Chapter 8 Common problems after ICU

Until recently, an intensive care unit (ICU) stay was deemed successful if a patient survived to go to the ward. No consideration was taken of the patient dying on the ward or soon after leaving hospital or indeed if the patient went home with an appalling quality of life.

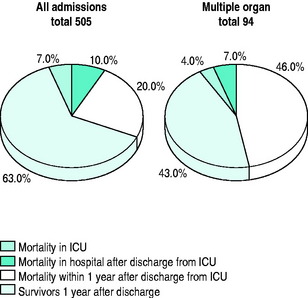

Mortality figures for patients leaving our own ICU recently are shown in Figure 8.1.

A Kings Fund report1 in 1989 concluded that it was necessary to look at the morbidity following critical illness as well as mortality: ‘There is more to life than measuring death’.

Publications such as that of the Audit Commission (Critical to Success)2 and that of the National Expert Group3 (Comprehensive Critical Care) have supported the development of follow-up for patients following a stay in intensive care. In 2007, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) began to take an interest in the rehabilitation of critically ill patients and it is hoped will make recommendations to facilitate the introduction of follow-up programmes in all hospitals looking after critically ill patients.

SETTING UP A FOLLOW-UP SERVICE

The logistics of running the service include arranging specific tests that may be required for the visit, such as pulmonary function tests, swabs for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), blood/urine for creatinine clearance. There may be special tests such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)4 for patients who had a tracheostomy during their stay in ICU.

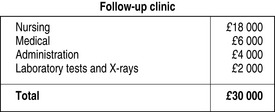

The service in Reading costs £30 000 annually which, in the context of the bigger picture (£4.5 million budget for our ICU), is a small price to pay (Figure 8.2). An unexpected bonus is that the clinic is often seen by the patients as a convenient place to make donations to the ICU.

SPECIFIC PROBLEMS POST-ICU

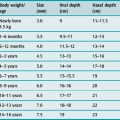

There are several quality-of-life tools used in follow-up studies (Table 8.1). Objective measurements may be inappropriate because they look at aspects such as return to work: often, patients in their 50s may not return to work after a traumatic episode, including ICU, and subjective measures would be more applicable, such as Perceived Quality Of Life (PQOL).

| Objective | |

| QALY | Quality of Life tool5 |

| Subjective | |

| HAD | Hospital Anxiety and Depression6 |

| PQOL | Perceived Quality of Life7 |

| EuroQol | ‘European’ tool8 |

| SF 36 | 36-item short-form survey9 |

TRACHEOSTOMY

Since percutaneous techniques performed by intensivists started to replace surgical tracheostomy in 1991, we have seen an increasing number of patients tracheostomised earlier in their ICU stay.

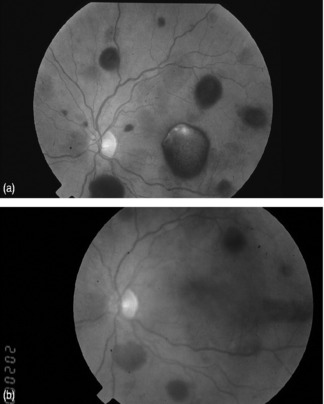

The long-term sequelae have been assessed by lung function tests, nasoendoscopy and MRI screening (Figure 8.3). There are minor cosmetic problems, such as tethering (Figure 8.4). Tethering is easily dealt with in ear, nose and throat outpatients under local anaesthetic.

More difficult to manage is tracheal stenosis, defined as a 15% reduction in tracheal diameter. However, there have only been two cases to date. These were seen in the first series of 30 cases.4

MOBILITY

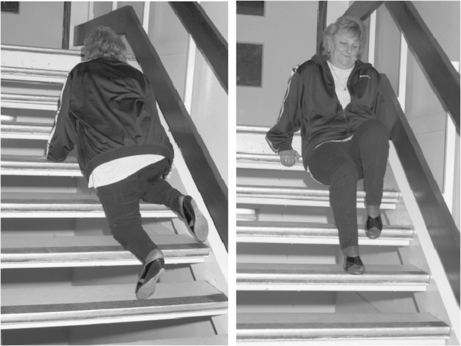

Even in the absence of trauma, patients can expect to need 9 months to 1 year to regain full mobility. This is usually due to a mixture of joint pain, stiffness and muscle weakness. In one study,10 the duration of ICU stay was associated with mobility problems probably associated with loss of muscle mass. If questioned, patients will often report climbing stairs on all fours and descending on their bottoms (Figure 8.5). Muscle wasting can present as a severe localised problem.

This may be associated with critical illness polyneuropathy (CIP),11 which not only prolongs ventilatory weaning but frequently both complicates and delays rehabilitation. Muscle relaxants have been implicated in the development of CIP12 but have not been shown to be statistically significant in terms of delayed weaning of intermittent positive-pressure ventilation and duration of stay in ICU.13

Until now, there have been no specific rehabilitation programmes for patients recovering from critical illness, although rehabilitation programmes for heart attack, stroke and respiratory disease are well established. A three-centre study has shown that a self-help physiotherapy guided rehabilitation exercise programme will speed up physical recovery after intensive care.14

SKIN

Patients complain of a variety of non-specific disorders, including hair loss and nail ridging. Severe pruritus used to be common and not amenable to treatment and was traced back to the use of high-molecular-weight starch solutions in ICU. Described in 2000,15 in 85 cardiac surgical patients, pruritus was absent in the 26 patients who did not receive starch, but there was a 22% incidence in the 59 patients who did receive starch. This is now supposedly less of a problem with the newer starches.

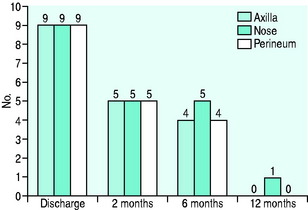

Colonisation with MRSA often persists for up to 9 months or longer (Figure 8.6). It is common to hear that patients are being treated as ‘lepers’ by their own family.

SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

In a group of 57 patients,16 there was a 39% incidence of sexual dysfunction, although in 4 patients, sex life had improved. Sexual dysfunction improves with time, from a frequency of about 26% at 2 months post-ICU down to 16% at 1 year.17 Sexual dysfunction is often thought to be a psychological problem but, interestingly, following severe burns, it has been reported that there is no correlation between the incidence of posttraumatic stress syndrome and sexual dysfunction.18 Nevertheless, withdrawing sexual intimacy because of fear of failure can damage relationships. Often sexual dysfunction may go untreated because people are too embarrassed to mention the problem when they have recovered from a life-threatening illness.

Sexual dysfunction affects both men and women. In men it usually manifests itself as impotence or inability to maintain an erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual activity. For management guidelines for erectile dysfunction, see Ralph and McNicholas.19

In females, sexual dysfunction may occur due to surgery or trauma to the pelvis. More commonly, there is a reduction in desire. Various lubricating gels can be used. As yet, the role of Viagra for women has to be determined. In 127 patients asked to fill in a questionnaire while attending the clinic, the incidence of sexual dysfunction was 45%.20 There was no link with gender but there was a close association with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

OTHER PHYSICAL PROBLEMS

A variety of other problems have been seen during follow-up:

PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

The story of ‘torture’ experiences is not unusual when you talk to an ex-ICU patient. The psychological impact of the experience may be formidable and may be resented by the patient. The memory of hearing that a patient is about to be ‘bagged’ was interpreted as being put into a body bag rather than a physiotherapy manoeuvre and the use of a tape measure was interpreted as being measured for a coffin and not as part of the cardiac output measurements. Previous studies demonstrate a high incidence of anxiety, depression and posttraumatic stress.21 It is common for patients to have memories of being trapped, of being unable to move easily, of being unable to see what is happening and of feeling intensely vulnerable. The anxiety of impending death is also reported.

Below is a typical nightmare of one of our patients:

There may be several reasons for these experiences (Table 8.2). There is a common belief that, when on ICU, it is better that a patient does not remember anything. However, it is increasingly realised that false memories or delusions during an ICU stay can have a significant impact on psychological recovery after ICU22 and factual memories of ICU may reduce anxiety.23

| Illness |

| Sedation technique |

| Withdrawal |

| No communication aids |

| Lack of clear night/day |

| Continuous noise of alarms |

| Sleep disturbance – lack of rapid-eye-movement sleep |

It now seems likely that delusional memories of ICU and nightmares are associated with PTSD.

PTSD is the development of characteristic symptoms after being subjected to a traumatic event. PTSD can be triggered by any memory or mention of something to do with the traumatic event and is characterised by intrusive recollections, avoidance behaviour and hyperarousal symptoms.24

Chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), previously known as myalgic encephalitis (ME), is thought to describe the condition of many patients post-ICU who have had a period of prolonged inactivity. CFS is diagnosed by the presence of fatigue at 6 months post-ICU with impairment of daily living, social and leisure pursuits and with no medically significant cause of the fatigue. There is no doubt that a graded exercise programme is of benefit to aid physical recovery in such ICU patients.14 Drugs such as fluoxetime (Prozac) do not seem to benefit such patients, even though there is a great temptation to use antidepressants in these patients.25

Various strategies to deal with the psychological sequelae of ICU stay have been tried.

DURING ICU STAY

CONCLUSION

It is important to assess patient satisfaction or dissatisfaction with their follow-up. This may be audited by questionnaire during their third visit to the follow-up clinic at 1 year post ICU discharge.35

The comments were very useful, e.g.:

In the UK follow-up clinics were recommended by the Audit Commission in 1999 (Criticial to Success)2 and in the Comprehensive Critical Care document in 20003, yet only a small number of hospitals have been able to fund such a service. Griffiths et al.36 demonstrated that clinics are not widely established and show marked heterogeneity. Of those established, only two-thirds are funded and most do not have a prenegotiated access to other outpatient services. It is hoped that NICE will support their growth and that the National Outreach Forum will support the idea that follow-up will be one of the quality indicators of a hospital’s resolve to set up a comprehensive service for patients who have been critically ill. Meanwhile there is an exponential increase in literature related to outcome following critical illness as health economists and intensivists try and make some sense out of the cost-effectiveness of intensive care.37–40 Further studies are under way. The DiPEx study seeks to obtain a variety of patient and relative experiences of critical care (www.dipex.org). I-CANUK is a website that is being set up to provide a forum and voice for those involved in patient care following intensive care discharge and to support research into potential therapies following critical illness. The results of the PraCTICaL (Pragmatic Randomised Controlled Trial of Intensive Care Follow-up clinics in improving longer-term outcomes trial from critical illness) should be available by the end of 2008.

1 Kings Fund. Intensive care in the United Kingdom; a report from the Kings Fund Panel. Anaesthesia. 1989;44:428-430.

2 Audit Commission. Critical to Success. The Place of Efficient and Effective Critical Care Services within the Acute Hospital. London: Audit Commission, 1999.

3 National Expert Group. Comprehensive Critical Care. A Review of Adult Critical Care Services. London: Department of Health, 2000.

4 Bernau F, Waldmann CS, Meanock C, et al. Long-term follow-up of percutaneous tracheostomy using ßow-loop and MRI scanning. Intens Care Med. 1996;22:S295.

5 Harris J. Qualifying the value of life. J Med Ethics. 1987;13:117-173.

6 Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatry Scand. 1983;67:361-370.

7 Patrick DL, Davis M, Southerland LI, et al. Quality of life following intensive care. J Gen Int Med. 1988;3:218-223.

8 Williams A. The Euro Qol – a new facility for the measurement of health related quality of life. Health Policy II. 1990;16:199-208.

9 Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473-481.

10 Jones C, Griffiths RD. Identifying post intensive care patients who may need physical rehabilitation. Clin Intens Care. 2000;11:35-38.

11 Leijten FSS, de Weerd AW. Critical illness polyneuropathy. A review of literature, definition and pathophysiology. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1994;96:10-19.

12 Barohn RJ, Jackson CE, Rogers SJ, et al. Prolonged paralysis due to non-depolarising neuromuscular blocking agents and corticosteroids. Muscle Nerve. 1994;17:647-654.

13 Zifko UA, Zipko HT, Bolton CF. Clinical and electrophysiological finding in critical illness polyneuropathy. J Neurol Sci. 1998;159:186-193.

14 Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffith RD. Rehabilitation after critical illness, a randomised controlled trial. Crit Care Med. 31, 2003. 2456–61

15 Morgan PW, Berridge JC. Giving long-persistent starch as volume replacement can cause pruritis after cardiac surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:676-699.

16 Quinlan J, Gager M, Fawcett D, et al. Sexual dysfunction after intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:348.

17 Quinlan J, Waldmann CS, Fawcett D. Sexual dysfunction after intensive care. Br J Anaesth. 1998;81:809-810.

18 De Rios MD, Norac A, Achauer BH. Sexual dysfunction and the patient with burns. Burn Care Rehabil. 1997;18:37-42.

19 Ralph D, McNicholas T. UK management guidelines for erectile dysfunction. Br Med J. 2000;321:499-503.

20 Griffiths J, Gager M, Alder N, et al. A self-report based study of the incidence and associations of sexual dysfunction in the survivors of intensive care treatment. Intens Care Med. 2006;32:445-451.

21 Koshy G, Wilkinson A, Harmsworth A, et al. Intensive care unit follow-up program at a district general hospital. Intens Care Med. 1997;23:S160.

22 Griffiths RD, Jones C, McMillan I. Where is the harm in not knowing? Care after intensive care. Clin Intens Care. 1996;7:144-145.

23 Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphries G. Factual memories of intensive care may reduce anxiety post-ICU. Br J Anaesth. 2000;82:793.

24 Horowitz MJ. Stress response syndromes – a review of post-traumatic stress and adjustment disorders. In: Wilson JP, Raphael B, editors. International Handbook of Traumatic Stress Syndromes. New York: Plenum Press; 1993:49-60.

25 Jones C, Skirrow P, Griffiths RD, et al. The characteristics of patients given antidepressants while recovering from critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:666.

26 Kollef MH, Levy NT, Ahrens TS, et al. The use of continuous IV sedation is associated with prolongation of mechanical ventilation. Chest. 1998;114:541-548.

27 Kreiss JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, et al. Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1471-1477.

28 Ledingham IM, Watt I. Influence of sedation in multiple trauma patients. Lancet. 1983;8336:1270.

29 Cremer OL, Moons GM, Bouman EAC, et al. Long-term propofol infusion and cardiac failure in adult head-injured patients. Lancet. 2001;357:117-118.

30 Conway DH, Eddleston J, Turner S. Prevalence of oral sedation dependency following intensive care. Intens Care Med. 1999;25(suppl. 1):S169.

31 Meagher DJ. Delirium: optimising management. Br Med J. 2001;322:144-149.

32 Shapiro BA, Warren J, Egol AB, et al. Practice parameters for intravenous analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit: an executive summary. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1596-1600.

33 Etchels MC. Personal communication. ICU talk. Available online at: www.computing.dundee.ac.uk/projects/icutalk

34 Waldmann CS, Tseng P, Meulman P, et al. Aromatherapy in the intensive care unit. Care Crit Ill. 1993;9:170-174.

35 Hames KC, Gager M, Waldmann CS. Patient satisfaction with specialist ICU follow-up. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:372.

36 Griffiths JA, Barber VS, Cuthbertson BH, et al. A national survey of intensive care follow up clinics. Anaesthesia. 2006;61:950-955.

37 Griffiths RD, Jones C. Intensive Care Aftercare. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 2002.

38 Angus DC, Carlet J. Surviving Intensive Care. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 2003. Update in Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine 39

39 Wu A, Gao F. Long term outcomes in survivors of critical illness. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:1049-1052.

40 Herridge MS, Cheung A, Tansey C, et al. One year outcomes in survivors of the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:683-693.