Congenital pediatric airway problems

Anesthetic management of the difficult pediatric airway

• The preoperative use of H2-receptor blocking agents may be considered in infants at risk for aspirating.

• Intravenous access should be established either before or as soon as possible after induction.

• The use of intravenously administered sedatives, opioids, or neuromuscular blocking agents should be avoided.

• Atropine should be administered before laryngoscopy is attempted.

• The intravenous administration of lidocaine, 1 mg/kg, before intubation may decrease the risk of laryngeal spasm. Alternatively, topical translaryngeal lidocaine can be given, remembering that transmucosal absorption of lidocaine is close to that of intravenously administered lidocaine.

• Preoxygenation is strongly recommended.

• A variety of laryngoscopy blades, tracheal tubes, and stylets should be readily available.

• Laryngoscopy should be performed under deep anesthesia.

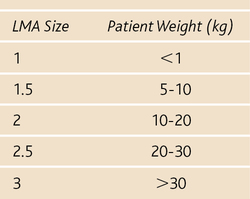

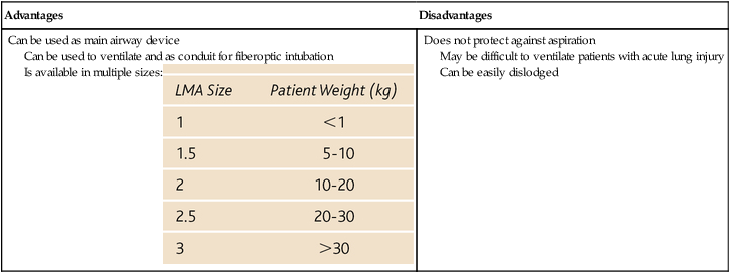

• The use of either mask ventilation or a laryngeal mask airway may be warranted (Box 200-1).

• Several intubation approaches should be considered (e.g., awake, blind nasal, fiberoptic), but alternative methods must be immediately available, including facilities for cricothyrotomy or tracheostomy.

• Induction with sevoflurane via spontaneous ventilation is preferred if awake intubation is not possible. Sevoflurane has a rapid onset of action, provides a smooth induction, and will not sensitize the heart to endogenous catecholamines, such as halothane does (halothane is no longer used in the United States but it may still be used in developing countries by anesthesia providers who provide humanitarian care there to pediatric patients.” Desflurane should not be used for induction because of its pungency and propensity to irritate the airway.

• Spontaneous ventilation should be maintained.

• Fiberoptic intubation is becoming more desirable in pediatric patients as smaller bronchoscopes become available. Currently, pediatric bronchoscopes are available that will fit through a 3.0-mm tracheal tube, although they do not have suction ports.