Chapter 1 Collection and handling of blood

In investigating physiological function and malfunction of blood, accurate and precise methodology is essential to ensure, as far as possible, that tests do not give misleading information because of technical errors. Obtaining the specimen is the first step towards analytic procedures. It is important to use appropriate blood containers and to avoid faults in specimen collection, storage and transport to the laboratory. Venous blood is generally used for most haematological examinations and for chemistry tests; capillary skin puncture samples can be almost as satisfactory for some purposes if a free flow of blood is obtained (see p. 4), but in general this procedure should be restricted to children and to some ‘point-of-care’ screening tests which require only a drop or two of blood. Bone marrow aspirates are described in Chapter 7.

Biohazard precautions

Special care must be taken to avoid risk of infection from various pathogens during all aspects of laboratory practice, and the safety procedures described in Chapter 24 must be followed as far as possible when collecting blood. The operator should wear disposable plastic or thin rubber gloves. It is also desirable to wear a protective apron or gown, as well as glasses or goggles, if necessary. Care must be taken to prevent injuries, especially when handling syringes, needles and lancets.

Disposable sterilized syringes, needles and lancets should be used if at all possible, and they should never be re-used. Re-usable items must always be sterilized after use (see Chapter 24).

Standardized procedure

The constituents of the blood may be altered by a number of factors which are listed in Box 1.1. It is important to have a standard procedure for the collecting and handling of blood specimens. Recommendations for standardizing the procedure have been published.1–3

Venous blood

It is now common practice for specimen collection to be undertaken by specially trained phlebotomists, and there are published guidelines which set out an appropriate training programme.1,4

Phlebotomy Tray

It is convenient to have a tray which contains all the requirements for blood collection (Box 1.2).

Disposable Plastic Syringes and Disposable Needles

The needles should not be too fine, too large, or too long; those of 19 or 21G* are suitable for most adults. 23G are suitable for children and ideally should have a short shaft (about 15 mm). It may be helpful to collect the blood by means of a winged (‘butterfly’) needle connected to a length of plastic tubing which can be attached to the nozzle of the syringe or to a needle for entering the cap of an evacuated container (see below).

Specimen Containers

The common containers for haematology tests are available commercially with dipotassium, tripotassium, or disodium ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) as an anticoagulant, and they are marked at a level to indicate the correct amount of blood to be added. Containers are also available containing trisodium citrate, heparin or acid-citrate-dextrose, as well as containers with no additive which are used when serum is required. Design requirements and other specifications for specimen collection containers have been described in a number of national and international standards, e.g. that of the International Council for Standardization in Haematology,5 and there is also a European standard (EN 14820). Unfortunately, there is not yet universal agreement regarding the colours for identifying containers with different additives; phlebotomists should familiarize themselves with the colours used by their own suppliers.

Phlebotomy Procedure

Blood is best withdrawn from an antecubital vein or other visible veins in the forearm by means of either an evacuated tube or a syringe. It is usually recommended that the skin should be cleaned with 70% alcohol (e.g. isopropanol) or 0.5% chlorhexidine, and allowed to dry spontaneously before being punctured; however, some doubts have been expressed on the utility of this practice for preventing infection at the venepuncture site.6 Care must also be taken when using a tourniquet to avoid contaminating it with blood because infection risks have been reported during blood collection.7 The tourniquet should be applied just above the venepuncture site and released as soon as the blood begins to flow into the syringe or evacuated tube – delay in releasing it leads to fluid shift and haemoconcentration as a result of venous blood stagnation.4 Except for very young children, it should be possible with practice to obtain venous blood even from patients with difficult veins. A butterfly needle is especially useful when a series of samples is required.

Post-phlebotomy Procedure

The phlebotomist should again check the patient’s identity and must make sure that it corresponds to the details on the request form. It is essential that every specimen, as well as the request form, is labelled with adequate patient identification immediately after the samples have been obtained. On the labels this should include at least surname and forename or initials, hospital number, date of birth and date and time of specimen collection. The same information must be given on the request form, together with ward or department, name of requesting clinician and test(s) requested. When relevant, a biohazard warning must also be affixed to the container and to the request form. If automated patient identification is available both the label and the request form should be bar-coded with the relevant data unless the sample is to be used for blood transfusion tests, in which case the label should be handwritten, with the name in full (see Chapter 21).

Waste Disposal

Without separating the needle from the syringe, place both, together with the used swab and any other dressings, in a puncture-resistant container, for disposal (see Chapter 24). If it is essential to dispose of the needle separately it should be detached from the syringe only with forceps or a similar tool. Alternatively, the needle can be destroyed in situ with a special device, e.g. Sharp-X (Biomedical Disposal Inc: www.biodisposal.com)

Capillary blood

Collection of Capillary Blood

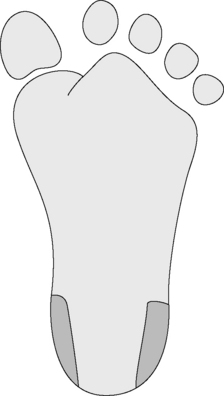

Skin puncture is carried out with a needle or lancet. In adults and older children, blood can be obtained from a finger; the recommended site is the distal digit of the third or fourth finger on its palmar surface, about 3–5 mm lateral from the nail bed. Formerly the ear lobe was commonly used, but it is no longer recommended because reduced blood flow renders it unrepresentative of the circulating blood.1 In infants, satisfactory samples can be obtained by a deep puncture of the plantar surface of the heel in the area shown in Figure 1.1. As the heel should be really warm, it may be necessary to bathe it in hot water. The central plantar area and the posterior curvature should not be punctured in small infants to avoid the risk of injury and possible infection to the underlying tarsal bones, especially in newborns.

There are methods for collecting the blood into a capillary tube fixed into the cap of a microcontainer to allow the blood to pass by capillary action into the container (e.g. Microtainer*).8 In another system (Unopette*), a calibrated capillary is completely filled with blood and linked to a pre-measured volume of diluent.9 An adequate puncture with a free flow of blood can also enable a larger volume to be collected, drop by drop, into a plastic or glass container.10

Blood Film Preparation

Ideally, blood films should be made immediately the blood has been collected. As blood samples are usually sent to the laboratory after a variable delay there are advantages in preparing blood films when the phlebotomy is carried out. The phlebotomy tray might include some clean glass slides and spreaders, and phlebotomists should be given appropriate training for film preparation as described in Chapter 4. An automated device for making smears is also available.11 When films are not made on site they should be made in the laboratory without delay as soon as the specimens have been received.

Differences between capillary and venous blood

Venous blood and capillary blood are not quite the same. Blood from a skin puncture is a mixture of blood from arterioles, veins and capillaries, and it contains some interstitial and intracellular fluid.1,4,12 Although some studies have suggested that there are negligible differences when a free flow of blood has been obtained,13 others have shown definite differences in composition between skin puncture and venous blood samples in neonates,14 children15 and adults.16 The differences may be exaggerated by cold with resulting slow capillary blood flow.4

The packed cell volume (PCV), red cell count (RBC) and haemoglobin concentration (Hb) of capillary blood are slightly greater than in venous blood. The total leucocyte and neutrophil counts are higher by about 8%, the monocyte count by about 12%, and in some cases by as much as 100%, especially in children. Conversely, the platelet count appears to be higher in venous than in capillary blood; this is on average by about 9% and in some cases by as much as 32%.14–16 This may be due to adhesion of platelets to the site of the skin puncture.

Serum

The difference between plasma and serum is that the latter lacks fibrinogen and some of the coagulation factors. Blood collected in order to obtain serum should be delivered into sterile tubes with caps or commercially available plain (non-anticoagulant) evacuated collection tubes and allowed to clot undisturbed for about 1 h at room temperature.* Then loosen the clot gently from the container wall by means of a wooden stick, or a thin plastic or glass rod. Rough handling will cause lysis. Close the tube with a cap/stopper. Some products contain a clot activator combined with a gel for accelerated separation of serum, e.g. Serum separator tubes (BD Ltd).

Defibrinating Whole Blood

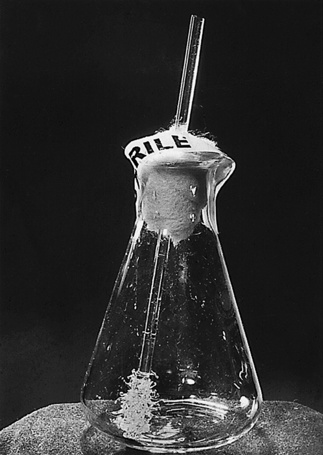

When the red cells are required, as in the investigation of certain types of haemolytic anaemia, the sample can be defibrinated. The morphology of the red cells and the leucocytes is well preserved. This can be performed by placing the blood in a conical flask containing a central glass rod on to which small pieces of glass capillary have been fused (Fig. 1.2). The blood is whisked around the central rod by moderately rapid rotation of the flask. Coagulation is usually complete within about 5 min, with most of the fibrin collecting on the central rod. When fibrin formation seems complete, the glass rod should be removed from the flask. If serum is required, the blood may be centrifuged and the serum can be obtained quickly and in relatively large volumes.

Anticoagulants

EDTA is used for blood counts; sodium citrate is used for coagulation testing and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. For better long-term preservation of red cells for certain tests and for transfusion purposes, citrate is used in combination with dextrose in the form of acid-citrate-dextrose (ACD), citrate-phosphate-dextrose (CPD) or Alsever’s solution. Anticoagulant mixtures are also used to compensate for disadvantages in each and to meet the needs of the analytic process;18,19 these include ACD, CPD or heparin combined with EDTA and EDTA, citrate, or heparin combined with sodium fluoride. Any anticoagulant can be used for collecting blood for flow cytometry.17,19

Ethylenediaminetetra-acetic Acid (EDTA)

The sodium and potassium salts of EDTA are powerful anticoagulants and they are especially suitable for routine haematological work. EDTA acts by its chelating effect on the calcium molecules in blood. To achieve this requires a concentration of 1.2 mg of the anhydrous salt per ml of blood (c 4 mmol). The dipotassium salt is very soluble (1650 g/l) and is to be preferred on this account to the disodium salt which is considerably less soluble (108 g/l).20 Coating the inside surface of the blood collection tube with a thin layer of EDTA improves the speed of its uptake by the blood.

The dilithium salt of EDTA is equally effective as an anticoagulant,21 and its use has the advantage that the same sample of blood can be used for chemical investigation. However, it is less soluble than the dipotassium salt (160 g/l).

The tripotassium salt dispensed in liquid form has been recommended in the USA by NCCLS.3 However, blood delivered into this solution will be slightly diluted, and the tripotassium salt produces some shrinkage of red cells which results in a 2–3% decrease in PCV within 4 hours of collection, followed by a gradual increase in mean cell volume (MCV). By contrast, there are negligible changes when the dipotassium salt is used.1,4 Accordingly, the International Council for Standardization in Haematology recommends the dipotassium salt at a concentration of 1.50–2.2 mg/ml of blood; the tripotassium salt may be accepted as an alternative.22 Na3-EDTA is not recommended because of its high pH.

Excess of EDTA, irrespective of which salt, affects both red cells and leucocytes, causing shrinkage and degenerative changes. EDTA in excess of 2 mg/ml of blood may result in a significant decrease in PCV by centrifugation and increase in mean cell haemoglobin concentration (MCHC).4 The platelets are also affected; excess of EDTA causes them to swell and then disintegrate, causing an artificially high platelet count, as the fragments are large enough to be counted as normal platelets. Care must therefore be taken to ensure that the correct amount of blood is added, and that by repeated inversions of the container the anticoagulant is thoroughly mixed in the blood added to it. Blood films made from EDTA blood may fail to demonstrate basophilic stippling of the red cells in lead poisoning. EDTA has also been shown to cause leuco-agglutination affecting both neutrophils and lymphocytes,23 and it is responsible for the activity of a naturally occurring antiplatelet auto-antibody which may sometimes cause platelet adherence to neutrophils in blood films. Monocyte activation measured by release of tissue factor and tumour necrosis factor activity has been reported as being lower with EDTA than with citrate and heparin. Similarly, neutrophil activation measured by lipopolysaccharide-induced release of lactoferrin is low with EDTA. EDTA also appears to suppress platelet degranulation.24

Trisodium Citrate

For coagulation studies, 9 volumes of blood are added to 1 volume of 109 mmol/l sodium citrate solution (32 g/l of Na3C6H5O7.2H2O*).25 This ratio of anticoagulant to blood is critical as osmotic effects and changes in free calcium ion concentration affect coagulation test results. This ratio of citrate to blood may need to be adjusted for samples with a high haematocrit requiring coagulation studies (see Chapter 18).

For the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), four volumes of blood are added to 1 volume of the sodium citrate solution (109 mmol/l) and immediately well mixed with it. The mixture is taken up in a Westergren tube.26

Heparin

However, heparin is not suitable for blood counts as it often induces platelet and leucocyte clumping.4,27,28 Nor should it be used for making blood films as it gives a faint blue coloration to the background when the films are stained by Romanowsky dyes, especially in the presence of abnormal proteins. It inhibits enzyme activity17 and it should not be used in the study of polymerase chain reaction with restriction enzymes.29

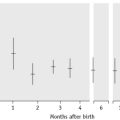

Effects of storage on the blood count

Various changes take place in anticoagulated blood when it is stored at room temperature, and these changes occur more rapidly at higher ambient temperatures. These occur regardless of the anticoagulant, although they are less marked in blood in ACD, CPD or Alsever’s solution than in EDTA blood and greater in the tripotassium salt than in the dipotassium salt of EDTA. The red cell count, white cell count, platelet count and red cell indices are usually stable for 8 h after blood collection, although as the red cells start to swell the PCV and MCV start to increase, osmotic fragility increases and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate decreases. When the blood is kept at 4°C the effects on the blood count are not usually significant for up to 24 h. Thus, for many purposes blood may safely be allowed to stand overnight in the refrigerator if precautions against freezing are taken. Nevertheless, it is best to count leucocytes and especially platelets within 2 h and it should be noted that the fall in leucocyte count and a progressive fall in the absolute lymphocyte count may become marked within a few hours, especially if there is an excessive amount of EDTA (>4.5 mg/ml).19 Storage beyond 24 h at 4°C results in erroneous data for automated white cell differential counts although the extent depends on instrument performance and the manufacturer’s recommendation, which should be followed when an automated counting method is employed. One study using an aperture impedance analyser on blood left at room temperature showed WBC and neutrophils to be stable for 2–3 days but other leucocytes were stable for only a few hours.30

Coagulation test stability is critical for diagnosis and treatment of coagulopathies; NCCLS has recommended that tests be carried out within 2 h when the blood or plasma is stored at 22–24°C, 4 h at 4°C, 2 weeks at −20°C, and 6 months when stored at −70°C.3

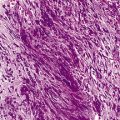

Effects of storage on blood cell morphology

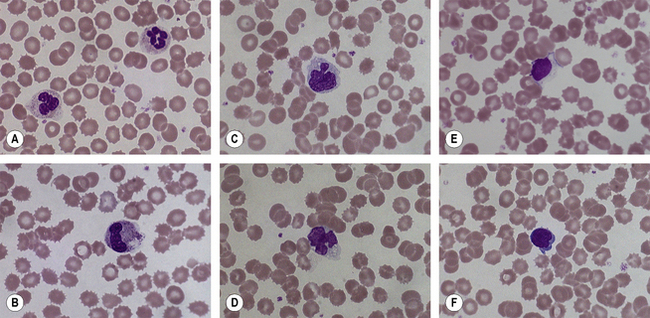

Changes in blood cell morphology of stored samples occur within a few hours of blood collection. The changes are not solely due to the presence of an anticoagulant for they also occur in defibrinated blood. Irrespective of anticoagulant, films made from blood which has been standing for <1 h at room temperature are not easily distinguished from films made immediately after collection of the blood. By 3 h, changes may be discernible and by 12–18 h these become striking. Some but not all neutrophils are affected; their nuclei may stain more homogeneously than in fresh blood, the nuclear lobes may become separated and the cytoplasmic margin may appear ragged or less well defined; small vacuoles appear in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1.3A,B). Some or many of the large monocytes develop marked changes; small vacuoles appear in the cytoplasm and the nucleus undergoes irregular lobulation which may almost amount to disintegration (Fig. 1.3C). Lymphocytes undergo similar changes: a few vacuoles may be seen in the cytoplasm, nuclei stain more homogeneously than usual and in some the nucleus undergoes budding, giving rise to nuclei with two or three lobes (Fig. 1.3D–F). Normal red cells are little affected by standing for up to 6 h at room temperature. Longer periods lead to progressive crenation and sphering (Fig. 1.3B,E,F). With an excess of EDTA, a marked degree of crenation occurs within a few hours. All the above changes are retarded but not abolished in blood stored at 4°C. Their occurrence underlines the importance of making films as soon as possible after the blood has been collected. But a delay of up to 3 h is permissible.

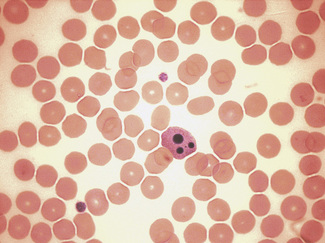

These artefactual changes must be distinguished from apoptosis which is a controlled process of programmed cell death related to mitochondrial dysfunction in which cytokines and growth factors regulating cell survival are depleted or inhibited,31,32 Apoptosis is characterized morphologically (Fig. 1.4) by cell shrinkage with cytoplasmic condensation around the nuclear membrane and indentations in the nucleus, followed by its fragmentation; finally the cell remnants form dense basophilic masses (the apoptotic bodies). Apoptotic neutrophils with a single apoptotic body may be confused with nucleated red cells if the cytoplasmic features are not appreciated. The remnants are removed from the circulation by phagocytosis and usually in a film only an occasional apoptotic cell is seen, surrounded by viable cells;33 more frequent apoptotic cells can be seen in leukaemia.

1 Tatsumi N., Miwa S., Lewis S.M., International Council for Standardization in Haematology/International Society of Hematology. Specimen collection, storage, and transportation to the laboratory for hematological tests. Int J Hematol. 2002;75:261-268.

2 CLSI. Procedures for the collection of diagnostic blood specimens by venipuncture. Approved standard, 6th ed. Wayne PA: CLSI, 2007. Document H3-A6

3 NCCLS. Tubes and additives for venous blood specimen collection. Approved standard, 5th ed. Wayne PA: NCCLS, 2003.

4 Van Assendelft O.W., Simmons A. Specimen collection, handling, storage and variability. In: Lewis S.M., Koepke J.A., editors. Hematology Laboratory Management and Practice. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1995:109-127.

5 Tatsumi N., van Assendelft O.W., Naka K. ICSH recommendation for blood specimen collection for hematological analysis. Lab Hematol. 2002;8:1-6.

6 Sutton C.D., White S.A., Edwards R. A prospective controlled trial of the efficacy of isopropyl alcohol wipes before venesection in surgical patients. Ann R Coll Surg. 1999;81:183-186.

7 Golder M., Chen C.L.H., O’Shea S., et al. Potential risk of cross-infection during peripheral-venous access by contaminated tourniquets. Lancet. 2000;355:44.

8 Meitis S. Skin puncture and blood collection techniques for infants: updates and problems. Clin Chem. 1988;34:1890-1894.

9 Hicks J.R., Rowland G.L., Buffone G.J. Evaluation of a new blood collection device (‘Microtainer’) that is suitable for pediatric use. Clin Chem. 1976;22:2034-2036.

10 Freudlich M.H., Gerarde H.W. A new, automatic disposable system for blood count and hemoglobin. Blood. 1963;21:648-655.

11 Tatsumi N., Pierre R. Automated image processing; past, present, and future of blood cell morphology identification. Clin Lab Med. 2002;22:299-316.

12 Conway A.M., Hinchliffe R.F., Earland J., et al. Measurement of hemoglobin using single drops of skin puncture blood: is precision acceptable? J Clin Pathol. 1998;51:248-250.

13 Yang Z.-W., Yang S.-H., Chen L., et al. Comparison of blood counts in venous, finger tip and arterial blood and their measurement variation. Clin Lab Haematol. 2001;23:155-159.

14 Kayiran S.M., Özbek N., Turan M., et al. Significant differences between capillary and venous complete blood counts in the neonatal period. Clin Lab Haematol. 2003;25:9-16.

15 Daae L.N.W., Hallerud M., Halvorsen S. A comparison between haematological parameters in ‘capillary’ and venous blood samples from hospitalized children aged 3 months to 14 years. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1988;51:651-654.

16 Daae L.N.W., Halvorsen S., Mathison P.M., et al. A comparison between haematological parameters in ‘capillary’ and venous blood from healthy adults. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1988;48:723-726.

17 Narayanan S. The pre-analytic phase: an important component of laboratory medicine. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;113:429-457.

18 Tatsumi N. Universal anticoagulants. Japanese Society of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2003;13:158-168.

19 CLSI. Clinical application of flow cytometry: quality assurance and immunophenotyping of peripheral blood lymphocytes. Wayne PA: CLSI, 2007. Document H43-A2

20 Hadley G.G., Weiss S.P. Further notes on use of salts of ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) as anticoagulants. Am J Clin Pathol. 1955;25:1090-1093.

21 Sacker L.S., Saunders K.E., Page B., et al. Dilithium sequestrene as an anticoagulant. J Clin Pathol. 1959;12:254-257.

22 International Council for Standardization in Haematology. Recommendations for ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid anticoagulation of blood for blood cell counting and sizing. Am J Clin Pathol. 1993;100:371-372.

23 Deal I., Hernandez A.M., Pierre R.V. Ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid-associated leukoaggulutination. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:338-340.

24 Engstad C.S., Gutteberg T.J., Osterud B. Modulation of cell activation by four commonly used anticoagulants. Thromb Haemost. 1997;77:690-696.

25 Ingram G.I.C., Hills M. The prothrombin time test; effect of varying citrate concentration. Thromb Haemost. 1976;36:230-236.

26 International Committee for Standardization in Haematology. Recommendation for measurement of erythrocyte sedimentation rate of human blood. Am J Clin Pathol. 1977;66:505-507.

27 Salzman E.W., Rosenberg R.D. Effect of heparin and heparin fractions on platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest. 1980;65:64-73.

28 Hirsh J., Levine N.M. Low molecular weight heparin. Blood. 1992;79:1-9.

29 Yokota M., Tatsumi N., Nathalang O., et al. Effects of heparin on polymerase chain reaction for blood white cells. J Clin Lab Anal. 1999;13:133-140.

30 Gulati G.L., Hyland L.J., Kocher W., et al. Changes in automated complete blood cell count and differential leucocyte count results induced by storage of blood at room temperature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126:336-342.

31 Kerr J.F., Wylie A.H., Curie A.R. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in tissue kinetics. Br J Cancer. 1972;26:239-257.

32 Wylie A.H., Kerr J.F.R., Currie A.R. Cell death: the significance of apoptosis. Int Rev Cytol. 1980;68:251-306.

33 Lach-Szyrma V., Brito-Babapulle F. The clinical significance of apoptotic cells in peripheral blood smears. Clin Lab Haematol. 1999;21:277-280.