Chapter 378 Congenital Anomalies of the Larynx, Trachea, and Bronchi

Because the larynx functions as a breathing passage, a valve to protect the lungs, and the primary organ of communication, symptoms of laryngeal anomalies are those of airway obstruction, difficulty feeding, and abnormalities of phonation (Chapter 365). Obstruction of the pharyngeal airway (due to enlarged tonsils, adenoids, tongue, or syndromes with midface hypoplasia) typically produces worse obstruction during sleep than during waking. Obstruction that is worse when awake is typically laryngeal, tracheal, or bronchial and is exacerbated by exertion. Congenital anomalies of the trachea and bronchi can create serious respiratory difficulties from the first minutes of life. Intrathoracic lesions typically cause expiratory wheezing and stridor, often masquerading as asthma. The expiratory wheezing contrasts to the inspiratory stridor caused by the extrathoracic lesions of congenital laryngeal anomalies, specifically laryngomalacia and bilateral vocal cord paralysis.

378.1 Laryngomalacia

Diagnosis

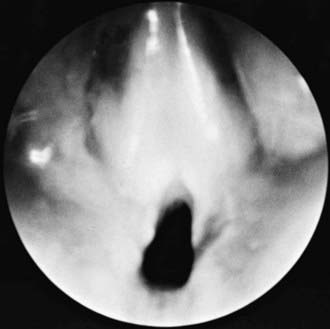

The diagnosis is confirmed by outpatient flexible laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-1). When the work of breathing is moderate to severe, airway films and chest radiographs are indicated. With associated dysphagia, a contrast swallow study and esophagram may be considered. Because 15-60% of infants with laryngomalacia have synchronous airway anomalies, complete bronchoscopy is undertaken for patients with moderate to severe obstruction.

Dickson JM, Richter GT, Derr JM, et al. Secondary airway lesions in infants with laryngomalacia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2009;118:37-43.

Holinger LD, Konior RJ. Surgical management of severe laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:136.

Thompson D. Abnormal integrative function in laryngomalacia. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(6(Pt Suppl 114)):1-33.

378.4 Congenital Laryngeal Webs and Atresia

Most congenital laryngeal webs are glottic with subglottic extension and associated subglottic stenosis. Airway obstruction is not always present and may be related to the subglottic stenosis. Thick webs may be suspected in lateral radiographs of the airway. Diagnosis is made by direct laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-2). Treatment might require only incision or dilation. Webs with associated subglottic stenosis are likely to require cartilage augmentation of the cricoid cartilage (laryngotracheal reconstruction). Laryngeal atresia occurs as a complete glottic web and commonly is associated with tracheal agenesis and tracheoesophageal fistula.

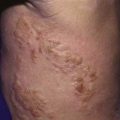

378.5 Congenital Subglottic Hemangioma

Symptoms of airway obstruction typically occur within the 1st 2 mo. of life. Stridor is biphasic but usually more prominent during inspiration. A barking cough, hoarseness, and symptoms of recurrent or persistent croup are typical. A facial hemangioma is not always present, but when it is evident, it is in the beard distribution. Chest and neck radiographs can show the characteristic asymmetric narrowing of the subglottic larynx. Treatment is discussed in Chapter 382.3.

378.6 Laryngoceles and Saccular Cysts

A laryngocele is an abnormal air-filled dilation of the laryngeal saccule. It communicates with the laryngeal lumen and, when intermittently filled with air, causes hoarseness and dyspnea. A saccular cyst (congenital cyst of the larynx) is distinguished from the laryngocele in that its lumen is isolated from the interior of the larynx and it contains mucus, not air. A saccular cyst may be visible on radiography, but the diagnosis is made by laryngoscopy (Fig. 378-3). Needle aspiration of the cyst confirms the diagnosis but rarely provides a cure. Approaches include endoscopic CO2 laser excision, endoscopic extended ventriculotomy, or, traditionally, external excision.

Figure 378-3 Endoscopic photograph of a saccular cyst.

(From Ahmad SM, Soliman AMS: Congenital anomalies of the larynx, Otolaryngol Clin North Am 40:177–191, 2007, Fig 3.)

Civantos FJ, Holinger LD. Laryngoceles and saccular cysts in infants and children. Arch Otolaryn Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:296-300.

Kirse DJ, Rees CJ, Celmer AW, et al. Endoscopic extended ventriculotomy for congenital saccular cysts of the larynx in infants. Arch Otolarygol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(7):724-728.

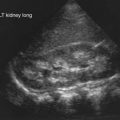

378.8 Vascular and Cardiac Anomalies

The aberrant innominate artery is the most common cause of secondary tracheomalacia (Chapter 426). Expiratory wheezing and cough occur and, rarely, reflex apnea or “dying spells.” Surgical intervention is rarely necessary. Infants are treated expectantly because the problem is self-limited.

The term vascular ring is used to describe vascular anomalies that result from abnormal development of the aortic arch complex. The double aortic arch is the most common complete vascular ring, encircling both the trachea and esophagus, compressing both. With few exceptions, these patients are symptomatic by 3 mo of age. Respiratory symptoms predominate, but dysphagia may be present. The diagnosis is established by barium esophagram that shows a posterior indentation of the esophagus by the vascular ring (Fig. 426-2). CT scan with contrast or MRI with angiography provides the surgeon the information needed (Chapter 426).