CHAPTER 108 Clinical Features

Neurology of Brain Tumor and Paraneoplastic Disorders

This chapter focuses on three subjects: the pathogenesis of signs and symptoms of brain tumors, the clinical presentation of patients with brain tumors, and the spectrum of central nervous system diseases usually included under the rubric of paraneoplastic neurological disorders. This review is necessarily brief. For a more in-depth treatment of the clinical presentation of brain tumors, see Shapiro and colleagues’ article.1 For the paraneoplastic disorders, see the paper by Darnell and Posner.2

Pathophysiology of Signs and Symptoms Associated with Brain Tumors

Generalized symptoms from brain tumors are manifestations of increased intracranial pressure, a result of the expanding tumor volume and the associated edema. Tumors may obstruct the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pathways, producing hydrocephalus. As the mass enlarges, intracranial pressure rises; brain tissue may be displaced through the rigid intracranial dural passageways, producing various herniation syndromes. Cerebral dysfunction and headache ensues. Abrupt headache and worsening neurological signs may accompany sudden increases in intracranial pressure that last 5 to 20 minutes. These episodes of raised pressure have a characteristic appearance on recording of intracranial pressure leading to their name, plateau waves.3

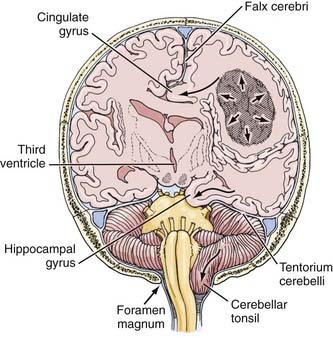

The herniation syndromes are life-threatening. Because the skull is divided into compartments by the relatively inelastic dura, an expanding mass in one compartment forces brain tissue through the openings between compartments, tearing blood vessels and compressing the neuropil (Fig. 108-1).4 A unilateral cerebral mass may force the medial surface of the brain beneath the falx cerebri (cingulate herniation). Transtentorial and tonsillar herniation may occur because of displacement of brain tissue through, respectively, the tentorial notch and foramen magnum. Table 108-1 lists the pathogenesis and clinical manifestations of the herniation syndromes.4

| PATHOGENESIS | CLINICAL MANIFESTATION |

|---|---|

| CENTRAL HERNIATION | |

| Lateral and Forward Shift of Diencephalon and Upper Midbrain | |

| Diencephalic compression | Decreased state of consciousness, small pupils, Cheyne-Stokes respiration |

| Midbrain pontine compression | |

Adapted from Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff N, Plum F. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Cerebral edema accompanies growing brain tumors. It is produced mostly within a parenchymal brain tumor but also comes from the surrounding brain tissue as a result of the release of vasogenic permeability factors produced by the tumor, which act on brain capillaries.5 (The vascular permeability factor has been identified as vascular endothelial growth factor, which plays an important role in angiogenesis of tumors.6) Cerebral edema increases the total size of the mass. It is not unusual for a tumor of perhaps 20 g to produce a mass of nearly 100 mL because of the associated edema. Cerebral edema may also be produced by an extra-axial tumor, in which case the edema, also vasogenic in origin, comes only from the brain tissue itself.

Clinical Manifestations of Intracranial Tumors

General Manifestations

Mental Changes

Mental changes are a frequent general clinical manifestation of intracranial tumor (Table 108-2). They are often subtle in presentation and onset and may not attract the attention of friends and family members until the patient’s behavior becomes abnormal. Psychomotor retardation is the most common mental change accompanying a brain tumor. Characteristically, impersistence in routine tasks, emotional lability, inertia, faulty insight and forgetfulness, reduction in the range of mental activity, indifference to social practices, reduced initiative and spontaneity, and blunted affect are seen. Patients may sleep for longer periods, complaining that they seem unable to get through a day without taking a nap. Frank confusional states and dementia usually occur later and are more likely to accompany focal signs of brain disease. Alternatively, the change in the state of consciousness may progress to stupor and frank coma. Changes in personality may be described in “psychological terms”: depression, euphoria, impulsive behavior.7 In my series, almost 20% of patients have, at one time or another, sought psychological help for symptoms that, in retrospect, were clearly related to the tumor. Mental changes must be viewed together with other signs and symptoms, and especially with a history of progression of symptoms, to lead the physician to suspect a neoplastic process.

| PSYCSHOMOTOR RETARDATION |

Headache

Headache occurs in about 50% of patients with brain tumor at some time during the course of the illness.8 Headache is more prominent and tends to occur earlier when the tumor produces increased intracranial pressure. Of special importance is a headache that has recently changed in character, for example, becoming more intense, frequent, or longer lasting. Although classic brain tumor–associated headaches are severe, often worse in the morning, all brain tumor patients do not have morning headaches, and in fact may have head pain at any time of day or night.8 The head pain from brain tumor is often intermittent and may be described as deep, aching, or pressure-like rather than the more characteristic throbbing pain of migraine. It is often aggravated by the Valsalva maneuver, as in coughing or straining, and frequently becomes worse through change of posture. The headache that occurs in the early morning hours appears to be related to the recumbent posture and is thought to be associated with increased intracranial pressure as a result of lying down.

Generalized Convulsions

Seizures occurring for the first time in adults are more likely to be due to focal cerebral disease, especially neoplasms, than are seizures that begin in childhood, which are more often part of the epilepsies that are characteristic of this age group.9 Intracranial tumors produce both generalized major motor convulsions and various forms of focal seizures. Petit mal epilepsy is probably never due to a neoplasm, but minor temporal lobe seizures (partial simple or complex) that resemble petit mal attacks may accompany temporal lobe tumors. Jacksonian seizures that progress from one body part to another usually imply a lesion of the motor or sensory cortex. Lesions of the temporal lobe characteristically give rise to partial complex (psychomotor) seizures that may be associated with olfactory hallucinations (uncinate fits), disorders of visual or auditory perception, episodes of déjà vu, or automatic behavior.

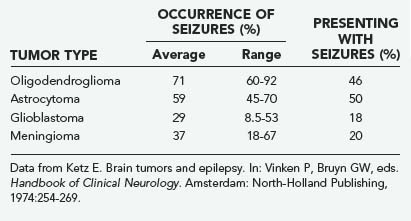

Seizures, both generalized and focal, occur in 25% to 50% of patients with cerebral tumors (Table 108-3).10 They are more likely to accompany slowly growing tumors than they are the more rapidly growing malignant neoplasms.11 A review of data of the Brain Tumor Cooperative Group (BTCG) database revealed that seizures occurred as the initial manifestation of tumor in 50% of patients with anaplastic astrocytoma but in only 27% of patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Seizures have been reported to occur in 25% of patients with reported malignant gliomas.12 Low-grade astrocytomas and oligodendrogliomas are more likely to present as seizures than are other tumors; indeed, a single seizure is now the most common presentation of a patient with a low-grade glioma diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A syndrome of low-grade gliomas as a cause of chronic epilepsy has been recognized.13 Generalized seizures may occur with tumors in a variety of locations, whereas focal seizures are more common with tumors in the motor or sensory subcortical regions. Partial complex seizures are much more frequent with tumors of the temporal lobe than tumors located elsewhere in the brain. Seizures infrequently accompany infratentorial childhood brain tumors but occur in 22% of children younger than 14 years with supratentorial tumors and 68% of older teenagers with such tumors.14

Papilledema

Papilledema consists of swelling of the optic nerve head with engorgement of the retinal veins; it may be accompanied by hemorrhages into the nerve and adjacent retina. Its presence almost always indicates raised intracranial pressure. In the older literature, papilledema was a frequent finding in patients with brain tumors. Thus, Huber15 reported that of his 1166 patients with brain tumor, 59% had papilledema, and 41% did not. In recent years, the overall incidence of papilledema in patients with brain tumor has decreased; currently, fewer than 20% of such patients have papilledema, although it is more common with increased intracranial pressure.8 The reduced incidence appears to be related to earlier diagnosis, the initiation of corticosteroid hormones to control raised intracranial pressure, and the earlier specific therapy of the tumors.

Focal Manifestations of Intracranial Tumor

Focal clinical manifestations of intracranial tumor depend on which regions of nervous system are impaired and, by definition, vary with the location of the process (Table 108-4). Focal seizures may accompany tumor invasion of the cortex. A jacksonian seizure is most likely to occur with central-parietal tumors, whereas partial complex (psychomotor) seizures are usually associated with temporal lobe tumors.

TABLE 108-4 Focal Signs and Symptoms Accompanying Brain Tumors and Their Localization

| SYMPTOMS AND SIGNS | LOCALIZATION |

|---|---|

Frontal Lobe Tumor

The disorders associated with frontal lobe lesions include intellectual impairment, impairment of initiative and spontaneity, personality changes, and motor disturbances. The disturbances may be sufficiently serious that they may predict survival after treatment.16

Personality Changes

Two types of personality changes may accompany a frontal lobe lesion: apathetic and indifferent (pseudodepressed) and euphoric (pseudopsychopathic).17 Admixtures of the two are more common than the pure types. The passive, submissive patient fits into the apathetic picture. Pseudopsychopathic patients vary from those whose humor becomes inappropriate, such as making silly jokes (witzelsucht), to those who exhibit socially unacceptable behavior, such as disrobing or urinating in public. Although these dramatic examples do occur, by far the most common personality change is one of disinterest, inattentiveness, impersistence, and sometimes drowsiness. There are almost always accompanying motor disturbances.

Temporal Lobe Tumor

Temporal lobe tumors, particularly in the nondominant hemisphere, are often relatively “silent” except when they cause seizures. The latter tend to be of the partial complex (psychomotor) variety.9 Seizures originating from the temporal lobe may include a variety of formed visual images (e.g., colored pinwheels, flashing lights) or visual hallucinations of complex formed images. Seizures from lesions in the hippocampal gyrus may include odd, often unpleasant odors as part of the aura—so-called uncinate fits. Tumors involving the surface of the dominant temporal lobe produce mixed expressive and receptive aphasia or dysphasia, chiefly anomia.

Pituitary and Suprasellar Tumor

Pituitary and suprasellar tumors produce neurological and endocrinologic abnormalities. Pituitary adenomas may present as intrasellar secretory or nonsecretory masses, or masses with extrasellar extension. Secretory adenomas produce hormones that cause specific endocrinopathies. Enlarging pituitary adenomas cause headache; as the tumor grows out of the sella, it compresses the optic chiasm, nerve, or tracts, as well as the hypothalamus. The most common visual field defect is bitemporal hemianopia, but unilateral optic atrophy, contralateral hemianopia, or any combination of the three may occur. Hypothalamic compression usually causes diabetes insipidus from injury to the supraoptic-pituitary tract. The tumor may destroy functioning glandular tissue and cause pituitary deficiency. Occasionally, acute degeneration (hemorrhage or infarction) of a pituitary tumor produces pituitary apoplexy, the syndrome of sudden headache, amblyopia, diplopia, drowsiness, confusion, or coma.18

Karnofsky Performance Score

The clinical symptoms and signs reviewed alert the physician to the possibility of brain tumor and offer clues to its localization. The same clinical features may be used to follow the patients during treatment and may be combined to semiquantify their quality of life. In the early days of cancer chemotherapy, Karnofsky and Burchenal established criteria for patients’ performance status as one measure of the outcome of treatment.19 The Karnofsky performance score (KPS) quickly became a standardized tool for expressing such outcome and was adapted for brain tumor treatment studies. The KPS is a 10-grade scale describing the patient’s capabilities (Table 108-5). KPS scores of 80 to 100 apply to patients who can work or maintain a home. KPS scores of 50 to 70 apply to patients whose clinical status prevents them from working. KPS scores of 40 and below apply to patients who are disabled. A number of quality-of-life instruments have since been tested, adapted for brain tumors, and compared with the KPS.20–22 Nevertheless, the KPS remains a mainstay of brain tumor studies.

TABLE 108-5 Karnofsky Performance Score for Brain Tumor Patients

| SCORE | PATIENT STATUS |

|---|---|

| 100 | Normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease |

| 90 | Able to carry on normal activity, minor symptoms |

| 80 | Normal activity with effort, some symptoms |

| 70 | Cares for self, unable to carry on normal activity |

| 60 | Requires occasional assistance, cares for most needs |

| 50 | Requires considerable assistance and frequent care |

| 40 | Disabled, requires special care and assistance |

| 30 | Severely disabled, hospitalized, death not imminent |

| 20 | Very sick, active supportive treatment needed |

| 10 | Moribund, fatal processes are rapidly progressing |

Paraneoplastic Disorders

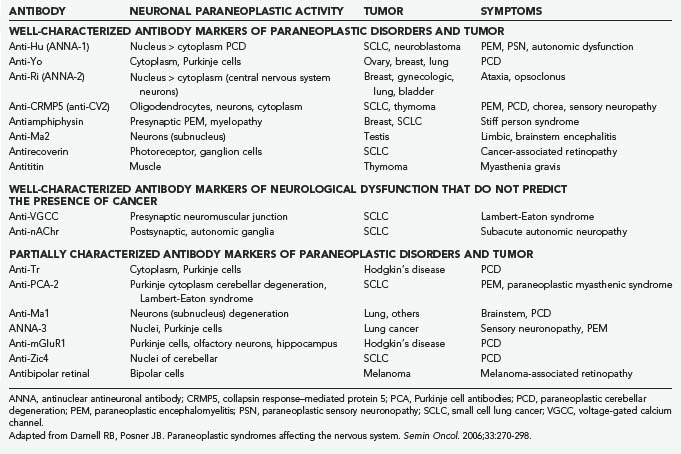

The paraneoplastic neurological disorders consist of a diverse group of syndromes affecting the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system, muscle, and neuromuscular junctions that occur in patients with cancer but are not caused by direct invasion of the cancer into the nervous system.2 The cause of these disorders has not been proved, although much evidence suggests an immunologic connection for many if not most of them. Thus, a number of antibodies have been found in the serum (and sometimes the CSF) of affected patients that react with internal neuronal antibodies (Table 108-6). Specific antigens have been identified for some of the antibodies, and for some, the gene defect has also been determined. Paraneoplastic neurological disorders are rare diseases, although their identification depends on the vigor with which a diagnosis is pursued. The associated cancers are often small at the onset of the neurological disorder and span the range of the common tumors, including small cell lung cancer, ovarian and breast cancer, and the lymphomas. However, within each category of cancer, the incidence of paraneoplastic disorder is still rare, especially for the specific disorders, such as paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. The incidence rises if one considers the nonspecific disorders such as sensorimotor peripheral neuropathy, which may accompany the cachexia of advanced cancer. Moreover, several of the specific disorders may occur in the absence of cancer.

Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration

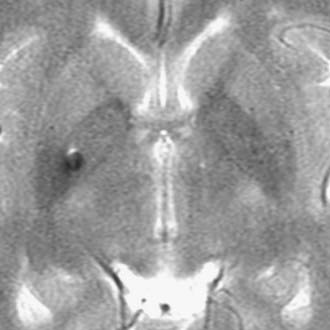

Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration (PCD) is the best characterized of these disorders. It may be associated with small cell lung cancer, ovarian or uterine cancer, and lymphomas. PCD presents well before the cancer is found, often as long as months to a year. A specific syndrome was first described in patients with breast, ovarian, or uterine cancer in which PCD was associated with a circulating autoantibody, designated anti-Yo, that reacts with Purkinje cell cytoplasm. Pathologically, the cerebellum is devoid of Purkinje cells. The anti-Yo antibody reacts with two antigens that are found in the Purkinje cells and in the tumors.23 PCD has been found in association with other antibodies designated anti-Hu and anti-Ri, although the clinical findings and tumors differ. Clinically, PCD begins with a gait disorder, progressing over weeks to months to involve most cerebellar functions and eventually producing severe dysarthria and dysmetria, associated with diplopia and vertigo. The disease then stabilizes at a point where the patient is totally disabled. Pleocytosis may be present in the CSF, and cerebellar atrophy is seen on MRI. Treatment directed at the cerebellar disorder is ineffective, and successful treatment of the cancer does not improve the neurological disorder.

Limbic Encephalitis and Encephalomyelitis

Limbic encephalitis is an inflammatory process mostly confined to the limbic system; it is a rare complication of cancer, most commonly small cell lung cancer.23,24 The patient develops a severe amnestic syndrome over days to weeks, in association with personality change, agitation, confusion, and seizures. The CSF is usually inflammatory. MRI reveals medial temporal lobe fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) or T2-weighted hyperintensity. The disease may include other areas of the brain (brainstem encephalitis) and spinal cord. Anti-Hu antibody may be identified, and as noted later, a sensory neuronopathy may also occur. Other antibodies may also occur (see Table 108-6). The tumors associated with encephalitis include small cell lung cancer, testicular germ cell neoplasms, thymoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and teratoma. Treatment of tumor may be associated with improvement in the neurological disorder. However, the disorder also occurs in the absence of tumor and may respond to immunologic therapies.

Subacute Sensory Neuronopathy

Subacute sensory neuronopathy clinically presents as severe sensory ataxia of subacute onset; all sensory modalities are affected. There is inflammation of the dorsal root ganglia. When associated with cancer, the tumor is usually small cell lung cancer. The combination of sensory neuronopathy and encephalomyelitis in patients with small cell lung cancer has been described in association with the presence of anti-Hu antibody (see Table 108-6).2 Most of the patients are women.

Opsoclonus and Myoclonus

Opsoclonus consists of arrhythmic, multidirectional, high-amplitude conjugate saccades and is often associated with diffuse or focal myoclonus and truncal titubation, with or without other cerebellar signs.2 The condition was first described in children in whom about 50% harbor neuroblastomas; however, opsoclonus-myoclonus can also occur with infections and toxic metabolic disorders. The syndrome occurs rarely in adults, of which some are paraneoplastic, usually associated with lung cancer.25 A small number of woman with breast or ovarian cancer have been described with brainstem and cerebellar dysfunction who harbor anti-Ri antibody; they may have opsoclonus-myoclonus as well.

Lambert-Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome

Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome is the most common of the paraneoplastic disorders, with an incidence of up to 6% in patients with small cell lung cancer.2 It resembles myasthenia gravis in that weakness is a function of defective transmission at the neuromuscular junction. It differs from myasthenia gravis in that the pathogenesis involves reduced release of acetylcholine from presynaptic terminals rather than reduced postsynaptic receptor numbers. The bulbar muscles are not usually involved as they are in myasthenia gravis, and in fact power may actually increase with effort. Electromyography reveals a decrement of the compound muscle action potentials after low-frequency repetitive nerve stimulation and an increment after high-frequency stimulation. The patients appear to have an autoantibody that binds specifically to voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) of the presynaptic neuromuscular junction. Patients usually present with proximal leg weakness, impotence in men, and dry mouth with a metallic taste in both men and women. Symptoms may improve after plasmapheresis or immunosuppression, supporting the notion that the illness is humorally mediated. Treatments that increase transmitter release may also improve the weakness; 3,4-diaminopyridine appears to be particularly effective.

Polymyositis and Dermatomyositis

Of the inflammatory myopathies, dermatomyositis, polymyositis, and inclusion body myositis, only the first is considered a paraneoplastic disorder, with an associated risk for cancer in up to 22% of patients.2 The risk for cancer in patients with polymyositis is only slightly higher than for the general population, and that for inclusion body myositis even lower. The myopathy involves proximal weakness, more in the legs than arms; the muscles may be painful and mildly tender. Weakness of pharyngeal muscles causes dysphagia and possibly aspiration. The serum creatine kinase is elevated up to 10 times the normal value, and the electromyogram demonstrates findings of myopathy. Inflammatory myopathy is seen on biopsy. The rash of dermatomyositis is most commonly diffusely erythematous over the chest and shoulders in a V-shaped distribution. A minority of patients also have a red-violet heliotrope rash over the upper eyelids. The disease is treated with immunosuppression.

Bartolomei JC, Christopher S, Vives K, et al. Low-grade gliomas of chronic epilepsy: a distinct clinical and pathological entity. J Neurooncol. 1997;34:79-84.

Bataller L, Graus F, Saiz A, Vilchez JJ. Clinical outcome in adult onset idiopathic or paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus. Brain. 2001;124:437-443.

Blumer D, Benson DF. Personality changes with frontal and temporal lobe lesions. In: Benson DF, Blumer D, editors. Psychiatric Aspects of Neurologic Disease. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1975:151-170.

Cardosa ER, Peterson EW. Pituitary apoplexy: a review. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:363-373.

Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:327-340.

Darnell RB, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic syndromes affecting the nervous system. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:270-298.

Forsyth PA, Posner JB. Headaches in patients with brain tumors: a study of 111 patients. Neurology. 1993;43:1678-1683.

Gilles FH, Sobel E, Leviton A, et al. Epidemiology of seizures in children with brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1992;12:53-68.

Gultekin SH, Rosenfeld MR, Voltz R, et al. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain. 2000;123:1481-1494.

Huber A. Eye Symptoms in Brain Tumors. St. Louis: CV Mosby Co.; 1971. 86-155

Hughes JR, Zak SM. EEG and clinical changes in patients with chronic seizures associated with slowly growing brain tumors. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:540-543.

Karnofsky DA, Burchenal J. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

Ketz E. Brain tumors and epilepsy. In: Vinken P, Bruyn GW, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing; 1974:254-269.

Mackworth N, Fobair P, Prados MD. Quality of life self-reports from 200 brain tumor patients: comparisons with Karnofsky performance scores. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:243-253.

Meyers CA, Hess KR, Yung WK, Levin VA. Cognitive function as a predictor of survival in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:646-650.

Moots PL, Maciunas RJ, Eisert DR, et al. The course of seizure disorders in patients with malignant gliomas. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:717-724.

Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, et al. The Karnofsky performance status scale: an examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984;53:2002-2007.

Murohara T, Horowitz JR, Silver M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor enhances vascular permeability via nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Circulation. 1998;97:99-107.

Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff N, Plum F. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Post F. Dementia, depression and pseudodementia. In: Benson DF, Blumer D, editors. Psychiatric Aspects of Neurologic Disease. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1975:99-120.

Recht LD, Glantz M. Neoplastic diseases. In: Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2008:2637-2642.

Schmidt B, Czosnyka M, Schwarze JJ, et al. Cerebral vasodilatation causing acute intracranial hypertension: a method for noninvasive assessment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:990-996.

Schrag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guide lines. J Clin Oncol. 1994;2:187-193.

Shapiro WR, Shapiro JR, Walker RW. Central nervous system. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Lichter AS, Niederhuber JE, editors. Clinical Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:1103-1192.

Strugar JG, Criscuolo GR, Rothbart D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth/permeability factor expression in human glioma specimens: correlation with vasogenic brain edema and tumor-associated cysts. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:682-689.

1 Shapiro WR, Shapiro JR, Walker RW. Central nervous system. In: Abeloff MD, Armitage JO, Lichter AS, Niederhuber JE, editors. Clinical Oncology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2000:1103-1192.

2 Darnell RB, Posner JB. Paraneoplastic syndromes affecting the nervous system. Semin Oncol. 2006;33:270-298.

3 Schmidt B, Czosnyka M, Schwarze JJ, et al. Cerebral vasodilatation causing acute intracranial hypertension: a method for noninvasive assessment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1999;19:990-996.

4 Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff N, Plum F. Plum and Posner’s Diagnosis of Stupor and Coma, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

5 Strugar JG, Criscuolo GR, Rothbart D, et al. Vascular endothelial growth/permeability factor expression in human glioma specimens: correlation with vasogenic brain edema and tumor-associated cysts. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:682-689.

6 Murohara T, Horowitz JR, Silver M, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor/vascular permeability factor enhances vascular permeability via nitric oxide and prostacyclin. Circulation. 1998;97:99-107.

7 Post F. Dementia, depression and pseudodementia. In: Benson DF, Blumer D, editors. Psychiatric Aspects of Neurologic Disease. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1975:99-120.

8 Forsyth PA, Posner JB. Headaches in patients with brain tumors: a study of 111 patients. Neurology. 1993;43:1678-1683.

9 Recht LD, Glantz M. Neoplastic diseases. In: Engel J, Pedley TA, editors. Epilepsy: A Comprehensive Textbook. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott: Williams & Wilkins; 2008:2637-2642.

10 Ketz E. Brain tumors and epilepsy. In: Vinken P, Bruyn GW, editors. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing; 1974:254-269.

11 Hughes JR, Zak SM. EEG and clinical changes in patients with chronic seizures associated with slowly growing brain tumors. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:540-543.

12 Moots PL, Maciunas RJ, Eisert DR, et al. The course of seizure disorders in patients with malignant gliomas. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:717-724.

13 Bartolomei JC, Christopher S, Vives K, et al. Low-grade gliomas of chronic epilepsy: a distinct clinical and pathological entity. J Neurooncol. 1997;34:79-84.

14 Gilles FH, Sobel E, Leviton A, et al. Epidemiology of seizures in children with brain tumors. J Neurooncol. 1992;12:53-68.

15 Huber A. Eye Symptoms in Brain Tumors. St. Louis: Mosby; 1971. 86-155

16 Meyers CA, Hess KR, Yung WK, Levin VA. Cognitive function as a predictor of survival in patients with recurrent malignant glioma. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:646-650.

17 Blumer D, Benson DF. Personality changes with frontal and temporal lobe lesions. In: Benson DF, Blumer D, editors. Psychiatric Aspects of Neurologic Disease. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1975:151-170.

18 Cardosa ER, Peterson EW. Pituitary apoplexy: a review. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:363-373.

19 Karnofsky DA, Burchenal J. The clinical evaluation of chemotherapeutic agents in cancer. In: MacLeod CM, editor. Evaluation of Chemotherapeutic Agents. New York: Columbia University Press; 1949:191-205.

20 Schrag CC, Heinrich RL, Ganz PA. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guide lines. J Clin Oncol. 1994;2:187-193.

21 Mor V, Laliberte L, Morris JN, et al. The Karnofsky performance status scale: an examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer. 1984;53:2002-2007.

22 Mackworth N, Fobair P, Prados MD. Quality of life self-reports from 200 brain tumor patients: comparisons with Karnofsky performance scores. J Neurooncol. 1992;14:243-253.

23 Dalmau J, Rosenfeld MR. Paraneoplastic syndromes of the CNS. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:327-340.

24 Gultekin SH, Rosenfeld MR, Voltz R, et al. Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis: neurological symptoms, immunological findings and tumour association in 50 patients. Brain. 2000;123:1481-1494.

25 Bataller L, Graus F, Saiz A, Vilchez JJ. Clinical outcome in adult onset idiopathic or paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus. Brain. 2001;124:437-443.