209 Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

• Conflict is the result of discordant expectations, goals, needs, agendas, communication styles, and backgrounds between or among individuals. At least two perspectives contribute to conflict.

• Conflict in emergency medicine (EM) may occur with patients, family members, nurses, consultants, residents, students, hospital administrative staff, or agents inside and outside the emergency department.

• The goals of effective conflict resolution are to optimize immediate outcomes and to establish a solid foundation for subsequent interactions. Success depends on one’s communication style, awareness of other’s needs and psyche, and understanding of relationship dynamics.

• Successful conflict resolution requires a systematic and structured approach. Recognizing each participant’s principal interests and underlying positions is important. Having a strong BATNA (best alternative to a negotiated agreement) is beneficial. Possessing a “win-lose” attitude interferes with successful conflict resolution.

• Not all conflict in EM can be resolved immediately, if at all; some resolutions require the assistance of a third party.

• Efforts to prevent conflict before it happens are recommended whenever possible.

Conflict is inevitable. Opportunities for conflict in emergency medicine (EM) are numerous because individuals with different backgrounds and divergent agendas interact over important concerns (e.g., patient care or resource use). By nature, these interactions take place under time constraints, which often exacerbate conflict. Many interactions between emergency physicians (EPs) and patients, family members, staff members, or consultants occur with limited or no previous working relationship or when prior interactions have been problematic. As such, involved parties may be unable to reflect on prior successful interactions, an approach that often decreases the likelihood of intense exchange.2

Communication, in the form of language and interaction, and power, in terms of how conflict is managed (or mismanaged), are tremendously important in the dynamics of groups. EM is very much about group dynamics because physicians, nurses, and other staff members must consistently demonstrate successful teamwork to offer patients the best possible outcomes. Louise B. Andrew, MD, JD, stated “… conflict is often the result of miscommunication, and may be ‘fueled’ by ineffective communication.”3

For additional information about sources and types of conflict, see the online version of this chapter at www.expertconsult.com

Examples of Conflict

Because the specialty of EM is so complex and has tremendous liability associated with its practice environment, many areas of potential conflict have been addressed at federal, state, and local levels. Hospital policies and bylaws have established guidelines addressing these issues, in an attempt to prevent conflict before it occurs. Despite these policies, conflict still occurs. EM organizations are addressing these and other areas of potential conflict, based on the needs of emergency patients and professionals. As health policy and the specialty of EM evolve, new challenges will be identified, with more issues requiring resolution (Box 209.1).

Box 209.1 Areas of Conflict Related to Emergency Medicine

1. Differences in education, background, values, belief systems, and interpersonal styles of communication between EPs and others

2. Commitment to patient satisfaction

3. Final patient disposition (and who determines this)

4. Timing of follow-up care and outpatient tests for released patients

5. Telephone conversations required for patient care issues

6. Lack of professional respect from primary physicians or consultants

7. Dual advocacy expected by others for the EP

8. Teaching hospitals with house staff who may lack communication and conflict resolution skills, have less commitment to the hospital, patients, or ED staff because of temporary scheduling at that hospital or ED, and sense a lack of input, ownership, and control over patients’ (or their own) lives

9. Patient transfers to or from the ED

10. Time limitations and urgency

11. Practice variability, including patient hand-offs

12. High patient acuity and volume

13. Space issues and patient privacy

14. Federal or hospital reporting mandates

15. EM practice, such as caring for multiple patients with limited information, with risk of great morbidity and mortality

16. Threat of litigation related to high stakes, clinical challenges, and patient’s lack of previous personal relationship with EPs

ED, Emergency department; EM, emergency medicine; EP, emergency physician.

Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

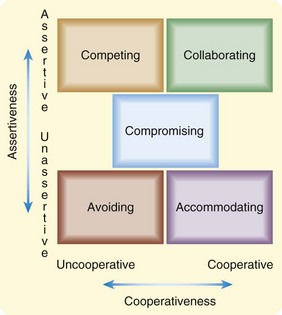

Conflict resolution for today’s interactions is crucial to tomorrow’s triumphs because future conflict is inevitable. Individuals likely adapted their approach to conflict management based on what “worked” for them in childhood, or from observing mentors. Conflict itself is not necessarily problematic, but how individuals (or organizations) deal with it may be. Five distinct responses to conflict can be plotted using the axes of assertiveness (the extent that individuals attempt to satisfy their own concerns) and cooperativeness (the extent that individuals attempt to satisfy the concerns of others) (Fig. 209.1). Each of these responses to conflict or approaches to resolving it has advantages and disadvantages and circumstances when it may prove effective or ineffective. For example, an EP preferring the accommodating style (low assertiveness and high cooperativeness) may have poor patient outcomes over time. The competing style employed by many EPs may create quick results necessary for patient care, but it is unpopular.

Strategies for Successful Conflict Resolution

With all this conflict occurring in the ED, successful EPs apply strategies to reduce or resolve it, to preserve the best possible patient and provider satisfaction without compromising patient care. Drs. Marco and Smith described 10 reasonable principles for conflict resolution in EM (Box 209.2).4 EPs should make it their “standard of care” to refrain from hostile communication and instead persuade others using kindness and intellect, focusing on patient advocacy and safety.

Box 209.2

Principles of Conflict Resolution in Emergency Medicine

1. Establish common goals (e.g., to deliver the best or most appropriate patient care possible in a patient-centered fashion).

3. Do not take conflict personally.

4. Avoid accusations and public confrontations.

6. Establish specific commitments and expectations (e.g., Who will see the patient? At what time? Who will assume responsibility for care, including admission or discharge orders and/or instructions?).

7. Accept differences of opinion.

8. Use ongoing communications (invest in future interactions).

9. Consider a neutral mediator for situations that are not working and become disruptive or emotionally problematic.

Data from Marco CA, Smith CA. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med 2002;40:347–9.

O’Mara focused on the interrelationship between communication and conflict resolution. She wrote that “each relationship presents its own potential for ongoing communication dynamics, which may include conflict and misunderstanding” and added that “appreciating alternative viewpoints and a willingness to adapt are prerequisites for managing interpersonal conflict.”5

Relationships in the Emergency Department

The book Getting to Yes describes using principled negotiation, which decides issues on their merit to resolve conflict, rather than through a haggling process focused on what each side says it will and will not do.6 This method suggests looking for mutual gains whenever possible. When interests conflict, individuals should insist that the result of negotiation be based on fair standards, independent of the will of the other side.

Getting to Yes recommends that negotiators develop their best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA), which serves as the basis for exploring and evaluating options.6 This approach involves thinking carefully about what would happen if a negotiated agreement cannot be reached, while simultaneously serving as an impetus to engage in a process with agreement as the outcome. Communication that begins with careful, empathic listening helps resolve conflict and allows the other party to feel heard. Avoiding negative comments or ridicule (especially public) and depersonalizing the conflict are healthy approaches to its management. This allows the other party to maintain self-esteem and self-respect. Remaining objective and maintaining composure while focusing on the issues are important. One must be careful when responding to emotions; silence can be powerful and may de-escalate conflict.7

Benefits of Conflict Resolution

Dr. Andrew recommended “paraphrasing the communication back to the complainer” and “expressing a willingness to find a common ground.”3 These recommendations are critical because conflict is often generated (and many times escalated) by the fear that a concern was not heard or validated. Dr. Andrew described four A’s that assist with conflict resolution:

1. Acknowledge the conflict (“I understand your concern. I can tell you are not pleased with what has taken place.”).

2. Apologize (blamelessly) for the situation (“I’m sorry this situation occurred.”).

3. Actively listen to the concern (“Please go on. I want to hear more about this.”).

4. Act to amend (“I promise I will act to fix this situation and [try] to make certain it doesn’t happen again to someone else.”).3

Skillful negotiating techniques embody an empowering, active, constructive, and positive approach to resolving difficulties and often yield successful outcomes or incremental change over time. Numerous benefits result from successful conflict resolution, with short- and long-term impact (Box 209.3).

Box 209.3 Positive Outcomes of Conflict Resolution

1. Improved communication with patients and colleagues

2. Reduced stress levels and improved staff morale

3. Increased workplace productivity (and possibly reimbursement), with reduced expenditures related to conflict

4. Promotion of healthy relationships with colleagues and staff

5. Improved patient, staff, and physician satisfaction

6. Decreased staff turnover (increased staff retention)

8. Prevention of future conflict, or at least resolution of future conflict more effectively and expeditiously

Summary

Conflict has been described as a natural consequence of incompatible behaviors and unmet expectations.7 The preferred strategy to manage conflict is to prevent its occurrence, which is not easy in EM. Effective communication among individuals and within groups in which parties are respected and heard produces an environment of trust. This results in the likelihood that conflict will be resolved more effectively. EPs should be aware of their behaviors and styles of interaction that increase conflict in an environment predisposed to conflict. Furthermore, EPs must strive to understand principles of conflict and conflict resolution, including effective communication, strong interpersonal and listening skills, and the tenets of professionalism because they may help achieve successful EM practices (Box 209.4).

Box 209.4 Comprehensive Approach to Successful Conflict Resolution

1. Accept the existence of the conflict.

3. Separate the person from the problem.

4. Clarify and identify the nature of the problem creating conflict.

5. Deal with one problem at a time, beginning with the easiest.

6. Engage the respective parties in an environment of impartiality.

7. Listen with understanding and interest, rather than evaluation.

8. Validate issues and concerns.

9. Identify areas of agreement; focus on common interests, not on positions.

10. Attack data, facts, assumptions, and conclusions, but not individuals.

11. Brainstorm realistic solutions in which both parties benefit.

12. Use and establish objective criteria, when possible.

13. Do not prolong or delay the process.

15. Evaluate and assess the problem-solving process after implementing the plan (follow up periodically).

1 Ahuja J, Marshall P. Conflict in the emergency department: retreat in order to advance. Can J Emerg Med. 2003;5:429–433.

2 Garmel GM. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. In: Adams JG, Barton ED, Collings J, et al. Emergency medicine. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2008.

3 Andrew LB. Communication, conflict resolution, and negotiation. Bintliff SS, Kaplan JA, Meredith JM. Wellness book for emergency physicians. Dallas: American College of Emergency Physicians; 2004:48–50. http://www.acep.org/Content.aspx?id=32184&terms=Wellness.

4 Marco CA, Smith CA. Conflict resolution in emergency medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;40:347–349.

5 O’Mara K. Communication and conflict resolution. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1999;17:451–459.

6 Fisher R, Ury W, Patton B. Getting to yes: negotiating agreement without giving in, 2nd ed. New York: Penguin Books; 1991.

7 Strauss RW, Halterman MK, Garmel GM. Conflict Management. In: Strauss and Mayer’s Emergency Department Management. New York: McGraw-Hill, in press.