Congenital diaphragmatic hernia

Congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) most commonly presents as respiratory distress and cyanosis in a baby shortly after birth and is a true surgical emergency. Because the diaphragmatic malformation originates early in fetal development, the presence of intestines in the thorax inhibits lung development, resulting in the primary problem in CDH—hypoplasia of the lung parenchyma and pulmonary vasculature. CDH is often associated with other congenital problems that may affect the management of anesthesia (Table 201-1).

Table 201-1

Congenital Problems Associated with Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

| System | Frequency (% of Affected Neonates) | Associated Problem(s) |

| Central nervous system | 28 | Encephalopathy, hydrocephalus, spina bifida |

| Polyhydramnios, without gastrointestinal anomalies | 30 | |

| Gastrointestinal | 20 | Intestinal atresia, malrotation |

| Genitourinary | 15 | Hypospadias |

| Cardiac | 13-23 | Atrial septal defect, coarctation, tetralogy of Fallot, ventricular septal defect |

Incidence and classification

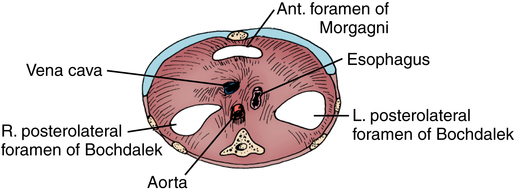

CDH occurs in about 1 in every 2500 live births. Classification is based on location of the defect, with the most common and significant being the posterior lateral aspect of the diaphragm, through the foramen of Bochdalek (80%). Left-sided hernias occur five times more often than right-sided ones. Hernias through the esophageal hiatus are generally small, with no compromise of pulmonary function, and do not usually present in the neonatal period. Figure 201-1 illustrates other sites in which hernias may be evidenced. Incomplete muscularization of the diaphragm (eventration) may occur, resulting in the development of a hernia sac. Many cases are asymptomatic, but severe cases may present identically to CDH.

The use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

Criteria have been established to identify infants with CHD who do not respond to pharmacologic and ventilatory therapy, a group that might benefit from a period of ECMO to provide time for pulmonary growth and remodeling. Selection criteria for ECMO include hemodynamic instability, persistent acidosis, and pneumothoraces, as well as severe pulmonary hypertension unresponsive to pharmacologic intervention. However, the use of ECMO is associated with significant risks, and contraindications do exist (Box 201-1). ECMO is discontinued if irreversible brain damage or lethal organ failure occurs or when lung function improves. The overall survival rate of infants with CDH treated with ECMO is reported to be between 50% and 87%.