Chapter 40 Complications of Assisted Reproductive Technologies

OVARIAN HYPERSTIMULATION SYNDROME

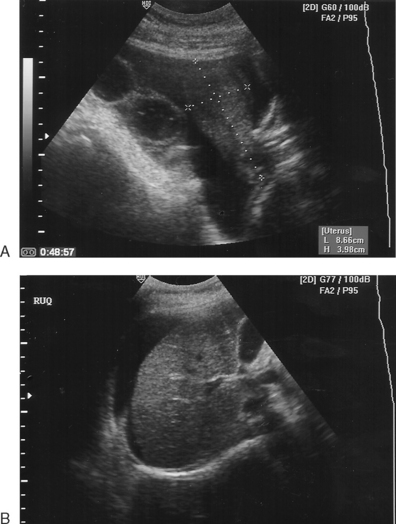

OHSS is the most common and potentially serious complication of ovarian hyperstimulation for ART procedures, especially in vitro fertilization (IVF). This syndrome consists of ovarian enlargement in conjunction with a continuum of symptoms, depending on severity (Fig. 40-1). In the mildest cases, the patient experiences only pelvic discomfort and nausea. More serious cases are associated with vomiting, abdominal distension, and ascites. The most severe cases can result in respiratory distress, oliguria, hemoconcentration, and thrombosis. In rare cases, death has been reported.

Incidence

The vast majority of OHSS cases occur in association with ovarian stimulation with injectable gonadotropins. Only occasional cases have been observed after clomiphene citrate administration, and very rare cases have been reported during the first trimester of pregnancy resulting from spontaneous unstimulated ovulation.1,2 Sporadically reported cases of familial spontaneous OHSS may be due to a mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor, leading to hypersensitivity of the corpus luteum to human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG).3,4 However, the great majority of cases develop after use of injectable gonadotropins for ovarian hyperstimulation before in vitro fertilization (IVF).

The actual frequency of OHSS varies depending on patient factors, surveillance methods, and management approaches. Mild cases occur in as many as 30% or more of patients undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation with gonadotropins for IVF and often go unrecognized due to the benign nature of the signs and symptoms.5 In general, less than 5% of patients undergoing IVF would be expected to develop moderate symptoms and less than 1% will develop severe symptoms.6,7 It remains unclear why many high-risk induction cycles do not result in severe OHSS while others do.

Pathogenesis

OHSS is the result of excessive follicular response during the follicular phase, but manifests exclusively during the luteal phase following a surge in luteinizing hormone (LH) or ovulatory dose of hCG. The severity and duration is intensified by additional doses of exogenous hCG for luteal support and rising levels of endogenous hCG if the patient becomes pregnant.1,5,8

Vasoactive Substances

Possible participants in the pathogenesis of OHSS include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), prostaglandins, other members of the cytokine family, and nitric oxide, as well as components of the renin and the angiotensin system, especially angiotensin II.9–13 All of these are recognized participants in the normal physiology of folliculogenesis and luteogenesis.14,15

The primary mediator of increased vascular permeability associated with OHSS appears to be the cytokine VEGF.9,10 VEGF is secreted by granulosa and theca cells in the late follicular phase. Neoangiogenesis, essential to folliculogenesis and especially to luteogenesis, is induced largely by VEGF.11–13

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is most commonly thought to be the result of vascular hyperpermeability caused by excessive VEGF-induced changes associated with extreme neoangiogenesis. The expression of VEGF by granulosa cells has been shown to be up-regulated by hCG, and unbound levels of VEGF correlate with the severity of OHSS.16,17 Inhibition of VEGF is associated with improvement in vascular permeability.18,19 Evidence indicates that supernumerary follicles are the predominant source of superphysiologic quantities of VEGF in patients who develop OHSS.20 VEGF acting directly or indirectly in concert with other factors may diffuse into the peritoneal cavity, resulting in increased permeability of diffuse mesothelial vessels. Removal of these substances by paracentesis may facilitate reduction of capillary hyperpermeability, resulting in the observed improvement in the clinical sequelae.21

Fluid Homeostasis

The hemoconcentration associated with OHSS leads to hypercoagulability and increased risk of thromboembolism, especially if it occurs in combination with thrombophilias or other coagulopathies.22,23 There is also evidence that OHSS may induce a primary hypercoagulable state independent of hemoconcentration.24

The hypovolemia resulting from OHSS can lead to low blood pressure and decreased central venous pressure, followed by decreased renal perfusion. Decreased renal perfusion results in increased sodium and water reabsorption in the proximal tubule and reduced exchange of hydrogen and potassium for sodium in the distal tubule, potentially leading to oliguria with prerenal azotemia, hyponatremia, and hyperkalemic acidosis.25 Medical complications secondary to OHSS include renal insufficiency, adult respiratory distress syndrome, hepatocellular damage, hypovolemic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and thromboembolism.5

Risk Factors

No single clinical characteristic or combination of characteristics is 100% predictive of OHSS. However, the incidence is increased by any factor that increases ovarian response (Table 40-1). Patients at highest risk for severe OHSS are those who meet the folowing criteria:

Table 40-1 Risk Factors for Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome (OHSS)

| Younger age |

| Low body mass index |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome |

For patients with both of these risk factors, the incidence of severe OHSS has been reported to be as high as 80%.26

The occurrence of OHSS is more closely correlated with degree of ovarian stimulation than it is with the dose and duration of gonadotropins.27–29 OHSS occurs more commonly in women with ovaries that are highly sensitive to FSH stimulation, specifically young women and women with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).28,30 Higher doses of gonadotropin are also associated with an increased incidence of OHSS, but only to the extent that higher doses result in more vigorous ovarian stimulation.29 The presence of a large number of follicles, particularly small and moderate-sized follicles, at the time of initial hCG is a positive risk factor for OHSS.2 Estrogen produced by the developing follicles serves as a marker of the degree of ovarian hyperstimulation. High estrogen levels in excess of 4000 pg/mL are of particular concern in the presence of numerous small to medium-sized follicles in contrast to a smaller number of exclusively large or mature follicles.1,28,31

Clinical Symptoms

Classification

OHSS is best thought of as a broad continuum of signs and symptoms.27,28 However, for management and reporting purposes, OHSS is generally classified as mild, moderate, or severe (Table 40-2). Mild OHSS is a self-limited and clinically benign condition characterized by ovarian enlargement (generally less than 5 cm), abdominal bloating, and discomfort. Moderate OHSS indicates progressively greater ovarian enlargement and significant symptoms that are difficult to manage outside a hospital environment. Severe OHSS involves massive cystic ovarian enlargement in excess of 10 cm and tense abdominal ascites with or without pleural effusion.27

Table 40-2 Classification of Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome

Modified from Navot D, Bergh PA, Laufer N: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in novel reproductive technologies: Prevention and treatment. Fertil Steril 58:249–261, 1992.

Onset of Symptoms

Most commonly, patients present with complaints of abdominal bloating, shortness of breath, nausea, unusual weight gain, and decreased urine output. Patients with severe OHSS appear ill, with marked abdominal distension secondary to ascites. They frequently become significantly short of breath in the supine position, again secondary to abdominal ascites. Laboratory findings include elevated hematocrit, leukocytosis, hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN)-to-creatinine ratio, and occasionally mildly elevated results on liver function tests. On ultrasound, ovaries will be large and cystic with variable amounts of free peritoneal fluid filling the abdominal space. Occasional patients will present with a pleural effusion, most commonly right sided, with or without abdominal ascites.29

Prevention

Avoidance of Excessive Stimulation

If rapidly rising estrogen levels reach or threaten to become unacceptably high, withholding the daily dose of gonadotropin can reduce the incidence and severity of OHSS. This approach, coasting, can in some cases result in arrest and atresia of all or most of the follicles; however, in many cases hCG administration can be delayed until the estradiol level returns to a more acceptable level without a detrimental effect on the subsequent oocyte and embryo quality or pregnancy rate.33–36 Coasting has been shown to be associated with reduced concentrations of follicular VEGF and a significantly lower incidence of severe OHSS.37 Coasting is most successful when the serum estradiol has exceeded 3000 pg/mL and the lead follicle has reached a diameter larger than 14 mm. If growth of the lead follicles continues, administration of hCG can be withheld for up to 4 days until the serum estradiol reaches an acceptable level. Prolonged coasting beyond 4 days is associated with a decrease in implantation and pregnancy rates.38

Withholding hCG

Because the clinical signs and symptoms of hyperstimulation will not develop until final follicular maturation and luteinization occur in response to hCG or LH, it is most prudent to withhold the ovulatory dose of hCG in patients who are clearly overstimulated based on follicular number, size, and estrogen level.31,33 Although the decision to drop a cycle ultimately becomes a matter of clinical judgment, in general it is our practice to withhold hCG in the presence of a large number of small follicles and a peak estradiol level in excess of 4000 pg/mL.

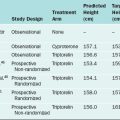

Intravenous Albumin

Intravenous administration of an osmotically active “colloid” agent at the time of retrieval appears to reduce the risk and severity of OHSS in high-risk patients. Administration of intravenous albumin (25 g) during and immediately after the egg retrieval has been recommended for women with a peak estradiol level of 3000 pg/mL or a large number of small and intermediate-sized follicles.39 Based on a meta-analysis using the Cochrane standard, it is estimated that for every 18 women treated with albumin, 1 case of OHSS will be avoided.40 However, prophylactic administration of albumin to high-risk patients remains controversial because of conflicting data regarding its efficacy as well as concerns regarding the expense and safety.41

The mechanism of action for intravenous albumin is not clear. It was initially hypothesized that albumin exerts it effect by increasing intravascular osmotic pressure. However, because of its small molecular weight, albumin is cleared from the circulation within a short time of the retrieval. Other possible mechanisms include increased plasma binding of a factor or factors involved in the pathogenesis of OHSS. Other osmotic agents have also been used with some success, including 5% hydroxyethylstarch and 3.5% degraded gelatin polypeptides (Haemaccel).42–44

Luteal Phase Support

Introduction of a GnRH antagonist early in the luteal phase will lead to early luteolysis.45 Because OHSS resolves with involution of the corpora lutea, the clinical course of severe OHSS can be abbreviated or even eliminated by this approach. If the stimulation protocol did not include down-regulation with a GnRH agonist, the gonadotropin flare secondary to initiation of a GnRH agonist can be used to induce oocyte maturation and ovulation followed almost immediately by irreversible luteolysis.18,46–51

Pituitary response to initiation of a GnRH agonist is preserved following a GnRH antagonist/gonadotropin stimulation protocol. If embryos are transferred in a cycle in which premature luteolysis is induced, exogenous hormone replacement is required to support endometrial maturation and implantation.52 Alternatively, the embryos can be cryopreserved for transfer at a later time.53

Management of OHSS

Diagnosis

Proactive management of patients with early signs and symptoms of OHSS can ameliorate the severity of OHSS.54 Patients generally present with complaints of abdominal bloating, shortness of breath, and nausea. Symptomatic patients should be seen and evaluated promptly. Clinical parameters should include a physical examination, including a chest and abdominal examination (but not a bimanual pelvic examination) as well as a pelvic or abdominal ultrasound for ovarian enlargement or ascitic fluid and to rule out torsion.

Laboratory studies should include complete blood count, electrolytes, BUN, and creatinine. Hemoconcentration (hematocrit >45%) heralds the development of ascites, marginal renal perfusion, and decreasing urine output and increases the risk of thromboembolic events.55

Most patients with OHSS will have some degree of ascites (Table 40-3). Less commonly, patients will develop pleural effusion, which can occur unilaterally (usually on the right) and in the absence of significant abdominal ascites. A high index of suspicion and careful evaluation are important to differentiate this condition from pulmonary embolism.32

| Ascites |

Treatment

Active management of OHSS early in the onset of the signs and symptoms of the syndrome can avoid hospitalization and minimize the progression and complications of OHSS.54 Patients at risk should be instructed to monitor fluid intake, urine output, and daily weights (Table 40-4). Oral fluid replacement is encouraged with electrolyte-containing liquids such as sports drinks.

Table 40-4 General Principles of Management of a Hospitalized Patient with OHSS

| Daily physical examination, avoiding a pelvic examination |

| Monitor vital signs, including oxygen saturation (pulse oximeter) |

| Monitor urine output closely |

| Daily checks of weight and abdominal girths |

| Daily hematocrit/hemoglobin, white blood cell count, liver enzymes, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine testing |

| Aggressive intravenous normal saline or colloids to maintain adequate urine output and to treat the hemoconcentration |

| Subcutaneous prophylactic anticoagulation |

| Paracentesis or thoracocentesis, if necessary |

Adapted from Avecillas JF, Falcone T, Arroliga AC: Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Criti Care Clin 20:679–695, 2004.

Intravenous fluid and electrolyte management can often be managed in the outpatient setting. Patients presenting with evidence of hemoconcentration manifested by rising hematocrit well above baseline, particularly approaching 50%, with leukocytosis, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, or reduced urine output require intravenous fluid replacement with crystalloid.8

Abdominal paracentesis can be safely performed under ultrasound guidance either abdominally or transvaginally in patients with significant ascites.55 Patients presenting with significant hemoconcentration but without significant ascites should be monitored closely for accumulation of extravascular fluid after hydration. Paracentesis is expected to significantly improve urine output and hemoconcentration, possibly by reducing intra-abdominal pressure compressing the vena cava.8,56,57 Osmotically active volume expanders, most commonly albumin, used in combination with intravenous crystalloids and paracentesis, can also be used reduce hemoconcentration and maintain vascular volume.43,54,58 Anticoagulants should be considered if hemoconcentration does not respond to IV fluids and volume expanders or if the patient has a concomitant hypercoagulability, such as Factor V Leiden deficiency.

Hospitalization is necessary for any patient who cannot be comfortably managed as an outpatient or who develops significant medical complications.59 Rare complications of severe OHSS include vascular collapse, adult respiratory distress syndrome, renal failure, and venous thrombosis. For the patient with the most extreme presentation of severe OHSS, adequate support may require in addition to the above, placement of a central line and administration of pressors (see Table 40-3).

As a last resort for management of these extreme cases, surgical destruction of the corpora lutea or pregnancy termination has been advocated.60 With aggressive proactive and active management of high-risk patients, these measures should have a very limited place in clinical management of OHSS.6 However, surgical intervention may be required for ovarian cysts associated with OHSS if they undergo torsion, hemorrhage, or rupture.

MULTIPLE PREGNANCIES

Many couples do not appear to be appropriately concerned regarding multiple pregnancies, either as a result of the intense desire to achieve pregnancy or the lack of knowledge regarding the morbidity associated with multiple pregnancies. A survey of 77 women embarking on either gonadotropin or IVF therapy showed that 95% of women preferred getting pregnant with triplets to not getting pregnant and 68% of women preferred getting pregnant with quadruplets to not getting pregnant.61 Another report on patient preference showed that more than 20% of women embarking on infertility treatment preferred multiple pregnancies to a singleton pregnancy.62 Very significantly, 4% of those favoring multiple pregnancies ranked quadruplets as their most desired outcome. Based on these observations, it is not surprising that couples undergoing IVF are often very aggressive regarding the number of embryos to transfer.

Further exacerbating this trend is the pressure on IVF programs to report high success rates to stay competitive. Although there is an increasing emphasis on the undesirability of multiple pregnancies with IVF, success of IVF programs still is undoubtedly judged predominantly by the “take home baby rate,” which does not take into consideration the significant financial costs and morbidity of multiple pregnancies (Fig. 40-2).

Scope of the Problem of Multiple Pregnancies with ART

The number of multiple pregnancies in the United States has increased greatly since 1980. Although a small part of the increase in multiple pregnancy rates is due to other factors, such as increased maternal age, the vast portion is due to infertility treatments. From 1980 to 1999, the multiple pregnancy rates increased approximately 60%, from 1.9% to 3.1% of all births. Numerically most of these represented twin pregnancies. However, the risk of higher-order pregnancies increased from 37 to 193 per 100,000 births, or by more than 400%.63

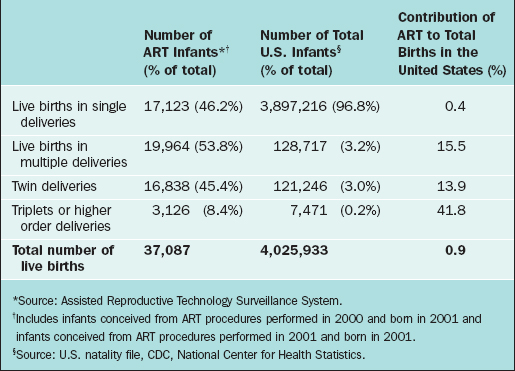

The impact of fertility treatments, and particularly ART, on higher-order pregnancies is momentous. Although ART is responsible for only 0.4% of all live births, this technology is responsible for 13.9% of twin births and 41.8% of higher-order deliveries (Table 40-5).64 Higher-order multiples are associated with a large number of medical problems.65–70

Table 40-5 Effect of Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) on Total Births by Plurality—United States 2001

The application of ART treatments appears to increase the risk of both dizygotic and monozygotic twins and of higher-order deliveries. Ovulation induction increases the incidence of monozygotic twinning to 1.2% compared to the 0.4% incidence in the general population.71,72 IVF increases the risk of monozygotic twinning even further, especially when embryos are transferred at the blastocyst stage. Monozygotic twinning occurs in 5.6% of IVF pregnancies conceived after blastocyst transfer compared to 2% after cleavage-stage transfer.74 In addition, the presence of more than one gestational sac also increases the risk of monozygotic twinning.75–77

Problems Associated with Multiple Pregnancies

Prematurity

Clearly, the major cause of morbidity with multiple pregnancies is prematurity. Fully one third of triplets and two thirds of quadruplets will be born at less (and often considerably less) than 32 weeks’ gestation.66 Approximately 25% of twins and 75% of triplets will be admitted to a neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The average number of days these infants will spend in a NICU is 18 days for twins, 30 days for triplets, and 58 days for quadruplets.67

Small for Gestational Age

In addition to prematurity, multiple gestations are also at increased risk for small for gestational age (SGA) babies, the rate of which increases with gestational age. For twins, 28% will be SGA by 34 weeks’ gestation, and this rate will climb to 40% by 37 weeks’ gestation.67 For triplets, 50% will be SGA by 35 weeks’ gestation.

Cerebral Palsy and Other Handicaps

Of all the sequelae of multiple gestations, cerebral palsy is perhaps the most disturbing. Apparently as a result of both prematurity and SGA, the rate of cerebral palsy for twins is increased 5.5-fold, and for triplets the risk is increased almost 20-fold.68,69

Other handicaps are also clearly increased by multiple gestations. In twins, overall handicaps are increased by 39% and severe handicaps are increased by 30%.70 In triplets overall handicaps are increased by 97% and severe handicaps are increased by 71%.

Birth defects are increased by multiple gestations. Monozygotic twins are twice as likely as dizygotic twins to be born with congenital malformations. In one study, the risk of significant congenital anomalies among triples was 5%.69

Infant Mortality

Infant mortality is greatly increased by multiple gestations. The perinatal mortality rate for triplets, including all intrauterine demises and deliveries occurring after 20 weeks’ gestation, is greater than 10% in many studies.69

Infant deaths (under age 1 year) are not as commonly discussed as a sequelae of multiple gestations. Using U.S. vital statistics, it has been shown that, compared to singletons, the number of infant deaths for twins are increased sixfold and for triplets 17-fold.70

Maternal Complications

Essentially all maternal complications of pregnancy are increased by the occurrence of multiple gestations. In addition to preterm labor, this includes preterm premature rupture of membranes, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, anemia, postpartum hemorrhage, and even the relatively rare acute fatty liver of pregnancy.69

Financial Costs

The financial costs of multiple pregnancies are also tremendous. An evaluation of births at a Boston hospital from 1986 to 1991 found that added costs of multiple pregnancies were approximately $38,000 and $110,000 for twins and higher-order multiple pregnancies, respectively.77 Goldfarb and colleagues78 estimated the added cost (above normal costs for a singleton delivery) per woman delivered of pregnancies from an IVF program during the years 1991 and 1992. Estimated added costs included the cost of the IVF procedure, admissions for premature labor, time off from work, and costs for ongoing care of premature infants. The authors found that the added cost per delivery of IVF patients was approximately $39,000 for singleton and twin deliveries versus approximately $343,000 for triplet and quadruplet pregnancies.

Parenting Issues

The psychological impact of raising infants born of multiple gestations cannot be underappreciated. An evaluation of parents of IVF twins reported that these couples found parenting to not be as satisfying as they expected.79 Furthermore, parents of IVF twins seem to be more stressed than parents of naturally conceived twins.

Steps to Minimize the Problem of ART-Associated Multiple Pregnancies

Number of Embryos to Transfer after IVF

Legislation in some European countries strictly limits embryo transfers to two embryos for most patients. In the United States, embryo transfer policy remains controversial because of the issues of parents’ rights to decide on the number of embryos and tradeoffs between higher pregnancy rates and higher multiple pregnancy rates. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) has established guidelines for the number of embryos to transfer in an IVF cycle, the most recent of which was published in 2004.80 These guidelines recommend the transfer of two embryos for patients under age 35 in the absence of “extraordinary circumstances.” Many are strongly advocating stricter guidelines because of the feeling that the goal of ART should only be a healthy singleton birth.81

For many patients, very good success rates can be achieved by transferring a single embryo at the blastocyst stage.82 In view of this, the 2004 ASRM guidelines state that “for patients with the most favorable prognosis, consideration should be given to transferring only a single embryo.”80 Of course, transfer of a single embryo, particularly at the blastocyst stage, does not eliminate the risk of multiple pregnancies.

Insurance coverage appears to influence the number of embryos transferred. A lower incidence of transfer of three or more embryos was found in insured versus noninsured states.83 However, the overall effect of insurance coverage on multiple pregnancies was modest. It has been hypothesized that a substantial effect on multiple pregnancies will occur only if insurance coverage is combined with mandated limits on the number of embryos transferred after IVF.84

NEONATAL RISKS NOT RELATED TO MULTIPLE BIRTHS

Singleton births after IVF, compared to naturally conceived singletons, have an increased risk of congenital anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, and preterm delivery. In several studies, the risk of major congenital anomalies was increased in singletons. It is uncertain whether this is due to the IVF techniques or the underlying infertility problem. A meta-analysis showed pooled odds ratio of 1.31 (95% CI, 1.17–1.45).85 This implies a 30% to 40% increase in risk of congenital anomalies. Because the overall risk of congenital anomalies is 1% to 3%, this suggests an increased risk after IVF of 1.3% to 3.9%. Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) may be associated with a higher risk of sex and autosomal chromosomal anomalies.86

COMPLICATIONS OF TRANSVAGINAL ULTRASOUND-DIRECTED FOLLICULAR ASPIRATION

Bleeding

It is not unusual to observe bleeding from the vaginal vault puncture site at routine inspection at the end of the oocyte retrieval. Vaginal hemorrhage occurs in 8.6% of cases (229 out of 2670 patients).87 Vaginal hemorrhage with a loss of more than 100 mL of blood occurs in 0.8%. This usually responds to the application of firm pressure for a few minutes with no adverse postoperative sequelae.

Severe intra-abdominal bleeding is reported in less than 0.1% of cases.88 Hemorrhage significant enough to cause hemoperitoneum can result from follicle puncture, from the ovarian vessels, or from a punctured iliac vessel. Massive retroperitoneal hematoma requiring an emergency laparotomy can occur from bleeding from the sacral vein.

Pelvic Infections

Vaginal retrieval carries a risk of pelvic infection of less than 1%. Infections can take the form of postoperative pelvic infections or pelvic abscesses that can require surgical drainage in some cases.87,88

The time from oocyte retrieval to the manifestation of a pelvic abscess can be relatively long. Although the diagnosis will be made within 3 weeks after oocyte retrieval in most cases, an interval of 56 days has been reported.87 There has been a report of a rupture of bilateral ovarian abscesses occurring at the end of the second trimester in a twin pregnancy achieved after oocyte retrieval for IVF.89

The cause of pelvic infection after oocyte retrieval is believed to be direct inoculation of vaginal microorganisms. Anaerobic opportunists of the vagina are found to be etiologic agents in pelvic abscesses after transvaginal oocyte retrieval, including Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, Enterococcus, and Peptococcus.87,88 Prophylactic antibiotics should be considered before oocyte retrieval, especially in high-risk patients, such as those with a history of salpingitis, endometriosis, pelvic adhesions, hydrosalpinx, or pelvic surgery. Although there is currently no consensus as to the best antibiotics to use, an animal study suggested that ampicillin or doxycycline might be superior to cefazolin.91

Vaginal disinfection with a 1% solution of povidone-iodine seems attractive, but a study showed that the pregnancy rate was significantly lower in the group after disinfection by povidone-iodine compared to the normal saline washing group.91

Other Complications

Other potentially life-threatening complications are extremely rare after ultrasound-directed ovum retrieval. There has been a report of a bilateral infection of endometriotic cysts after oocyte aspiration and another of acute abdomen due to accidental puncture of a dermoid cyst during oocyte aspiration.92,93 It may be wise to avoid aspiration of sono-opaque cysts during oocyte retrieval. If sebaceous material is unexpectedly obtained during retrieval, copious rinsing of the presumed dermoid cyst might decrease the risk of postaspiration peritonitis from leaking material.

One case of vertebral osteomyelitis caused by E. coli was reported.94 The patient presented with severe low back pain 1 week after ovum retrieval. Other potential complications are trauma to related pelvic structures, including bowel, ureters, and bladder.

Ovarian Cancer and Fertility Drugs: A False Alarm?

Ovarian cancer is diagnosed in approximately 24,000 women in the United States every year. The association of infertility, use of infertility drugs, and ovarian cancer has generated much debate.95–109 Although it is not the most common gynecologic malignancy, it is the most deadly, and approximately half of women with ovarian cancer will die of their disease.110 It is believed that limiting the number of ovulatory cycles decreases the risk of ovarian cancer, because multiparity and long-term use of oral contraceptives decrease this risk. Based on this known association, it was hypothesized that the converse might also be true: inducing multiple ovulations with fertility drugs might increase ovarian cancer risk.98

Several small, retrospective studies in the early 1990s appeared to show an association between fertility drugs and ovarian cancer.95,99–101 A study by Whittemore generated much interest and concern when it suggested that fertility drug use might be associated with a 2.8 relative risk of ovarian cancer.95,97

Several larger studies and meta-analyses were subsequently published that were unable to find an increased risk of ovarian cancer associated with fertility drug use.103–108 More than one of these studies reported the diagnosis of an unusual number of ovarian cancers within the first year after starting IVF, apparently due to the close ultrasound monitoring used.105,106 A meta-analysis of 10 studies suggested that women with infertility are more likely to develop ovarian cancer whether they used fertility drugs or not.107 This might suggest that underlying defects that result in infertility might also increase ovarian cancer risk.

Fortunately, the weight of evidence strongly indicates that there is no causal link between fertility drugs and ovarian cancer. Based on this information, the Practice Committee of the ASRM recommends that infertility patients be counseled that no causal relationship has been established between ovulation-inducing drugs and ovarian cancer.108

1 Blankstein J, Shalev J, Saadon T, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome prediction by number and size of preovulatory ovarian follicles. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:597.

2 Pride SM, Jame CSJ, Yuen BH. The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Semin Reprod Endocrinol. 1990;62:554.

3 Kaiser U. The pathogenesis of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. NEJM. 2003;349:729.

4 Smits C, Olatunbosun O, Delbaere A, et al. Hyperstimulation syndrome resulting from a mutation in the follicle-stimulating hormone receptor. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2004;59:38.

5 Schenker JG, Weinstein D. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A current survey. Fertil Steril. 1978;30:255.

6 Navot D, Bergh PG, Laufer N. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in novel reproductive technologies: Prevention and treatment. Fertil Steril. 1992;58:249.

7 Hugues JN. Ovarian stimulation for assisted reproductive technologies. In: Vayena E, Rowe PJ, Griffin PD, editors. Current Practices and Controversies in Assisted Reproduction. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002.

8 Borenstein R, Elhalah U, Lunenfeld B, et al. Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A re-evaluated therapeutic approach. Fertil Steril. 1989;51:791.

9 McClure N, Healy DL, Rogers PA, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor as capillary permeability agent in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Lancet. 1994;344:235.

10 Ratcliffe EK, Anthony FW, Richardson MC, et al. Morphology and functional characteristics of human ovarian microvascular endothelium. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:1549.

11 Dvorak HF, Brown LF, Detmar M, et al. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor, microvascular hyperpermeability, and angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:1029.

12 Ferrara N, Chen H, Davis-Smyth T, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor is essential for corpus luteum angiogenesis. Nat Med. 1998;4:336.

13 Folkman J, Klagsbrun M. Angiogenic factors. Science. 1987;235:442.

14 Kamat B, Brown L, Manseau E, et al. Expression of vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor by human granulose and theca lutein cells. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:157.

15 Manau D, Arroyo V, Jimenez W, et al. Chronology of hemodynamic changes in asymptomatic in vitro fertilization patients and relationship with ovarian steroids and cytokines. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1178.

16 Wang T, Horng S, Chang C, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin-induced ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome is associated with up-regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:3300.

17 McElhinney B, Ardill J, Caldwell C, et al. Preventing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by inhibiting the effects of vascular endothelial growth factor. J Reprod Med. 2003;48:243.

18 Emperaire JC, Ruffie A. Triggering ovulation with endogenous luteinizing hormone may prevent the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:506.

19 Abramov Y, Barak V, Nisman B, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor plasma levels correlate to the clinical picture in ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:261.

20 McElhinney B, Ardill J, Caldwell C, et al. Variations in serum vascular endothelial growth factor binding profiles and the development of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;78:286.

21 Revel A, Barak V, Lavy Y, et al. Characterization of intraperitoneal cytokines and nitrites in women with severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:66.

22 Fabregues F, Tassies D, Reverter JC, et al. Prevalence of thrombophilia in women with severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome and cost-effectiveness of screening. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:989.

23 Horstkamp B, Lubke M, Kentenich H, et al. Internal jugular vein thrombosis caused by resistance to activated protein C as a complication of ovarian hyperstimulation after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:280.

24 Rogolino A, Coccia ME, Gedi S, et al. Hypercoagulability, high tissue factor and low tissue factor pathway inhibitor levels in severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Possible association with clinical outcome. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2003;14:277.

25 Haning R, Strawn E, Nolten W. Pathophysiology of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:220.

26 Asch R, Li H, Balmaceda J, et al. Severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in assisted reproductive technologies: Definition of high risk groups. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:1395.

27 Golan A, Ron-El R, Soffer Y, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: An update review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1989;44:430.

28 Navot D, Relou A, Birkenfeld A, et al. Risk factors and prognostic variables in the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:210.

29 Blankstein J, Shalev J, Saadon T, et al. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Prediction by number and size of preovulatory ovarian follicles. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:597.

30 Charbonnel B, Krempt M, Blanchard P, et al. Induction of ovulation in polycystic ovary syndrome with a combination of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone analogue and exogenous gonadotropins. Fertil Steril. 1987;47:920.

31 Haning RV, Austin CW, Carlson H, et al. Plasma estradiol is superior to ultrasound and urinary estradiol glucuronide as a predictor of ovarian hyperstimulation during induction of ovulation with menotropins. Fertil Steril. 1983;40:31.

32 Roden S, Juvin K, Homasson JP, et al. An uncommon etiology of isolated pleural effusion: The ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Chest. 2000;118:256.

33 Benadiva CA, David O, Kligman I, et al. Withhold gonadotropins administration is an effective alternative for prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:724.

34 Dhont M, Van der Straeten F, DeSutter P. Prevention of severe ovarian hyperstimulation by coasting. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:847.

35 Sher G, Salem R, Feinman M, et al. Eliminating the risk of life-endangering complication following overstimulation with menotropin fertility agents: A report on women undergoing in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:1009.

36 Sher G, Zouves C, Feinman M, et al. “Prolonged coasting”: An effective method for preventing severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:3107.

37 Tozer AJ, Iles RK, Iammarrone E, et al. The effects of “coasting” on follicular fluid concentrations of vascular endothelial growth factor in women at risk of developing ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:522.

38 Levinsohn-Tavor O, Friedler S, Schachter M, et al. Coasting—what is the best formula? Hum Reprod. 2003;18:937.

39 Shalev E, Giladi Y, Matilsky M, et al. Decreased incidence of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome in high risk in vitro fertilization patients receiving intravenous albumin: A prospective study. Hum Reprod. 1995;10:1373.

40 Aboulghar M, Evers JH, Al-Inany H. Intravenous albumin for preventing severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A Cochrane review. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:3027.

41 Belliver J, Munoz EA, Soares SR, et al. Intravenous albumin does not prevent moderate-severe hyperstimulation syndrome in high-risk IVF patients: A randomized study. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2283.

42 Graf MA, Fischer R, Naether OG, et al. Reduced incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome by prophylactic infusion of hydroxyethyl starch solution in an in vitro fertilization programme. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:2599.

43 Gamzu R, Almog B, Levin Y, et al. Efficacy of hydroxyethyl starch and Haemaccel for the treatment of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:1302.

44 Rabinerson D, Ben Rafael Z, Keslin J, et al. 10% hydroxyethyl starch for plasma expansion in the treatment of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: A case report. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:68.

45 de Jong D, Macklon NS, Mannaerts BM, et al. High dose gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonist (ganirelix) may prevent ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome caused by ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:573.

46 Imoedemhe DAG, Chan RCW, Sigue AB, et al. A new approach to the management of patients at risk of ovarian hyperstimulation in an in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1991;6:1088.

47 Itskovitz J, Boldes R, Barlev A, et al. The induction of LH surge and oocyte maturation by GnRH analogue (buserelin) in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for in vitro fertilization. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1988;2:165.

48 Itskovitz-Eldor J, Kor S, Mannaerts B. Use of a single bolus of GnRH agonist triptorelin to trigger ovulation after GnRH antagonist ganirelix treatment in women undergoing ovarian stimulation for assisted reproduction, with special reference to the prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome: Preliminary report: Short communication. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:1965.

49 Lanzone A, Fulghesu AM, Villa P, et al. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist versus human chorionic gonadotropin as a trigger of ovulation in polycystic ovarian disease gonadotropin hyperstimulated cycles. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:35.

50 Lewit N, Kol S, Manor D, et al. The use of GnRH analogs for induction of the preovulatory gonadotropin surge in assisted reproduction and prevention of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. 1995;4:13.

51 Lewit N, Kol S, Manor D, et al. Comparison of GnRH analogs and hCG for the induction of ovulation and prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS): A case-control study. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1399.

52 Kol S. Luteolysis induced by a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist is the key to prevention of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1.

53 Tummon IS, Contag SA, Thornhill AR, et al. Cumulative first live birth after elective cryopreservation of all embryos due to ovarian hyperresponsiveness. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:309.

54 Olivennes F, Fanchin R, Bouchard P, et al. Triggering of ovulation by a gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist in patients pretreated with a GnRH antagonist. Fertil Steril. 1996;66:151.

54 Fluker M, Copeland J, Yuzpe AA. An ounce of prevention: Outpatient management of the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:821.

55 Aboulghar M, Mansour R, Serour G, et al. Ultrasonically guided vaginal aspiration of ascites in the treatment of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:933.

56 Levin I, Amog B, Avni A, et al. Effect of paracentesis of ascitic fluid on urinary output and blood indices in patients with severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:986.

57 Padilla S, Zamaria S, Baramki T, et al. Abdominal paracentesis for the ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome with severe pulmonary compromise. Fertil Steril. 1990;53:365.

58 Aboulghar MA, Mansour RT, Serour GI, et al. Management of severe hyperstimulation syndrome by ascitic fluid aspiration and intensive intravenous fluid therapy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:18.

59 Avecillas JF, Falcone T, Arroliga AC. Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:679-695.

60 Amarin ZO. Bilateral partial oophorectomy in the management of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:659.

61 Goldfarb J, Kinzer DJ, Boyle M, et al. Attitudes of in vitro fertilization and intrauterine insemination couples toward multiple gestation pregnancy and multifetal pregnancy reduction. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:815.

62 Ryan GL, Zhang SH, Dokras A, et al. The desire of infertile patients for multiple births. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:500.

63 Mathews TJ, MacDorman MF, Menacker F. Infant mortality statistics from the 1999 period linked birth/infant death data set. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2002;50:11.

64 Norwitz ER. Multiple pregnancy: Trends past, present and future. Infertil Reprod Med Clin North Am. 1998;9:351.

65 Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Venture SJ, et al. Births: Final data for 2001. Nat Vital Stat Rep. 2002;51:104.

66 Newman RB, Luke B. Neonatal and post-neonatal considerations. In: Newman RB, Luke B, editors. Multifetal Pregnancy. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:243.

67 Alexander G, Kogan M, Martin J. What are the fetal growth patterns of singletons, twins and triplets in the USA? Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1998;41:115.

68 Pharoah PO, Cooke T. Cerebral palsy and multiple births. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 1996;75:174.

69 Devine PC, Malone FD, Athanassiou A, et al. Maternal and neonatal outcome of 100 consecutive triplet pregnancies. Am J Perinatol. 2001;18:225-235.

70 Luke B, Keith LG. The contribution of singletons, twins and triplets to low birth weight, infant mortality and handicap in the United States. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:661.

71 Derom C, Vlietinck R, Derom R, et al. Increased monozygotic twinning rate after ovulation induction. Lancet. 1987;1:1236.

72 Bulmer MG. The Biology of Twinning in Man. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1970.

73 Milki AA, Jun SH, Hinckley MD, et al. Incidence of monozygotic twinning with blastocyst transfer compared to cleavage-stage transfer. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:503.

74 Wenstrom KD, Syrop CH, Hammit DG, et al. Increased risk of monochorionic twinning associated with assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:510.

75 Machin G, Bamforth F, Innes M, et al. Some perinatal characteristics of monozygotic twins who are dichorionic. Am J Med Genet. 1995;55:71.

76 Su LL. Monoamniotic twins: Diagnosis and management. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:995.

77 Callahan TL, Hall JE, Ettner SL, et al. The economic impact of multiple-gestation pregnancies and the contribution of assisted-reproduction techniques to their incidence. NEJM. 1998;339:573.

78 Goldfarb JM, Austin C, Lisbona H, et al. Cost-effectiveness of in vitro fertilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:18.

79 Cook R, Bradley S, Golombok S. A preliminary study of parental stress and child behaviour in families with twins conceived by in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3244.

80 The Practice Committee of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technology, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Guidelines on number of embryos transferred. Fertil Steril. 2004;82:773.

81 Healy D. Damaged babies from assisted reproductive technologies: Focus on the BESST (birth emphasizing a successful singleton at term) outcome. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:512.

82 Gardner DK, Surrey E, Minjarez D, et al. Single blastocyst transfer: A prospective randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:551.

83 Reynolds MA, Schieve LA, Jeng G, et al. Does insurance coverage decrease the risk for multiple births associated with assisted reproductive technology? Fertil Steril. 2003;80:16.

84 Reynolds MA, Schieve LA, Peterson HB. Insurance is not a magic bullet for the multiple birth problem associated with assisted reproductive technology. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:32.

85 Hansen M, Bower C, Milne E, et al. Assisted reproductive technologies and the risk of birth defects—a systematic review. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:328.

86 Van Steirteghem A, Bonduelle M, Devroey P, et al. Follow up of children born after ICSI. Hum Reprod Update. 2002;8:111.

87 Bennett SJ, Waterstone JJ, Cheng WC, et al. Complications of transvaginal ultrasound-directed follicle aspiration: A review of 2670 consecutive procedures. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1993;10:72.

88 Govaerts I, Devreler F, Delbaere A, et al. Short-term medical complications of 1500 oocyte retrievals for in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1998;77:239.

89 den Boon J, Kimmel CEJM, Nagel TC, et al. Pelvic abscess in the second half of pregnancy after oocyte retrieval for in vitro fertilization: Case report. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:2402.

90 Chetkowski RJ, Nass TE. Anesthesia and antibiotics in assisted reproduction. Assist Reprod Rev. 1992;2:36.

91 Van Os HC, Roozenburg BJ, Jansen-Caspers HAB, et al. Vaginal disinfection with povidone-iodine and the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:349.

92 Yaron Y, Peyser MR, Samuel D, et al. Infected endometriotic cysts secondary to oocyte aspiration for in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 1994;9:1759.

93 Coccia ME, Becattini C, Bracco GL, et al. Acute abdomen following dermoid cyst rupture during transvaginal ultrasonographically guided retrieval of oocytes. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1897.

94 Almog B, Rimon E, Yovel I, et al. Vertebral osteomyelitis: A rare complication of transvaginal ultrasound-guided oocyte retrieval. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:1250.

95 Whittemore AS, Harris R, Itnyre J, et al. Characteristics relating to ovarian cancer risk: collaborative analysis of 12 US case-control studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:1184.

96 Cohen J, Forman R, Harlap S, et al. IFFS expert group report on the Whittemore study related to the risk of ovarian cancer associated with the use of infertility agents. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:966.

97 Fischel S, Jackson P. Follicular stimulation for high tech pregnancies: Are we playing it safe? BMJ. 1989;299:309.

98 Heintz APM, Hacker NF, Lagasse LD. Epidemiology and etiology of ovarian cancer: A review. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:127.

99 Goldberg GL, Runowicz CD. Ovarian carcinoma of low malignant potential, infertility, and induction of ovulation—is there a link? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:853.

100 Rossing MA, Daling JR, Weiss NS, et al. Ovarian tumors in a cohort of infertile women. NEJM. 1994;331:771.

101 Priore GD, Robischon K, Phipps WR. Risk of ovarian cancer after treatment for infertility. NEJM. 1995;332:1300.

102 Potashnik G, Lerner-Geva L, Genkin L, et al. Fertility drugs and the risk of breast and ovarian cancers: Results of a long-term follow-up study. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:853.

103 Mosgaard BJ, Lidegaard O, Kjaer SK, et al. Infertility, fertility drugs, and invasive ovarian cancer: A case-control study. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:1005.

104 Dor J, Lerner-Geva L, Rabinovici J, et al. Cancer incidence in a cohort of infertile women who underwent in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2002;77:324.

105 Venn A, Watson L, Bruinsma F, et al. Risk of cancer after use of fertility drugs with in vitro fertilization. Lancet. 1999;354:1586.

106 Doyle P, Maconochie N, Beral V, et al. Cancer incidence following treatment for infertility at a clinic in the UK. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:2209.

107 Kashyap S, Moher D, Fung Kee Fung M, et al. Assisted reproductive technology and the incidence of ovarian cancer: A meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:785.

108 Practice Committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine. Fertility drugs and the risk of ovarian cancer. Accessible at www.asrm.org. Nov. 2003.