wesslemann & Lai 1993).

Similarly, basic science studies (Beal 1985, Craggs 2005) have shown that somatic disturbances cause visceral changes, otherwise known as the somatovisceral reflex.

Superficial to muscles with myofascial trigger points

Travell & Simons (1993) have reported a strong association between active myofascial trigger points and subcutaneous connective tissue restrictions. Dermographia/fibrositis commonly occurs most often over muscles of the back of the neck, shoulders and torso, and less frequently over limb muscles. In panniculosis, the subcutaneous tissue exhibits increased viscosity suggestive of thixotropy. It is proposed by Travell and Simons that the connective tissue restrictions may be related to sympathetic nervous system activity involving mechanisms operating in the underlying myofascial trigger points. Treating the panniculosis can relieve myofascial trigger point activity and/or make the underlying myofascial trigger point more responsive to treatment. Travell and Simons identify the need for a well-designed study to critically evaluate the relationship between myofascial trigger point activity and the presence of overlying panniculosis.

Dermatomes of inflamed neural structures

The ‘pinch-roll’ test (of the subcutaneous tissue in the territory of a peripheral nerve) is commonly accepted as a clinical indicator of inflamed neural tissue. Referred pain is accompanied by hyperalgesia of the skin and subcutaneous tissues in the involved dermatomes. This hyperalgesia or hypersensitivity can be revealed by gently grasping a fold of skin between the thumbs and forefingers, lifting it away from the trunk and rolling the subcutaneous surfaces against one another in a pinch and roll fashion. The entire dermatome may be affected or only partial tissue changes may be seen (Maigne 1996, Beco 2004).

Superficial to areas of joint dysfunction

Robert Maigne (1995, 1996) coined the term ‘cellulagia’ when reporting that intervertebral joint dysfunction causes neurotrophic reflexes. This cellulagia can occur in the skin innervated by the corresponding nerve roots and in tissue superficial to areas of vertebral dysfunction.

The dysfunctional tissue itself and the sequellae associated with subcutaneous panniculosis can perpetuate chronic pelvic pain (CPP) and dysfunction. Subcutaneous panniculosis can cause local nociceptive pain, hypothesized visceral referred pain through the central nervous system, underlying muscle dysfunction and altered neurodynamics. The thickening of the skin causes ischaemia and therefore nociceptive pain via the peripheral nervous system (Holey 1995). In addition to local pain, the presence of increased subcutaneous fluid will cause an alteration in the osmotic pressure in cells. There is retention of sodium and associated excretion of potassium, resulting in water retention that interferes with the neuromuscular conducting mechanism (Ebner 1975). The physiological consequence of this is underlying muscle atrophy, which may then lead to the development of myofascial trigger points, a further source of pain and dysfunction. Multiple literature sources describe the mechanisms of which subcutaneous panniculosis can perpetuate visceral disturbance and that the association between cutaneous dysfunction and visceral disturbance is so high that examination of the skin can be used as a predictor of potentially undiagnosed visceral disease (Korr 1949, Wilson 1956, Grainger 1958, Beal 1985, Tillman & Cummings 1992).

Connective tissue restrictions and altered neural dynamics

As discussed below, a peripheral nerve is vulnerable to neural dynamics if its blood supply and/or normal neurobiomechanics are compromised along its path. Ischaemia or thickness associated with subcutaneous panniculosis can compromise neural gliding mechanisms, particularly when the peripheral nerves innervate or transect the dysfunctional tissue region (Butler 2004).

Any muscle and/or tissue and/or structure innervated by an affected nerve may begin to generate pain (Butler 2004). For example, a patient with connective tissue restrictions in the territory of the pudendal nerve may experience sharp, stabbing vaginal or urethral pain with increasing degrees of hip flexion. This is because the nerve must lengthen when the hip flexes; if the tissue is restricted the nerve will not be able to lengthen and the adverse tension results in neuralgic pain in the territory of the nerve. Consequently, because the and/or perineal portions of the pudendal nerve innervate the distal third of the urethra a patient may subsequently feel urethral burning. In terms of bowel function, it is not uncommon for patients with CPP to experience constipation. Connective tissue restrictions affecting the pudendal nerve can also cause neuralgia symptoms, as the restrictions will restrict the neural mobility required for lengthening when a person strains. As a result, a patient may feel neuralgic symptoms in the territory of the nerve, either immediately or with a delayed onset (Holey 1995).

The matrix of areolar connective tissue also serves to deposit collagen for the formation of scar tissue. Commonly, women with CPP have undergone laparoscopic investigation as an attempt to identify pain generators. The trochar (a surgical instrument) may have been used through the umbilicus, in the suprapubic region, or other lower abdominal sites. Formation of scar tissue here can directly create restriction of the ilioinguinal, iliohypogastric and genitofemoral nerves (Howard 2000). Peri-umbilical and suprapubic subcutaneous panniculosis secondary to incisions have been associated with urinary urgency, frequency and dysuria (Fitzgerald & Kotarinos 2003).

Efficacy of connective tissue mobilization

Over the last 20 years basic science research has confirmed the interaction between muscle, skin, viscera and central and peripheral nervous systems supporting the importance of addressing connective tissue as part of any pain-related treatment programme. Recent clinical research shows the physiological and clinical benefits of CTM (Kaada & Torsteinbo 1989, Brattbert 1999, Maddali-Bongi et al. 2009, Fitzgerald et al. 2009).

The Urological Pelvic Pain Collaborative Research Network and the National Institutes of Health examined the feasibility of conducting a randomized clinical trial to compare two methods of manual therapy, external and internal myofascial physical therapy (MPT), compared to traditional external global therapeutic massage (GTM) among patients with urologic CPP syndromes (Fitzgerald et al. 2009). Connective tissue manipulation was the primary external myofascial technique in the MPT group. They were able to standardize both treatment approaches. They found the MPT group had a response rate of 57% which was significantly higher than the rate of 21% in the GTM treatment group (P = 0.03). The overall response rate of 57% in the MPT group suggests that MPT represents a clinically meaningful treatment option. We can infer from these results that there is clear evidence of benefit of connective tissue manipulation in patients with myofascial pelvic pain and dysfunction.

One recent study evaluated the efficacy of a rehabilitation programme based on the combination of connective tissue massage and McMennell joint manipulation specifically for the hands of patients suffering from systemic sclerosis (Maddali-Bongi et al. 2009). In the 40 patients enrolled, 20 (interventional group) were treated for a 9-week period with a combination of connective tissue massage, McMennell joint manipulation and a home exercise programme, and 20 (controlled) were assigned only to a home exercise programme. The interventional group improved in multiple functional and quality of life tests at the end of the treatment (P < 0.0001) versus the control group. Therefore, they concluded that the combined treatment may lead to an improvement in hand function and quality of life.

In 1999 Brattberg investigated the effect of connective tissue massage in the treatment of patients with fibromyalgia. He randomized 48 individuals diagnosed with fibromyalgia, 23 in the treatment group and 25 in the reference group. After a series of 15 treatments of CTM he found that the treatment group reported a pain-relieving effect of 37%, reduced depression and the use of analgesics, and positive effects in their quality of life (Brattbert 1999).

In 1989, another study examined the concentration of plasma beta-endorphins in 12 volunteers before and 5, 30 and 90 minutes after a 30-minute session of CTM. They found a moderate mean increase of 16% in beta-endorphin levels from 20.0 to 23.2 pg/0.1 ml (P = 0.025) lasting for approximately 1 hour with a maximum in the test 5 minutes after termination of the massage. They concluded that the release of beta-endorphins is linked with the pain relief and feeling of warmth and well-being associated with the treatment (Kaada & Torsteinbo 1989).

Connective tissue manipulation

The original technique described by Dicke (1953) and more recently by Ebner (1975) and Holey (1995) involves particular strokes in very specific directions and patterns throughout the entire body depending on the pathology. The authors’ use of CTM is based upon Dicke’s technique in theory and practice, but the technique has been modified for the CPP population specifically. In this text, CTM will be described as the authors utilize it in practice, which has not been described previously.

Evaluation

• Severity of connective tissue (CT) restrictions correlate to severity of symptoms;

• Mild tissue restrictions will cause slight tissue irritation when compressed for long periods;

• Moderate restrictions may cause a hypersensitivity to touch;

• Severely restricted tissue can cause pain without touch, stretch or compression and/or skin fissures.

• Small amount of massage cream;

• Tissue assessed by rolling tissue between tips of thumbs and fingers;

• Thumbs slide underneath CT while fingers grasp tissue and pull towards thumb;

• Tips of fingers used, not pads, therefore short fingernails are required;

• Grasp is firm and fairly superficial;

• Pressure to skin is minimal;

• Direction of force is parallel to tissue, not perpendicular;

Less restricted tissue is easier to mobilize, more restricted tissue is more difficult:

Treatment

Patient response

• Report of cutting or scratching sensation or feeling of dull pressure;

• Severely restricted tissue is very painful;

• Severity of tension correlates to severity of response;

• As tissue mobility improves treatment becomes less painful;

• Patient may report dizziness, nausea, increased sweating, or, in a minority of patients, even fainting (Bischof & Elmiger 1963, Ebner 1975, Frazer 1978);

• Often patients will report an immediate relief in visceral or myofascial pain or dysfunction (Ebner 1975, Gifford & Gifford 1988).

Tissue response

• ‘Triple response’, in this order: appearance of a red line, red flush in tissue if stroke is repeated, slight swelling called a wheal (Lewis 1927);

• First reaction always occurs if there is tension in CT, last two reactions occur depending on strength of stimulus and number of repetitions on area;

• Skin response will lessen as tension in CT decreases;

• Bruising somewhat common in first 2–4 treatments;

Special considerations

• Overweight patients will have more tension;

• Older patients will have looser CT;

• Certain anatomic sites will have more or less tension;

• Imperative to educate patient about what to expect during and after treatment.

Box 11.2.1 • Physiological characteristics of connective tissue and subcutaneous panniculosis

Important physiological functions of areolar, or loose connective tissue

• Binds structures and holds them in their anatomical space

• Stores fat and helps conserve body heat

• Aids in tissue repair and forms scar tissue

• Involved in nutrient and metabolite exchange between vessels and individual cells

• Fibroblasts and mast cells inversely related to suprarenal hormones (water retention)

Symptoms of subcutaneous panniculosis (Dicke 1953, Ebner 1975)

• Hypersensitivity to touch (i.e. vestibulitis)

• Intolerance to tight-fit clothing such as underwear

• Pain during tissue compression (i.e. pain with sitting)

• Pain upon stretch (i.e. posterior thigh pain during a hamstring stretch)

• Cutaneous pain without provocation (i.e. unprovoked vulvodynia)

• Itching (i.e. vulvar itching in the absence of infection)

• Poor tissue integrity (i.e. skin tearing during intercourse)

Physiological effects of connective tissue manipulation

(Ebner 1975, Travell & Simons 1993, Butler 2004, Kotarinos 2008)

The pudendal nerve in chronic pelvic pain

As discussed in Chapter 2, the pudendal nerve supplies the majority of the pelvic floor musculature, the skin of the genitals and peri-anus, and a portion of the rectum, vagina and urethra (for a comprehensive review see Hibner et al. 2010). It is a mixed nerve, featuring both autonomic and somatic components; therefore, it carries motor, sensory and autonomic fibres affecting both the afferent and efferent pathways (Gray & Williams 1995). Due to its autonomic fibres, a patient with pudendal neuralgia could experience sympathetic symptoms such as an increase in heart rate, decreased mobility of the large intestine, constricted blood vessels, dilated pupils, piloerection, perspiration, or an increase in blood pressure (Reitz et al. 2003).

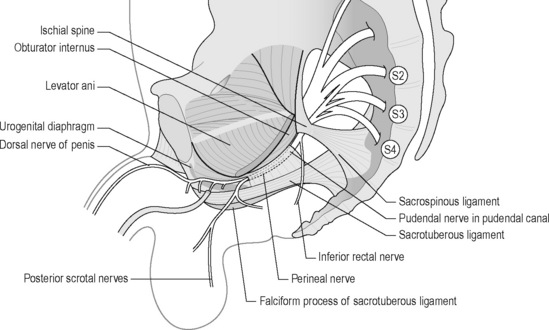

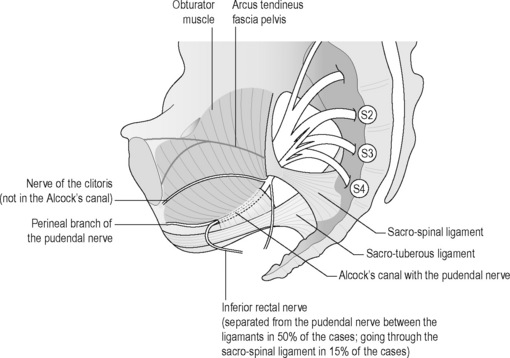

The pudendal nerve arises from the sacral nerve roots 2, 3 and 4 and has three branches: the perineal nerve, the inferior rectal nerve and the dorsal nerve to the clitoris or penis (Robert et al. 1998, Benson & Griffis 2005) (Figure 11.2.4). It runs through three main regions: the gluteal region, the pudendal canal and the perineal region (Thoumas et al. 1999).

Figure 11.2.4 • S2, S3 and S4: sacral roots forming the pudendal nerve.

Adapted from Beco (2004) Pudendal nerve decompression in perineology: a case series. BMC Surg. 4, 1–17

The dorsal nerve to the clitoris or penis innervates the skin of the penis or clitoris.

Yet, there is no general consensus regarding the precise anatomy of the nerve, although it is widely agreed that it enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen, hooks around the sacrospinous ligament near its attachment to the ischial spine, enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen and passes through the ischioanal fossa to Alcock’s canal (Figures 11.2.4, 11.2.5, 11.2.6). Anatomical studies have indicated that the pudendal nerve either gives rise to the inferior rectal branch before or after Alcock’s canal (Robert et al. 1998). This anatomical variation is critical when considering decompression surgery of the pudendal nerve. After Alcock’s canal the pudendal nerve further divides into two terminal branches: the perineal nerve and the dorsal nerve to the clitoris or penis (Figure 11.2.4, 11.2.5, 11.2.6) (Robert et al. 1998).

Pudendal neuralgia

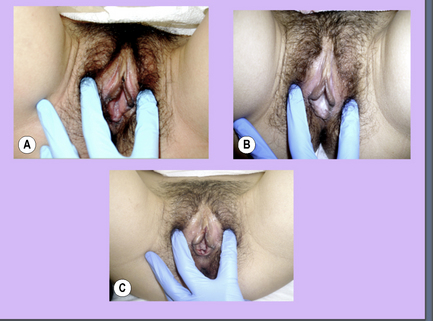

Additionally, upon palpation of the pudendal nerve per vagina and/or anus, the patient should report tenderness and/or pain in the distribution of the nerve (positive Tinel’s sign) (Tinel 1978, Hibner et al. 2010) (Figure 11.2.5).

There are four primary mechanisms from which pudendal neuralgia can develop.

The first is via a tension injury. This occurs when the pudendal nerve is overstretched or repetitively stretched to the point of injury. Common examples include constipation, strenuous squatting exercises (see Chapter 6) and childbirth (Kiff et al. 1984, Snooks et al. 1990).

The second mechanism is through compression. Horseback riding, or prolonged sitting compress the pudendal nerve creating an ischaemic environment which eventually leads to a loss of conduction (see discussion of cycling in Chapter 6). If the nerve is chronically compressed, it results in venous stasis, increased vascular permeability, oedema and scar formation (Benson & Griffis 2005).

The third mechanism of injury is surgical insult or acute injury. Occasionally the pudendal nerve can incur injury during surgical procedures such as pelvic reconstruction procedures or hysterectomies. In rare cases, the pudendal nerve can be injured after a fall (Benson & McClellan 1993).

Lastly, pudendal neuralgia can develop due to the visceral–somatic interaction. Through this reflex, visceral disturbances, such as chronic bladder infections and chronic yeast infections, can contribute to pudendal neuralgia (Head 1893, Bischof & Elminger 1963, Beal 1985, Giamberardino et al. 2005, Giamberardino 2008).

Pudendal nerve entrapment

The aetiology of pudendal nerve entrapment (PNE) is unclear and two scoring systems have been described to positively diagnose the condition (Table 11.2.1). Bautrant et al. (2003a) suggested that a positive diagnosis of PNE must include one major and two minor criteria or two major criteria and lack of other painful cause such as (endometriosis, cyst, etc.).

Table 11.2.1 • Scoring systems described to positively diagnose pudendal nerve entrapment

| Major criteria | Minor criteria |

|---|---|

| Pain in the territory of the nerve | Neuropathic pain |

| Positive Tinel’s sign | Pain aggravated by sitting |

| Positive anaesthetic block | Existence of an aetiological factor or trigger |

Labat et al. (2008) emphasize that the diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia by PNE is essentially clinical. They state that only the operative finding of nerve entrapment and post-operative pain relief can formally confirm PNE as the cause of the neuralgia.

Labat et al. (2008) go on to describe the five Nantes criteria suggestive of a diagnosis of pudendal neuralgia by PNE:

• Pain in the anatomic territory of the pudendal nerve;

• The patient is not woken at night by the pain;

The aetiology is unclear, but PNE may occur secondary to an elongated ischial spine which rotates the sacrospinous ligament. Robert et al. (1998) and Antolak et al. (2002) hypothesize that hypertrophy of the pelvic floor causes the ischial spine to elongate; see Chapter 6. Two areas of potential nerve entrapment have been described in the literature (Robert et al. 1998, Antolak et al. 2002, Bautrant et al. 2003b). The most common site of entrapment is between the sacrospinous and sacrotuberous ligaments: the ‘clamp’ (Bautrant et al. 2003b). The second position of entrapment is in Alcock’s canal, compressed by the falciform process (the medial portion of the sacrotuberous ligament) or by the thickened obturator internus fascia (Robert et al. 1998) (Figure 11.2.6).

Possible consequences of pudendal neuralgia

Pudendal neuralgia is associated with an array of impairments due to the nerve’s vast presence throughout the pelvic floor (Robert et al. 1998, Benson & Griffis 2005). Pudendal neuralgia and/or entrapment can cause pelvic floor muscle dysfunction, connective tissue restrictions and neural mechanosensitivity (Beco 2004, Maigne 1996). Neurodynamics refers to integrated biomechanical, physiological and morphological functions of the nervous system (Shacklock 1995a, Butler 2000, Shacklock 2005). A well-functioning nervous system must be able to undergo particular mechanical events such as elongation, sliding, cross-sectional change, angulation and compression. If the nervous system is unable to tolerate these mechanical events, it is vulnerable to neural oedema, ischaemia, fibrosis and hypoxia which can alter neurodynamics (Shacklock 1995, Butler 2000).

The blood supply of the pudendal nerve can be compromised by surrounding connective tissue restrictions or muscles such as the obturator internus, piriformis, gluteals or pelvic floor muscles (Butler 1991). The nerve’s neurobiomechanics can become compromised through structural or soft tissue changes, involving the ischial spine, the obturator fascia or the sacrospinous ligament, causing stretch, compression, or fixation along mechanical interfaces (Butler 1991, Shacklock 1995, Shafik 2002). Pudendal neuralgia can contribute to pelvic floor muscle hypertonus which can cause structural and biomechanical abnormalities to develop (Baker 1993). Due to the range of symptoms associated with pudendal neuralgia or entrapment and the impact of the symptoms on a patient’s life, coupled with the challenges of a successful treatment programme, patients who suffer from pudendal neuralgia often also suffer from depression and/or anxiety (Mauillon et al. 1999). Lastly, as discussed in depth in Chapter 3, central sensitization is another impairment that often co-occurs with a neuropathic pain syndrome such as pudendal neuralgia.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of pudendal nerve dysfunction include pain with sitting, urinary dysfunction, bowel dysfunction, sexual dysfunction, burning, shooting, stabbing genital and/or anal pain, feeling of fullness in the rectum or vagina, and decreased pain while sitting on a toilet (Robert et al. 1998). The pain during sitting is secondary to the irritated or inflamed pudendal nerve being compressed; hence, when sitting on a toilet, the pain is decreased because the same area is not being compressed. Urinary dysfunction can include hesitancy, urgency, frequency, dysuria and nocturia (Fitzgerald & Kotarinos 2003). Bowel dysfunction can include dyschezia and constipation. Sexual dysfunction for women can include dyspareunia, dysorgasmia and aorgasmia (Basson et al. 2010); for men, post-ejaculatory pain or erectile dysfunction. The feeling of fullness in the vagina or rectum is a result of pelvic floor muscle hypertonus. When irritated, the pudendal nerve causes hypertonus of the muscles it innervates.

Evaluation

As described in Chapter 8, many pelvic pain diagnoses do not dictate a standard treatment protocol. Instead, an appropriate treatment plan comes after a thorough physical examination to identify impairments that may be causal of pelvic pain, and in this case, pudendal neuralgia.

In addition to these five components, a clinician must also palpate the pudendal nerve for tenderness and/or a positive Tinel’s sign (Figure 11.2.5). Palpation of the pudendal nerve is done digitally per vagina and/or anus. The nerve is most commonly palpated at the ischial spine and within Alcock’s canal, but can also be palpated at the dorsal clitoral/penile branch and the inferior rectal branch:

• Pudendal nerve palpation (see Chapter 13 for further detail regarding practical anatomy palpation);

• Ischial spine: palpate bony prominence of ischial spine in lower lateral section of vagina/rectum;

• Alcock’s canal: find obturator internus by resisting hip external rotation, rotate finger medially;

• Dorsal clitoral/penile branch: follow inferior pubic rami to portion of ramus that is level with the clitoris/base of penis, flex distal interphalangeal joint and palpate;

Treatment

Neural mobilization

Bridging (Figure 11.2.8)

Case study 11.2.1

• Duration of symptoms: 10+ years

Decrease in pelvic floor muscle hypertonus, increase in CT mobility in thighs and gluteals, improved vulval colour.

Decrease in pelvic floor muscle hypertonus, increase in CT mobility in thighs and gluteals, improved vulval colour. Patient noted considerable decrease in unprovoked vaginal pain, decrease in pain with sitting, slight decrease in vestibule and clitoral hypersensitivity

Patient noted considerable decrease in unprovoked vaginal pain, decrease in pain with sitting, slight decrease in vestibule and clitoral hypersensitivity Pelvic floor muscles starting to normalize, but unstable, CT mobility continues to improve, colour of vulvar tissues and clitoris improving (Figure 11.2.10B) vestibule had less hypersensitivity with Q-tip testing, dorsal clitoral branch mobility improving

Pelvic floor muscles starting to normalize, but unstable, CT mobility continues to improve, colour of vulvar tissues and clitoris improving (Figure 11.2.10B) vestibule had less hypersensitivity with Q-tip testing, dorsal clitoral branch mobility improving Patient tolerance to sitting and walking improving, vaginal pain minimal, vulvar and clitoral hypersensitivity decreasing

Patient tolerance to sitting and walking improving, vaginal pain minimal, vulvar and clitoral hypersensitivity decreasing Colour of vulvar tissues and clitoris improved, minimal vestibule sensitivity, pelvic floor muscles within normal limits

Colour of vulvar tissues and clitoris improved, minimal vestibule sensitivity, pelvic floor muscles within normal limits Patient reported mild hypersensitivity of vulva and clitoris, mild sitting discomfort, mild to moderate discomfort with arousal and walking

Patient reported mild hypersensitivity of vulva and clitoris, mild sitting discomfort, mild to moderate discomfort with arousal and walking Colour of vulvar tissue improved dramatically (Figure 11.2.10C), minimal to zero sensitivity in vestibule

Colour of vulvar tissue improved dramatically (Figure 11.2.10C), minimal to zero sensitivity in vestibuleAntolak S., et al. Anatomical basis of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the ischial spine and pudendal nerve entrapment. Med. Hypothesis. 2002;59(3):349-353.

Baker P.K. Musculoskeletal origins of chronic pelvic pain. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am.. 1993;20(4):719-742.

Basson R., et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J. Sex. Med.. 2010;7(1 Pt. 2):314-326.

Bautrant E., et al. New Method for the treatment of pudendal neuralgia. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod.. 2003;32:705-712.

Bautrant E., DeBisshop E., Vaini-es V. Modern algorithm for treating pudendal neuralgia: 212 cases and 104 decompressions. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Biol. Reprod.. 2003;32:705-712.

Beal M.C. Viscerosomatic reflexes: a review. J. Am. Osteopath. Assoc.. 1985;85(12):786-801.

Beco J. Pudendal nerve decompression in perineology: a case series. BMC Surg.. 2004(4):1-17.

Benson J.T., Griffis K. Pudenal neuralgia, a severe pain syndrome. Obstet. Gynecol.. 2005;192:1663-1668.

Benson J.T., McClellan E. The effect of vaginal dissection on the pudendal nerve. Obstet. Gynecol.. 1993;82:387-389.

Bischof I., Elmiger G. Connective tissue massage. In: Licht S., editor. Massage, Manipulation and Traction. Huntingdon, New York: Krieger, 1963.

Brattbert G. Connective tissue massage in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Eur. J. Pain. 1999;3(3):235-244.

Butler D.S. Mobilisation of the Nervous System. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1991.

Butler D. Mobilization of the nervous system. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2004.

Butler D.S. The Sensitive Nervous System. Adelaide, Australia: Noigroup Publications; 2000.

Chaitow L. Modern Neuromuscular Techniques. second ed. 2003. Elsevier

Chaitow L. Modern Neuromuscular Techniques, third ed. Edinburgh: Elsevier; 2010.

Craggs M. Pelvic somato-visceral reflexes after spinal cord injury: Measures of functional loss and partial preservation. Prog. Brain Res.. 2005(152):205-219.

Dicke E. Meine Bindegewebmassage. Stuttgart: Marquardt; 1953.

Ebner M. Connective Tissue Massage: Theory and Therapeutic Application. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1975.

Fitzgerald M.P., Kotarinos. Rehabilitation of the short pelvic floor part 1 and 2. Int. J. Urogyn.. 2003;14(4):269-275.

Fitzgerald M.P., Anderson R., Potts J., et al. Randomized multicenter feasibility trial of myofascial physical therapy for the treatment of urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes. J. Urol.. 2009;182(2):570-580.

Frazer F.W. Persistent post-sympathetic pain treated by connective tissue massage. Physiotherapy. 1978;64(7):211-212.

Giamberardino M.A. Women and visceral pain: are the reproductive organs the main protagonists? Mini-review at the occasion of the “European Week Against Pain in Women 2007. Eur. J. Pain. 2008;12(3):257-260.

Giamberardino M.A., et al. Relationship between pain symptoms and referred sensory and trophic changes in patients with gallbladder pathology. Pain. 2005;114(1–2):239-249.

Gifford J., Gifford L. Connective tissue massage. In: Wells P.E., Framptom V., Bowsher D., editors. Pain: Management and Control in Physiotherapy. London: Heinemann Medical, 1988. Chapter 14

Goats, G.C., Keir, K.A., Connective tissue massage. Br. J. Sports Med. 25 (3), 131?133

Grainger H.G. The somatic component in visceral disease. Academy of Applied Osteopathy 1958 Yearbook. 1958. Newark, Ohio

Gray H., William P.L., Bannister L.H. Gray’s anatomy: the anatomical basis of medicine and surgery. thirty-eighth ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1995.

Head H. On disturbances of sensation with especial reference to the pain of visceral disease. Brain. 1893(16):1-130.

Hibner M., et al. Pudendal neuralgia. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol.. 2010;17:148-153.

Holey L.A. Connective tissue manipulation: towards a scientific rationale. Physiotherapy. 1995(80):730-739.

Howard F. Diagnosis and management of pelvic pain. Philapdelphia: Lippincott, Williams &Wilkins; 2000.

Kaada B., Torsteinbo O. Increase of plasma beta endorphins in connective tissue massage. Gen. Pharmacol.. 1989;20(4):487-489.

Kiff E.S., Barnes P.R., Swash M. Evidence of pudendal neuropathy in patients with perineal descent and chronic straining stool. Gut. 1984;25:1279-1282.

Korr I.M. Skin resistance patterns associated with visceral disease. Fed. Proc.. 1949;8:87.

Labat J.J., Riant T., Robert R., et al. Diagnostic criteria for pudendal neuralgia by pudendal nerve entrapment (Nantes criteria). Neurourol. Urodyn.. 2008;27(4):306-310.

Lewis T. The blood vessels of the human skin and their responses. London: Shah; 1927.

Maddali-Bongi S., Del Rosso A., Galluccio F. Efficacy of connective tissue massage and McMennell joint manipulation in the rehabilitative treatment of the hands in systemic sclerosis. Clin. Rheumatol.. 2009;28(10):1167-1173.

Maigne R. Thoraco-lumbar junction syndrome: a source of diagnostic error. J. Ortho. Med.. 1995(17):84-89.

Maigne R. Diagnosis and Treatment of pain of vertebral origin. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

Mauillon J., et al. Results of pudendal nerve neurolysis-transposition in twelve patients suffering from pudendal neuralgia. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1999;42(2):186-192.

Reitz A., et al. Autonomic dysreflexia in response to pudendal nerve stimulation. Spinal Cord. 2003;41:539-542.

Robert R., et al. Anatomic basis of chronic perineal pain: role of the pudendal nerve. Surg. Radiol. Anat.. 1998;20:93-98.

Shacklock M.O. Clinical applications of neurodynamics. In: Shacklock M.O., editor. Moving in on Pain. Chatswood, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995:123-131.

Shacklock M.O. Clinical Neurodynamics: A New System of Neuromusculoskeletal Treatment. Oxford, UK: Butterworth-Heinemann; 2005.

Shafik A. Pudendal canal syndrome: a cause of chronic pelvic pain. Urology. 2002;60(1):199.

Snooks S.J., Swash M., Mathers S.E., Henry M.M. Effect of vaginal delivery on the pelvic floor: a 5-year follow-up. Br. J. Surg.. 1990;77:1358-1360.

Takahashi Y., Nakajima Y. Dermatomes in the rat limbs as determined by antidromic stimulation of the C-fibers in spinal nerves. Pain. 1996(67):197-202.

Thoumas D., et al. Pudendal neuralgia: CT-guided pudendal nerve block technique. Abdom. Imaging. 1999;24:309-312.

Tillman L.J., Cummings G.S. Biologic mechanisms of connective tissue mutability. In: Dynamics of Human Biologic Tissue. Philadelphia: FA Davies; 1992.

Tinel J. The ‘tingling sign’ in peripheral nerve lesions (translated by E.B. Kaplan). In: Spinner M., editor. Injuries to the major branches of peripheral nerves of the forearm. second ed. Phildelphia: WB Saunders; 1978:8-13.

Travell J., Simons D. Myofascial pain and dysfunction, the trigger point manual. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1993. vol. 1 and 2

Wesslemann U., Lai J. Mechanisms of referred visceral pain: uterine inflammation in the adult virgin rat results in neurogenic plasma extravasation in the skin. Pain. 1997(73):309-317.

Wilson P.T. Osteopathic cardiology. Academy of Applied Osteopathy 1956 Yearbook. 1956. Newark, Ohio