4

Conjunctiva and Sclera

Trauma

Foreign Body

Exogenous material on, under, or embedded within the conjunctiva or sclera; commonly dirt, glass, metal, or cilia. Patients usually note foreign body sensation and redness; may have corneal staining, particularly linear vertical scratches due to blinking with a foreign body trapped on the upper tarsal surface. Good prognosis.

• Remove foreign body; evert lids to check tarsal conjunctiva.

• Topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (polymyxin B sulfate-trimethoprim [Polytrim] drops or bacitracin ointment qid).

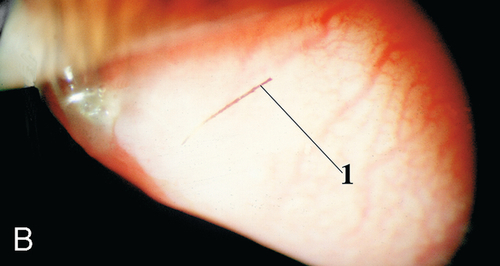

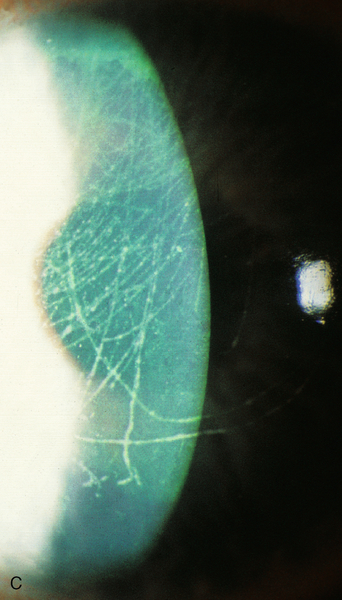

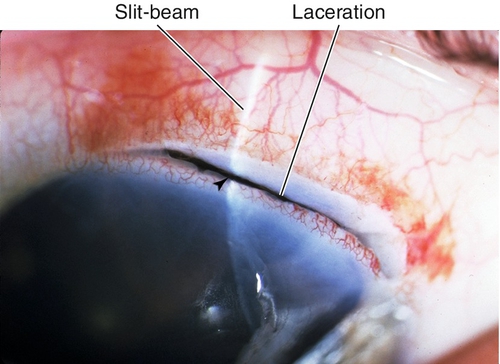

Laceration

Partial-thickness or full-thickness cut in conjunctiva with or without partial-thickness cut in the sclera; very important to rule out open globe (see below); good prognosis.

• Seidel test for suspected open globe (see below).

• Topical broad-spectrum antibiotic (gatifloxacin [Zymar] or moxifloxacin [Vigamox] qid).

• Conjunctival and partial-thickness scleral lacerations rarely require surgical repair.

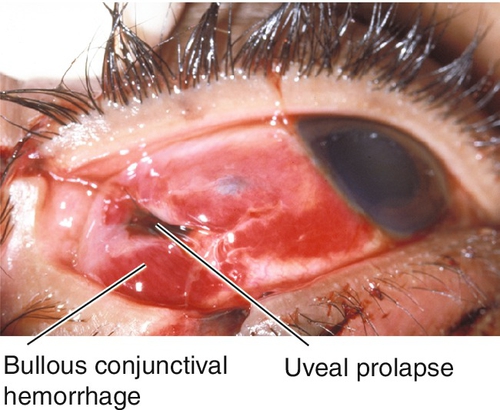

Open Globe

Full-thickness defect in eye wall (cornea or sclera), commonly from penetrating or blunt trauma; the latter usually causes rupture at the limbus, just posterior to the rectus muscle insertions, or at previous surgical incision sites; double penetrating injuries are called perforations; an open globe may also be due to corneal or scleral melting.

Associated signs include lid and orbital trauma, corneal abrasion or laceration, wound dehiscence, positive Seidel test (see Laceration section in Chapter 5), low intraocular pressure, flat or shallow anterior chamber, anterior chamber cells and flare, hyphema, peaked pupil, iris transillumination defect, sphincter tears, angle recession, iridodialysis, cyclodialysis, iridodonesis, phacodonesis, dislocated lens, cataract, vitreous and retinal hemorrhage, commotio retinae, retinal tear, retinal detachment, choroidal rupture, intraocular foreign body or gas bubbles, and extruded intraocular contents. Guarded prognosis.

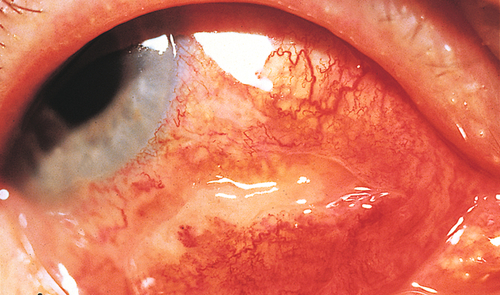

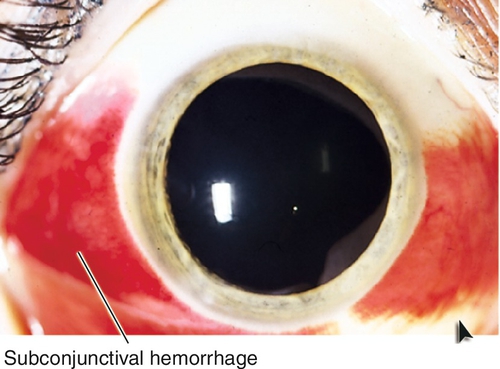

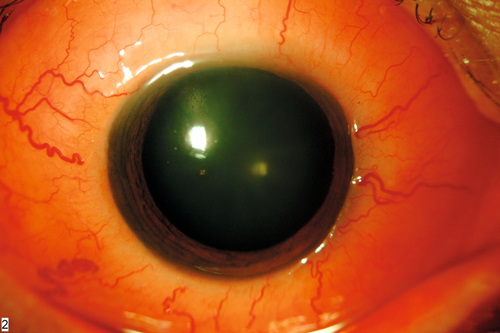

Subconjunctival Hemorrhage

Diffuse or focal area of blood under the conjunctiva. Appears bright red, otherwise asymptomatic. May be idiopathic, associated with trauma, sneezing, coughing, straining, emesis, aspirin or anticoagulant use, or hypertension, or due to an abnormal conjunctival vessel. Excellent prognosis.

• Reassurance if no other ocular findings.

• Consider blood pressure measurement if recurrent.

• Medical or hematology consultation for recurrent, idiopathic, subconjunctival hemorrhages, or other evidence of systemic bleeding (ecchymoses, epistaxis, gastrointestinal bleeding, hematuria, etc.).

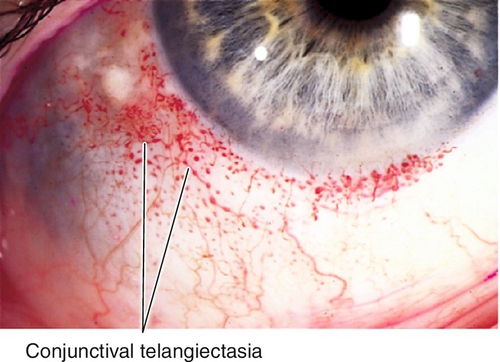

Telangiectasia

Definition

Abnormal, dilated conjunctival capillary formation.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic red spot on eye; patient may have epistaxis and gastrointestinal bleeding depending on etiology.

Signs

Telangiectasia of conjunctival vessels, subconjunctival hemorrhage.

Differential Diagnosis

Idiopathic, Osler–Weber–Rendu syndrome, ataxia–telangiectasia, Fabry’s disease, Sturge–Weber syndrome.

Evaluation

• Consider CT scan for multisystem disorders.

• Medical consultation to rule out systemic disease.

Prognosis

Usually benign; may bleed; depends on etiology.

Microaneurysm

Definition

Focal dilation of conjunctival vessel.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may notice red spot on eye.

Signs

Microaneurysm; may have associated retinal findings.

Differential Diagnosis

Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, sickle cell anemia (Paton’s sign), arteriosclerosis, carotid occlusion, fucosidosis, polycythemia vera.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to conjunctiva and ophthalmoscopy.

• Check blood pressure.

• Lab tests: Fasting blood glucose (diabetes mellitus), sickle cell prep, hemoglobin electrophoresis (sickle cell).

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Usually benign.

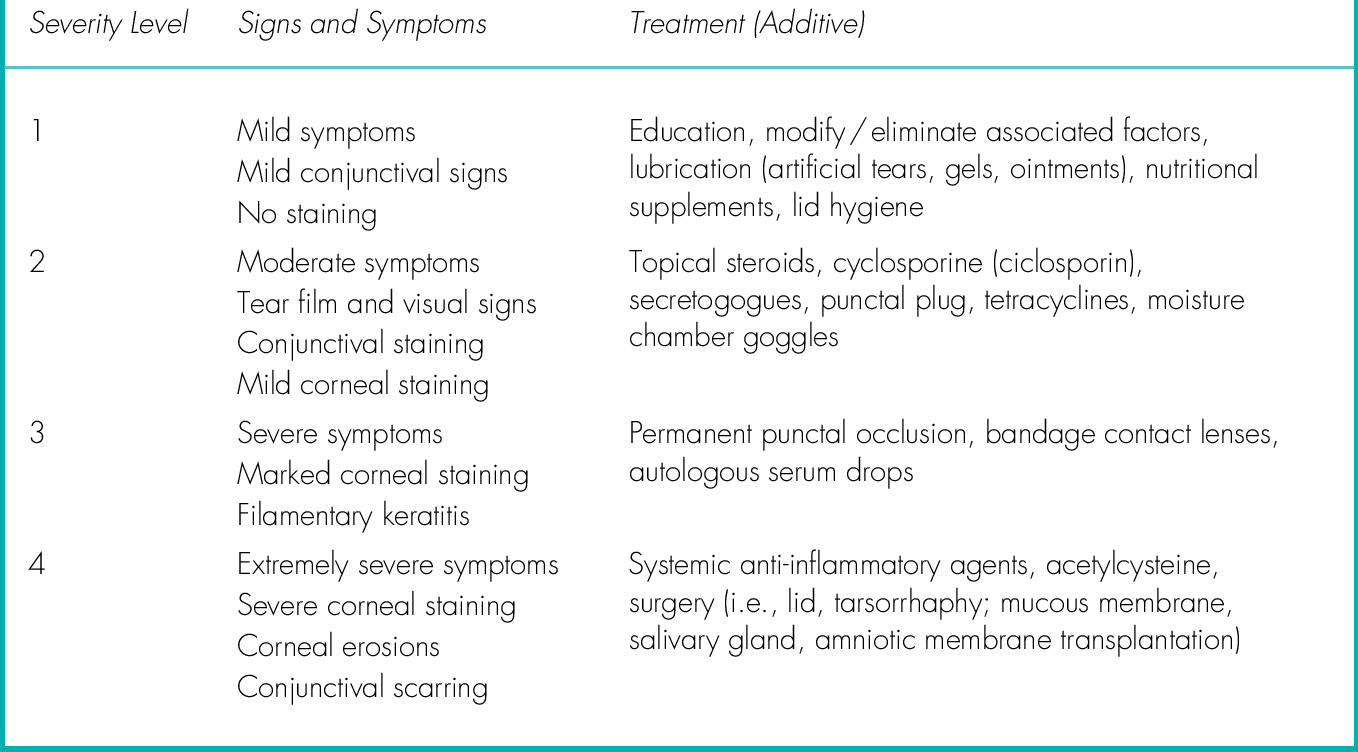

Dry Eye Disease (Dry Eye Syndrome, Keratoconjunctivitis Sicca)

Definition

Sporadic or chronic ocular irritation with visual disturbance due to a tear film and ocular surface abnormality.

Etiology

Any condition that causes a deficiency or imbalance in the aqueous, lipid, or mucin components of the tear film. Dry eye can be classified by mechanism (decreased tear production or increased tear evaporation), category (lid margin disease [i.e., blepharitis, meibomitis], no lid margin disease, altered tear distribution/clearance), or severity (Table 4-1). It is usually multifactorial with an inflammatory component; tear hyperosmolarity and tear film instability create a cycle of ocular surface inflammation, damage, and symptoms.

Aqueous-Deficient Dry Eye

Characterized by abnormal lacrimal gland function causing decreased tear production.

Sjögren syndrome

Dry eye, dry mouth, and arthritis with autoantibodies (to Ro (SSA) and / or La (SSB) antigens) and no connective tissue disease (primary, > 95% female) or with connective tissue disease, including rheumatoid arthritis and collagen vascular diseases (secondary).

Non-Sjögren

Hypofunction of the lacrimal gland due to other causes:

Primary lacrimal gland deficiencies

Age-related (historically labeled KCS), congenital alacrima, familial dysautonomia (Riley Day syndrome).

Secondary lacrimal gland deficiencies

Lacrimal gland infiltration, lymphoma, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, AIDS, graft-versus-host disease, lacrimal gland ablation or denervation.

Obstruction of the lacrimal ducts

Cicatrizing conjunctivitis (Stevens–Johnson syndrome, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, trachoma, chemical burns, radiation).

Neurosecretory block

Sensory (corneal surgery, contact lens wear, diabetes, neurotrophic keratopathy), motor (cranial nerve VII damage, systemic medications (β-blockers, antimuscarinics, antidepressants, diuretics)).

Evaporative Dry Eye

Characterized by normal lacrimal gland function but increased tear evaporation.

Intrinsic causes

Meibomian gland dysfunction (MGD)

Primary, secondary, simple, or cicatricial (see Meibomitis and Acne Rosacea sections in Chapter 3).

Lid / globe abnormalities

Conditions that result in a malposition, lagophthalmos, or proptosis with exposure of the ocular surface (see Exposure Keratopathy in Chapter 5).

Reduced blink rate

Reading/computer work (decreases blink rate by up to 60%), Parkinson’s disease.

Medications

Systemic retinoids (Accutane).

Extrinsic causes

Malnutrition or malabsorption causes conjunctival xerosis and night blindness (nyctalopia) with progressive retinal degeneration; major cause of blindness worldwide.

Topical drugs

Anesthetics, preservatives (BAK – benzalkonium chloride).

Contact lens wear

Approximately 50% of contact lens wearers have dry eye symptoms.

Ocular surface disease

Cicatrizing conjunctivitis (see above), allergic conjunctivitis.

Epidemiology

Dry eye disease is estimated to affect 5–30% of the population ≥ 50 years old and is more common in women. Associated factors include age, hormone levels (menopause, androgen deficiency), environmental conditions (low humidity, wind, heat, air-conditioning, pollutants, irritants, allergens), and smoking.

Symptoms

Irritation, dryness, burning, stinging, grittiness, foreign body sensation, tearing, red eye, discharge, blurred or fluctuating vision, photophobia, contact lens intolerance, increased blinking; symptoms are variable and exacerbated by wind, smoke, and activities that reduce the blink rate (i.e., reading and computer work).

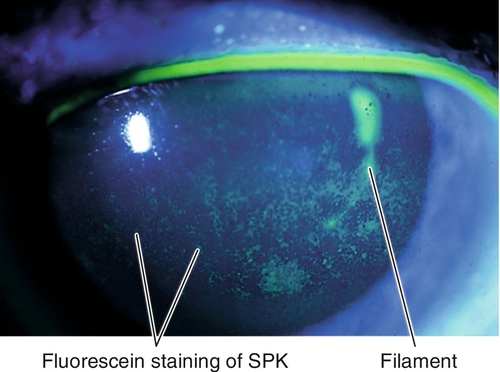

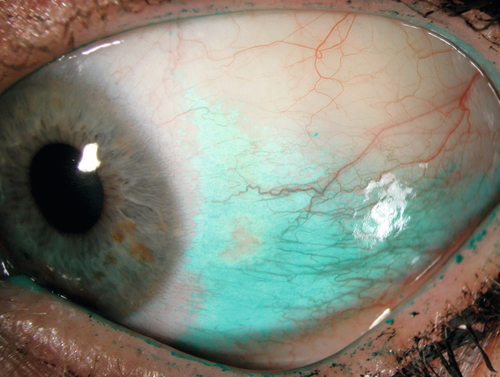

Signs

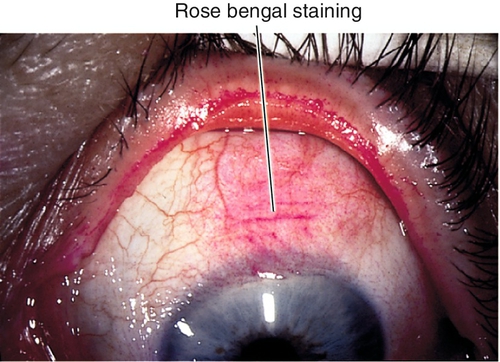

Conjunctival injection, decreased tear break-up time (< 10 seconds), decreased tear meniscus height (< 0.20 mm), excess tear film debris, corneal filaments, dry corneal surface, irregular and dull corneal light reflex, corneal and/or conjunctival staining with lissamine green, rose bengal, and fluorescein (typically in the interpalpebral space or on the inferior cornea); may have Bitot’s spot (white, foamy patch of keratinized bulbar conjunctiva [pathognomonic for vitamin A deficiency]), conjunctivochalasis (loosened bulbar conjunctiva resting on lid margin); severe cases can cause corneal ulceration, descemetocele, or perforation. May also have signs of an underlying condition (i.e., rosacea, blepharitis, lid abnormality).

Differential Diagnosis

See above; also allergic conjunctivitis, medicamentosa, contact lens overwear, trichiasis.

Evaluation

• Complete eye exam with attention to lids, tear film (break-up time and height of meniscus), conjunctiva, and cornea (staining with lissamine green or rose bengal [dead and degenerated epithelial cells], and/or fluorescein [only dead epithelial cells]).

• Schirmer’s test: Two tests exist, but they are usually not performed as originally described. One is done without and one is done with topical anesthesia. The inferior fornix is dried with a cotton-tipped applicator, and a strip of standardized filter paper (Whatman #41, 5 mm width) is placed in each lower lid at the junction of the lateral and middle thirds. After 5 minutes, the strips are removed and the amount of wetting is measured. Normal results are 15 mm or greater without anesthesia (basal + reflex tearing), and 10 mm or greater with topical anesthesia (basal tearing). Schirmer’s test often produces variable results so its usefulness may be limited.

• Alternatively, consider the phenol red thread test: Similar to the Schirmer’s test but uses a special cotton thread that changes color as tears are absorbed for 30 seconds; less irritating and may be more reproducible.

• Lab tests: Consider tear lactoferrin and lysozyme (decreased), matrix metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) (> 40 ng/mL), tear osmolarity (> 316 mOsm / L), and impression cytology (detects reduced goblet cell density and squamous metaplasia; rarely used clinically).

• Consider corneal topography (computerized videokeratography): Irregular or broken mires with resulting abnormal topography and blank areas due to poor-quality tear film and dry spots. Surface regularity index (SRI) value correlates with severity of dry eye.

• Electroretinogram (reduced), electro-oculogram (abnormal), and dark adaptation (prolonged) in vitamin A deficiency.

• Consider medical consultation for systemic diseases.

Prognosis

Depends on underlying condition; severe cases may be difficult to manage.

Inflammation

Definition

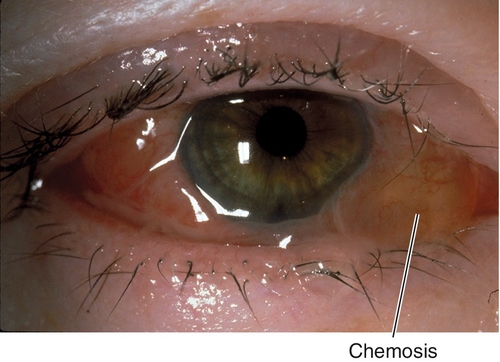

Chemosis

Edema of conjunctiva; may be mild with boggy appearance or massive with tense ballooning.

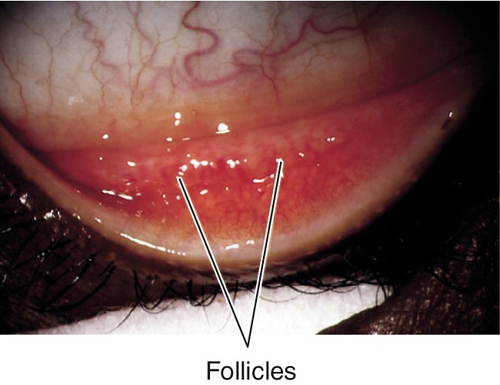

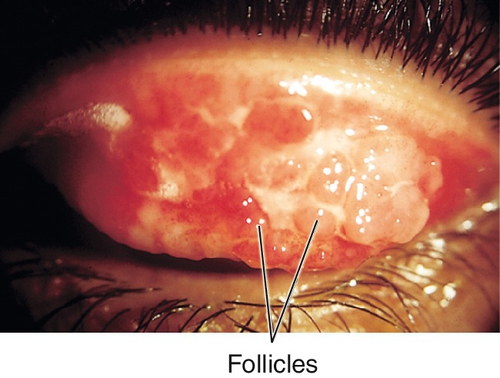

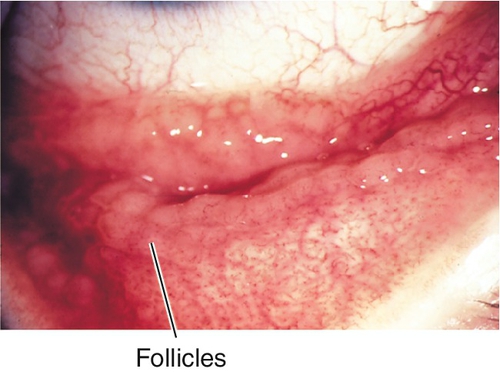

Follicles

Small, translucent, avascular mounds of plasma cells and lymphocytes found in epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC), herpes simplex virus, chlamydia, molluscum, or drug reactions.

Granuloma

Collection of giant multinucleated cells found in chronic inflammation from sarcoid, foreign body, or chalazion.

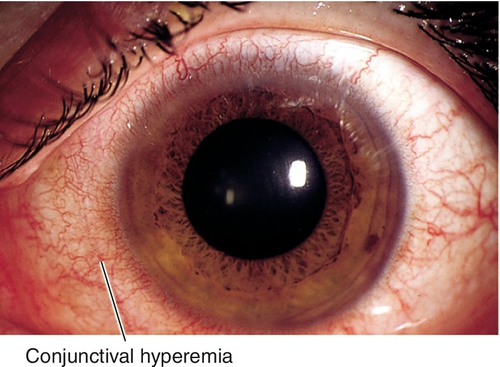

Hyperemia

Redness and injection of conjunctiva.

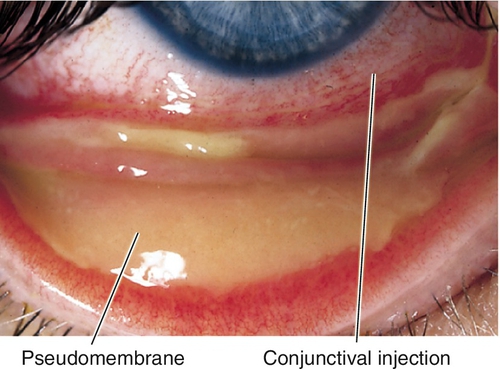

Membranes

A true membrane is a firmly adherent, fibrinous exudate that bleeds and scars when removed; found in bacterial conjunctivitis (Streptococcus species, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Corynebacterium diphtheriae), Stevens–Johnson syndrome, and burns. A pseudomembrane is a loosely attached, avascular, fibrinous exudate found in EKC and mild allergic or bacterial conjunctivitis.

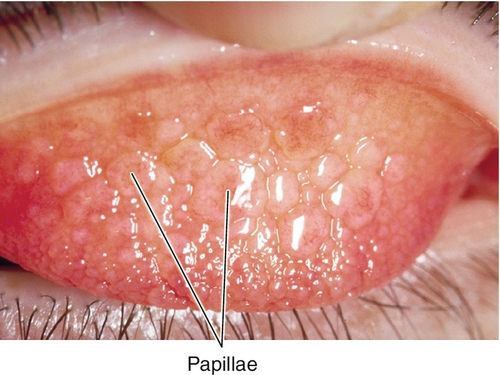

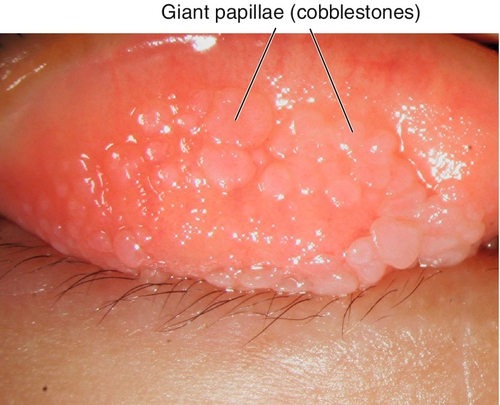

Papillae

Vascular reaction consisting of fibrovascular mounds with central vascular tuft; nonspecific finding in any conjunctival irritation or conjunctivitis; can be large (“cobblestones” or giant papillae).

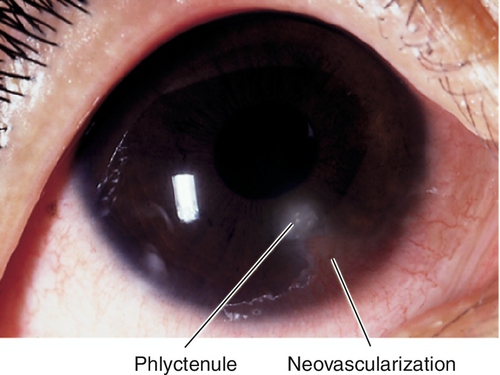

Phlyctenule

Focal, nodular, vascularized infiltrate of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and lymphocytes with central necrosis due to hypersensitivity to Staphylococcus species, Mycobacterium species, Candida species, Coccidioides, Chlamydia, or nematodes; located on the bulbar conjunctiva or at the limbus; can march across the cornea, causing vascularization and scarring behind the leading edge.

Symptoms

Red eye, swelling, itching, foreign body sensation; may have discharge, photophobia, and tearing.

Signs

See above; depends on type of inflammation.

Differential Diagnosis

Any irritation of conjunctiva (allergic, infectious, autoimmune, chemical, foreign body, idiopathic).

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Cultures and smears of conjunctiva, cornea, and discharge for infectious causes.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; most are benign and self-limited (see Conjunctivitis section below).

Conjunctivitis

Definition

Infectious or noninfectious inflammation of the conjunctiva classified as acute (shorter than 4 weeks’ duration) or chronic (longer than 4 weeks’ duration).

Acute Conjunctivitis

Infectious

Gonococcal

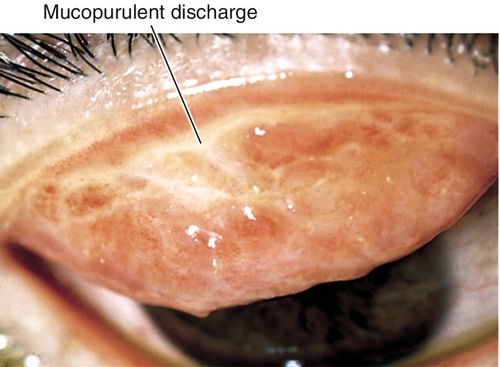

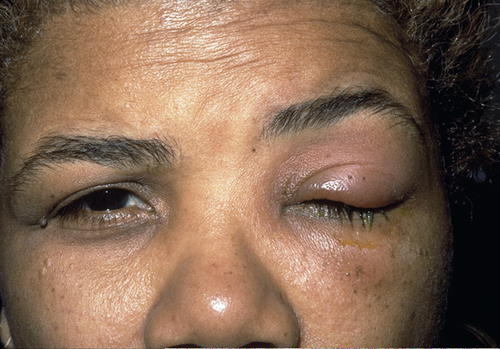

Hyperacute presentation with severe purulent discharge, chemosis, papillary reaction, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and lid swelling. N. gonorrhoeae can invade intact corneal epithelium and cause infectious keratitis (see Chapter 5).

Nongonococcal bacterial

Seventy percent due to Gram-positive organisms, 30% due to Gram-negative organisms; usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus species, or Moraxella catarrhalis. Spectrum of clinical presentations ranging from mild (signs include minimal lid edema, scant purulent discharge) to moderate (significant conjunctival injection, membranes); usually no preauricular lymphadenopathy or corneal involvement. Most common cause of acute conjunctivitis in children under 3 years old (50–80%).

Adenoviral

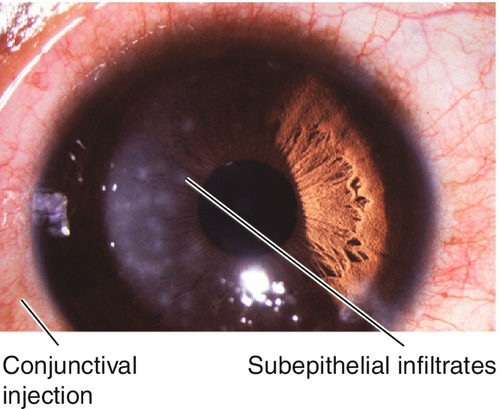

Most common cause of viral conjunctivitis (“pink eye”); signs include lid edema, serous discharge, pseudomembranes; may have preauricular lymphadenopathy and corneal subepithelial infiltrates. Transmitted by contact and contagious for 12–14 days; 51 serotypes, 1 / 3 associated with eye infection:

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis (EKC)

Caused by types 8, 19, and 37.

Pharyngoconjunctival fever

Caused by types 3, 4, 5, and 7.

Nonspecific follicular conjunctivitis

Caused by types 1–11 and 19.

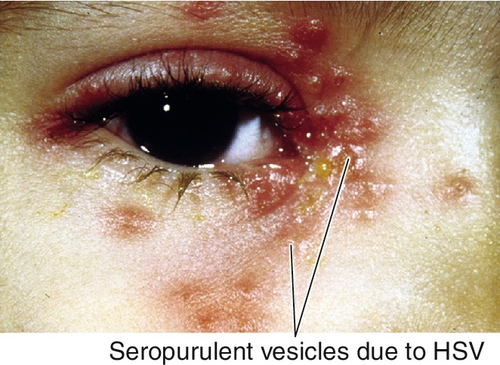

Herpes simplex virus

Primary disease in children causes lid vesicles; may also have fever, preauricular lymphadenopathy, and an upper respiratory infection.

Herpes zoster virus

Herpes zoster ophthalmicus can cause conjunctival injection, hemorrhages, vesicles, papillary or follicular reaction, membrane or pseudomembrane; may develop ulceration, scarring, and symblepharon; may have other ocular complications (see Chapters 3 and 5).

Pediculosis

Results from contact with pubic lice (sexually transmitted); may be unilateral or bilateral (see Chapter 3).

Allergic

Seasonal

Most common (50% of allergic conjunctivitis); occurs in individuals of all ages; associated with hay fever, airborne allergens (i.e., pollen).

Atopic keratoconjunctivitis

Rare (3% of allergic conjunctivitis); occurs in adults; not seasonal; associated with atopy (rhinitis, asthma, dermatitis). Similar features as vernal keratoconjunctivitis but papillae usually smaller and conjunctiva has milky edema; also thickened and erythematous lids, corneal neovascularization, cataracts (10%), and keratoconus.

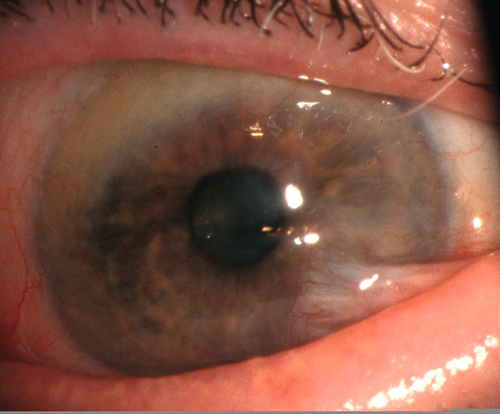

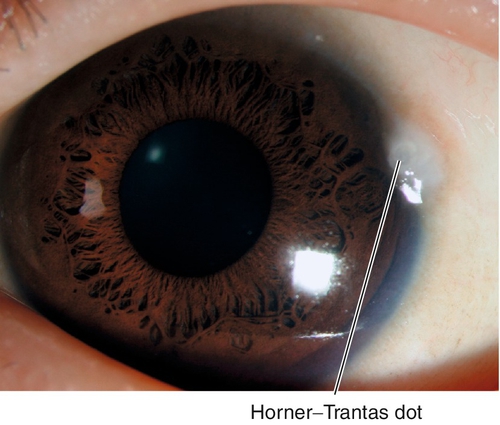

Vernal keratoconjunctivitis

Very rare (< 1% of allergic conjunctivitis); occurs in children; seasonal (warm months); male predilection; lasts 5–10 years, then resolves. Associated with family history of atopy; signs include intense itching, ropy discharge, giant papillae (cobblestones), Horner–Trantas dots (collections of eosinophils at limbus), shield ulcer, and keratitis (50%). Histologically, more than two eosinophils per high-power field is pathognomonic.

Toxic

Follicular reaction due to eye drops (especially neomycin, aminoglycoside antibiotics, antiviral medications, atropine, miotic agents, brimonidine [Alphagan], apraclonidine [Iopidine], epinephrine, and preservatives including contact lens solutions [i.e., thimerosal]).

Chronic Conjunctivitis

Infectious

Chlamydial

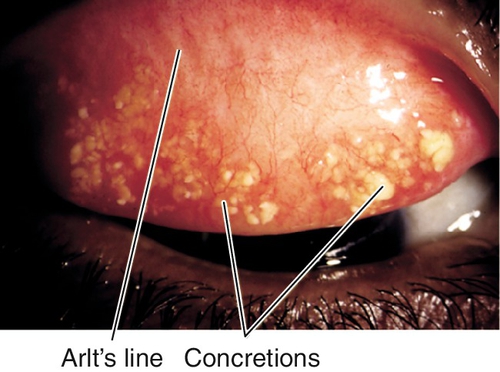

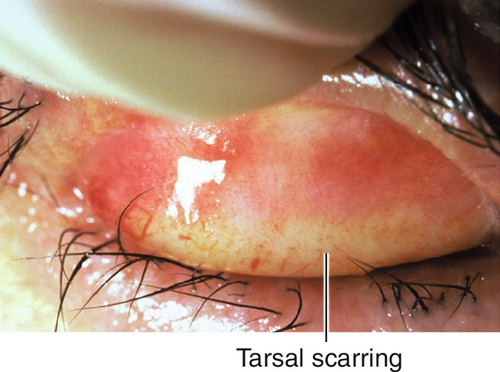

Leading cause of blindness worldwide; caused by serotypes A–C. Signs include follicles, Herbert’s pits (scarred limbal follicles), superior pannus, superficial punctate keratitis, upper tarsal scarring (Arlt’s line).

Figure 4-24 Trachoma demonstrating linear pattern of upper tarsal scarring. Also note the abundant concretions that appear as yellow granular aggregates.

Inclusion conjunctivitis

Caused by serotypes D–K. Signs include chronic, follicular conjunctivitis, subepithelial infiltrates, and no membrane; associated with urethritis in 5%.

Lymphogranuloma venereum

Caused by serotype L. Associated with Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (see below), conjunctival granulomas, and interstitial keratitis.

Molluscum contagiosum

Usually appears with one or more, umbilicated, shiny papules on the eyelid. Associated with follicular conjunctivitis; with multiple lesions, consider human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (see Chapter 3).

Allergic

Perennial

Occurs in individuals of all ages. Associated with animal dander, dust mites.

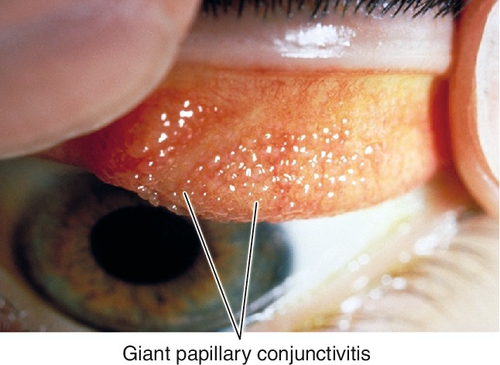

Giant papillary conjunctivitis

Occurs in contact lens wearers (> 95% of giant papillary conjunctivitis cases); also secondary to prosthesis, foreign body, or exposed suture. Signs include itching, ropy discharge, blurry vision, and pain/irritation with contact lens wear.

Figure 4-26 Giant papillary conjunctivitis demonstrating large papillae in upper tarsal conjunctiva.

Toxic

Follicular reaction due to eye drops or contact lens solutions (see above).

Other

Superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis

Occurs in middle-aged females; 50% have thyroid disease; usually bilateral and asymmetric; may be secondary to contact lens use (see Chapter 5). Signs include boggy edema, redundancy and injection of superior conjunctiva, superficial punctate keratitis, filaments, and no discharge; symptoms are worse than signs.

Kawasaki’s disease

Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome of unknown etiology; occurs in children under 5 years old; more common in Japanese. Diagnosis based on 5 of 6 criteria: (1) fever (≥ 5 days), (2) bilateral conjunctivitis, (3) oral mucosal changes (erythema, fissures, “strawberry tongue”), (4) rash, (5) cervical lymphadenopathy, and (6) peripheral extremity changes (edema, erythema, desquamation). Associated with polyarteritis especially of coronary arteries; may be fatal (1–2%).

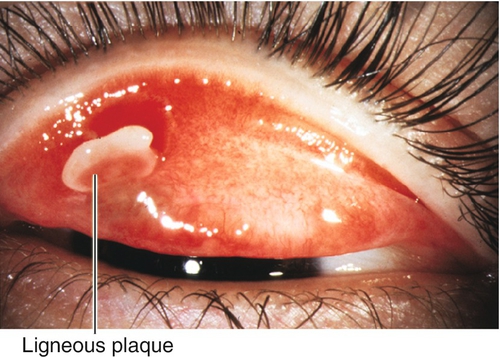

Ligneous

Rare, idiopathic, bilateral, membranous conjunctivitis; occurs in children. A thick, white, woody infiltrate and plaque develops on the upper tarsal conjunctiva.

Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome

Unilateral conjunctivitis with conjunctival granulomas and preauricular/submandibular lymphadenopathy; may have fever, malaise, and rash. Due to cat-scratch fever, tularemia, sporotrichosis, tuberculosis, syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum, Epstein–Barr virus, mumps, fungi, malignancy, or sarcoidosis.

Ophthalmia neonatorum

Occurs in newborns; may be toxic (silver nitrate) or infectious (bacteria [especially N. gonorrhoeae], herpes simplex virus, chlamydia [may have otitis and pneumonitis]).

Symptoms

Red eye, swelling, itching, burning, foreign body sensation, tearing, discharge, crusting of lashes; may have photophobia and decreased vision.

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, lid edema, conjunctival injection, chemosis, papillae, follicles, membranes, petechial hemorrhages, concretions, discharge; may have preauricular lymphadenopathy, tarsal conjunctival filament, subepithelial corneal infiltrates, punctate corneal staining, corneal ulcers, and cataract.

Differential Diagnosis

See above; also blepharitis (may present as “recurrent conjunctivitis”), medicamentosa (toxic reaction commonly associated with preservatives [i.e., benzalkonium chloride (BAK)] in medications, as well as antiviral medications, antibiotics, miotic agents, dipivefrin [Propine], apraclonidine [Iopidine], and atropine), dacryocystitis, nasolacrimal duct obstruction.

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Consider cultures and smears of conjunctiva and cornea (mandatory for suspected bacterial cases). Consider RPS Adeno Detector test (for suspected viral cases).

• Consider pediatric consultation.

Prognosis

Usually good; subepithelial infiltrates in adenoviral conjunctivitis cause variable decreased vision for months.

Degenerations

Definition

Secondary degenerative changes of the conjunctiva.

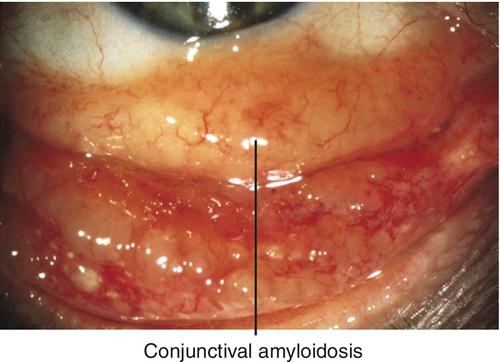

Amyloidosis

Yellow-white or salmon-colored, avascular deposits; may be due to primary (localized) or secondary (systemic) amyloidosis.

Concretions

Yellow-white inclusion cysts filled with keratin and epithelial debris in fornix or palpebral conjunctiva; associated with aging and chronic conjunctivitis; can erode through overlying conjunctiva causing foreign body sensation (see Figure 4-24).

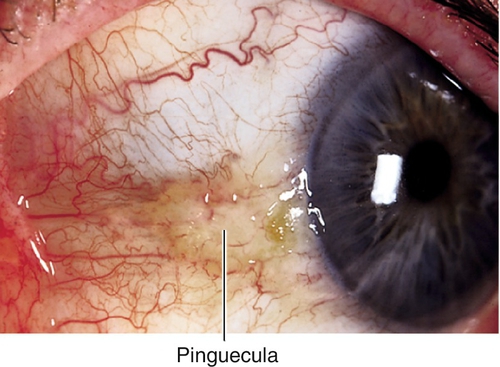

Pinguecula

Yellow-white, subepithelial lesion of abnormal collagen at the medial or temporal limbus; due to actinic changes; elastotic degeneration seen histologically; may become inflamed (pingueculitis); may calcify over time.

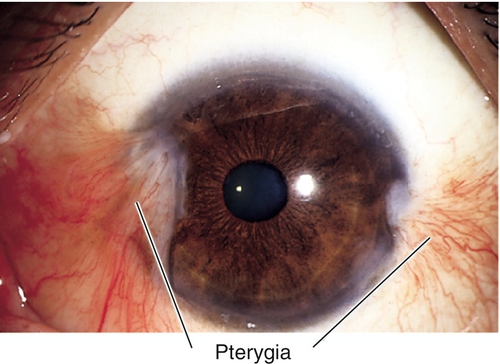

Pterygium

Triangular fibrovascular tissue in interpalpebral space involving cornea; often preceded by pinguecula; destroys Bowman’s membrane; may have iron line at leading edge (Stocker’s line); induces astigmatism and may cause decreased vision.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may have red eye, foreign body sensation, decreased vision; may notice bump or growth; may have contact lens intolerance.

Signs

See above.

Differential Diagnosis

Cyst, squamous cell carcinoma, conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia, episcleritis, scleritis, phlyctenule.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to conjunctiva and cornea.

Prognosis

Good; about one-third of pterygia recur after simple excision, recurrences are reduced by conjunctival autograft, β-irradiation, thiotepa, or mitomycin C.

Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid

Definition

Systemic vesiculobullous disease of mucous membranes resulting in bilateral, chronic, cicatrizing conjunctivitis; other mucous membranes frequently involved, including oral (up to 90%), esophageal, tracheal, and genital; skin involved in up to 30% of cases.

Etiology

Usually idiopathic (probably autoimmune mechanism) or drug induced (may occur with epinephrine, timolol, pilocarpine, echothiophate iodide [Phospholine Iodide], or idoxuridine).

Epidemiology

Incidence of 1 in 20,000; usually occurs in females (2 : 1) over 60 years old; associated with HLA-DR4, DQw3.

Symptoms

Red eye, dryness, foreign body sensation, tearing, decreased vision; may have dysphagia or difficulty in breathing.

Signs

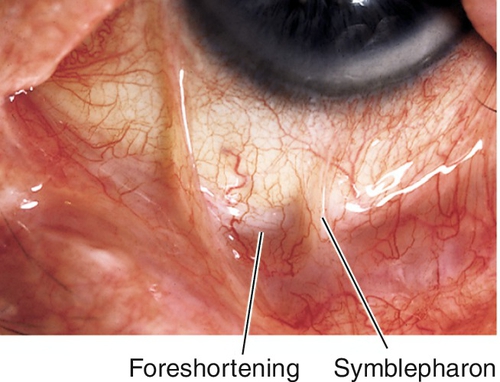

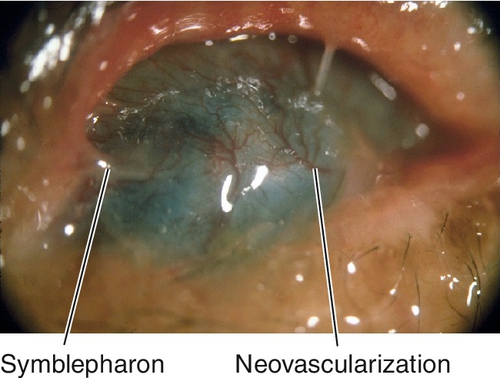

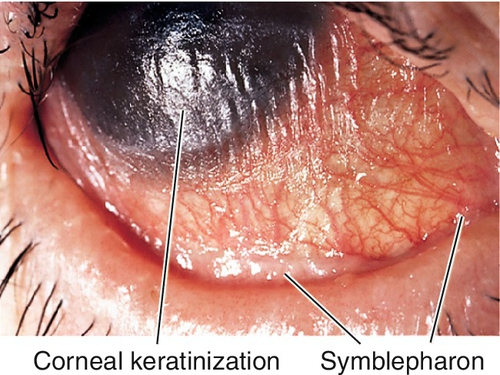

Normal or decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection and scarring, dry eye, symblepharon (fusion or attachment of eyelid to bulbar conjunctiva), ankyloblepharon (fusion or attachment of upper and lower eyelids), foreshortened fornices, trichiasis, entropion, keratitis, corneal ulcer, scarring, and vascularization, conjunctival and corneal keratinization, and oral lesions; corneal perforation and endophthalmitis can occur.

Differential Diagnosis

Stevens–Johnson syndrome, chemical burn, squamous cell carcinoma, scleroderma, infectious or allergic conjunctivitis, trachoma, sarcoidosis, ocular rosacea, radiation, linear immunoglobulin A dermatosis, practolol-induced conjunctivitis.

Evaluation

• Complete ophthalmic history and eye exam with attention to lids, conjunctiva, and cornea.

• Conjunctival biopsy (immunoglobulin and complement deposition in basement membrane).

Prognosis

Poor; chronic progressive disease with remissions and exacerbations, surgery often initiates exacerbations.

Stevens–Johnson Syndrome (Erythema Multiforme Major)

Definition

Acute, usually self-limited (up to 6 weeks), cutaneous, bullous disease with mucosal ulceration resulting in acute membranous conjunctivitis.

Etiology

Usually drug-induced (may occur with sulfonamides, penicillin, aspirin, barbiturates, isoniazid, or phenytoin [Dilantin]) or infectious (herpes simplex virus, Mycoplasma species, adenovirus, Streptococcus species).

Symptoms

Fever, upper respiratory infection, headache, malaise, skin eruption, decreased vision, pain, red eye, swelling, and oral mucosal ulceration.

Signs

Fever, skin eruption (target lesions), mucous membrane ulceration and crusting, decreased visual acuity, conjunctival injection, discharge, membranes, dry eye, symblepharon (fusion or attachment of eyelid to bulbar conjunctiva), trichiasis, keratitis, corneal ulcer, scarring, vascularization, and keratinization.

Differential Diagnosis

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, chemical burn, squamous cell carcinoma, scleroderma, infectious or allergic conjunctivitis, trachoma, sarcoidosis, ocular rosacea, radiation.

Evaluation

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Fair; not progressive (in contrast to ocular cicatricial pemphigoid), recurrences are rare, but up to 30% mortality.

Tumors

Congenital

Hamartoma

Derived from abnormal rest of cells, composed of tissues normally found at same location (e.g., telangiectasia, lymphangioma).

Choristoma

Derived from abnormal rest of cells, composed of tissues not normally found at that location.

Dermoid

White-yellow, solid, round, elevated nodule, often with visible hairs on surface and lipid deposition anterior to its corneal edge; composed of dense connective tissue with pilosebaceous units and stratified squamous epithelium; usually located at inferotemporal limbus; may be part of Goldenhar’s syndrome with dermoids, preauricular skin tags, and vertebral anomalies (see Chapter 5).

Dermolipoma

Similar appearance to dermoid but composed of adipose tissue with keratinized surface; usually located superotemporally extending into orbit.

Epibulbar osseous choristoma

Solitary, white nodule composed of compact bone that develops from episclera; freely moveable; usually located superotemporally.

Epithelial

Cysts

Fluid-filled cavity within the conjunctiva, defined by its lining (ductal or inclusion). Often due to trauma or inflammation, can be congenital.

• Consider excision; must remove inner lining to prevent recurrence.

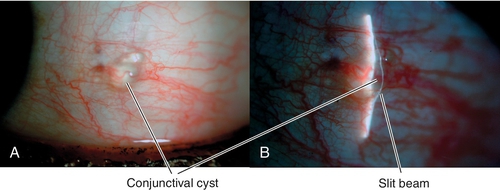

Figure 4-39 Conjunctival inclusion cyst appears as a clear elevation over which the slit-beam bends.

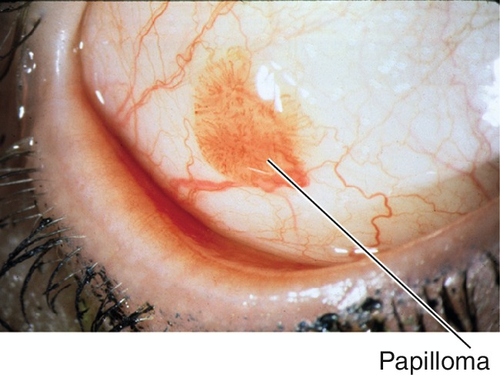

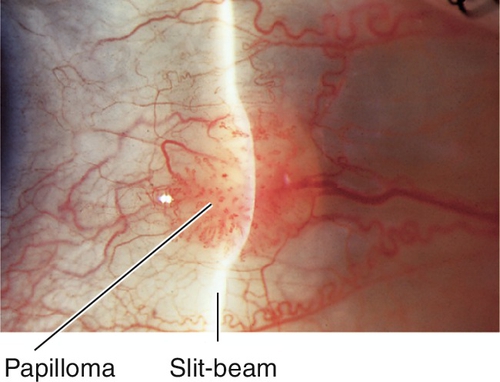

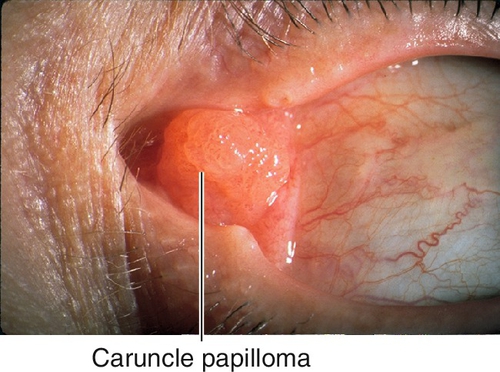

Papilloma

Red, gelatinous lesions composed of proliferative epithelium with fibrovascular cores; may be pedunculated or sessile, solitary or multiple. Often associated with human papillomavirus.

• Consider excision with or without cryotherapy, topical interferon α-2b, or topical mitomycin C.

• Consider oral cimetidine or carbon dioxide laser treatment for recalcitrant cases.

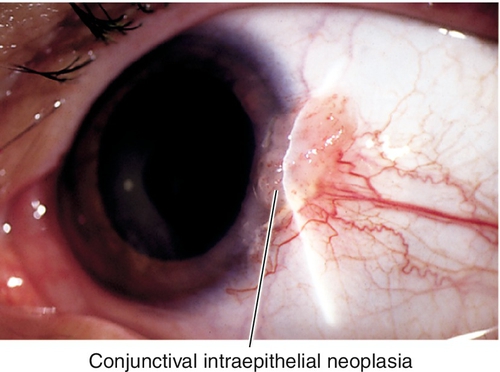

Conjunctival Intraepithelial Neoplasia

White, gelatinous, conjunctival dysplasia confined to the epithelium; usually begins at limbus and is a precursor of squamous cell carcinoma.

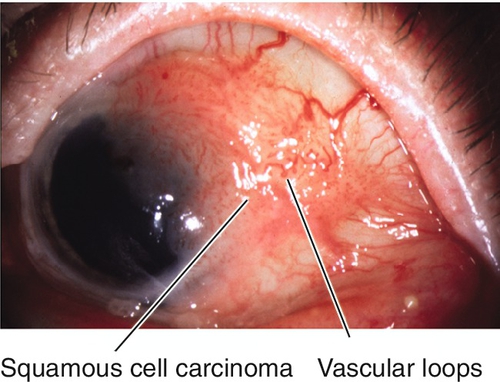

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Interpalpebral, exophytic, gelatinous, papillary appearance with loops of abnormal vessels; may have superficial invasion and extend onto cornea. Most common conjunctival malignancy in the US; more common in elderly, Caucasians (90%), and males (81%); associated with ultraviolet radiation, human papillomavirus, and heavy smoking; suspect AIDS in patients < 50 years of age. Intraocular invasion (2–8%), orbital invasion (12–16%), and metastasis are rare; recurrence after excision is < 10%; mortality rate of up to 8%.

• MRI to rule out orbital involvement if suspected.

• Excisional biopsy with episclerectomy, corneal epitheliectomy with 100% alcohol, and cryotherapy to bed of lesion; should be performed by a cornea or tumor specialist.

• Consider topical 5-fluorouracil, topical mitomycin C, or interferon α-2b (topical or subconjunctival) especially for recurrence.

• Exenteration with adjunctive radiation therapy for orbital involvement.

• Medical consultation and systemic workup.

Melanocytic

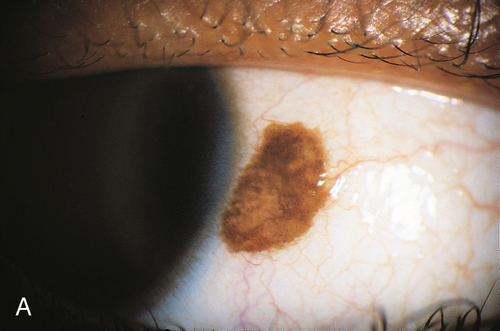

Nevus

Mobile, discrete, elevated, variably pigmented lesion that contains cysts; may be junctional, subepithelial, or compound. May enlarge during puberty; rarely becomes malignant.

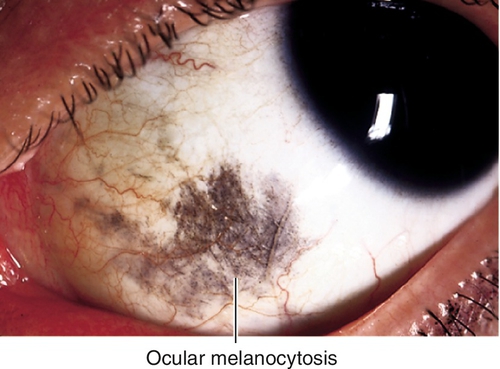

Ocular Melanocytosis

Unilateral, increased uveal, scleral, and episcleral pigmentation appearing as blue-gray patches. More common in Caucasians.

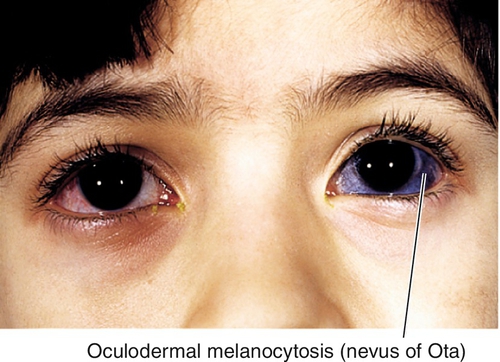

Oculodermal Melanocytosis (Nevus of Ota)

Increased uveal, scleral, episcleral, and periorbital skin pigmentation; more common in Asians and African-Americans; increased risk of congenital glaucoma; uveal melanoma may rarely develop in Caucasians (see Chapter 10).

• Periodic examinations to monitor for evidence of malignant transformation.

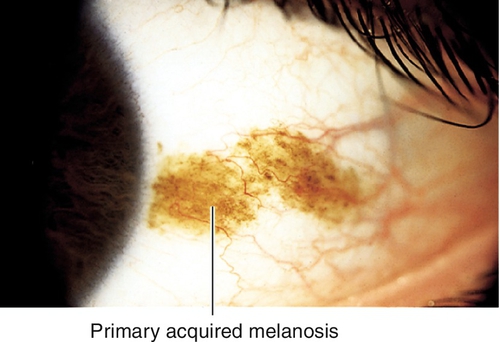

Primary Acquired Melanosis

Mobile, patchy, diffuse, flat, brown lesions without cysts; indistinct margins, may grow and involve the cornea. Occurs in middle-aged Caucasian adults; accounts for 11% of conjunctival tumors and 21% of pigmented lesions. Histologically may have atypia; 13% with severe atypia progress to malignant melanoma.

• Excisional biopsy with cryotherapy.

• Consider topical interferon α-2b or mitomycin C for recurrence.

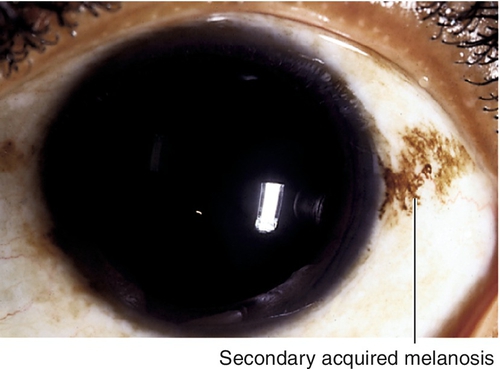

Secondary Acquired Melanosis

Hyperpigmentation due to racial variations, actinic stimulation, radiation, pregnancy, Addison’s disease, or inflammation; may also occur with topical prostaglandin analogues; usually perilimbal.

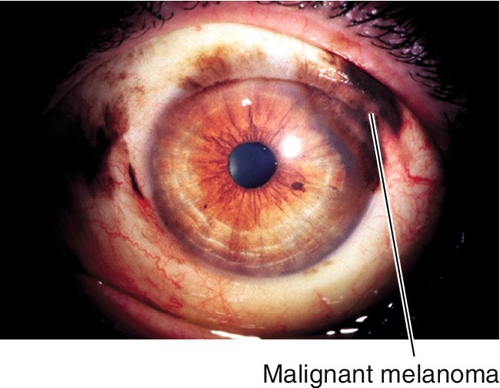

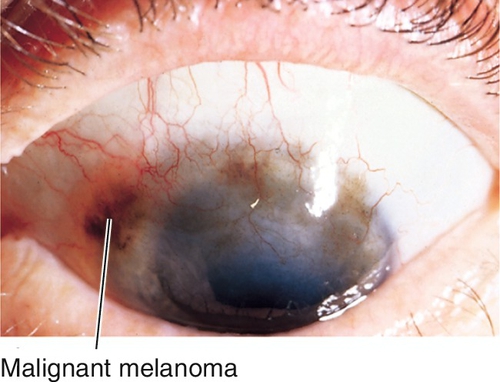

Malignant Melanoma

Nodular, pigmented lesion containing vessels, but no cysts; may arise from primary acquired melanosis (70%), nevus (20%), or de novo (10%). Mainly occurs in middle-aged Caucasian adults; accounts for 2% of ocular malignancies. Twenty-five percent risk of metastasis (to parotid and submandibular nodes first); 25–45% mortality.

• Excisional biopsy using “no touch” technique with episclerectomy, corneal epitheliectomy with 100% alcohol, and cryotherapy (double freeze–thaw); consider topical mitomycin C; should be performed by a cornea or tumor specialist.

• May require exenteration, but does not improve prognosis.

• Medical consultation and systemic workup.

Stromal

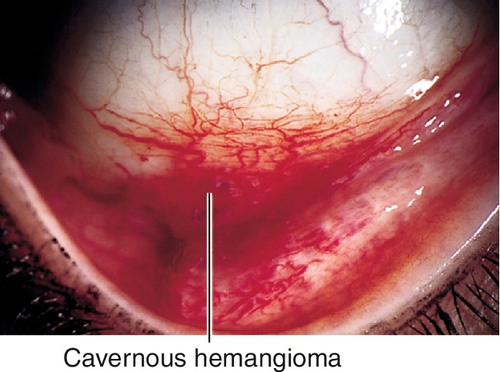

Cavernous Hemangioma

Red patch on conjunctiva; may bleed and be associated with other ocular hemangiomas or systemic disease.

Juvenile Xanthogranuloma

Yellow-orange nodules composed of vascularized, lipid-containing histiocytes; can also involve iris and skin; often regresses spontaneously.

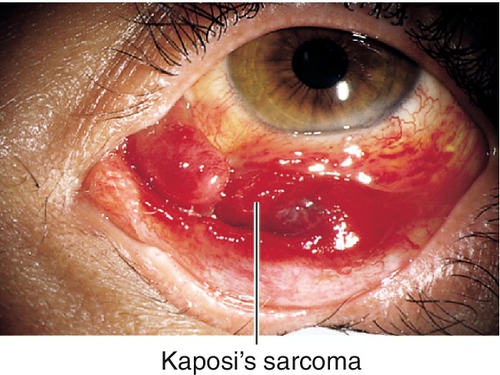

Kaposi’s Sarcoma

Single or multiple, flat or elevated, deep red to purple plaques (malignant granulation tissue); may cause recurrent subconjunctival hemorrhage; may involve orbit; also found on skin. Occurs in immunocompromised individuals, especially HIV-positive patients.

• Medical consultation and systemic workup.

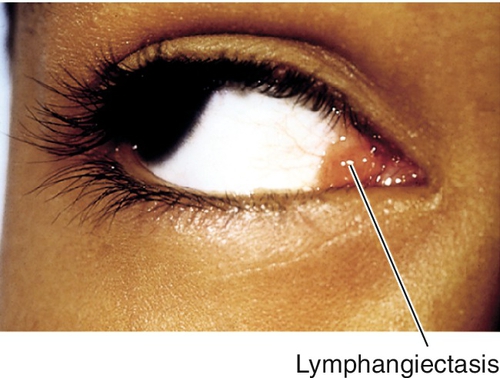

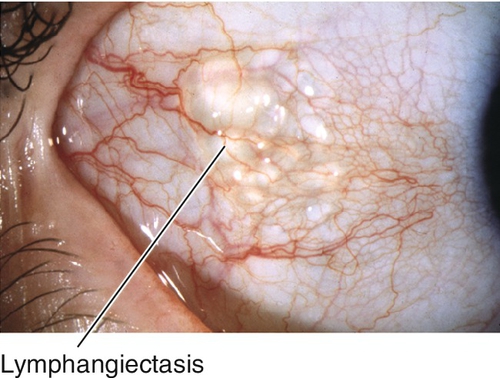

Lymphangiectasis

Cluster of elevated clear cysts that represent dilated lymphatics; may have areas of hemorrhage.

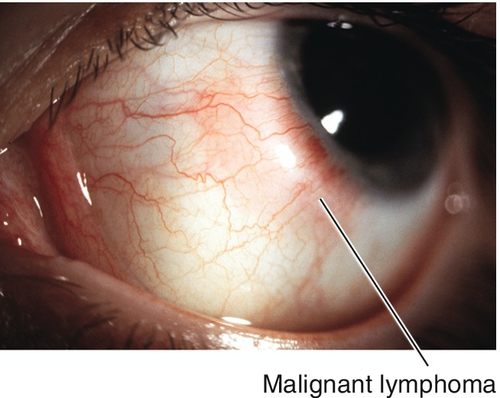

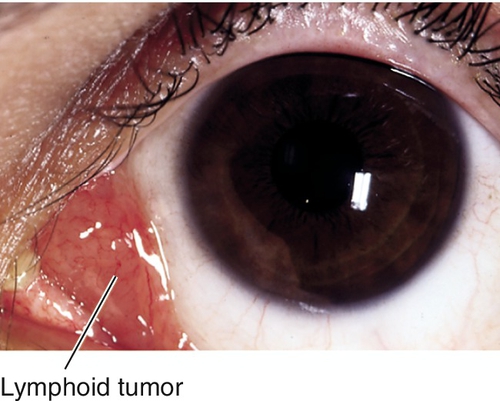

Lymphoid

Single or multiple, smooth, flat, salmon-colored patches. Usually occurs in middle-aged adults. Spectrum of disease from benign reactive lymphoid hyperplasia to malignant lymphoma (non-Hodgkin’s; less aggressive MALT [mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue] or more malignant non-MALT); may involve orbit, may develop systemic lymphoma (see Chapter 1).

• External beam radiation for lesion limited to conjunctiva.

• May require systemic chemotherapy.

• Medical and oncology consultations and systemic workup.

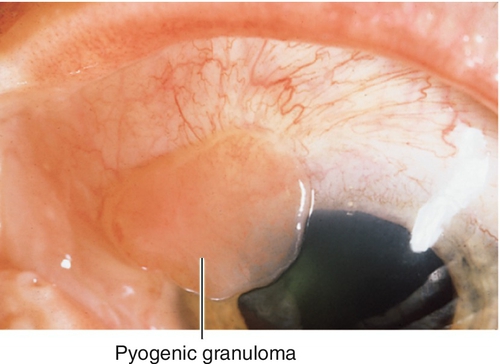

Pyogenic Granuloma

Red, fleshy, polypoid mass at the site of chronic inflammation; often follows surgical or accidental trauma. Misnomer, because it is neither pyogenic nor a granuloma, but rather granulation tissue.

• Consider excision.

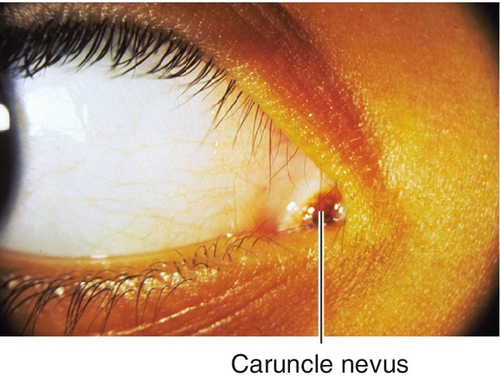

Caruncle

Tumors that affect the conjunctiva may also occur in the caruncle, including (in order of frequency): papilloma, nevus, inclusion cyst, malignant melanoma, also sebaceous cell carcinoma, and oncocytoma (oxyphilic adenoma; fleshy, yellow-tan cystic mass from transformation of epithelial cells of accessory lacrimal glands; slowly progressive).

• Medical consultation and systemic workup for malignant lesions.

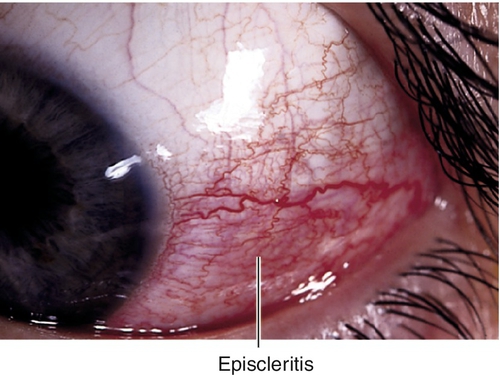

Episcleritis

Definition

Sectoral (70%) or diffuse (30%) inflammation of episclera.

Epidemiology

Eighty percent simple; 20% nodular; 33% bilateral.

Etiology

Idiopathic, tuberculosis, syphilis, herpes zoster, rheumatoid arthritis, other collagen vascular diseases.

Symptoms

Red eye; may have mild pain.

Signs

Subconjunctival and conjunctival injection, usually sectoral; may have chemosis, episcleral nodules, anterior chamber cells and flare.

Differential Diagnosis

Scleritis, iritis, pingueculitis, myositis, phlyctenule, staphylococcal marginal keratitis, superior limbic keratoconjunctivitis.

Evaluation

• Consider scleritis workup (see below) in recurrent or bilateral cases.

Prognosis

Good; usually self-limited; may be recurrent in 67% of cases.

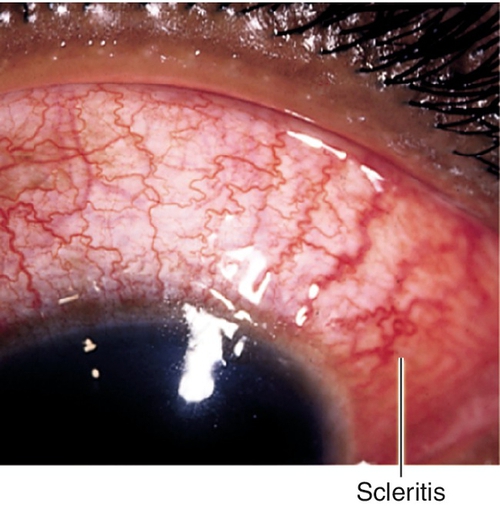

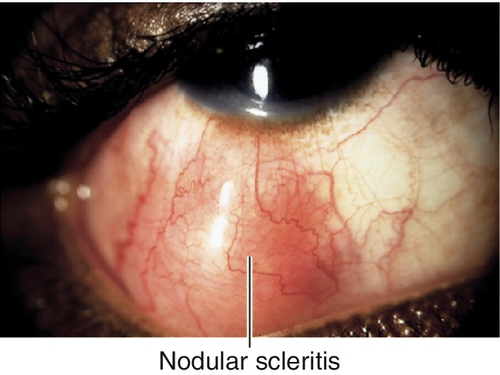

Scleritis

Definition

Inflammation of sclera, can be anterior (98%) or posterior (2%) (see Chapter 10).

Epidemiology

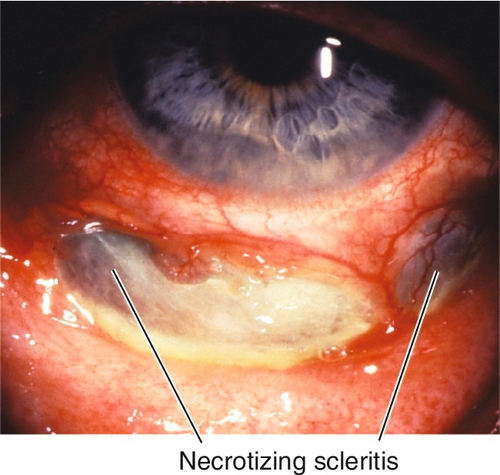

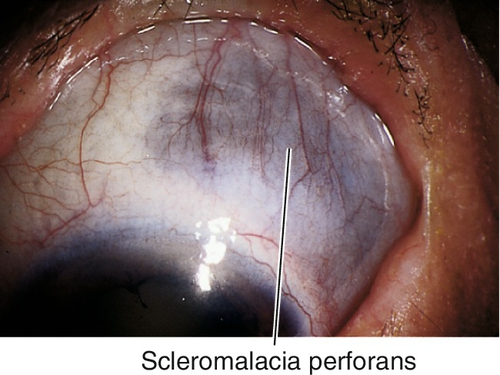

Anterior form may be diffuse (40%), nodular (44%), or necrotizing (14%) with or without (scleromalacia perforans) inflammation; more than 50% are bilateral; associated systemic disease in 50% of cases.

Etiology

Collagen vascular disease in 30% of cases (most commonly rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, polyarteritis nodosa, Wegener’s granulomatosis, and relapsing polychondritis); also herpes zoster, syphilis, tuberculosis, leprosy, gout, porphyria, postsurgical, and idiopathic.

Symptoms

Pain, photophobia, swelling, red eye, decreased vision (except scleromalacia).

Signs

Normal or decreased visual acuity, subconjunctival and conjunctival injection with violaceous hue, chemosis, scleral edema, scleral nodule(s), globe tenderness to palpation; may have anterior chamber cells and flare (30%), corneal infiltrate or thinning, scleral thinning (30%); posterior type may have chorioretinal folds, focal serous retinal detachments, vitritis, and optic disc edema (see Figures 10-170 and 10-171).

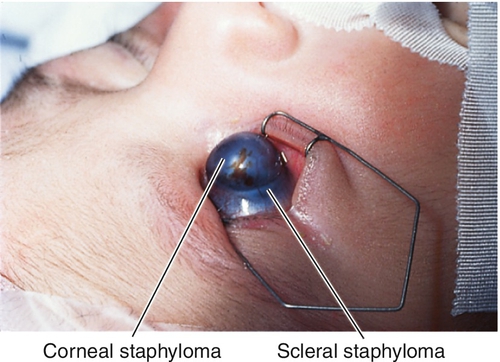

Differential Diagnosis

Episcleritis, iritis, phlyctenule, retrobulbar mass, myositis, scleral ectasia, and staphyloma.

Evaluation

• Lab tests: Complete blood count (CBC), rheumatoid factor (RF), antinuclear antibody (ANA), antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA), Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) test, fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, PPD and controls, and chest radiographs.

• B-scan ultrasonography: Thickened sclera and “T-sign” in posterior scleritis (see Figure 10-172).

• Medical consultation.

Prognosis

Depends on etiology; poor for necrotizing form, which may perforate; scleromalacia perforans rarely perforates; recurrences are common.

Scleral Discoloration

Definition

Alkaptonuria (Ochronosis)

Recessive inborn error of metabolism (accumulation of homogentisic acid) causing brown pigment deposits in eyes, ears, nose, joints, and heart; triangular patches in interpalpebral space near limbus, pigmentation of tarsus and lids.

Ectasia (Staphyloma)

Congenital, focal area of scleral thinning usually near limbus; underlying uvea is visible and may bulge through defect; perforation is uncommon.

Osteogenesis Imperfecta (Autosomal Dominant)

Congenital disorder of type I collagen; mapped to chromosome 17q21.3-22.1 (COL1A1 gene) and chromosome 7 (COL1A2 gene). Sclera is thin and appears blue due to underlying uvea (also found in Ehlers–Danlos syndrome). If patient develops scleral icterus, then the sclera may appear green.

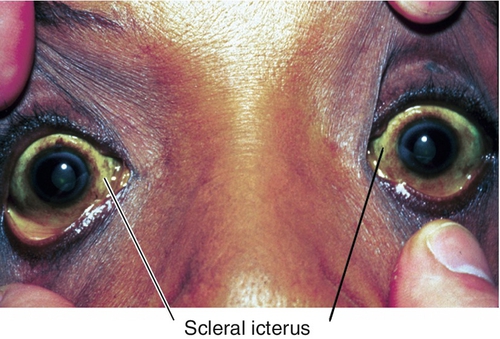

Scleral Icterus

Yellow sclera due to hyperbilirubinemia.

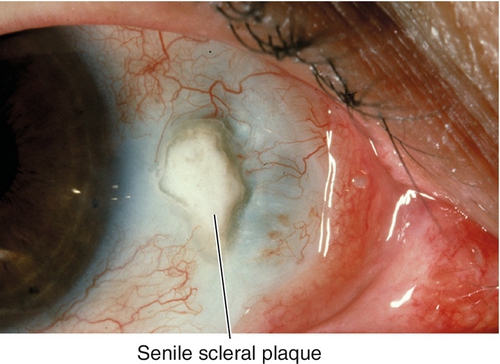

Senile Scleral Plaque

Blue-gray discoloration of sclera located near horizontal rectus muscle insertions due to hyalinization; occurs in elderly patients.

Minocycline

Chronic systemic therapy may cause blue-gray discoloration of sclera that appears as a vertical band near the limbus; possibly due to photosensitization; may also cause pigmentary changes in teeth, hard palate, pinna of ears, nail beds, and skin.

Symptoms

Asymptomatic; may notice scleral discoloration.

Signs

Focal or diffuse discoloration of sclera in one or both eyes.

Differential Diagnosis

See above; also foreign body, melanoma, mascara, intrascleral nerve loop, adrenochrome deposits (epinephrine), scleromalacia perforans.

Evaluation

• B-scan ultrasonography and gonioscopy to rule out suspected extension of uveal melanoma.

• Medical consultation for systemic diseases.

Prognosis

Good; discoloration itself is benign.