2 Cognitive and Language Evaluation

Introduction

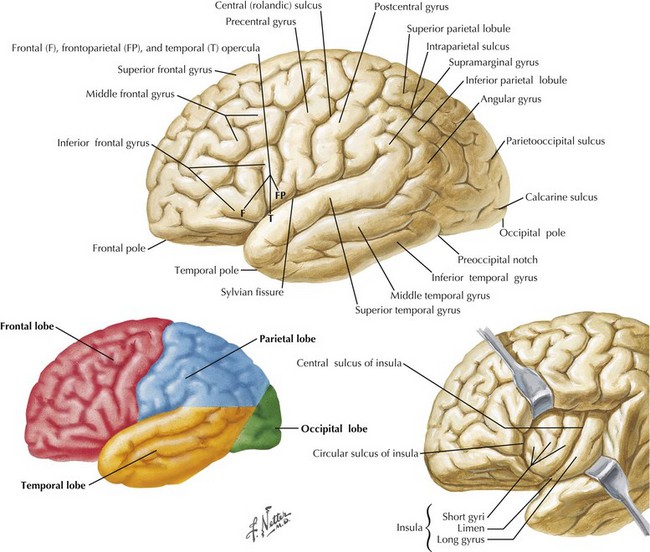

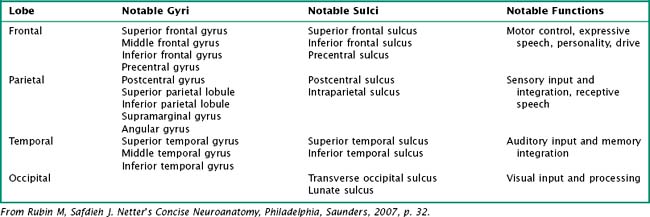

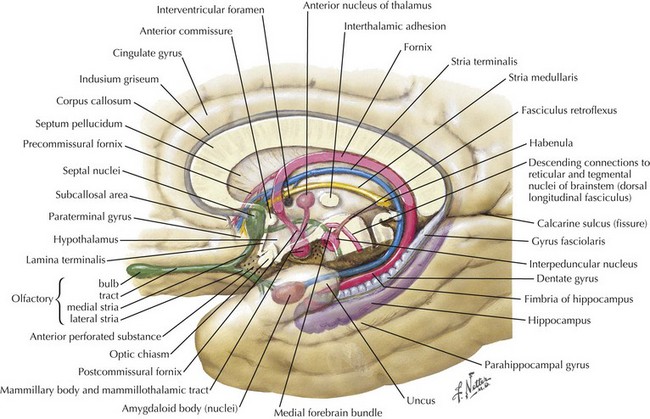

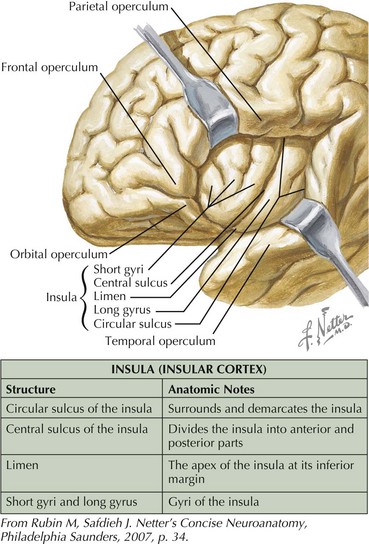

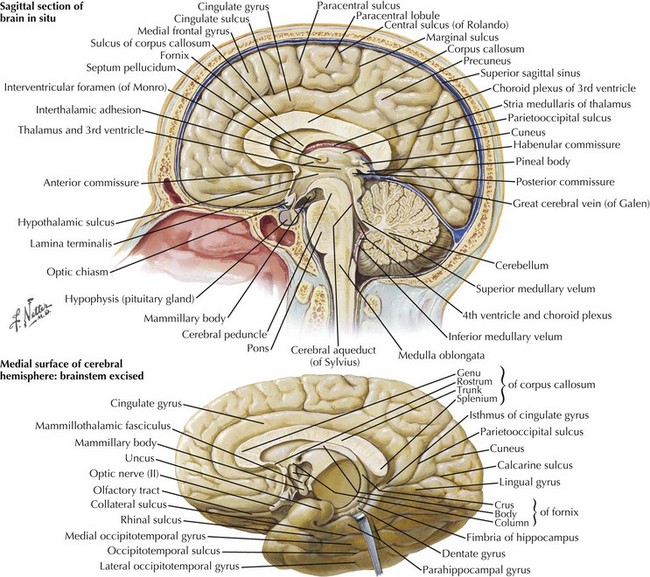

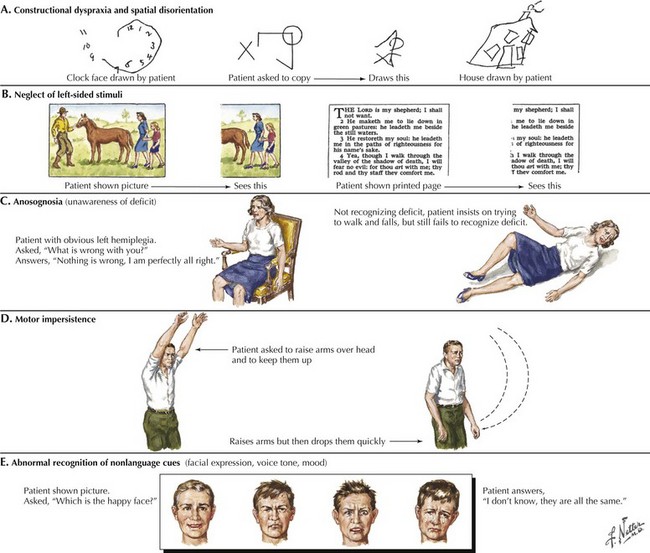

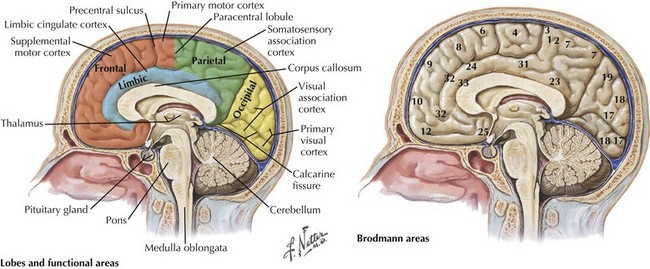

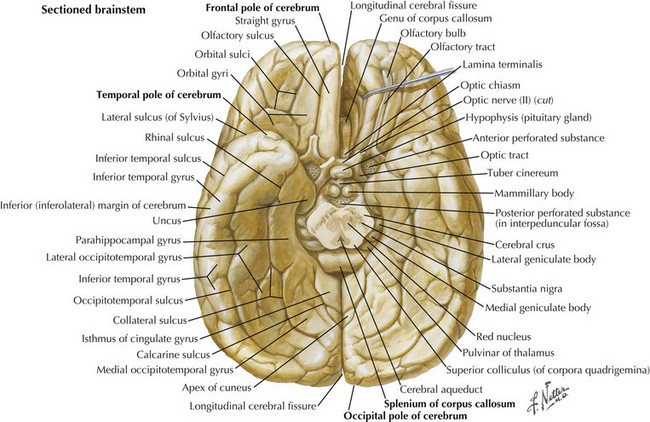

One’s direct interaction with the patient helps define the behavioral aspects of neurologic function; it is their mood, affect, level of cooperation, and distractibility that are noteworthy. The cognitive part of the neurologic evaluation strives to determine the precise level of various higher cortical functions. The human cerebral cortex, with its multiple gyri and network of many million interconnections, is the most complex part of the brain. Anatomically, the cortex is classified into four major functional areas: frontal, temporal, parietal, and occipital lobes (Fig. 2-1; Table 2-1 and Table 2-2). These anatomic substrates are carefully interconnected in a complex network. Although for the sake of discussion, these cortical areas are typically described in isolation, in reality these interconnections with other cortical and subcortical areas are critical for brain function (Fig. 2-2).

Table 2-1 Lateral Surface of the Brain: Notable Lateral Sulci

| Structure | Anatomic Significance |

|---|---|

| Lateral (Sylvian) fissure | Separates temporal lobe from frontal and parietal lobes |

| Central (Rolandic) sulcus | Separates frontal lobe from parietal lobe |

From Rubin M, Safdieh J. Netter’s Concise Neuroanatomy, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2007, p. 32.

Cognitive Testing

An Introductory Mental Status Examination

There are several standardized brief assessments of cognition, including the Mini Mental State Exam and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA). These studies are particularly useful for assessing memory problems in the elderly. The MOCA is available online at www.mocatest.org along with normative data and translation into multiple languages. It is very useful when screening for very subtle cognitive impairment as seen in Mild Cognitive Impairment or the very earliest stages of dementia. The MMSE may provide a useful tool for staging dementia severity in patients with Alzheimer disease. Additional discussion of such tests is presented in the subsequent dementia chapter (Chapter 18).

Frontal Lobe Dysfunction

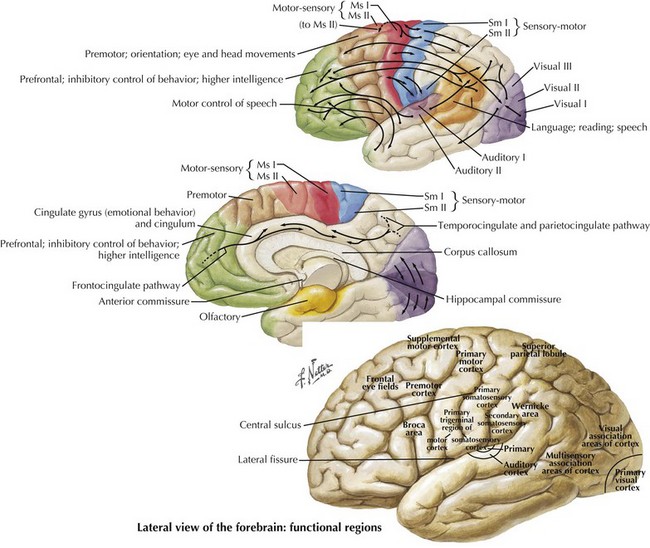

The frontal lobe comprises the major portion of the adult brain occupying approximately 30% of brain mass. This includes the motor area (Brodmann area 4), the premotor cortex (Brodmann areas 6 and 8), and significant prefrontal areas (Fig. 2-3). A Brodmann area is a region of the cortex that is defined by the organization of its cells, or cytoarchitecture, as opposed to gross anatomic landmarks such as sulci or gyri. Reference to Brodmann’s areas may provide more precise clinicoanatomic correlation and localization (see Fig. 2-3).

The significant prefrontal areas are distinct from the adjacent motor and premotor areas, particularly in their connections with other cortical areas and the thalamus (see Fig. 2-2). Most of the prefrontal–thalamic connections are made with the dorsal medial nucleus, a prime relay center for limbic projections originating from the amygdala and the basal forebrain. The reciprocal inputs are the most prominent cortical connections, originating from second-order sensory association and paralimbic association areas, including the cingulate cortex, temporal pole, and parahippocampal area. The frontal lobe is an integrator and analyzer of highly complex multimodal cortical areas, including limbically processed information.

Humans sustaining frontal lobe disorders develop significant personality changes and “release of animal instincts.” One of the earliest descriptions of frontal lobe damage described patients with apathy and disturbed emotions. Elucidation of the frontal lobe connections, particularly the medial-basal portion, demonstrates that the limbic system provides significant input to that area (Fig. 2-4). Autonomic centers originating in the brainstem and hypothalamus also have significant connections with the basal frontal lobe. When these connections are disrupted, aggressive, impulsive, and uncontrolled behavior results. Subsequent study has revealed an even greater depth and breadth of frontal lobe function.

Temporal Lobe Dysfunction

An understanding of temporal lobe anatomy helps one appreciate the various clinical deficits that can arise from lesions at this level. The temporal lobe is defined as encompassing all brain regions below the Sylvian fissure and anterior to the occipital cortex (Figs. 2-1, 2-5, 2-6). These also include subcortical structures such as the hippocampal formation, the amygdala, and limbic cortex. The temporal lobe is divided into three distinct regions: the lateral area consisting of the superior, middle, and inferior temporal gyri; the inferior temporal cortex containing the auditory and visual areas; and the medial area including the fusiform gyrus and parahippocampal gyrus.

Language

Left dominant temporal lobe injury leads to major language deficits. Wernicke aphasia is the most classic example occurring with lesions of the left superior temporal gyrus (see Fig. 2-1). Typically, these patients demonstrate spontaneous speech that is fluent with phonemic (mixed syllables) and verbal (incorrect words) paraphasic errors at times referred to as a word salad. In addition, these patients have problems with naming, comprehension, repetition, reading, and writing. There may be total lack or incomplete awareness of these various impairments. Such speech changes can be accompanied by emotional symptoms that are associated with the limbic region.

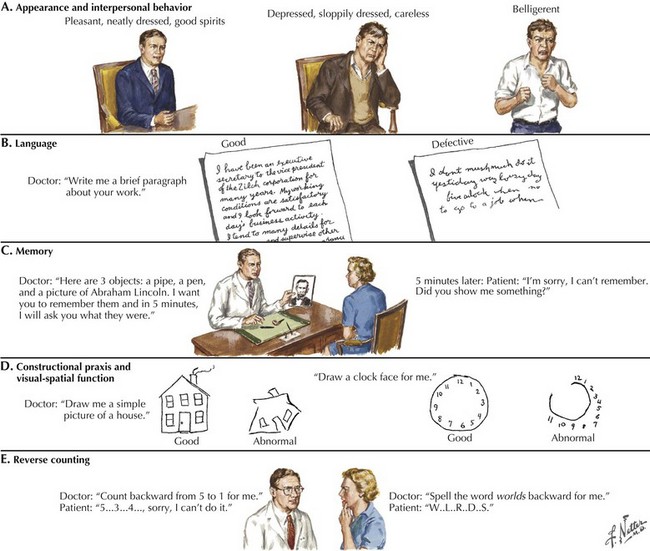

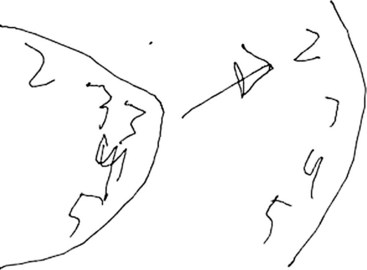

Asking the patient to provide a handwriting sample is very important in order to assess these various problems (Fig. 2-7). Damage to the left temporal region may result in wider right-side margins, spaces, or wide separations between letters or syllables and disrupt the continuity of the writing line. Patients with damage to the left temporal region may also be noted to have a decline in ability to write in script, as opposed to a better-preserved ability to print.

The clock-drawing test that was used to identify frontal lobe deficits is also useful in identifying temporal lobe deficits (see Fig. 2-7). In order to draw a clock, there must be a mental visual representation of what features are essential. Visuospatial abilities are essential to determining the layout and proportions, and for making sure that features are accurate on both sides of space. Visuospatial perception is also a component of evaluating the output and making corrections.

Parietal Lobe Dysfunction

The parietal lobe is situated between the frontal and occipital lobes. The central sulcus separates frontal from parietal cortex, while the parietooccipital sulcus separates parietal from occipital cortex (see Fig. 2-1). The Sylvian fissure forms the lateral boundary separating parietal from temporal cortex. The most anterior portion of the parietal lobe, sitting immediately behind the central sulcus, is the primary somatosensory cortex (Brodmann area 3; see Fig. 2-3). More posteriorly, the parietal lobe may be divided into the superior parietal lobule (Brodmann areas 5 and 7) and the inferior parietal lobule (Brodmann areas 39 and 40) (see Fig. 2-3). These areas are separated by the intraparietal sulcus.

Somatosensory integration begins in the primary somatosensory cortex, where basic tactile localization is appreciated. This is evaluated by testing both joint position and two-point discrimination sensory modalities. Once sensory information is received in the primary somatosensory cortex, this then streams posteriorly toward the somatosensory association cortex (see Fig. 2-2). Here, tactile information is integrated to provide discriminatory sensation over larger areas of the body surface for sensory definition of object weight, size and shape, texture, etc. This allows for specialized tactile sensation, such as graphesthesia and stereognosis. Most importantly, this allows the integrative mapping of the spatial, tactile, and visual aspects of one’s body. The sensory mapping of the external world takes place posteriorly in the parietal lobe. There are two “functional maps,” one of the self and the other of the world. These are also integrated, presumably in the heteromodal association area in the right parietotemporal–occipital junction.

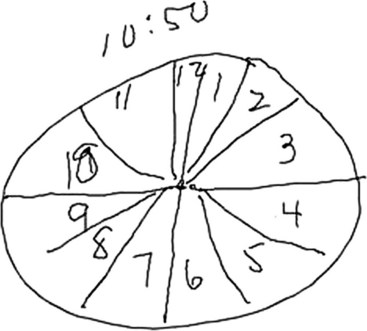

Right Parietal Lobe

A related condition, called asomatognosia, involves the patient’s inability to recognize his own body part. When viewing his own hand, the patient does not recognize it as his own. Moreover, he may misidentify it as someone else’s limb. Anosognosia refers to the patient’s absent recognition of illness or disability, which is not mediated by psychological denial and is not associated with a disturbance of mood (Fig. 2-8). A milder version of neglect may occur while writing or drawing. The patient may draw a clock and place all the numbers and even the hands within the right hemispace of the clock face. Visuospatial impairment is relatively common following right parietal lesions. This may be seen on construction tests, where the patient is asked to copy shapes, such as a clock, a cube, or overlapping geometric figures (see Fig. 2-7).

Occipital Lobe Dysfunction

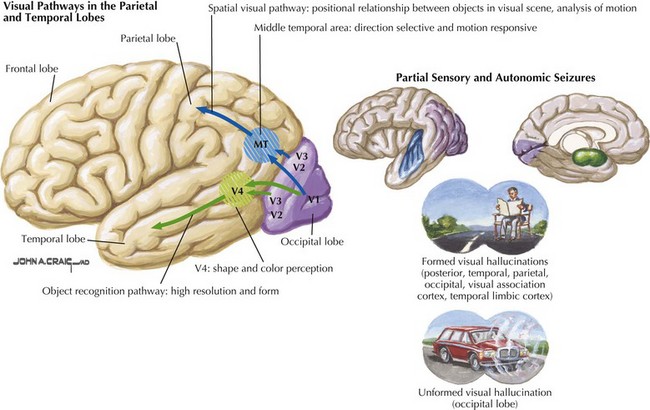

The primary function of the occipital cortex is to process and organize visual information. The calcarine area, Brodmann area 17 (Figs. 2-9 to 2-11; Table 2-3), represents the primary visual cortex. It is located within the medial side of the occipital cortex along the calcarine sulcus. This region is also called the striate cortex because of prominent myelin striation, called the Stria of Gennari. The portion of the occipital cortex that lies beyond the primary visual area is termed extra-striate cortex; it subserves higher order visual processing, including color discrimination, motion perception, shape detection, etc. Each visual area contains a full map of the mentally perceived visual world.

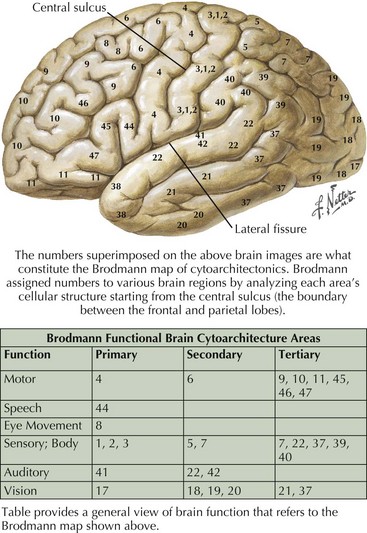

| Cortical Structures | ||

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Anatomic Notes | Functional Significance |

| Frontal pole | Anterior-most portion of frontal lobe | Vulnerable to injury during head trauma |

| Straight gyrus (gyrus rectus) | Most medial and inferior gyrus of frontal lobe | |

| Olfactory sulcus | Separates straight gyrus from more lateral orbital gyri | Olfactory tract travels with this sulcus |

| Orbital gyri and sulci | Form the floor of frontal lobes; rest on the roof of orbits | |

| Temporal pole | Anterior-most portion of temporal lobe | Vulnerable to injury during head trauma |

| Uncus | Medial-most bulb-shaped projection of temporal lobe | If swollen may compress the ipsilateral midbrain, causing contralateral hemiparesis |

| Parahippocampal gyrus | Large inferomedial temporal lobe gyrus | Involved in emotion as part of the limbic system |

| Collateral sulcus | Separates parahippocampal gyrus from medial occipitotemporal gyrus | |

| Medial occipitotemporal gyrus | Lies lateral to parahippocampal gyrus | |

| Occipitotemporal sulcus | Separates medial and lateral occipitotemporal gyri | |

| Lateral occipitotemporal gyrus | Forms inferolateral border of temporal lobe; contiguous with inferior temporal gyrus | |

| Occipital pole | Posterior-most portion of the occipital lobe | Vulnerable to injury during head trauma |

From Rubin M, Safdieh J. Netter’s Concise Neuroanatomy, Philadelphia, Saunders, 2007, p. 37.

The primary visual cortex provides a low-level description of visual object shape, spatial distribution, and color properties. Projections from the extra-striate cortex branch ventrally toward temporal lobes and dorsally toward parietal lobes. The visual information from the ventral stream integrates with temporal lobe association areas to allow recognition of objects, people, and places. Visual information travelling through the dorsal stream merges with parietal association areas to allow proper visual orientation of objects in the environment and of the self within the environment (see Fig. 2-2). There are few cognitive syndromes attributable to disorders placing the occipital lobe in isolation.

Pure alexia without agraphia is a disconnection syndrome that occurs when a lesion within the left occipital lobe extends to involve fibers traversing across the splenium of the corpus callosum from the right occipital lobe (see Fig. 2-10). This process causes loss of the ability to read while sparing all other language function. All cases include a right homonymous hemianopsia (hemifield cut). Visual information recorded by either or both occipital lobes must be directed to the posterior left temporal lobe per se in order for the individual to detect and process the visual symbols of language. Therefore, the combined left occipital lobe and splenium lesion effectively blocks data—perceived in the left visual field and recorded in the right occipital lobe—from being sent to the contralateral dominant temporal lobe. Thus, even though such individuals can see objects in their left hemifield, utilizing their still intact right occipital lobe, all vision from this cortex effectively has a conduction block vis-à-vis the precise act of reading. This is because any visual symbols of language are no longer being transmitted through the splenium and thus do not reach the dominant language areas. In essence, this lesion disconnects the right visual cortex visual information from reaching the contralateral language, and writing centers. Although the left hemifield remains intact, its potential language information cannot be “seen” by the dominant left temporal lobe. In effect, this condition could also be called pure word blindness.

In summary, the clinician may use a variety of higher cortical function assessment modalities to evaluate patients with primary cerebral cortex disorders. Some common examples of these methods are outlined in Figure 2-7.

Cerebellum

Aphasia

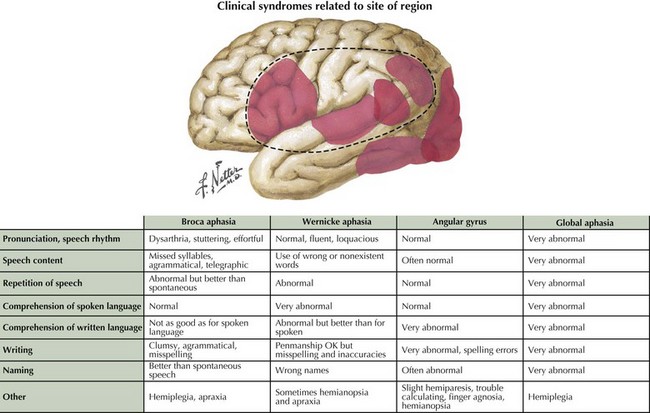

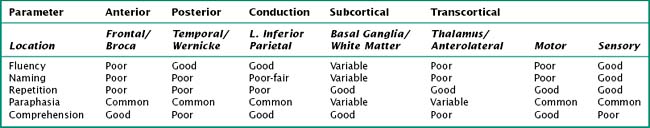

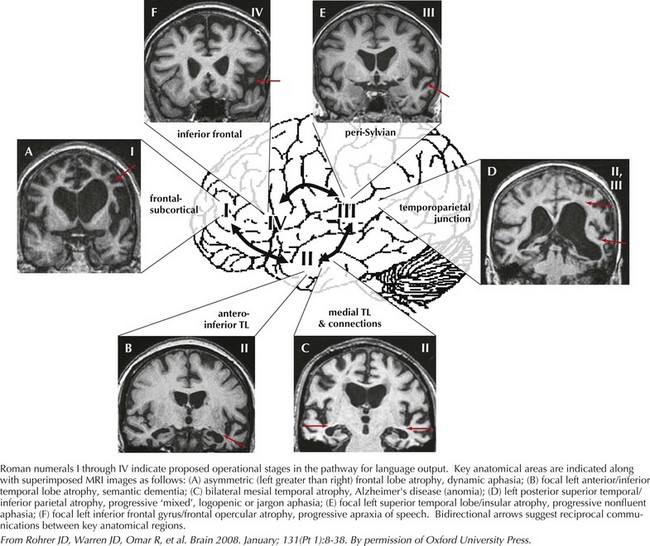

Language encompasses multiple cortical regions and is not classifiable within strict cortical anatomic borders. Impairment of language function is a common neurologic symptom presenting acutely, as in stroke, or more insidiously, as in primary progressive aphasia. The classic nomenclature of the aphasia syndromes is largely based on lesion analysis in cases of stroke or tumor. These syndromes postulate distinct cortical regions responsible for the various phases of language processing from comprehension to expression. Broca syndrome is characterized by stuttering, agrammatical, effortful, and telegraphic language. This was thought to be an expressive language disorder typical of anterior frontal lesions (so-called motor aphasia). Wernicke aphasia, typified as a receptive comprehension language disorder, is characterized by the fluent expression of wrong or nonexistent words and syllables that is sometimes referred to as a word salad. Receptive language disorders were thought to be related to lesions of the more posterior temporal parietal cortex (Fig. 2-12).

Often, patients with aphasia present to the neurologist complaining of word-finding difficulty; this is a broad-based symptom that is not always the result of a primary language disorder. Rather, it may be a manifestation of either inattention or a memory impairment. Therefore, the assessment of language must distinguish primary language disorders from other cognitive deficits, that is, secondary word-finding impairment. The patient presenting with progressive primary language disturbance often does not fit neatly into the traditional neuroanatomic aphasia classifications (Table 2-4). Therefore, further discussion of language assessment will not focus on the traditional bedside aphasia exam, namely, tests of fluency, comprehension, naming, repetition, writing, and reading. Rather, we will review newer techniques for the examination of language elucidated through study of patients with primary progressive aphasia (Fig. 2-13).

The most important aspect of language assessment is carefully listening to conversational language during the patient interview. If the patient is not very talkative, the examiner may present him or her with a picture to describe. Further tests of naming, repetition, writing, and reading all provide additional important information. In the case of progressive aphasia, the nature of language disturbance may have significant implication in identifying the underlying neurodegenerative disease. Indeed, assessment of language in this way has proven utility in localizing cortical regions attributed to various primary progressive aphasic syndromes (see Fig. 2-13). This approach elaborates on the classic aphasia exam, providing a better understanding of language processing and improving localization during examination.

Benson DF. Aphasia, Alexia, and Agraphia. New York: Churchill Livingstone Inc.; 1979.

Carey BHM. An Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82. New York Times Obituaries; December 4, 2008.

Feinberg TE, Farrah MJ. Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 1997.

Freedman M, Leech L, Kaplan E, et al. Clock Drawing: A Neuropsychological Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1994.

Goodglass H, Kaplan E. The Assessment of Aphasia and Related Disorders, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1983.

Heilman KM, Valenstein E. Clinical Neuropsychology, 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2003.

Jeffrey P, Nussbaum PD. Clinical Neuropsychology: A pocket handbook for assessment. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1998.

Kalashnikova LA, Zueva YV, Pugacheva OV, et al. Cognitive impairments in cerebellar infarcts. Neuroscience and Behavioral Physiology. 2005;35(8):773-779.

Kaplan E. Right hemisphere contributions to reading: horse and elephant example. Personal communication; 2000.

Kolb B, Whishaw IQ. Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology, 6th ed. New York, NY: Worth Publishers; 2008.

Kolb B, Whishaw IQ. Fundamentals of Human Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Worth Publishers; 2003.

Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW. Neuropsychological Assessment Fourth Edition. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2004.

Mesulam MM. Principles of Behavioral Neurology. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 1985.

Rawlinson G. The Significance of Letter Position in Word Recognition. PhD Thesis, Nottingham University http://web.archive.org/web/20080117213646/http://www.mrc-cbu.cam.ac.uk/~mattd/Cmabrigde/rawlinson.html, 1976.

Rizzo M, Eslinger PE. Principles and Practice of Behavioral Neurology and Neuropsychology. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004.

Rohrer JD, Knight WD, Warren JE, et al. Word-finding difficulty: a clinical analysis of the progressive aphasias. Brain. 2008;131(pt 1):8-38.

Schmahmann JD, Sherman JC. The cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Brain. 1998;121:561-579.

Schmahmann JD. Disorders of the cerebellum: Ataxia, dysmetria of thought, and the cerebellar cognitive affective syndrome. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience. 2004;16(3):367-378.

Schmahmann JD, Weilburg JB, Sherman JC. The neuropsychiatry of the cerebellum—insights from the clinic. The Cerebellum. 2007;6:254-267.

Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests Third Edition. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2006.

Strub RL, Black FW. The Mental Status Examination in Neurology. Philadelphia: FA Davis; 2000.