CHAPTER 16 Colectomy

BACKGROUND

There are many indications for both partial and total colectomy. These include malignant, benign, ischemic, inflammatory, and infectious processes. The most common indications for colon and rectal resection are addressed individually later in the chapter. Common terms used to describe the types of colon and rectal operations are described in Table 16-1.

| Type of Resection | Description |

|---|---|

| Segmental colectomy | Removal of a portion of the colon (e.g., right, transverse, left, or sigmoid). |

| Total abdominal colectomy | Removal of the entire abdominal colon, leaving the rectum and creation of an end ileostomy or ileorectal anastomosis. |

| End stoma | Intestinal diversion involving division and exteriorization of the colon (colostomy) or terminal ileum (ileostomy) through the skin. The distal colon is then either brought out as a mucous fistula or left in the abdomen as a Hartmann’s pouch. |

| Loop stoma | A loop of either colon or ileum is exteriorized and opened, but not divided. |

| Hartmann’s pouch | An end stoma is created from proximal bowel; distal bowel is closed and remains in the pelvis. |

| Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (Park’s pouch, J-pouch) | After total proctocolectomy, the terminal ileum is used to create a reservoir that is connected to the anus as a “neorectum.” |

| Total mesorectal excision | En bloc removal of the mesorectum along with the rectum for rectal cancers of the mid and distal rectum. This is carried out by dissection in the plane between the fascia propria of the rectum and the presacral fascia. |

| Low anterior resection | Resection of the upper rectum; an anastomosis is formed between the colon and distal rectum. |

| Abdominoperineal resection | Total mesorectal excision of the rectum, surrounding tissues, and lymph nodes via abdominal and perineal approaches; creation of an end stoma. |

| Total proctocolectomy | Removal of the entire colon and rectum. Ileoanal pouch reconstruction or end ileostomy is required. |

INDICATIONS FOR COLORECTAL RESECTION

I. Sporadic Cancer and Inherited Polyposis Syndromes

A. Colon adenocarcinoma is the third most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States. Surgical resection is the initial treatment of choice for most colon cancers, although postoperative (adjuvant) chemotherapy plays an important role in the management of patients with nodal metastases. Surgery is aimed at removing the primary cancer with tumor-free margins, as well as the associated bowel mesentery and regional lymph nodes. In practice, the extent of resection is dictated by the location of the lesion and the colonic blood supply. For example, cecal tumors are treated with right hemicolectomy, an operation that involves ligation of the ileocolic, right colic, and right branch of the middle colic vessels, and resection of the segment of colon fed by these vessels. When curative resection is not possible, resection of the primary tumor is often still indicated to prevent complications associated with large tumors (e.g., obstruction and bleeding).

B. Rectal Adenocarcinoma: Because of the extraperitoneal position of the rectum within the pelvis (which allows for the administration of radiation therapy) and its proximity to parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves, rectal cancers are treated differently than are cancers of the colon. In the absence of nodal metastases, smaller lesions are typically treated with surgical resection and regional lymphadenectomy or with transanal local excision. The treatment of more advanced rectal cancers includes radiation and chemotherapy given before surgical excision of the tumor (i.e., neoadjuvant therapy). Large tumors may shrink significantly after chemoradiation, allowing for resection of most rectal cancers, with preservation of the anal sphincters (i.e., low anterior resection). In contrast, the distal location of some rectal cancers precludes sphincter preservation, despite neoadjuvant therapy, and mandates abdominoperineal resection (APR).

C. Adenomatous Polyps: Most colorectal carcinomas are believed to develop from adenomatous polyps. Polyps are generally classified by gross appearance as either pedunculated (i.e., with a stalk) or sessile (i.e., flat). Histologically, polyps are classified as tubular, tubulovillous, or villous. Tubular adenomas are the most common subtype, constituting 75% or more of colorectal adenomas, and have the least malignant potential of the three subtypes. Villous polyps constitute approximately 10% of colorectal adenomas, are most often found in the rectum, and have the greatest malignant potential. Polyps identified at colonoscopy should be excised completely. If complete endoscopic excision is not possible, segmental colectomy is indicated. If invasive carcinoma is found in the head of a pedunculated polyp, endoscopic resection is adequate treatment. Poorly differentiated histology, lymphovascular invasion, and the presence of invasive tumor within 1 mm of the resection margin mandate segmental colectomy.

D. Familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) is an autosomal dominant genetic syndrome most often associated with mutations of the APC gene. Patients with FAP have in excess of 100 precancerous polyps throughout the colon as early as their teens. If untreated, nearly all of these patients have colon cancer by age 40 years. Attenuated FAP is a phenotypic variant of the classic syndrome that is characterized by later onset of polyps, fewer polyps, and rectal sparing. The treatment of FAP is prophylactic surgical resection, usually performed after the onset of puberty. Surgical options include total proctocolectomy with permanent end ileostomy, total proctocolectomy with ileal pouch–anal anastomosis (IPAA) and total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis. The latter option should be offered only to carefully selected patients because it leaves the rectum in place, necessitating close subsequent surveillance. Patients with the attenuated FAP phenotype are sometimes offered a rectal sparing procedure, whereas patients with classic FAP are generally offered total proctocolectomy.

E. Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) accounts for 5% to 7% of all colon cancer diagnoses. HNPCC is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern and has been linked to mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes. The Amsterdam criteria are used to identify patients at high risk for HNPCC. In such patients, screening colonoscopy is recommended beginning at age 20 to 25 years. Total abdominal colectomy with ileorectal anastomosis is recommended if an adenomatous polyp or a colon carcinoma is identified. Patients with HNPCC are at an increased risk for rectal cancer, and annual proctoscopy is mandatory after colectomy.

II. Inflammatory Bowel Disease

A. Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory disease of the large intestine. The disease is marked by inflammation and ulceration of the bowel mucosa beginning at the rectum and extending proximally. UC is associated with a significantly elevated risk of colorectal cancer, and patients require frequent colonoscopic surveillance. There is no medical cure for UC, and current medical treatment is aimed at suppressing the inflammatory process. Although many patients remain symptom-free for prolonged periods, up to one third of patients ultimately require surgery.

1. Indications for surgery include intractable symptomatic disease despite medical therapy and the presence of dysplasia or cancer. Total proctocolectomy with ileostomy and total proctocolectomy with IPAA are curative and eliminate the risk of colon or rectal cancer.

2. Emergent indications for surgery in patients with UC include massive bleeding and toxic megacolon. Toxic megacolon occurs in approximately 10% of patients with UC and is characterized by acute dilation of the colon, accompanied by diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis. Initial treatment involves aggressive intravenous hydration, antibiotics, steroids, and cessation of narcotic pain medications. A worsening clinical appearance mandates surgical intervention, typically, total abdominal colectomy and creation of an end ileostomy.

B. Crohn’s disease is an inflammatory disease that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Disease limited exclusively to the colon occurs in approximately 15% of patients. As with UC, the initial treatment for Crohn’s colitis is medical. Surgical indications include failure of medical management, intestinal obstruction, fistula, fulminant colitis, toxic megacolon, massive bleeding, cancer, and malnutrition. Because more than half of all patients with Crohn’s disease experience a recurrence within 10 years of surgery, conservation of bowel length is an important surgical principle. The amount of colon resected depends on the extent and location of disease.

III. Benign Conditions

A. Diverticulitis results from microperforation of colonic diverticula. In uncomplicated diverticulitis, this perforation is contained and manifests as colonic and pericolonic inflammation. Diverticulitis may be complicated by abscess formation, fistulization between the colon and adjacent structures, free perforation, or obstruction. Initial episodes of uncomplicated diverticulitis are treated medically with antibiotics and dietary restriction until symptoms resolve. Recurrent uncomplicated diverticulitis and complicated diverticulitis are indications for surgical resection. In the stable patient with recurrent or complicated diverticulitis, medical treatment should be instituted to treat symptoms and reduce inflammation. After symptoms have subsided for at least 3 weeks, a colonoscopy should be performed to confirm the presence of diverticula, document the extent of disease, and exclude the presence of a neoplasm. Segmental resection of the involved colon, most commonly the sigmoid colon, with primary anastomosis can then be performed. Patients with complicated diverticulitis and evidence of free colonic perforation or sepsis should be operated on emergently and resection of the involved colon undertaken. Creation of a temporary colostomy, rather than an anastomosis, is often the preferred approach in such settings.

B. Sigmoid volvulus results from the torsion of the colon on its mesenteric axis. Volvulus may result in partial or complete obstruction of the bowel lumen, vascular compromise, bowel wall ischemia, and perforation. More than 80% of colonic volvuli involve the sigmoid colon. Patients are typically elderly, chronically debilitated, immobile, and institutionalized and present with abdominal distention, pain, and obstipation. Evidence of perforation and clinical deterioration are indications for emergent operative intervention, including sigmoid resection. In patients who are stable, reduction of the volvulus may be accomplished initially via colonoscopy or proctoscopy. Recurrence rates after endoscopic decompression are as high as 80% to 90%, and elective sigmoid resection should subsequently be undertaken.

C. Cecal volvulus, which is less common than sigmoid volvulus, is most commonly caused by congenital incomplete peritoneal fixation of the cecum in the right lower quadrant. Presenting symptoms are similar to those associated with sigmoid volvulus. Plain radiographs of the abdomen show a dilated cecum, often displaced to the left side of the abdomen. Endoscopic decompression is rarely successful. Treatment of suspected cecal volvulus, therefore, should include prompt right hemicolectomy, even in stable patients. In patients who cannot tolerate a lengthy procedure, surgical decompression and cecopexy (i.e., detorsion of the colon and fixation of the cecum in the right lower quadrant) is an acceptable alternative procedure, albeit one associated with a significant rate of recurrence.

D. Lower GI bleeding is most often caused by diverticulosis (50%) or arteriovenous malformations (30%). The initial treatment of lower GI bleeding includes resuscitation, correction of coagulopathy if present, and localization of the bleeding site. In 80% of patients with a diverticular bleed, bleeding stops spontaneously. In other patients, colonoscopic approaches or angioembolization can be used to control bleeding. Patients who continue to bleed require surgical intervention. Optimally, the site of bleeding is localized preoperatively with angiography, Technetium-99m–tagged red blood cell nuclear medicine scan, or colonoscopy, allowing for segmental resection of the involved colon. When preoperative localization is not possible, total abdominal colectomy is the procedure of choice.

E. Infectious colitis is most often treated with antibiotics, but occasionally necessitates colectomy. Pseudomembranous colitis is caused by the toxin-secreting bacterium Clostridium difficile. Most prevalent in hospitals and nursing home settings, pseudomembranous colitis is almost always associated with the previous use of antibiotics. Patients typically present with watery diarrhea and crampy abdominal pain. Generally, a course of oral metronidazole or vancomycin is adequate treatment for uncomplicated pseudomembranous colitis. Rarely, severe infection can lead to progressive colonic dilation, ischemia, and even perforation. In such fulminant cases, total abdominal colectomy with temporary ileostomy is required. The rectum is spared and an ileorectal anastomosis can be performed months later, when the patient is stable and well nourished.

F. Ischemic colitis occurs when there is insufficient blood flow to a portion of the colon. Risk factors for ischemic colitis include aortic aneurysms and transient hypotension. Most often, ischemia is confined to the mucosa and is transient. Occasionally, full-thickness ischemia may progress to perforation and sepsis, requiring emergency segmental colectomy. Evidence of perforation, massive bleeding, or clinical deterioration mandates operative exploration. Revascularization of the colon is rarely successful; thus, the procedure of choice is segmental colectomy with an end stoma, which may be reversed 3 to 4 months later.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

I. Colonoscopy: In general, patients should undergo colonoscopy before any elective colon resection to localize and determine the extent of disease and identify other pathology that could influence the surgical approach. Active inflammatory conditions (e.g., acute diverticulitis) may predispose to perforation and are, therefore, relative contraindications to colonoscopy.

II. Proctoscopy: Every patient diagnosed with rectal cancer should undergo preoperative rigid proctoscopy to determine the distance of the tumor from the anal verge, because this distance influences recommendations for preoperative chemotherapy and radiation as well as the surgical approach. Proctoscopic evaluation is also important for ruling out bleeding hemorrhoids or rectal varices as sources for lower GI bleeding and in establishing the presence of inflammation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.

III. Endorectal Ultrasound (ERUS): ERUS allows for an assessment of mesorectal lymph nodes and the depth of invasion of rectal cancers and is critical to preoperative staging.

IV. Barium Enema: A barium enema allows for the detection of polyps, cancers, diverticula, strictures, and fistulas, and is particularly useful when colonoscopy cannot be completed before surgery because of difficult anatomy or structural features (e.g., strictures) that prevent passage of the scope.

V. Computed Tomography (CT): A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is generally obtained on all patients with colon or rectal cancer to evaluate for adenopathy, tumor invasion of adjacent structures, and distant metastatic disease. In patients with abdominal pain and tenderness, CT scan can show evidence of bowel perforation (e.g., pneumoperitoneum) and provide information about the extent and location of inflammation, ischemia, or obstruction.

VI. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): MRI provides similar information to CT. Advantages of MRI compared with CT include more accurate delineation of the depth of rectal cancer invasion and identification of liver metastases. MRI may serve as an alternative to ERUS in the preoperative evaluation of patients with rectal cancers. Generally, MRI provides a more accurate assessment of nodal status, whereas ERUS provides a more accurate assessment of the depth of tumor invasion.

VII. Laboratory Tests

A. Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) is a serum glycoprotein that may be elevated in patients with primary or metastatic colon cancer. A serum CEA level is obtained before resection to establish a baseline level. Serial CEA levels are also followed after resection to screen patients for evidence of cancer recurrence.

VIII. Additional Preoperative Considerations

A. Until recently, it was widely accepted that all patients should undergo bowel preparation prior to elective colon resection to purge the colon of fecal contents and reduce colonic bacterial counts. Recently, studies of elective colorectal resections with primary anastomoses, with or without bowel preparation, have shown similar rates of anastomotic leak and wound infection. Despite these findings, most surgeons still prescribe bowel preparations to their patients before surgery. Bowel preparations are contraindicated in patients who require emergent intervention, have an obstruction, or have toxic colitis.

B. In the setting of severe pericolonic inflammation (e.g., in patients with UC, Crohn’s disease, or diverticulitis) or scarring (e.g., after pelvic radiation or previous abdominal surgery), the ureters may be difficult to identify intraoperatively and are vulnerable to iatrogenic injury. In such cases, preoperative placement of ureteral stents is recommended.

COMPONENTS OF THE PROCEDURE AND APPLIED ANATOMY

Preoperative Considerations

I. One dose of antibiotics, typically a second- or third-generation cephalosporin, should be administered 30 to 60 minutes before incision. If the procedure lasts longer than 4 hours, a second dose can be given.

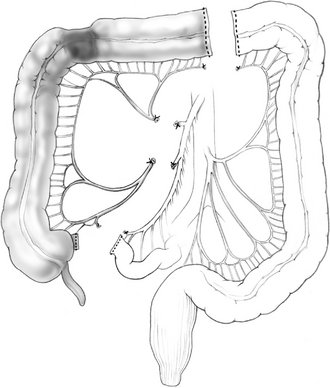

Open Right Hemicolectomy

Figure 16-1 Right hemicolectomy.

(From Cameron JL [ed]: Current Surgical Therapy, 7th ed. Philadelphia, Mosby, 2001.)

II. Incision and Exploration

III. Mobilization of the Right Colon

B. The colon is then reflected medially by dividing the white line of Toldt (the lateral reflection of the peritoneum over the mesentery of the ascending colon).

C. Care is taken to identify and remain anterior to the retroperitoneal right ureter and gonadal vessels.

IV. Division of the Bowel

A. Proximal and distal sites for division of the colon are identified. When a right hemicolectomy is performed in a patient who has cancer, the ileocolic, right colic, and right branch of the middle colic vessels are ligated. The bowel is typically divided at the terminal ileum proximally and the transverse colon to the right of the main trunk of the middle colic vessels distally; this ensures adequate vascular supply to the bowel that will be used to form an anastomosis.

V. Mesenteric Resection and Vessel Ligation

A. The mesentery of the right and proximal transverse colon is then divided in small segments to ensure vascular control.

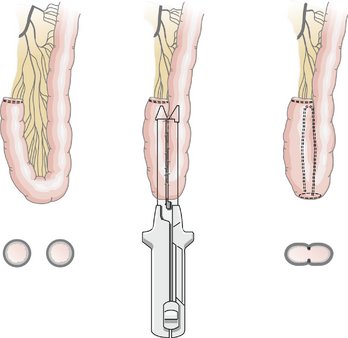

VI. Bowel Anastomosis: The anastomosis between the ileum and transverse colon can be hand sewn or stapled in an end-to-end, end-to-side, or side-to-side configuration. The stapled side-to-side approach is most often used and is discussed in detail. The hand-sewn end-to-side approach is also discussed.

A. Stapled Anastomosis

2. The divided ends of bowel are opened to permit the insertion of one jaw of a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler into each lumen.

VII. Closing the Mesenteric Defect: Closure of the defect between the ileal and transverse colon mesenteries is performed using interrupted or running sutures. Although some surgeons do not close the mesenteric defect, proponents argue that closure reduces the incidence of postoperative internal hernia formation.

Other Operative Procedures

I. An ileocolic resection is a limited resection of the terminal ileum, cecum, and appendix. Indications include ileocecal Crohn’s disease, benign lesions, and incurable cancers arising in the terminal ileum, cecum, and, occasionally, the appendix. The ileocolic vessels are ligated and divided, and a primary anastomosis is created between the distal small bowel and the ascending colon.

II. Lesions at the hepatic flexure or proximal transverse colon may require an extended right colectomy. This procedure involves the ligation and division of the middle colic vessels at their origins and resection of the majority of the transverse colon, in addition to standard right colectomy (Fig. 16-2). A primary anastomosis is created between the ileum and the distal transverse colon. After division of the middle colic vessels, the anastomosis is supplied by the marginal artery of Drummond.

III. Transverse colectomy, which involves ligation of the middle colic vessel and a right colon–left colon anastomosis, is rarely performed. In general, lesions in the transverse colon are amenable to an extended right colectomy with anastomosis of the ileum to the descending colon.

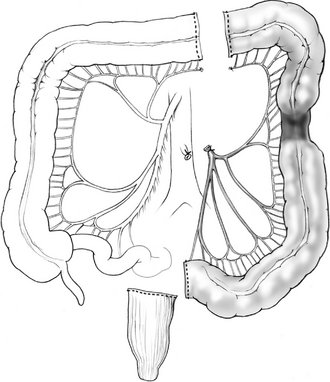

IV. Left colectomy is performed for pathology of the distal transverse colon, splenic flexure, and descending colon. The left branches of the middle colic vessel, the left colic vessel, and the first branches of the sigmoid vessels are ligated; the distal transverse and descending colon are resected; and a colocolonic anastomosis is created (Fig. 16-3).

V. Sigmoid colectomy is frequently performed for recurrent complicated sigmoid diverticulitis, and occasionally for sigmoid adenocarcinoma. Sigmoid colectomy involves ligation and division of the sigmoid branches of the inferior mesenteric artery, resection of the entire sigmoid colon, and creation of an anastomosis between the descending colon and the upper rectum (Fig. 16-4). Full mobilization of the splenic flexure is often required to create a tension-free anastomosis.

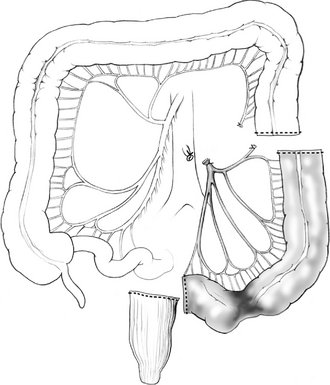

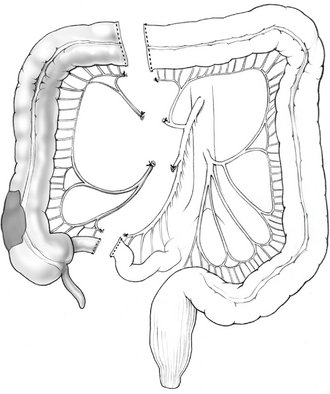

VI. Curiously, the terms “subtotal” and “total” abdominal colectomy are often used interchangeably; both describe the removal of the colon and preservation of the rectum. The ileocolic, right colic, middle colic, and inferior mesenteric vessels are ligated and divided. After colon resection, an anastomosis is created between the ileum and the upper rectum (Fig. 16-5). If an anastomosis is contraindicated, an ileostomy is created and the remaining rectum is left in place as a Hartmann’s pouch.

VII. All of these procedures can be performed using laparoscopic or laparoscopically assisted approaches. The indications for laparoscopic colon resections are essentially the same as those for the corresponding open procedures. Generally, laparoscopic approaches are associated with longer operative times, and emergent procedures should be performed using an open approach. The laparoscopic approach to right colectomy is described.

VIII. Laparoscopic Right Colectomy

B. Port placement

1. The first port is placed just above or below the umbilicus using either a “blind” percutaneous (Veress needle) or an open technique. The open technique is mandatory in pregnant patients and those who have had previous abdominal surgery.

2. After the laparoscope is inserted through the umbilical port, two additional ports are placed under laparoscopic visualization. The second port is placed in the left or right upper quadrant, 2 cm below the costal margin and lateral to the epigastric vessels. The third post is placed in the midline just above the pubis.

C. Mobilization of the colon terminal ileum, cecum, and ascending colon: Mobilization of the right colon is carried out as described for open colectomy.

D. Exteriorization, mesenteric division, and anastomosis: Division of the bowel, ligation of the mesenteric vessels, and creation of the anastomosis during a laparoscopic colectomy may be performed extracorporeally (i.e., outside of the body) or intracorporally, using endoscopic stapling devices. The extracorporeal approach is described.

1. The supraumbilical port site incision is extended transversely to the right of the umbilicus by 4 to 6 cm. Alternatively, a small midline incision may be made.

2. The cecum is delivered through this incision, and the freely mobile right colon and hepatic flexure are exteriorized.

3. Division of the bowel, resection of the mesentery, and bowel anastomosis proceed as in a standard open right colectomy.

IX. Low anterior resection is indicated for rectal lesions that are high enough to allow for adequate oncologic resection and preservation of the anal sphincters. Resection of cancers involving the lower half of the rectum should include excision of the entire mesorectum (which contains the lymph channels draining the tumor bed) in continuity with the rectum. This total mesorectal excision results in lower rates of local recurrence, impotence, and bladder dysfunction.

B. Incision

C. Mobilization and division of the bowel

1. The sigmoid colon and rectum are mobilized along the white line of Toldt from the peritoneal reflection anteriorly to the splenic flexure.

2. The ureters are identified as they course in the retroperitoneum over the internal iliac vessels.

3. The inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is identified at the base of the mesentery, and the adjacent peritoneum is incised.

7. Total mesorectal excision is performed by dissecting between the presacral fascia and the fascia propria of the rectum. The thin, avascular fibers encountered in the presacral space are often referred to as Waldeyer’s fascia.

8. The hypogastric nerves are identified at the sacral promontory. These nerves descend into the presacral space and must be preserved to maintain postoperative sexual function.

D. Creating the anastomosis

1. The proximal staple line is resected, and the “anvil” of the end-to-end anastomosis stapling device is inserted and secured in place.

X. Abdominoperineal resection is required for the management of tumors that involve the anal sphincters and sphincter preservation or are too close to the sphincters to allow for resection with adequate margins. Patients with an unfavorable body habitus or poor preoperative sphincter control may require APR as well. The abdominal portion of APR, including rectal mobilization and nerve preservation, is identical to a low anterior resection. The perineal portion of the operation involves excision of the anus, the anal sphincters, and the distal rectum through an elliptical incision that extends around the anus from the perineal body anteriorly to the coccyx posteriorly. A permanent end colostomy is brought out through the left lower aspect of the anterior abdominal wall.

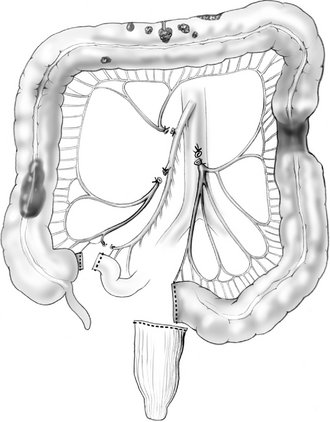

XI. Total proctocolectomy with IPAA allows for resection of the colon and rectum with restoration of GI continuity. Disadvantages of IPAA include frequent, loose bowel movements and relatively high complication rates. Notwithstanding, IPAA has become the treatment of choice in properly selected patients with UC requiring colon resection and FAP.

A. Controversy exists as to whether this operation should be performed in one stage (without ileostomy) or two (with ileostomy). The one-stage approach eliminates the need for a second operation and precludes complications that may accompany an ileostomy. Disadvantages include an increased risk of pelvic sepsis and symptomatic leaks of the pouch or ileoanal suture line. Most surgeons favor the two-stage operation, particularly in patients with UC, many of whom are immunosuppressed.

B. Ileal pouch–anal anastomosis involves mobilization of the ileal mesentery from the retroperitoneum (sometimes with division of the ileocolic artery to provide for adequate mesenteric length), rectal transection at the level of the levator muscles, and creation of an ileal pouch from the distal 20 cm of ileum (Fig. 16-6). A stapled anastomosis is constructed between the apex of the ileal pouch and the anus using an end-to-end anastomosis stapler.

POSTOPERATIVE COURSE

I. Postoperative care varies greatly, depending on the type of resection performed and the indication for surgery. Most patients are maintained on either intravenous narcotics or epidural analgesia. Oral pain medication is not initiated until the patient is tolerating oral intake. In patients without epidural analgesia, the urinary catheter can often be removed on the first postoperative day. Patients who undergo sigmoid or rectal resections are at relatively high risk for postoperative urinary retention as a result of dissection near the pelvic nerves, and may require more prolonged catheterization.

II. Twenty percent of patients who undergo elective colon resection will develop a postoperative ileus requiring the use of a nasogastric tube. Many surgeons remove the tube immediately after surgery and replace it if necessary; others advocate nasogastric decompression until the return of bowel function. Typically, a clear liquid diet is initiated with the return of bowel function and is advanced as is tolerated by the patient. Alternatively, oral intake may be initiated in the early postoperative period; however, the development of nausea and vomiting with oral intake should prompt a period of bowel rest. Antiemetics should be avoided because they may mask clinically important symptoms.

COMPLICATIONS

I. Anastomotic leak most often develops between the third and seventh days after surgery. Patients may present with vague abdominal pain, fever, or leukocytosis.

A. Most often, leaks result in contained pelvic collections in the region of the anastomosis. Rarely, significant anastomotic disruption leads to diffuse peritoneal contamination. Lastly, an enterocutaneous fistula may result when a tract develops from the site of the leak to the skin. Fistulas are sometimes associated with concomitant fluid collections.

B. The management of a leak depends on the patient’s clinical presentation. Stable patients are generally managed with bowel rest, antibiotic therapy, and percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal collections. Reoperation with intestinal diversion is an acceptable initial strategy as well. Peritonitis and clinical deterioration are indications for urgent operative intervention, which usually involves abdominal washout, drainage, and creation of a diverting ostomy. Reoperation is also necessary when fistulas do not resolve after conservative management.

II. Ureteral injury is a serious complication of colectomy and is more common when significant inflammation is present (e.g., in complicated diverticulitis). If recognized intraoperatively, the ureter should be repaired immediately. Postoperatively, patients with a ureteral injury may present with abdominal pain or fever. CT may show an intra-abdominal fluid collection. Intravenous pyelogram can be obtained to confirm the diagnosis and will show urine extravasation from the disrupted ureter. Often, a percutaneous nephrostomy tube is required for urinary diversion, followed by a delayed ureteral repair.

III. Anastomotic strictures and associated bowel obstruction can complicate colon resection. Strictures are most common after low anastomoses involving the rectum or anus. When strictures present early in the postoperative course, they are usually caused by edema at the site of anastomosis and leak. More often, strictures present weeks to months after surgery as a result of scar formation related to low-grade ischemia of the anastomosis. Symptoms may include nausea, distention, small-caliber stools, and tenesmus. Digital rectal examination (for low strictures) and sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy may aid in the diagnosis. Endoscopic dilation of the narrowed segment of bowel is sometimes an effective treatment. Strictures that are not amenable to endoscopic dilation may require operative revision of the anastomosis.