109 Connective Tissue and Inflammatory Disorders

• Dry eyes and dry mouth unrelated to a medication side effect suggest primary Sjögren syndrome.

• Loss of sensation, paresthesias, and pain in the digits on exposure to cold or emotional stress are characteristics of Raynaud phenomenon.

• Many patients in whom systemic sclerosis eventually develops are initially found to have symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon and symmetric, nonpitting digital edema (without any fibrosis).

• Gastrointestinal symptoms in the presence of symmetric, digital edema or fibrosis suggest systemic sclerosis.

• Symptoms of edema and fibrosis proximal to the elbows or knees can represent an aggressive, diffuse form of systemic sclerosis with a high likelihood of internal organ involvement.

• An angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor should be considered for hypertensive patients with a presumed or definite diagnosis of systemic sclerosis.

• The diagnosis of sarcoidosis should be suspected in patients with only bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy on chest radiography, especially if they either have long-standing pulmonary complaints or are entirely asymptomatic.

• Early, vague subjective symptoms of fatigue, joint pain, or muscle discomfort may herald autoimmune disease.

Sjögren Syndrome

Pathophysiology

Activation of the innate immune system, possibly in response to environmental or as yet unrecognized infectious triggers, results in elevated levels of type 1 interferon and characteristic cytokine profiles, including increased B-cell–activating factor. The ensuing infiltration of the salivary or lacrimal glands by periductal and periacinar foci of aggressive T lymphocytes marks the adaptive immune response. What follows is destruction and eventual loss of exocrine function.1 In addition to T cells, polyclonal activation of B cells within and at the border of foci can result in hypergammaglobulinemia.

More recently, animal models suggest that lacrimal and salivary gland dysfunction need not always rely on innate and adaptive inflammation as a prerequisite. Rather, they may be related to abnormalities in water and ion channels as a result of genetic, hormonal, or autonomic imbalances antecedent to the inflammatory response.2 Other exocrine glands in the body (lining the respiratory tree, integument, and vagina) can also be affected in Sjögren syndrome and produce a dry cough, dry skin, dysuria, or dyspareunia.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

If dry eyes and dry mouth dominate the clinical picture, the patient may have primary Sjögren syndrome. However, these symptoms can be associated with a number of other autoimmune disorders that more accurately characterize the clinical findings (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma), in which case such patients probably have secondary Sjögren syndrome (Box 109.1).

Box 109.1 Differential Diagnosis of Sjögren Syndrome

Most Common

Medication effects (antihypertensives, antipsychotics, antihistamines, antidepressants)

Viral sialadenitis, human immunodeficiency virus, human T-cell lymphotropic virus type I

Lacrimal gland infiltration in sarcoidosis or amyloidosis

Chronic sialadenitis, conjunctivitis, blepharitis

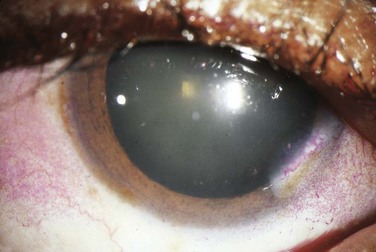

The cracker test, in which the patient tries to chew and swallow a dry cracker, is probably the most useful bedside diagnostic maneuver. Patients with Sjögren syndrome will have a difficult time completing this task, with adherence of food to the buccal mucosa. Slit-lamp testing with fluorescein may show epithelial defects over the cornea consistent with keratitis secondary to dryness. Rose bengal staining (Fig. 109.1) is generally regarded as a more sensitive means of depicting these defects but is usually performed by an ophthalmologist. The Schirmer test involves placing standardized tear testing strips between the unanesthetized eyeball and the lateral margin of the lower lid and noting advancement of a tear film over a period of 5 minutes. Anything less than 5 mm is considered abnormal.

Treatment

Xerophthalmia

Artificial tears with or without preservatives may be used throughout the day, and lubricating ointments can be used at night. Oral pilocarpine, 5 mg four times per day, will stimulate muscarinic gland receptors, increase lacrimal flow, and provide subjective improvement.3,4 More severely affected patients with keratoconjunctivitis sicca who are taking cevimeline, 30 mg three times per day, have reported a reduction in the severity of symptoms.5,6 Topical ocular nonsteroidal and steroidal preparations or topical 0.05% cyclosporine can be prescribed by an ophthalmologist for a short term.5 Occlusion of the nasolacrimal duct temporarily with plugs or permanently by surgical intervention is last-line therapy.

Xerostomia

Though available, artificial saliva tends to be short-lived and less well accepted by patients. Meticulous oral hygiene is necessary to prevent dental caries, gingivitis, or periodontitis secondary to dryness. Sugarless sialogogues (lemon drops) stimulate flow. Lifestyle modifications such as the use of a humidifier or avoidance of dry environments and excessive air conditioning can help retain moisture. Mycostatin oral suspension, Mycostatin vaginal tablets (also dissolve orally), or clotrimazole troches should be considered for the treatment of oral candidiasis in patients with Sjögren syndrome. Oral pilocarpine, 5 mg four times per day, or cevimeline, 30 to 60 mg three times per day, can stimulate muscarinic receptors and improve salivary flow in those with more significant symptoms.5,7–9 One must beware of side effects related to systemic muscarinic activation, including bradycardia, bronchospasm, gastrointestinal symptoms, or impaired mydriasis and trouble with night vision.

Autoimmune Lymphocyte Activity

Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can be prescribed from the emergency department (ED) for symptomatic control of minor rheumatic complaints. Hydroxychloroquine has no clear benefit in ameliorating these symptoms.5 The rheumatologist may prescribe prednisone, methylprednisolone, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, or azathioprine to control lymphocyte activity. Newer therapies include monoclonal antibodies (rituximab) that target B cells.5 Future investigations are directed at blocking type 1 interferon, B-cell–activating factor, and other cytokines that link the initial innate immune response to the subsequent adaptive response composed of activated lymphocytes.

Systemic Sclerosis (Scleroderma)

Epidemiology

Systemic sclerosis is a generalized thickening and fibrosis of the skin and internal organs that affects 1 in 4000 adults in the United States.10 Its incidence ranges from 2 to 23 cases per million per year.11 Women are more likely to be affected than men, with the onset of disease peaking between 30 and 50 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Patients can have localized patches of skin fibrosis, or the disorder may progress to diffuse skin involvement with fibrosis and dysfunction of internal organs. Although the precise trigger is not known, an underlying functional and microstructural vascular abnormality is believed to play a central role. In association with oxygen radical species, findings include endothelial cell dysfunction and apoptosis, an imbalance favoring endothelin over prostacyclin, vascular smooth muscle hyperplasia, and pericyte proliferation in the perivascular space. Concomitantly, an adjacent inflammatory response occurs and is composed of lymphocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts that lay down increasing amounts of extracellular matrix, including collagen.12 Cytokines and growth factors such as transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factor are involved in the amplification of this response, which includes activation and differentiation of fibroblasts.10 The types of systemic sclerosis are listed in Box 109.2.

Box 109.2 Types of Systemic Sclerosis

Localized scleroderma consists of fibrosis in scattered, circular patches of skin (morphea), linear streaks (linear scleroderma), or nodules and is seen primarily in children. There is no systemic or internal organ involvement, and sequelae are cosmetic and sometimes functional.

Limited systemic sclerosis implies that fibrosis occurs distal to the elbows or knees and above the clavicles only. It is generally slowly progressive.

CREST syndrome previously referred to a fibrotic process that involved the skin, digits, and esophageal wall. Patients have calcinosis cutis, Raynaud phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility with symptoms of reflux and dysphagia, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasia. This particular classification is no longer commonly used.

Diffuse systemic sclerosis is characterized by fibrosis extending proximal to the elbows and knees. It may be rapidly progressive and can be associated with significant internal organ fibrosis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Skin findings are the most useful in the ED. Edema is a hallmark of early scleroderma, as well as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and other connective tissue disorders. Painless swelling of the fingers and hands is common (Fig. 109.2). Erythema and pruritus are associated findings caused by an early inflammatory response and deposition of components of the extracellular matrix. Nonpitting edema need not be limited to the distal end of extremities but may spread proximally or to the face and neck over the course of weeks.

Fig. 109.2 Changes in the hands associated with connective tissue diseases.

A, Edematous phase. B, Atrophic phase with contractures and skin thickening (sclerodactyly).

(From Goldman L, Ausiello D, editors. Cecil textbook of medicine. 22nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.)

Fibrosis can ensue in weeks or months. Gradually, collagen is deposited and the edematous areas are replaced by firm, thick, taut skin that may become bound to underlying tissue. In the fingers, tight skin can produce joint flexion contractures plus breaks or ulcerations as it is stretched over bony prominences (knuckles) in the condition termed sclerodactyly (see Fig. 109.2). Digital ulcerations, pitting scars, and loss of the finger pad can result from poor distal perfusion through intervening fibrotic tissue. This may be followed by calcium deposition (calcinosis).

A masklike appearance of the face (Fig. 109.3) with loss of the natural skin creases and diminished hair growth is characteristic. “Salt and pepper” alterations in pigmentation may be present. Disorganized arrays of blood vessels (telangiectases) scattered over the extremities, face, and mucous membranes are sequelae of deranged angiogenesis after the initial vascular obliteration and fibrotic inflammatory response.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis for systemic sclerosis includes several other connective tissue diseases (Box 109.3).

Treatment

Skin therapy includes moisturizers, topical glucocorticoid or antihistamine cream for pruritus, and local wound care with topical antibiotics for ulceration. High- or low-dose D-penicillamine cannot be recommended as an effective treatment at this time.13

Pulmonary hypertension is managed with endothelin receptor antagonists, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and prostacyclin analogues.10,14 Control of interstitial fibrosis has proved more difficult. Aggressive treatment with methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, or other immunosuppressives should be left to a specialist because their benefit is unclear.

Asymptomatic hypertension in a patient with known or suspected systemic sclerosis is presumed to be hyperreninemic in origin secondary to renal arteriolar disease and should be treated as such with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. Oral administration of captopril, 6.25 to 12.5 mg three times per day, is a recommended starting point.15,16 These patients require close outpatient monitoring of renal function. Patients with a hypertensive emergency or malignant hypertension may require intravenous enalaprilat or tighter control of systemic vascular resistance and heart rate via short-acting agents. Dialysis and renal transplantation remain last-line treatments for patients whose condition progresses to end-stage renal disease despite medical management.

Current emerging therapies include intravenous immune globulin, mycophenolate mofetil, B-cell antibodies (rituximab), and autologous or allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to curb the role of immune cells in the pathogenesis of systemic sclerosis. Interferon therapy, downstream tyrosine kinase inhibition, and other novel antifibrotic approaches may be used to limit fibroblast proliferation and collagen production in the future.17

Sarcoidosis

Epidemiology

Because granulomatous inflammation can be due to many causes, the exact worldwide prevalence and incidence of sarcoidosis are not known. Most patients with the disease are younger than 50 years, and the peak age seems to be 20 to 39 years. Women are affected slightly more often than men. Worldwide, the majority of cases occur in white persons in northern European countries, but in the United States the disease is more frequent in African Americans.18

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Skin lesions are present in up to 25% of patients (Fig. 109.4). Most are chronic and due to direct granulomatous involvement of the dermis. Unfortunately, they may take the form of papules, plaques, nodules, keloids at the site of surgical scars, or even lupus pernio (a violaceous discoloration over the nose, cheeks, chin, and ears). Thus it is difficult for the EP to make the diagnosis of sarcoidosis based on the presence of skin lesions alone.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Pulmonary symptoms and typical radiographic signs in a young or middle-aged patient with erythema nodosum, iritis, or nonspecific, symmetric musculoskeletal complaints can help the EP distinguish sarcoidosis from other infectious or autoimmune processes (Table 109.1). Even then, a definitive bedside diagnosis may be difficult to make, and the EP may need to consider tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, community-acquired pneumonia, and lymphoma before diagnosing sarcoidosis (Box 109.4). Some of these patients will have to be admitted or treated empirically for an infectious process before a diagnosis can be secured via a more extensive work-up. Given the array of organ systems affected and the lack of pulmonary symptoms in many patients, sarcoidosis may go unrecognized in the ED.

A chest radiograph is the most useful tool for patients with cough, dyspnea, or chest pain. Patients in whom the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is being considered because of erythema nodosum, iritis, or cranial neuropathy should also undergo chest radiography, even in the absence of pulmonary signs or symptoms. The four stages of pulmonary sarcoidosis are described in Table 109.2. Patients normally do not progress from one stage to the next. A higher stage indicates a lower likelihood of spontaneous resolution.

| Stage I | Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy (Fig. 109.5) |

| Stage II | Bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy plus parenchymal infiltrate |

| Stage III | Parenchymal infiltrate without hilar adenopathy (see Fig. 109.5) |

| Stage IV | Parenchymal fibrosis |

Treatment

Weekly methotrexate and daily azathioprine are corticosteroid-sparing agents that can be prescribed by a pulmonologist or rheumatologist for steroid-dependent patients. Anti–tumor necrosis factor medication may be a future option in severe cases.18,19 Tetracyclines are occasionally used for the treatment of skin lesions.18,20 Radiation therapy and surgical intervention have been used for focal intracranial disease refractory to multiple agents. Lung, heart, or liver transplantation are last-line treatments.

Primary Raynaud Phenomenon

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The cardinal stigmata of autoimmune diseases (sclerodermatous skin changes, muscle weakness, rash) may not be present at the time that a patient has symptoms of Raynaud phenomenon (Box 109.5). A diagnosis of primary Raynaud phenomenon is sometimes made on the initial visit when in actuality the patient later turns out to have secondary Raynaud phenomenon caused by an underlying autoimmunity yet to be manifested.

Treatment

Patients should be instructed to avoid cold and stress, cease tobacco consumption, and wear warm clothing. Oral administration of nifedipine, 10 to 20 mg taken 30 minutes before exposure to cold, can minimize attacks.21 Alternatively, patients may take up to 60 mg/day divided into three doses. Once-a-day extended-release tablets are also available. Caution should be used in the elderly and those with cardiac and vascular disease. One study suggested that the angiotensin receptor blocker losartan (50 mg/day) outperforms nifedipine.22 Prazosin (1 to 2 mg three times daily) and topical nitrates are second-line agents for primary Raynaud phenomenon.23 Endothelin antagonists, phosphodiesterase inhibitors, and intravenous infusions of prostacyclin analogues are newer therapies for severe or secondary Raynaud phenomenon.22,24 Temporary relief of symptoms can be achieved by chemical sympathectomy via local or regional infiltration of an anesthetic. Surgical treatments, including palmar sympathectomy, thoracoscopic cervical sympathectomy, or arteriolysis (release of fibrotic adventitia), are last-line therapy.

Patient Disposition and Next Steps in Care

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

Many connective tissue diseases have associated severe keratitis that may be complicated by globe perforation.

Sarcoid granulomas can block the normal conduction system, with complete heart block being the most common manifestation.

Consider sarcoidosis in patients with only bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy shown on a chest radiograph, especially if they are asymptomatic or have insidious pulmonary complaints.

Before diagnosing sarcoidosis, consider tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, community-acquired pneumonia, and lymphoma. Some of these patients will have to be admitted or treated empirically for an infectious process before a diagnosis can be secured via more extensive work-up.

Patients who have functional impairment and no known history of sarcoidosis will need to be admitted for evaluation of other infectious and neoplastic processes before a definitive diagnosis can be made and treatment started.

1 Mariette X, Gottenberg J. Pathogenesis of Sjogren’s syndrome and therapeutic consequences. Curr Opin Rheum. 2010;22:471–477.

2 Nikolov NP, Illei GG. Pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:465–470.

3 Vivino FB, Al-Hashimi I, Khan Z, et al. Pilocarpine tablets for the treatment of dry mouth and dry eye symptoms in patients with Sjögren syndrome: a randomized, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose, multicenter trial. P92–01 Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:174–181.

4 Tsifetaki N, Kitsos G, Paschides CA, et al. Oral pilocarpine for the treatment of ocular symptoms in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome: a randomised 12 week controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1204–1207.

5 Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas A, Stone JH, et al. Treatment of primary Sjögren’s syndrome: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;304:452–460.

6 Petrone D, Condemi JJ, Fife R, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of cevimeline in Sjögren’s syndrome patients with xerostomia and keratoconjunctivitis sicca. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:748–754.

7 Vivino FB. The treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome patients with pilocarpine-tablets. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 2001;115:1–9.

8 Moutsopoulos NM, Moutsopoulos HM. Therapy of Sjögren’s syndrome. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2001;23:131–145.

9 Fox RI, Petrone D, Condemi J, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of SNI-2011, a novel M3 muscarinic receptor agonist, for treatment of Sjögren’s syndrome [abstract]. Arthritis Rheum. 1998;41:80.

10 Varga J. Systemic sclerosis: an update. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2008;66:198–202.

11 Gabrielli A, Avvedimento E, Krieg T. Scleroderma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1989–2003.

12 Abraham DJ, Krieg T, Distler J, et al. Overview of pathogenesis of systemicsclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48(3 Suppl):iii3–iii7.

13 Clements PJ, Furst DE, Wong WK, et al. High-dose versus low-dose D-penicillamine in early diffuse systemic sclerosis: analysis of a two-year, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1194–1203.

14 Henness S, Wigley F. Current drug therapy for scleroderma and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon: evidence-based review. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2007;19:611–618.

15 Whitman HH, Case DB, Laragh JH, et al. Variable response to oral angiotensin-converting-enzyme blockade in hypertensive scleroderma patients. Arthritis Rheum. 1982;25:241–248.

16 Beckett VL, Donadio JV, Brennan LA, Jr., et al. Use of captopril as early therapy for renal scleroderma: a prospective study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1985;60:763–771.

17 Bournia V, Vlachoyiannopoulos P. Recent advances in the treatment of systemic sclerosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2009;36:176–200.

18 Iannuzzi M, Rybicki B, Teirstein AS. Sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2153–2165.

19 Dempsey O, Paterson E, Kerr KM, et al. Sarcoidosis. BMJ. 2009;339:b3206.

20 Judson M. Sarcoidosis: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and approach to treatment. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:26–33.

21 Thompson AE, Pope JE. Calcium channel blockers for primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: a meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2005;44:145–150.

22 Lambova S, Muller-Ladner U. New lines in therapy of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Rheumatol Int. 2009;29:355–363.

23 Russell IJ, Lessard JA. Prazosin treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon: a double-blind single crossover study. J Rheumatol. 1985;12:94–98.

24 García-Carrasco M, Jiménez-Hernández M, Escárcego RO, et al. Treatment of Raynaud’s phenomenon. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;8:62–68.