Chapter 55 Clinical Approach to the Patient With Bleeding or Bruising

Influences on Presenting Problems

1. The nature and severity of the defect, the presence of a single or multiple risk factors for bleeding

2. Whether the bleeding problem is congenital or acquired

3. Antecedent exposures to hemostatic challenges (such as surgery, dental extraction, menses, and childbirth) and the risk for bleeding with each of these challenges

4. The presence of other medical problems (e.g., renal, liver, or thyroid disease), including anemia

5. Variability in the bleeding symptoms experienced by individuals without bleeding problems (e.g., nosebleeds, bruising) and by individuals with known bleeding disorders, even within families with the same defect

6. Local factors (e.g., vascular lesions, diverticular disease, or cancerous lesions in the gastrointestinal tract)

7. Treatments that increase the risk for bleeding (e.g., nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug [NSAID] use for pain control, anticoagulant therapy, etc.)

8. Whether treatments were used to prevent or control bleeding, or if they reduced bleeding when prescribed for other reasons (e.g., reduced menstrual bleeding while on oral contraceptives to prevent pregnancy)

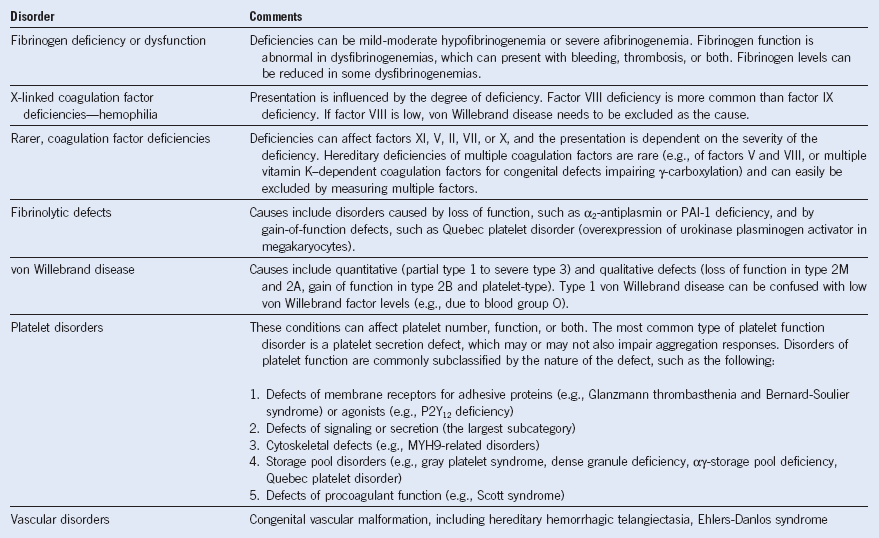

| Major Categories | Comments |

|---|---|

| No bleeding disorder | Symptoms do not reflect a bleeding disorder and have another explanation (e.g., a surgical bleed, not due to a bleeding disorder). |

| Possible bleeding disorder | The laboratory findings are nondiagnostic, and the bleeding history is considered equivocal (e.g., unexplained serious bleed with one surgical procedure; unexplained menorrhagia without other bleeding problems). |

| Definite bleeding disorder, undefined or indeterminate type | The bleeding history is consistent with a bleeding disorder; however, the laboratory findings are nondiagnostic. Commonly the bleeding history resembles mild to moderate defects in platelet function or von Willebrand factor. The diagnosis should only be made once an adequate evaluation for common bleeding disorders (e.g., for von Willebrand disease and platelet aggregation and release defects) is completed. If testing is not complete, the classification should indicate the types of conditions excluded or not excluded, for example: mild mucocutaneous bleeding problem, von Willebrand disease excluded, mild mucocutaneous bleeding problem, platelet release defects not yet excluded. |

| Definite bleeding disorder with a defined cause | The symptoms and laboratory findings are considered diagnostic of a bleeding disorder. Tables 55-2 and 55-3 summarize many of the potential inherited and acquired causes. |

Case 2: Illustration of the Importance of Assessing Both Personal and Familial Bleeding Problems

Table 55-3 Differential Diagnosis of Acquired Bleeding Problems

| Disorder | Comments |

|---|---|

| Drug induced | Aspirin, NSAIDs, other platelet function inhibitors (e.g., P2Y12 and αIIbβ3 inhibitors), anticoagulants, fibrinolytic drugs, and antidepressants are common causes |

| Acquired factor deficiencies | The causes can be immune (e.g., acquired factor VIII deficiency, acquired factor V deficiency) or nonimmune. Reductions in multiple factors can result from vitamin K deficiency, treatment with vitamin K antagonists, liver disease, hemodilution, and rarely snakebites. Severe acquired hypofibrinogenemia is commonly due to a postpartum coagulopathy or severe liver disease. Prothrombin deficiency occurs with some lupus anticoagulants. Amyloidosis can cause an acquired factor X deficiency, which may be associated with reductions in other coagulation factors synthesized in the liver if the liver is involved. |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | The manifestations can include thrombocytopenia, consumption of coagulation factors, including fibrinogen, and impairment of hemostatic mechanisms from the fibrin/fibrinogen degradation products. Causes are wide ranging and include postpartum consumptive states, prostate and other cancers, and snakebites. |

| Acquired von Willebrand disease | The cause can be immune (often in association with an IgG paraprotein) or nonimmune (e.g., increased proteolysis of von Willebrand factor with stenotic aortic valvular disease). |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | Bleeding is usually influenced by the extent of the thrombocytopenia. Some autoantibodies interfere with platelet membrane receptor function, causing bleeding disproportionate to the thrombocytopenia. |

| Non–drug induced, acquired platelet function disorders | The cause can be immune (see earlier) or nonimmune, typically from bone marrow disorders, although secretion defects can be secondary to Cushing syndrome or hypothyroidism. |

| Liver disease | Liver disease can cause thrombocytopenia, deficiencies of coagulation factors, hypofibrinogenemia and dysfibrinogenemia, and increased fibrinolysis. In mild liver disease, factor VII and sometimes factors XI and XII are low. Fibrinogen is often increased in early liver disease, and if low, the finding suggests severe liver disease. |

| Renal disease | Anemia is an important predictor of uremic bleeding. Uremic bleeding is typically associated with severe renal impairment. |

| Hypothyroidism | Hypothyroidism can cause an acquired von Willebrand disease and acquired defects in platelet function. |

| Cushing syndrome | This syndrome should be suspected when there are symptoms and findings suggestive of Cushing syndrome or treatment with systemic or topical glucocorticoids. |

| Surgical bleeding | This is often a diagnosis of exclusion, although the procedural notes sometimes document that a technical problem was encountered that led to abnormal bleeding. |

| Vitamin K deficiency | Newborns are at risk, as are individuals with malabsorption and/or receiving broad-spectrum antibiotics that reduce vitamin K production by reducing gut bacteria. Older adults are also at greater risk for developing vitamin K deficiency, due to reduced stores from poorer intake of vitamin K. If the patient does not respond to parenteral vitamin K, other causes should be considered. |

| Vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) | This diagnosis should be considered when there is lethargy with skin and gum bleeding (perifollicular hemorrhages, gum bleeding with swelling). The condition is rare in developed countries. The cause is usually a very poor diet or malabsorption. |

IgG, Immunoglobulin G; NSAID, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug.

Signs of Active or Recent Bleeding and Conditions Associated With Bleeding

1. Petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages (typical of scurvy)

2. Oral blood blisters, particularly if the patient has thrombocytopenia

3. Ecchymoses, hematomas, and skin pigmentation changes due to recurrent bleeds

4. Signs of active bleeding from a site of trauma or an incision, including excessive blood loss into drains

5. Sequelae of previous bleeds in individuals known or suspected to have a severe bleeding disorder, such as muscle wasting and arthropathy, neurologic abnormalities from prior intracranial or compartment syndrome bleeds

6. Pallor due to anemia: the palms are usually notably pale when the hemoglobin is less than 10 g/dL

7. Signs of an underlying hematologic disorder, such as lymphadenopathy and/or splenomegaly

8. Signs of acute or chronic liver disease, such as jaundice, hepatomegaly, spider nevi, palmar erythema, or Dupuytren contractures

9. Signs of an endocrine disorder, such as hypothyroidism or Cushing syndrome

10. Vascular lesions such as telangiectasia on the face or buccal mucosa, which can suggest hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia

11. Hyperextensibility if the bleeding history suggests Ehlers-Danlos syndrome as a potential diagnosis

12. Signs that suggest a syndromic bleeding disorder (albinism, hearing impairment, absent radii)

The Laboratory Manifestations of Bleeding Disorders

The laboratory manifestations of bleeding disorders can include abnormalities from the following:

1. The underlying hemostatic defect

2. Bleeding complications (e.g., anemia, iron deficiency, a coagulopathy of hemodilution after resuscitation for a massive bleed, development of red cell antibodies after transfusion)

3. False-positive abnormalities (e.g., prolonged activated partial thromboplastin time [aPTT] due to an incidental mild factor XII deficiency that occurs in about 1 of 200 patients or a lupus anticoagulant, which can be a transient finding in about 5% of ill, hospitalized patients)

4. Extremes of normal variation (e.g., mildly low von Willebrand factor levels in an individual who is blood group O, absent secondary aggregation with epinephrine in adjusted platelet rich–plasma aggregation studies).